Margalit Halbertal Liberalism and the Right to Culture.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M E O R O T a Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (Formerly Edah Journal)

M e o r o t A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly Edah Journal) Tishrei 5770 Special Edition on Modern Orthodox Education CONTENTS Editor’s Introduction to Special Tishrei 5770 Edition Nathaniel Helfgot SYMPOSIUM On Modern Orthodox Day School Education Scot A. Berman, Todd Berman, Shlomo (Myles) Brody, Yitzchak Etshalom,Yoel Finkelman, David Flatto Zvi Grumet, Naftali Harcsztark, Rivka Kahan, Miriam Reisler, Jeremy Savitsky ARTICLES What Should a Yeshiva High School Graduate Know, Value and Be Able to Do? Moshe Sokolow Responses by Jack Bieler, Yaakov Blau, Erica Brown, Aaron Frank, Mark Gottlieb The Economics of Jewish Education The Tuition Hole: How We Dug It and How to Begin Digging Out of It Allen Friedman The Economic Crisis and Jewish Education Saul Zucker Striving for Cognitive Excellence Jack Nahmod To Teach Tsni’ut with Tsni’ut Meorot 7:2 Tishrei 5770 Tamar Biala A Publication of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah REVIEW ESSAY Rabbinical School © 2009 Life Values and Intimacy Education: Health Education for the Jewish School, Yocheved Debow and Anna Woloski-Wruble, eds. Jeffrey Kobrin STATEMENT OF PURPOSE Meorot: A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly The Edah Journal) Statement of Purpose Meorot is a forum for discussion of Orthodox Judaism’s engagement with modernity, published by Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School. It is the conviction of Meorot that this discourse is vital to nurturing the spiritual and religious experiences of Modern Orthodox Jews. Committed to the norms of halakhah and Torah, Meorot is dedicated -

The Prevention of Unjust Wars

The Prevention of Unjust Wars 1 The Doctrine of the Permissibility of Participation War is a great moral evil. … The first great moral challenge of war, then, is: prevention. For most possible wars the best response is prevention. Occasionally, a war may be the least available evil among a bad lot of choices. Since war always involves the commission of so much wrongful killing and injuring, making war itself a supreme evil, a particular war can be the least available evil only if it prevents, or anyhow is likely to prevent, an alternative evil that is very great indeed.1 This passage from a recent paper by Henry Shue and Janina Dill articulates a view of war that is hard to challenge, even for those who are antipathetic to pacifism. It is echoed in the succinct claim of Michael Walzer and Avishai Margalit that “the point of just war theory is to regulate warfare, to limit its occasions.”2 These are, I take it, claims about war understood as a phenomenon comprising the belligerent acts of all the parties to a conflict. The Second World War was a war in this sense, one that was clearly a great evil, though if the only alternative to its occurrence was the unopposed conquest of Europe by the Nazis, it was an evil that Shue and Dill would presumably concede to have been the “least available evil” in the circumstances. Notice, however, that the Second World War was neither a just war nor an unjust war; rather, it comprised both just and unjust wars. -

The Rebbe and the Yak

Hillel Halkin on King James: The Harold Bloom Version JEWISH REVIEW Volume 2, Number 3 Fall 2011 $6.95 OF BOOKS Alan Mintz The Rebbe and the Yak Ruth R. Wisse Yehudah Mirsky Adam Kirsch Moshe Halbertal The Faith of Reds On Law & Forgiveness Yehuda Amital Elli Fischer & Shai Secunda Footnote: the Movie! Ruth Gavison The Nation of Israel? Philip Getz Birthright & Diaspora PLUS Did Billie Holiday Sing Yo's Blues? Sermons & Anti-Sermons & MORE Editor Abraham Socher Publisher Eric Cohen The history of America — Senior Contributing Editor one fear, one monster, Allan Arkush Editorial Board at a time Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri “An unexpected guilty pleasure! Poole invites us Leora Batnitzky into an important and enlightening, if disturbing, Ruth Gavison conversation about the very real monsters that Moshe Halbertal inhabit the dark spaces of America’s past.” Hillel Halkin – J. Gordon Melton, Institute for the Study of American Religion Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira “A well informed, thoughtful, and indeed frightening Michael Walzer angle of vision to a compelling American desire to J. H.H. Weiler be entertained by the grotesque and the horrific.” Leon Wieseltier – Gary Laderman, Emory University Ruth R. Wisse Available in October at fine booksellers everywhere. Steven J. Zipperstein Assistant Editor Philip Getz Art Director Betsy Klarfeld Business Manager baylor university press Lori Dorr baylorpress.com Interns Kif Leswing Arielle Orenstein The Jewish Review of Books (Print ISSN 2153-1978, An eloquent intellectual Online ISSN 2153-1994) is a quarterly publication of ideas and criticism published in Spring, history of the human Summer, Fall, and Winter, by Bee.Ideas, LLC., 745 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1400, New York, NY 10151. -

