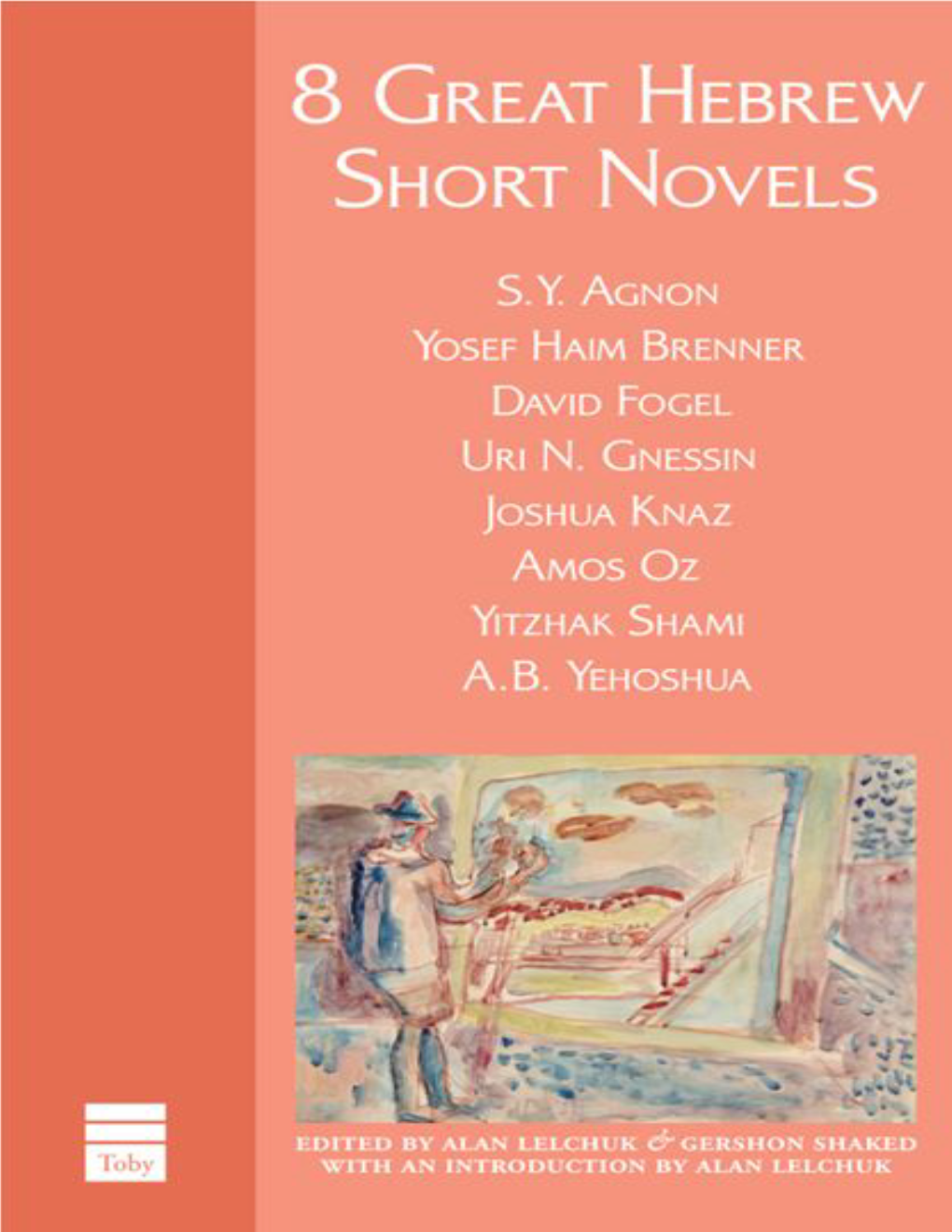

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Around the Point

Around the Point Around the Point: Studies in Jewish Literature and Culture in Multiple Languages Edited by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman and Ber Kotlerman Around the Point: Studies in Jewish Literature and Culture in Multiple Languages, Edited by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman and Ber Kotlerman This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman, Ber Kotlerman and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5577-4, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5577-8 CONTENTS Preface ...................................................................................................... viii Around the Point .......................................................................................... 1 Hillel Weiss Medieval Languages and Literatures in Italy and Spain: Functions and Interactions in a Multilingual Society and the Role of Hebrew and Jewish Literatures ............................................................................... 17 Arie Schippers The Ashkenazim—East vs. West: An Invitation to a Mental-Stylistic Discussion of the Modern Hebrew Literature ........................................... -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

