Reading Oz with Kashua

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M E O R O T a Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (Formerly Edah Journal)

M e o r o t A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly Edah Journal) Tishrei 5770 Special Edition on Modern Orthodox Education CONTENTS Editor’s Introduction to Special Tishrei 5770 Edition Nathaniel Helfgot SYMPOSIUM On Modern Orthodox Day School Education Scot A. Berman, Todd Berman, Shlomo (Myles) Brody, Yitzchak Etshalom,Yoel Finkelman, David Flatto Zvi Grumet, Naftali Harcsztark, Rivka Kahan, Miriam Reisler, Jeremy Savitsky ARTICLES What Should a Yeshiva High School Graduate Know, Value and Be Able to Do? Moshe Sokolow Responses by Jack Bieler, Yaakov Blau, Erica Brown, Aaron Frank, Mark Gottlieb The Economics of Jewish Education The Tuition Hole: How We Dug It and How to Begin Digging Out of It Allen Friedman The Economic Crisis and Jewish Education Saul Zucker Striving for Cognitive Excellence Jack Nahmod To Teach Tsni’ut with Tsni’ut Meorot 7:2 Tishrei 5770 Tamar Biala A Publication of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah REVIEW ESSAY Rabbinical School © 2009 Life Values and Intimacy Education: Health Education for the Jewish School, Yocheved Debow and Anna Woloski-Wruble, eds. Jeffrey Kobrin STATEMENT OF PURPOSE Meorot: A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly The Edah Journal) Statement of Purpose Meorot is a forum for discussion of Orthodox Judaism’s engagement with modernity, published by Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School. It is the conviction of Meorot that this discourse is vital to nurturing the spiritual and religious experiences of Modern Orthodox Jews. Committed to the norms of halakhah and Torah, Meorot is dedicated -

Around the Point

Around the Point Around the Point: Studies in Jewish Literature and Culture in Multiple Languages Edited by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman and Ber Kotlerman Around the Point: Studies in Jewish Literature and Culture in Multiple Languages, Edited by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman and Ber Kotlerman This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman, Ber Kotlerman and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5577-4, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5577-8 CONTENTS Preface ...................................................................................................... viii Around the Point .......................................................................................... 1 Hillel Weiss Medieval Languages and Literatures in Italy and Spain: Functions and Interactions in a Multilingual Society and the Role of Hebrew and Jewish Literatures ............................................................................... 17 Arie Schippers The Ashkenazim—East vs. West: An Invitation to a Mental-Stylistic Discussion of the Modern Hebrew Literature ........................................... -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

Comparative Literary Studies Program Course Descriptions 2013-2014

Comparative Literary Studies Program Course Descriptions 2013-2014 Fall 2013 CLS 206: Literature and Media: LaByrinths Lectures: TTh 11:00-12:20, Fisk B17 Instructor: Domietta Torlasco Expected Enrollment: Course Description: This course will trace a brief history of labyrinths through literature, architecture, cinema, and new media. From classical mythology to cutting-edge computer games, the figure of the labyrinth has shaped the way in which we ask crucial questions about space, time, perception, and technology. Whether an actual maze or a book or a film, the labyrinth presents us with an entanglement of lines and pathways that is as demanding as it is engrossing and even exhilarating. As we move from medium to medium, or pause in between media, the labyrinth will in turn emerge as an archetypal image, a concrete pattern, a narrative structure, a figure of thought, a mode of experience....Among the works which we will analyze are Jorge Luis Borges' celebrated short stories, Italo Calvino's experiments in detective fiction, Mark Z. Danielewski' hyper- textual novelHouse of Leaves, films such as Orson Welles' Citizen Kane (1941), Stanley Kubrick's The Shining (1980), and Christopher Nolan's Inception (2010), and the more intellectually adventurous video games. Evaluation Method: 1. Attendance and participation to lectures AND discussion sessions (25% of the final grade). Please note that more than three absences will automatically reduce your final grade. 2. Two short response papers (15%). 3. Mid-term exam (25%). 4. Final 5-6 page paper (35%). CLS 211 / ENG 211:Topics in Genre: Intro to Poetry Lectures: MW 11:00-11:50, Harris 107 Discussion Sections: F 11:00, 1:00 Instructor: Susannah Gottlieb Expected Enrollment: 100 Course Description: The experience of poetry can be understood in it at least two radically different ways: as a raw encounter with something unfamiliar or as a methodically constructed mode of access to the unknown. -

