CLAMANTIS the MALS Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issn 0017-0615 the Gissing Newsletter

ISSN 0017-0615 THE GISSING NEWSLETTER “More than most men am I dependent on sympathy to bring out the best that is in me.” – George Gissing’s Commonplace Book ********************************** Volume XIX, Number 4 October, 1983 ********************************** -- 1 -- Gissing, Grant Allen and “Free Union” Alison Cotes University of Queensland At the end of Gissing’s novel of 1893, The Odd Women, Rhoda Nunn finally shows herself unwilling, in spite of her devotion to the feminist cause, to defy convention totally and enter into a free union with Everard Barfoot. On these grounds, Everard decides against forming a permanent relationship with her, and sums her up in these words: He had magnified Rhoda’s image. She was not the glorious rebel he had pictured. Like any other woman, she mistrusted her love without the sanction of society … He had not found his ************************************************* Editorial Board Pierre Coustillas, Editor, University of Lille Shigeru Koike, Tokyo Metropolitan University Jacob Korg, University of Washington, Seattle Editorial correspondence should be sent to the Editor: 10, rue Gay-Lussac, 59110-La Madeleine, France, and all other correspondence to C. C. KOHLER, 12, Horsham Road, Dorking, Surrey, RH4 2JL, England. Subscriptions: Private Subscribers: £3.00 per annum Libraries: £5.00 per annum ************************************************* -- 2 -- ideal – though in these days it assuredly existed.1 Everard’s ideal woman, brave enough to live out her rebellion against the convention of marriage while retaining her moral integrity, had hardly been the subject of serious English fiction before this date. Sally Mitchell2 mentions a number of novels of the mid-Victorian period where heroines of this kind occur, notably Matilda Charlotte Houstoun’s Recommended to Mercy, but they are for the most part novels of minor literary substance and even less influence. -

Document Resume Ed 128 802 Cs 202 916 Tttle

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 128 802 CS 202 916 TTTLE Associated Writing Programs. 1975 Catalogue of Programs. INSTITUTION Associated Writing Programs. SPONS AGENCY National Endowment for the Arts, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 46p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$2.06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Bachelors Degrees; Catalogs; *College Programs; *Creative Writing; Directories; *Graduate Study; Higher Education; Masters Degrees; Program Descriptions; *Undergraduate Study IDENTIFIERS *Associated Writing Programs ABSTRACT This catalogue provides full information on most graduate degree programs in writing in the United States,with additional information on a number of undergraduate programs. In addition, the various functions and services of the Associated Writing Programs (AWP) are described. Two short sections, "Creative Writing at an Urban Campus," and "The M.F.A. and the University," examine, respectively, the innovation of an undergraduate writing program at the Virginia Commonwealth University andthe origins and implications of the Master of Fine Arts degree. (KS) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERICmakes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless,items of marginal * r :lucibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * c microfiche and hardcopy reproductions EPIC makes available * vicl the EPIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS) .EDRS is not * responsible for the quality -

The Brooklyn College Foundation Annual Report 2010 - 2011 2010 – 2011 Annual Report | 1

THE BROOKLYN COLLEGE FOUNDATION Annual Report 2010 - 2011 DEAR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS, The fiscal year ending June 30, 2011, was one of solid growth for the Brooklyn College Foundation. The number of contributions from alumni and friends continued to rise and the total value of gifts and pledges nearly doubled over the previous year. I am pleased to report that we are making considerable progress toward the $200 million goal of our Foundation for Success Campaign. Although the amount raised is impressive, the impact of these donations is what counts. Through the generosity of friends, alumni and private foundations, we were able to grant over 1,200 scholarships and awards. We have provided funding for students to take advantage of unique learning opportunities from New Orleans to Peru, from Paris to South Africa and, of course, right here in Brooklyn. And we have supported new facilities and equipment necessary to provide students with a 21st century education of the highest quality. As chair of the foundation, I am grateful to my fellow trustees for their engagement and leadership. The continuing impact of the foundation is due in large part to their strategic counsel and dedication. I am also grateful for the privilege to work alongside President Karen L. Gould. Under her leadership, Brooklyn College has charted an ambitious and exciting vision for the future with student success at its core. On behalf of the trustees and staff of the Brooklyn College Foundation, I want to thank everyone who has contributed to our mission to provide access to excellence for the students of this great institution. -