This Year in Jerusalem: Israel and the Literary Quest for Jewish Authenticity

This Year in Jerusalem: Israel and the Literary Quest for Jewish Authenticity The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hoffman, Ari. 2016. This Year in Jerusalem: Israel and the Literary Quest for Jewish Authenticity. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33840682 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA This Year in Jerusalem: Israel and the Literary Quest for Jewish Authenticity A dissertation presented By Ari R. Hoffman To The Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the subject of English Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 15, 2016 © 2016 Ari R. Hoffman All rights reserved. ! """! Ari Hoffman Dissertation Advisor: Professor Elisa New Professor Amanda Claybaugh This Year in Jerusalem: Israel and the Literary Quest for Jewish Authenticity This dissertation investigates how Israel is imagined as a literary space and setting in contemporary literature. Israel is a specific place with delineated borders, and is also networked to a whole galaxy of conversations where authenticity plays a crucial role. Israel generates authenticity in uniquely powerful ways because of its location at the nexus of the imagined and the concrete. While much attention has been paid to Israel as a political and ethnographic/ demographic subject, its appearance on the map of literary spaces has been less thoroughly considered. -

Comparative Literary Studies Program Course Descriptions 2013-2014

Comparative Literary Studies Program Course Descriptions 2013-2014 Fall 2013 CLS 206: Literature and Media: LaByrinths Lectures: TTh 11:00-12:20, Fisk B17 Instructor: Domietta Torlasco Expected Enrollment: Course Description: This course will trace a brief history of labyrinths through literature, architecture, cinema, and new media. From classical mythology to cutting-edge computer games, the figure of the labyrinth has shaped the way in which we ask crucial questions about space, time, perception, and technology. Whether an actual maze or a book or a film, the labyrinth presents us with an entanglement of lines and pathways that is as demanding as it is engrossing and even exhilarating. As we move from medium to medium, or pause in between media, the labyrinth will in turn emerge as an archetypal image, a concrete pattern, a narrative structure, a figure of thought, a mode of experience....Among the works which we will analyze are Jorge Luis Borges' celebrated short stories, Italo Calvino's experiments in detective fiction, Mark Z. Danielewski' hyper- textual novelHouse of Leaves, films such as Orson Welles' Citizen Kane (1941), Stanley Kubrick's The Shining (1980), and Christopher Nolan's Inception (2010), and the more intellectually adventurous video games. Evaluation Method: 1. Attendance and participation to lectures AND discussion sessions (25% of the final grade). Please note that more than three absences will automatically reduce your final grade. 2. Two short response papers (15%). 3. Mid-term exam (25%). 4. Final 5-6 page paper (35%). CLS 211 / ENG 211:Topics in Genre: Intro to Poetry Lectures: MW 11:00-11:50, Harris 107 Discussion Sections: F 11:00, 1:00 Instructor: Susannah Gottlieb Expected Enrollment: 100 Course Description: The experience of poetry can be understood in it at least two radically different ways: as a raw encounter with something unfamiliar or as a methodically constructed mode of access to the unknown. -

The Desert Away from Home: Amos Oz's Memoir, Levinasian Ethics, and Binaries of Pain in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

ELOHI Peuples indigènes et environnement 8 | 2015 Exodes, déplacements, déracinements The Desert Away from Home: Amos Oz’s Memoir, Levinasian Ethics, and Binaries of Pain in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Orit Rabkin Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/elohi/939 DOI: 10.4000/elohi.939 ISSN: 2268-5243 Publisher Presses universitaires de Bordeaux Printed version Date of publication: 1 July 2015 ISBN: 979-10-300-0130-3 ISSN: 2431-8175 Electronic reference Orit Rabkin, « The Desert Away from Home: Amos Oz’s Memoir, Levinasian Ethics, and Binaries of Pain in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict », ELOHI [Online], 8 | 2015, Online since 01 July 2015, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/elohi/939 ; DOI : 10.4000/elohi.939 © PUB-CLIMAS The Desert Away from Home: Amos Oz’s Memoir, Levinasian Ethics, and Binaries of Pain in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict ORIT RABKIN Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva (Israel) Writing a memoir describing the early days of the Zionist state hardly seems exceptional, yet Amos Oz’s A Tale of Love and Darkness (2004) achieves excep- tionality. Oz achieves what most Israelis, including myself, struggle with. On the one hand, he shares with his readers his Jewish family’s persecution in the Eastern European Diaspora followed by an insider’s, sympathetic description of the Zionist project of rebuilding the ancient homeland. On the other hand, he deeply feels the pain of those others whom, as an Israeli Jew, I can see are still reeling from our return. Oz creates a narrative space that acknowledges Jew- ish presence without needing to simultaneously preclude Arab claims (all the while focusing on his family and his people). -