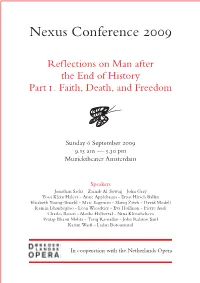

Nexus Conference 2009

Nexus Conference 2009 Reflections on Man after the End of History Part i . Faith, Death, and Freedom Sunday 6 September 2009 9.15 am — 5.30 pm Muziektheater Amsterdam Speakers Jonathan Sacks - Zainab Al-Suwaij - John Gray Yossi Klein Halevi - Anne Applebaum - Ernst Hirsch Ballin Elisabeth Young-Bruehl - Marc Sageman - Slavoj Žižek - David Modell Ramin Jahanbegloo - Leon Wieseltier - Eva Hoffman - Pierre Audi Charles Rosen - Moshe Halbertal - Nina Khrushcheva Pratap Bhanu Mehta - Tariq Ramadan - John Ralston Saul Karim Wasfi - Ladan Boroumand In cooperation with the Netherlands Opera Attendance at Nexus Conference 2009 We would be happy to welcome you as a member of the audience, but advance reservation of an admission ticket is compulsory. Please register online at our website, www.nexus-instituut.nl, or contact Ms. Ilja Hijink at [email protected]. The conference admission fee is € 75. A reduced rate of € 50 is available for subscribers to the periodical Nexus, who may bring up to three guests for the same reduced rate of € 50. A special youth rate of € 25 will be charged to those under the age of 26, provided they enclose a copy of their identity document with their registration form. The conference fee includes lunch and refreshments during the reception and breaks. Only written cancellations will be accepted. Cancellations received before 21 August 2009 will be free of charge; after that date the full fee will be charged. If you decide to register after 1 September, we would advise you to contact us by telephone to check for availability. The Nexus Conference will be held at the Muziektheater Amsterdam, Amstel 3, Amsterdam (parking and subway station Waterlooplein; please check details on www.muziektheater.nl). -

1 Beginning the Conversation

NOTES 1 Beginning the Conversation 1. Jacob Katz, Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times (New York: Schocken, 1969). 2. John Micklethwait, “In God’s Name: A Special Report on Religion and Public Life,” The Economist, London November 3–9, 2007. 3. Mark Lila, “Earthly Powers,” NYT, April 2, 2006. 4. When we mention the clash of civilizations, we think of either the Spengler battle, or a more benign interplay between cultures in individual lives. For the Spengler battle, see Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). For a more benign interplay in individual lives, see Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999). 5. Micklethwait, “In God’s Name.” 6. Robert Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). “Interview with Robert Wuthnow” Religion and Ethics Newsweekly April 26, 2002. Episode no. 534 http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week534/ rwuthnow.html 7. Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity, 291. 8. Eric Sharpe, “Dialogue,” in Mircea Eliade and Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of Religion, first edition, volume 4 (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 345–8. 9. Archbishop Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (London: SPCK, 2006). 10. Lily Edelman, Face to Face: A Primer in Dialogue (Washington, DC: B’nai B’rith, Adult Jewish Education, 1967). 11. Ben Zion Bokser, Judaism and the Christian Predicament (New York: Knopf, 1967), 5, 11. 12. Ibid., 375. -

A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Map .................................................................................................................................. i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions of Apartheid and Persecution ................................................................................. -

B'tselem Report: Dispossession & Exploitation: Israel's Policy in the Jordan Valley & Northern Dead Sea, May