The Desert Away from Home: Amos Oz's Memoir, Levinasian Ethics, and Binaries of Pain in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

ELOHI Peuples indigènes et environnement 8 | 2015 Exodes, déplacements, déracinements The Desert Away from Home: Amos Oz’s Memoir, Levinasian Ethics, and Binaries of Pain in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Orit Rabkin Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/elohi/939 DOI: 10.4000/elohi.939 ISSN: 2268-5243 Publisher Presses universitaires de Bordeaux Printed version Date of publication: 1 July 2015 ISBN: 979-10-300-0130-3 ISSN: 2431-8175 Electronic reference Orit Rabkin, « The Desert Away from Home: Amos Oz’s Memoir, Levinasian Ethics, and Binaries of Pain in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict », ELOHI [Online], 8 | 2015, Online since 01 July 2015, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/elohi/939 ; DOI : 10.4000/elohi.939 © PUB-CLIMAS The Desert Away from Home: Amos Oz’s Memoir, Levinasian Ethics, and Binaries of Pain in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict ORIT RABKIN Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva (Israel) Writing a memoir describing the early days of the Zionist state hardly seems exceptional, yet Amos Oz’s A Tale of Love and Darkness (2004) achieves excep- tionality. Oz achieves what most Israelis, including myself, struggle with. On the one hand, he shares with his readers his Jewish family’s persecution in the Eastern European Diaspora followed by an insider’s, sympathetic description of the Zionist project of rebuilding the ancient homeland. On the other hand, he deeply feels the pain of those others whom, as an Israeli Jew, I can see are still reeling from our return. Oz creates a narrative space that acknowledges Jew- ish presence without needing to simultaneously preclude Arab claims (all the while focusing on his family and his people). -

The Rebbe and the Yak

Hillel Halkin on King James: The Harold Bloom Version JEWISH REVIEW Volume 2, Number 3 Fall 2011 $6.95 OF BOOKS Alan Mintz The Rebbe and the Yak Ruth R. Wisse Yehudah Mirsky Adam Kirsch Moshe Halbertal The Faith of Reds On Law & Forgiveness Yehuda Amital Elli Fischer & Shai Secunda Footnote: the Movie! Ruth Gavison The Nation of Israel? Philip Getz Birthright & Diaspora PLUS Did Billie Holiday Sing Yo's Blues? Sermons & Anti-Sermons & MORE Editor Abraham Socher Publisher Eric Cohen The history of America — Senior Contributing Editor one fear, one monster, Allan Arkush Editorial Board at a time Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri “An unexpected guilty pleasure! Poole invites us Leora Batnitzky into an important and enlightening, if disturbing, Ruth Gavison conversation about the very real monsters that Moshe Halbertal inhabit the dark spaces of America’s past.” Hillel Halkin – J. Gordon Melton, Institute for the Study of American Religion Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira “A well informed, thoughtful, and indeed frightening Michael Walzer angle of vision to a compelling American desire to J. H.H. Weiler be entertained by the grotesque and the horrific.” Leon Wieseltier – Gary Laderman, Emory University Ruth R. Wisse Available in October at fine booksellers everywhere. Steven J. Zipperstein Assistant Editor Philip Getz Art Director Betsy Klarfeld Business Manager baylor university press Lori Dorr baylorpress.com Interns Kif Leswing Arielle Orenstein The Jewish Review of Books (Print ISSN 2153-1978, An eloquent intellectual Online ISSN 2153-1994) is a quarterly publication of ideas and criticism published in Spring, history of the human Summer, Fall, and Winter, by Bee.Ideas, LLC., 745 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1400, New York, NY 10151. -