June 8, 2014 Biographies of Honorary Doctorate Recipients GAIL ASPER

Hebrew University of Jerusalem Convocation Ceremony: June 8, 2014 Biographies of Honorary Doctorate Recipients GAIL ASPER OC OM A community leader and role model, Gail Asper continues to work tirelessly to enhance the world in which she lives. As President and a Trustee of the Asper Foundation, she is a driving force behind projects in Canada and Israel and spearheaded the creation of the Canadian Museum of Human Rights in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Her commitment to the Hebrew University ranges from serving on the Board of Governors to being a member of the Canadian Friends National Board. The Asper Centre for Entrepreneurship at the School of Business Administration continues to flourish thanks to the support of the Asper Foundation; in addition Gail is passionate about student support, the Rothberg International School and the Institute for Medical Research Israel-Canada. Gail received her law degree from the University of Manitoba in 1984, and joined Canwest Global Communications Corporation as General Counsel and Corporate Secretary in 1989, a position she held until 2008. She is currently President of the Canwest Foundation. Today Gail’s community involvement includes numerous positions to which she brings her passion and dedication. Daughter of the late Izzy Asper, she realized his dream to build the Canadian Museum of Human Rights, serving as a member of its inaugural Board and as Chair of its National Campaign. She is Director Emerita of the Centre for Cultural Management at the University of Waterloo and is a past Chair of the Board of Directors of the United Way of Winnipeg. Gail has also served on many boards within the Winnipeg Jewish Community. -

A Tribute to Amos Oz Z”L Parashat Va'era January 5, 2019; 28 Tevet

A Tribute to Amos Oz z”l Parashat Va’era January 5, 2019; 28 Tevet 5779 Rabbi Adam J. Raskin, Congregation Har Shalom I am completely intimidated by the thought of sitting down to a cup of Turkish coffee and conversation with Amos Oz. While I have such profound respect and admiration for Israel’s towering author-laureate who died just this past Friday, there is something about him that sort-of terrifies me. First of all, Amos Oz was a Hebrew language elitist…He once announced in a public discussion with British Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks that “there is no difference between the castration of the Hebrew language by the Orthodox, the Reform, or the Conservative movement. They represent a unified front.” Oz felt that Hebrew was the one and only common denominator among Jews from all over the world, and all different religious and cultural pursuasions. And he was deeply dismayed by the relatively poor quality of the Hebrew language, even as spoken today in the modern State of Israel. I am sure that he would not approve of my conversational but less than fluent Hebrew. Oz was also an ardent secular Jew. He rejected ideas of promised land, or messianism, or destiny, or mission, or miracle. He once said about his fellow Israelis: “We are six and a half million citizens, six and a half million prime ministers, six and a half million prophets, six and a half million Messiahs, and everyone shouts at the same time and no one listens. Only I sometimes listen, [and] that is how I make a living.” So why am I mourning for a high-brow Hebraist who rejected the fundamental tenets of my faith, who once declared “I cannot use such words as ‘the promised land’ or the ‘promised borders’ because I do not believe in the one who made the promise?” Why do I feel that the State of Israel and the Jewish people have suffered a profound loss with the death of Amos Oz? Well, let me tell you… Amos Klausner was born in Jerusalem, 9 years before David Ben Gurion declared the establishment of the State of Israel. -

Engendering Relationship Between Jew and America

Oedipus' Sister: Narrating Gender and Nation in the Early Novels of Israeli Women by Hadar Makov-Hasson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies New York University September, 2009 ___________________________ Yael S. Feldman UMI Number: 3380280 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3380280 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 © Hadar Makov-Hasson All Rights Reserved, 2009 DEDICATION בדמי ימיה מתה אמי , וכבת ששים שש שנה הייתה במותה This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of my mother Nira Makov. Her love, intellectual curiosity, and courage are engraved on my heart forever. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would have never been written without the help and support of several people to whom I am extremely grateful. First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Professor Yael Feldman, whose pioneering work on the foremothers of Hebrew literature inspired me to pursue the questions that this dissertation explores. Professor Feldman‘s insights illuminated the subject of Israeli women writers for me; her guidance and advice have left an indelible imprint on my thinking, and on this dissertation. -

New Yiddish Library the New Yiddish Library Is a Joint Project of the Fund for the Translation of Jewish Literature and the National Yiddish Book Center