Dispossession & Exploitation Israel's policy in the Jordan Valley & northern Dead Sea May 2011 Researched and written by Eyal Hareuveni Edited by Yael Stein Data coordination by Atef Abu a-Rub, Wassim Ghantous, Tamar Gonen, Iyad Hadad, Kareem Jubran, Noam Raz Geographic data processing by Shai Efrati B'Tselem thanks Salwa Alinat, Kav LaOved’s former coordinator of Palestinian fieldworkers in the settlements, Daphna Banai, of Machsom Watch, Hagit Ofran, Peace Now’s Settlements Watch coordinator, Dror Etkes, and Alon Cohen-Lifshitz and Nir Shalev, of Bimkom. 2 Table of contents Introduction......................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter One: Statistics........................................................................................................ 8 Land area and borders of the Jordan Valley and northern Dead Sea area....................... 8 Palestinian population in the Jordan Valley .................................................................... 9 Settlements and the settler population........................................................................... 10 Land area of the settlements .......................................................................................... 13 Chapter Two: Taking control of land................................................................................ 15 Theft of private Palestinian land and transfer to settlements......................................... 15 Seizure of land for “military needs”............................................................................. -

Editors' Interview with Michael Walzer

[50] JOURNAL OF POLITICAL THOUGHT INTERVIEW [with Michael Walzer] Michael Walzer is a prominent American political theorist and public intel- lectual. A professor emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princ- eton, New Jersey, he is co-editor of Dissent, an intellectual magazine that he has been affiliated with since his years as an undergraduate at Brandeis University. He has written about a wide variety of topics in political theory and moral philosophy, including political obligation, just and unjust war, nationalism and ethnicity, economic justice, and the welfare state. He has played a critical role in the revival of a practical, issue-focused ethics and in the development of a pluralist approach to political and moral life. Wal- zer’s books include Just and Unjust Wars (1977), On Toleration (1997), and Spheres of Justice (1983). We sat down with him in May for a wide- ranging conversation on the interplay between personal identity and po- litical thought, the state of political theory today, and the overlapping chal- lenges posed by religion and ethnicity for the contemporary nation-state. I. Identity and the Political interested in left-issue politics. Theory License My teachers at Brandeis told me I should apply to graduate school JPT: What first drew you to the in political science, because it field of political theory? wasn’t really a field and you could do whatever you wanted. Whereas MW: When I was a history major in history you would be commit- at Brandeis, I was first interested ted to archival research, in politi- in studying the history of ideas. -

The National Left (First Draft) by Shmuel Hasfari and Eldad Yaniv

The National Left (First Draft) by Shmu'el Hasfari and Eldad Yaniv Open Source Center OSC Summary: A self-published book by Israeli playwright Shmu'el Hasfari and political activist Eldad Yaniv entitled "The National Left (First Draft)" bemoans the death of Israel's political left. http://www.fas.org/irp/dni/osc/israel-left.pdf Statement by the Authors The contents of this publication are the responsibility of the authors, who also personally bore the modest printing costs. Any part of the material in this book may be photocopied and recorded. It is recommended that it should be kept in a data-storage system, transmitted, or recorded in any form or by any electronic, optical, mechanical means, or otherwise. Any form of commercial use of the material in this book is permitted without the explicit written permission of the authors. 1. The Left The Left died the day the Six-Day War ended. With the dawn of the Israeli empire, the Left's sun sank and the Small [pun on Smol, the Hebrew word for Left] was born. The Small is a mark of Cain, a disparaging term for a collaborator, a lover of Arabs, a hater of Israel, a Jew who turns against his own people, not a patriot. The Small-ists eat pork on Yom Kippur, gobble shrimps during the week, drink espresso whenever possible, and are homos, kapos, artsy-fartsy snobs, and what not. Until 1967, the Left actually managed some impressive deeds -- it took control of the land, ploughed, sowed, harvested, founded the state, built the army, built its industry from scratch, fought Arabs, settled the land, built the nuclear reactor, brought millions of Jews here and absorbed them, and set up kibbutzim, moshavim, and agriculture. -