Israeli Literature and the American Reader

Israeli Literature and the American Reader by ALAN MINTZ A HE PAST 25 YEARS HAVE BEEN a heady time for lovers of Is- raeli literature. In the 1960s the Israeli literary scene began to explode, especially in terms of fiction. Until then, poetry had been at the center of literary activity. While S.Y. Agnon's eminence, rooted in a different place and time, persisted, the native-born writers who began to produce stories and novels after 1948 never seemed to be able to carry their ef- forts much beyond the struggles and controversies of the hour. Then suddenly there were the short stories of Amos Oz, A.B. Yehoshua, Aharon Appelfeld, and Amalia Kahana-Carmon, followed by their first and second novels. These writers were soon joined by Shulamit Hareven, Yehoshua Kenaz, Yaakov Shabtai, and David Grossman. Into the 1980s and 1990s the debuts of impressive new writers became more frequent, while the productivity of the by-now established ones only intensified. What was different about this new Israeli literature was the quality and inventiveness of its fictional techniques and its ability to explore univer- sal issues in the context of Israeli society. There was also a new audience for this literature; children of immigrants had become sophisticated He- brew readers. Many of the best books became not only critical successes but best-sellers as well. Was this a party to which outsiders were invited? Very few American Jews knew Hebrew well enough to read a serious modern Hebrew book, so that even if they were aware of the celebration, they could not hear the music. -

Milton Hindus Papers03.Mwalb00136a

Milton Hindus papers03.MWalB00136A This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 30, 2021. eng Describing Archives: A Content Standard Brandeis University 415 South St. Waltham, MA URL: https://findingaids.brandeis.edu/ Milton Hindus papers03.MWalB00136A Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 4 Other Descriptive Information ....................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Personal and Academic Papers ................................................................................................................... 5 Correspondence .......................................................................................................................................... 10 Published Articles ..................................................................................................................................... -

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels

Table of Contents Acknowledgments Alan Lelchuck Introduction Bibliographic Note Uri Nissan Gnessin Chapter one Chapter two Chapter three Yosef Haim Brenner Chapter one Chapter two Chapter three Chapter four Chapter five Chapter six Chapter seven Chapter eight Chapter nine Chapter ten Yitzhak Shami Chapter one Chapter two Chapter three Chapter four Chapter five Chapter six Chapter seven Chapter eight Chapter nine Chapter ten S.Y. Agnon Chapter one David Fogel Chapter one Amos Oz Chapter one Chapter two Chapter three Chapter four Chapter five Chapter six Chapter seven Chapter eight Chapter nine Chapter ten Chapter eleven Chapter twelve Chapter thirteen Yehoshua Kenaz Chapter one A.B. Yehoshua Chapter one About the Editors Eight Great Hebrew Short Novels EDITED BY Alan Lelchuk and Gershon Shaked WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY Alan Lelchuk The Toby Press The Toby Press Third Revised Edition, 2009 The Toby Press llc POB 8531, New Milford, CT 06776-8531, USA & POB 2455, London W1A 5WY, England www.tobypress.com Copyright © 1983 by Alan Lelchuk and Gershon Shaked Introduction Copyright © 1983 by Alan Lelchuk The Toby Press thanks The Institute for the Translation of Hebrew Literature for their kind assistance in the preparation of this revised edition. All translations are © The Institute for the Translation of Hebrew Literature, except as noted below. SIDEWAYS, by Uri Nissan Gnessin. First published in Hebrew in ha-Z’man, 1905. English translation by Hillel Halkin, copyright © 1983 NERVES, by Yosef Haim Brenner. First published in Hebrew in Shalekhet, Revivim, 1910–11. English translation by Hillel Halkin, copyright © 1983 THE VENGEANCE OF THE FATHERS, by Yitzhak Shami. -