New Yiddish Library The New Yiddish Library is a joint project of the Fund for the Translation of Jewish Literature and the National Yiddish Book Center. Additional support comes from The Kaplen Foundation, the Felix Posen Fund for the Translation of Modern Yiddish Literature, and Ben and Sarah Torchinsky. david g. roskies, series editor The Zelmenyaners: A Family moyshe kulbak Saga translated by hillel halkin introduction and notes by sasha senderovich new haven and london Copyright ∫ 2013 by the Fund for the Translation of Jewish Literature and the National Yiddish Book Center. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. o≈ce) or [email protected] (U.K. o≈ce). Set in Scala type by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kulbak, Moshe, 1896–1940. [Zelmenyaner. English] The Zelmenyaners : a family saga / Moyshe Kulbak ; translated by Hillel Halkin ; introduction and notes by Sasha Senderovich. p. cm. — (The new Yiddish library) Includes bibliographical references. isbn 978-0-300-11232-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Jewish families—Belarus—Minsk—Fiction. 2. Jews—Belarus— Minsk—Social life and customs—Fiction. 3. Minsk (Belarus)—Fiction. 4. -

שירים נבחרים Yehuda Halevi Hillel Halkin

IJIJIJIJIJIJ יהודה ה�וי שירים נבחרים AD THE SELECTED POEMS OF Yehuda Halevi AD TRANSLATED & ANNOTATED BY Hillel Halkin IJIJIJIJIJIJ IJIJIJIJIJIJ Copyright © 2011 by Hillel Halkin. All rights reserved. Published by Nextbook, Inc., a not-for-profit project devoted to the promotion of Jewish literature, culture, and ideas. This material may not be copied without crediting the translator and the publisher. nextbookpress.com ISBN: 978-0-615-43367-7 Designed and composed by Scott-Martin Kosofsky, at The Philidor Company, Lexington, Massachusetts. philidor.com A note on the typefaces appears on the last page. IJIJIJIJIJIJ IJIJIJIJIJIJIJIJIJIJIJIJIJIJIJIJIJIJIJIJIJI Click on pages or titles for quick links to the pages. iv Foreword by Jonathan Rosen Table of Contents v Introduction by Hillel Halkin רשימת השירים 1 The Poet Thanks an Admirer for a Jug of Wine בך אעיר זמרות 2 To Moshe ibn Ezra, on His Leaving Andalusia איך אחריך אמצאה מרגוע 3 4 To Yitzhak ibn el-Yatom Carved on a Tombstone הידעו הדמעות מי שפכם ארץ כילדה היתה יונקת 5 6 A Wedding Poem Ofra עפרה עזוב לראות אשר יהיה והיה 7 Love’s War לקראת חלל חשקך קרב החזיקי 8 Why, My Darling, Have You Barred All News? מה לך צביה תמנעי ציריך 9 10 On the Death of Yehuda ibn Ezra A Lament for Moshe ibn Ezra ידענוך נדד מימי עלומים ראה זמן כי האנוש הבל 11 12 On the Death of a Daughter Lord, Where Will I Find You? יה אנה אמצאך הה בתי השכחת משכנך 13 14 The Dream Nishmat יחידה שחרי האל וספיו נמת ונרדמת 15 16 Barkhu Ge’ula יעבר עלי רצונך יעירוני בשמך רעיוני 17 18 Ahava Waked By My Thoughts יעירוני רעיוני יעלת -

The Bereaved Father and His Dead Son in the Works of A. B. Yehoshua

The Bereaved Father and His Dead Son in the Works of A. B. Yehoshua Adia Mendelson-Maoz Jewish Social Studies, Volume 17, Number 1, Fall 2010 (New Series), pp. 116-140 (Article) Published by Indiana University Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jss/summary/v017/17.1.mendelson-maoz.html Access provided by The Ohio State University (7 Jan 2014 18:42 GMT) The Bereaved Father and His Dead Son in the Works of A. B. Yehoshua Adia Mendelson-Maoz ABSTRACT In recent years, A. B. Yehoshua has been taken to task for tempering his criticism of Israeli politics and shifting closer to the political center. In this article, I shift the dis- cussion to a historical and poetic perspective through an interpretive evaluation of the bereaved father figure in Yehoshua’s oeuvre. His approach to the bereaved father has undergone a radical transformation. This is clearly seen in his latest works in which he has made the transition from a critical stance toward the bereaved father—one of the most potent images of Zionist ideology—to a more moderate position reflecting internalization and acceptance of bereavement. To investigate this development, I explore the use of the bereavement myth in several of Yehoshua’s works and offer a de- tailed comparison of his early novella Bi-techilat kayits 1970 (Early in the Summer of 1970; 1972) and his more recent work Esh yedidutit (Friendly Fire: A Duet; 2007). Key words: A. B. Yehoshua, Akedah, Hebrew literature n 1992, during a conference on A. B. -

University of London Thesis

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree Year Name of Author C£VJ*r’Nr^'f ^ COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOAN Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the University Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: The Theses Section, University of London Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the University of London Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The University Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962- 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. This thesis comes within category D.