Reading Oz with Kashua

MINORIT ARIAN INTERVENTIONS AND NATIONAL IDENTITY: READING OZ WITH KASHUA Ari Ofengenden Brandeis University The "other" is never outside or beyond us; it emerges forcefully, within cultural discourse, when we think we speak most intimately and indigenously "between ourselves" (Homi Bhabha) This article attempts to read Amos Oz's celebrated autobiography, A Tale of Love and Darkness , with Sayed Kashua's autobiographical texts Dancing Arabs and Let it be Morning , as well as his television sitcom Arab Labor. Dif- ferences between the two authors are immediately apparent. More than perhaps any other writer, Oz represents the Zionist core of the political and literary establishment in Israel, as his autobiographical novel depicts one of the most important families in the early Israeli intelligentsia. Conversely, Kashua is a Palestinian Israeli and thus part of the most marginalized minority in Israeli society.1 I would like to complicate this picture of center and periphery by bringing out the major writer in Kashua and the minor writer in Oz. It is also my intention to expose the complimentary and reciprocal relations between the positions that they occupy. Thus, the article attempts to argue against a simple one-to-one correspondence between the centrality or marginal ity of an author's political position and the centrality or marginality of his or her literary en- deavors. In addition, both writers mobilize their own minority narrative and ap- peal to the traditional minority position of Judaism to bring about positive trans- formation. Amos Oz inhabits a special place in Hebrew literature. The most influential Hebrew writer in contemporary Israel and the best-selling Israeli author abroad, he is also a very influential political essayist and commentator. -

Global Expert Mission Israel Precision Medicine 2020

Connecting for Positive Change _ ktn-uk.org/Global Global Expert Mission Israel Precision Medicine 2020 Contact Dr Sandeep Sandhu Knowledge Transfer Manager – International & Development [email protected] ISRAEL PRECISION MEDICINE 2020 Contents Welcome 5 1 Introduction 6 1.1 Start-Up Nation and Current Support of Innovation in Israel 6 1.1.1 Who Funds Innovation in Israel? 6 1.1.2 Who Approves New Medicines and Technologies in Israel? 7 1.1.3 Who Provides Healthcare and Health Insurance in Israel? 7 1.2 A Culture of Entrepreneurship 8 1.3 A Network of Support 8 1.4 Academic Foundations 8 1.5 The Geography of Innovation 9 1.6 The Challenge of Translation 9 1.7 Precision Medicine in Israel 9 1.7.1 Drug Discovery and Precision Medicine 10 1.7.2 Clinical Trials and Precision Medicine 10 1.7.3 Key Policies and Mechanisms Supporting Precision Medicine 11 2 Current Collaborations and Synergies 12 2.1 Existing Mechanisms for Collaboration Between the UK and Israel 12 2.1.1 UK Science and Innovation Network in Israel 12 2.1.2 UK-Israel Tech Hub 12 2.1.3 UK-Israel Science Council 12 2.1.4 Britain Israel Research and Academic Exchange Partnership (BIRAX) 12 2.1.5 UK-Israel Memorandum of Understanding in Innovation 13 2.1.6 UK-Israel Memorandum of Understanding in Bilateral Science and Technology 13 2.2 Synergistic Themes 13 2.2.1 Data - UK Biobank, NHS and Israeli Medical Records 13 2.2.2 The Concept of Bio-Convergence 14 3 Fertile Areas for Inspiration and Collaboration 16 3.1 Working with our Similarities 16 3.1.1 The UK-Israel Academic -

Proportionality in Warfare Keith Pavlischek

Proportionality in Warfare Keith Pavlischek The last two times Israel went to war, international commentators crit- icized the country’s use of force as “disproportionate.” During the Israel- Hezbollah war in 2006, officials from the United Nations, the European Union, and several countries used that word to describe Israel’s mili- tary actions in Lebanon. Coverage in the press was similar—one news- paper columnist, for example, criticized the “utterly disproportionate... carnage.” Two and a half years later, during the Gaza War of 2008-09, the same charge was leveled against Israel by some of the same institu- tions and individuals; it also appeared throughout the controversial U.N. report about the conflict (the “Goldstone Report”). This criticism reveals an important moral misunderstanding. In everyday usage, the word “proportional” implies numerical comparability, and that seems to be what most of Israel’s critics have in mind: the ethics of war, they suggest, requires something like a tit-for-tat response. So if the number of losses suffered by Hezbollah or Hamas greatly exceeds the number of casualties among the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), then Israel is morally and perhaps legally culpable for the “disproportionate” casualties. But these critics seem largely unaware that “proportionality” has a technical meaning connected to the ethics of war. The long tradition of just war theory distinguishes between the principles governing the justice of going to war (jus ad bellum) and those governing just con- duct in warfare (jus in bello). There are two main jus in bello criteria. The criterion of discrimination prohibits direct and intentional attacks on noncombatants, although neither international law nor the just war tradition that has morally informed it requires that a legitimate military target must be spared from attack simply because its destruction may unintentionally injure or kill noncombatants or damage civilian property and infrastructure.