Winter 2004 Iraqi Fulbrighters Now in U.S

The Fulbrighters' Fulbright AT 'I tt A SSOCIATION ..Ly ews1,e er Celebrating 27 Years of Service to the Fulbright Program, 1977 2004 Volume XXV, No. 1 Winter 2004 Iraqi Fulbrighters Now in U.S. We're Back! Fulbright Program Reestablished in Iraq The Fulbrighters 'Newsletter Resumes Publication Thanks to Fulbright Association members who let us kr,ow they missed reading The Fulbrighters' Newsletter last year. Although we published the special edition of the newsletter on the 2003 Fulbright Prize, production of the regular _ 1..• ..1. ..-.. newsletter was suspended while we Secretary of State Colin Powell with Iraqi Fulbrighters at a Feb. 2 meeting in devoted resources to implementing Washington, D.C. U.S. Department of State Photo by Michael Gross. our new online community and directory and our enhanced web site The U.S. Department of State has Fulbrighters will participate in at www.fulbright.org. reestablished the Fulbright program special pre-academic training For an overview of the with Iraq following a 14-year programs at Indiana University, membership benefits offered through suspension. The first group oflraqi University of Arizona, University the online community, please see the Fulbrighters, 23 students and two of California-Santa Cruz, and articles on pages four and nine. We scholars , arrived in the U.S . on Feb. University of Oregon to refine their hope that you enjoy this issue of the 1. The group participated in a English language skills, to learn newsletter, and we invite you to send week-long orientation in about the United States, its society, information for publication in future Washington, D.C., meeting with values, and institutions, and to be editions. -

Papers of Philip Roth

Philip Roth A Register of His Papers in the Library of Congress Prepared by Michael Spangler with the assistance of Chanté Wilson Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2005 Contact information: http://lcweb.loc.gov/rr/mss/address.html Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2006 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms006030 Latest revision: 2007 June Collection Summary Title: Papers of Philip Roth Span Dates: 1938-2001 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1960-1999) ID No.: MSS22491 Creator: Roth, Philip, 1933- Extent: 25,000 items; 294 containers plus 5 oversize; 122.6 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Author. Correspondence, drafts, galleys, notes, interviews, play scripts, clippings, and photographs documenting Roth's literary career. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. Names: Roth, Philip Aiken, Joan, 1924-2004--Correspondence Ames, Elizabeth--Correspondence Asher, Aaron--Correspondence Atlas, James--Correspondence Baker, R. S. (Robert Samuel), 1926-2004--Correspondence Bellow, Saul--Correspondence Bloom, Claire, 1931- --Correspondence Brookner, Anita--Correspondence Brustein, Robert Sanford, 1927- --Correspondence Carter, Angela, 1940- --Correspondence Cassill, R. V. (Ronald -

![Philip Roth Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3536/philip-roth-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-rendered-8323536.webp)

Philip Roth Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered

Philip Roth Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2013 Revised 2013 March Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms006030 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm82022491 Prepared by Michael Spangler with the assistance of Chanté Wilson Collection Summary Title: Philip Roth Papers Span Dates: 1938-2001 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1960-1999) ID No.: MSS22491 Creator: Roth, Philip, 1933- Extent: 25,000 items ; 255 containers plus 5 oversize ; 107 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Author. Correspondence, drafts, galleys, notes, interviews, play scripts, clippings, and photographs documenting Roth's literary career. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Aiken, Joan, 1924-2004--Correspondence. Ames, Elizabeth--Correspondence. Asher, Aaron--Correspondence. Atlas, James--Correspondence. Baker, R. S. (Robert Samuel), 1926-2004--Correspondence. Bellow, Saul--Correspondence. Bloom, Claire, 1931- --Correspondence. Brookner, Anita--Correspondence. Brustein, Robert Sanford, 1927- --Correspondence. Carter, Angela, 1940-1992--Correspondence. Cassill, R. V. (Ronald Verlin), 1919-2002--Correspondence. Clark, Blair, 1917-2000--Correspondence. Conarroe, Joel, 1934- --Correspondence. Crichton, Robert--Correspondence. Dayan, Yaël, 1939- --Correspondence. Donadio, Candida, 1929-2001--Correspondence. Dunford, Judith--Correspondence. Engle, Paul, 1908-1991--Correspondence. Fuller, Blair--Correspondence. Geng, Veronica--Correspondence. -