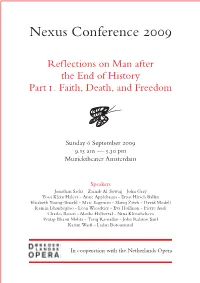

Nexus Conference 2009

Nexus Conference 2009 Reflections on Man after the End of History Part i . Faith, Death, and Freedom Sunday 6 September 2009 9.15 am — 5.30 pm Muziektheater Amsterdam Speakers Jonathan Sacks - Zainab Al-Suwaij - John Gray Yossi Klein Halevi - Anne Applebaum - Ernst Hirsch Ballin Elisabeth Young-Bruehl - Marc Sageman - Slavoj Žižek - David Modell Ramin Jahanbegloo - Leon Wieseltier - Eva Hoffman - Pierre Audi Charles Rosen - Moshe Halbertal - Nina Khrushcheva Pratap Bhanu Mehta - Tariq Ramadan - John Ralston Saul Karim Wasfi - Ladan Boroumand In cooperation with the Netherlands Opera Attendance at Nexus Conference 2009 We would be happy to welcome you as a member of the audience, but advance reservation of an admission ticket is compulsory. Please register online at our website, www.nexus-instituut.nl, or contact Ms. Ilja Hijink at [email protected]. The conference admission fee is € 75. A reduced rate of € 50 is available for subscribers to the periodical Nexus, who may bring up to three guests for the same reduced rate of € 50. A special youth rate of € 25 will be charged to those under the age of 26, provided they enclose a copy of their identity document with their registration form. The conference fee includes lunch and refreshments during the reception and breaks. Only written cancellations will be accepted. Cancellations received before 21 August 2009 will be free of charge; after that date the full fee will be charged. If you decide to register after 1 September, we would advise you to contact us by telephone to check for availability. The Nexus Conference will be held at the Muziektheater Amsterdam, Amstel 3, Amsterdam (parking and subway station Waterlooplein; please check details on www.muziektheater.nl). -

1 Beginning the Conversation

NOTES 1 Beginning the Conversation 1. Jacob Katz, Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times (New York: Schocken, 1969). 2. John Micklethwait, “In God’s Name: A Special Report on Religion and Public Life,” The Economist, London November 3–9, 2007. 3. Mark Lila, “Earthly Powers,” NYT, April 2, 2006. 4. When we mention the clash of civilizations, we think of either the Spengler battle, or a more benign interplay between cultures in individual lives. For the Spengler battle, see Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). For a more benign interplay in individual lives, see Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999). 5. Micklethwait, “In God’s Name.” 6. Robert Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). “Interview with Robert Wuthnow” Religion and Ethics Newsweekly April 26, 2002. Episode no. 534 http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week534/ rwuthnow.html 7. Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity, 291. 8. Eric Sharpe, “Dialogue,” in Mircea Eliade and Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of Religion, first edition, volume 4 (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 345–8. 9. Archbishop Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (London: SPCK, 2006). 10. Lily Edelman, Face to Face: A Primer in Dialogue (Washington, DC: B’nai B’rith, Adult Jewish Education, 1967). 11. Ben Zion Bokser, Judaism and the Christian Predicament (New York: Knopf, 1967), 5, 11. 12. Ibid., 375. -

A Tribute to Amos Oz Z”L Parashat Va'era January 5, 2019; 28 Tevet

A Tribute to Amos Oz z”l Parashat Va’era January 5, 2019; 28 Tevet 5779 Rabbi Adam J. Raskin, Congregation Har Shalom I am completely intimidated by the thought of sitting down to a cup of Turkish coffee and conversation with Amos Oz. While I have such profound respect and admiration for Israel’s towering author-laureate who died just this past Friday, there is something about him that sort-of terrifies me. First of all, Amos Oz was a Hebrew language elitist…He once announced in a public discussion with British Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks that “there is no difference between the castration of the Hebrew language by the Orthodox, the Reform, or the Conservative movement. They represent a unified front.” Oz felt that Hebrew was the one and only common denominator among Jews from all over the world, and all different religious and cultural pursuasions. And he was deeply dismayed by the relatively poor quality of the Hebrew language, even as spoken today in the modern State of Israel. I am sure that he would not approve of my conversational but less than fluent Hebrew. Oz was also an ardent secular Jew. He rejected ideas of promised land, or messianism, or destiny, or mission, or miracle. He once said about his fellow Israelis: “We are six and a half million citizens, six and a half million prime ministers, six and a half million prophets, six and a half million Messiahs, and everyone shouts at the same time and no one listens. Only I sometimes listen, [and] that is how I make a living.” So why am I mourning for a high-brow Hebraist who rejected the fundamental tenets of my faith, who once declared “I cannot use such words as ‘the promised land’ or the ‘promised borders’ because I do not believe in the one who made the promise?” Why do I feel that the State of Israel and the Jewish people have suffered a profound loss with the death of Amos Oz? Well, let me tell you… Amos Klausner was born in Jerusalem, 9 years before David Ben Gurion declared the establishment of the State of Israel. -

Dossier De Prensa Internacional Nº1. Especial Elcano Crisis En El Mundo

DOSSIER PRENSA INTERNACIONAL Nº 16 Del 1 al 8 de junio de 2011 • “Printemps arabe : une soif de dignité globalisée”. Alexandre Melnik. Le Monde. 30/06/2011 • “How to depose Kadafi”. Editorial. Los Angeles Times. 30/06/2011 • “In Tunisia and Egypt, still waiting on real change”. By Anne Applebaum. The Washington Post. 30/06/2011 • “Yet Again in Sudan”. By Nicholas D. Kristof. The New York Times. 30/06/2011 • “Iran's war games go underground”, Robert Fisk. The Independent. 29/06/2011 • “Assad deserves a swift trip to The Hague”. By Madeleine Albright and Marwan Muasher. Financial Times. 29/06/2011 • “All in for freedom in Syria”. By Nazir al-Abdo. Los Angeles Times. 29/06/2011 • “La guerre en Libye protège Bachar Al-Assad”. Pascal Boniface. Le Monde. 28/10/2011 • “We in Burma envy Egypt’s quick and easy revolution”. Aung San Suu Kyi. The Times. 28/06/2011 • “Lacking aim, support and cash, Nato still bombs Libya”. Andrew Murrray. The Guardian. 28/06/2011 • “Indicting Gadhafi”. Editorial. The Wall Street Journal. 28/06/2011 • "Le Hezbollah rapatrie son arsenal de Syrie". Par Georges Malbrunot. Le Figaro. 27/06/2011 • "Syrie : lettre au Conseil de sécurité de l’ONU". Par Woody Allen, Umberto Eco, David Grossman, Bernard-Henri Lévy, Amos Oz, Orhan Pamuk, Salman Rushdie, Wole Soyinka. Liberation. 27/06/2011 • “In Syria, an opening for the West to bring about Assad’s downfall”. By Ausama Monajed. The Washington Post. 27/06/2011 • “My Syria, Awake Again After 40 Years”. By MOHAMMAD ALI ATASSI. The New York Times. -

The New Middle East © Rabbi Richard A. Block the Temple

The New Middle East © Rabbi Richard A. Block The Temple – Tifereth Israel, Beachwood OH Rosh Hashanah 5775/2014 The story is told of a visitor to Jerusalem’s Biblical Zoo who saw that each enclosure bore a sign with a pertinent biblical quotation. One quoted Isaiah, “[T]he wolf and the lamb shall dwell together.” Across the moat separating the animals from visitors, he saw that a wolf and a lamb were, indeed, resting peaceably, side by side. Amazed, he sought out the zookeeper and asked how that was possible. “It’s simple,” the zookeeper replied. “Every day we put in a new lamb.” This tale captures the yawning chasm between the ideal world our tradition commands us to seek and the real world we inhabit. This summer, that chasm seemed wider than ever, as Israel found its cities and citizens under relentless, indiscriminate bombardment and terrorists swarmed through tunnels to kill and kidnap. Hamas’ instigation of hostilities and its refusal to accept or honor a series of ceasefires, compelled Israel to defend itself, with the awful consequences that war always brings. As the New Year begins, I want to state some fundamental facts about the conflict and discuss their implications. First, some fundamental facts about Israel: Israel is deeply invested in peace and wants a better life for all. Having known little but war since it was born in 1948, no country yearns for peace more passionately than Israel. That is why it gave up the entire Sinai for peace with Egypt, made peace with Jordan, left Lebanon, left all 1 of Gaza, and offered 97% of the West Bank for a Palestinian state. -

Rhetorics of Belonging

Rhetorics of Belonging Postcolonialism across the Disciplines 14 Bernard, Rhetorics of Belonging.indd 1 09/09/2013 11:17:03 Postcolonialism across the Disciplines Series Editors Graham Huggan, University of Leeds Andrew Thompson, University of Exeter Postcolonialism across the Disciplines showcases alternative directions for postcolonial studies. It is in part an attempt to counteract the dominance in colonial and postcolonial studies of one particular discipline – English literary/ cultural studies – and to make the case for a combination of disciplinary knowledges as the basis for contemporary postcolonial critique. Edited by leading scholars, the series aims to be a seminal contribution to the field, spanning the traditional range of disciplines represented in postcolonial studies but also those less acknowledged. It will also embrace new critical paradigms and examine the relationship between the transnational/cultural, the global and the postcolonial. Bernard, Rhetorics of Belonging.indd 2 09/09/2013 11:17:03 Rhetorics of Belonging Nation, Narration, and Israel/Palestine Anna Bernard Liverpool University Press Bernard, Rhetorics of Belonging.indd 3 09/09/2013 11:17:03 First published 2013 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2013 Anna Bernard The right of Anna Bernard to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or