Unclean Lips: Obscenity and Jews in American Literature

Unclean Lips: Obscenity and Jews in American Literature by Joshua N. Lambert A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in The University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Professor Jonathan E. Freedman, Co-Chair Professor Anita Norich, Co-Chair Professor June M. Howard Professor Deborah Dash Moore Associate Professor Julian A. Levinson Copyright © Joshua N. Lambert 2009 Acknowledgments This project benefited from generous fellowships from the Rackham Graduate School and the Frankel Center for Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan, as well as the Center for Jewish History in New York City, the Feinstein Center for American Jewish History at Temple University, and the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture. My research trips to archives in Washington, D.C., New York, and Toronto were made possible by a grant from the Van Akin and Julia Burd Fund for Research in English at the University of Michigan. Many scholars have mentored or advised me over the years, and I am grateful to them. In addition to introducing me to the study of modern Jewish literature during my undergraduate years at Harvard, Ruth Wisse suggested that I consider the University of Michigan as an institution unusually well-equipped to support the study of Jewish literature within an English department. I also profited, in the years between college and graduate school, from the guidance of Steven Zipperstein and Maxine Rodburg. When I arrived in Ann Arbor, I discovered a remarkable group of advisors whose approaches to pedagogy and scholarship have inspired me. -

Barbara Kreiger and the Nature of Here

RSA19_009.qxd 12-05-2010 17:35 Pagina 183 RSA Journal 19/2008 ELÈNA MORTARA Barbara Kreiger and the Nature of Here It is a pleasure for me to introduce an unpublished text by Barbara Kreiger in the Journal of the Italian Association of North American Studies. Barbara Kreiger is a New Englander by birth, who was raised in Connecticut, received her Ph.D. in English and American Literature from Brandeis University in 1978 (where I first met her one year later) and soon after moved to New Hampshire with her husband, novelist Alan Lelchuk. Since 1982 she has taught literary nonfiction and creative writing at Dartmouth College, in the English Department and in the Master of Arts in Liberal Studies program, where she is Chair of the M.A.L.S. Creative Writing Concentration. She is the author of The Dead Sea: Myth, History, and Politics (1997, first published in 1988 as Living Waters; “a rare natural, political, and human history … Remarkable and timely.” – Booklist) and Divine Expectations: An American Woman in 19th-Century Palestine (1999; the little- known story of an American Christian pioneer in Palestine, woven “into the larger context of the region and its history,” and written with “the deft touch of a novelist”). A Distinguished Lecturer Award from Dartmouth College enabled her to travel to Jerusalem and Jaffo one more time before the latter book was in print. In 2004 she received a Fulbright Award and spent the 2004-2005 academic year in Rome, where she taught literary non- fiction (including memoir, travel and the personal essay) to graduate stu- dents in English at the University of Rome “Tor Vergata.” Since then she has returned, upon my invitation, to “Tor Vergata” as a Visiting Professor to pursue her research on memory and place, and accomplish her own non- fiction creative writing project. -

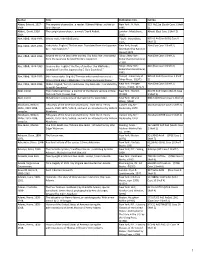

PRPL Master List 6-7-21

Author Title Publication Info. Call No. Abbey, Edward, 1927- The serpents of paradise : a reader / Edward Abbey ; edited by New York : H. Holt, 813 Ab12se (South Case 1 Shelf 1989. John Macrae. 1995. 2) Abbott, David, 1938- The upright piano player : a novel / David Abbott. London : MacLehose, Abbott (East Case 1 Shelf 2) 2014. 2010. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Warau tsuki / Abe Kōbō [cho]. Tōkyō : Shinchōsha, 895.63 Ab32wa(STGE Case 6 1975. Shelf 5) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Hakootoko. English;"The box man. Translated from the Japanese New York, Knopf; Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) by E. Dale Saunders." [distributed by Random House] 1974. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Beyond the curve (and other stories) / by Kobo Abe ; translated Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Kodansha International, c1990. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Tanin no kao. English;"The face of another / by Kōbō Abe ; Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) [translated from the Japanese by E. Dale Saunders]." Kodansha International, 1992. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Bō ni natta otoko. English;"The man who turned into a stick : [Tokyo] : University of 895.62 Ab33 (East Case 1 Shelf three related plays / Kōbō Abe ; translated by Donald Keene." Tokyo Press, ©1975. 2) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Mikkai. English;"Secret rendezvous / by Kōbō Abe ; translated by New York : Perigee Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) Juliet W. Carpenter." Books, [1980], ©1979. Abel, Lionel. The intellectual follies : a memoir of the literary venture in New New York : Norton, 801.95 Ab34 Aa1in (South Case York and Paris / Lionel Abel.