I-Xiv Front Matter.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tomorrow's Schools 20 Years On

Thinking research Tomorrow’s Schools 20 years on... Edited by John Langley Tomorrow’s Schools 20 years on... Edited by John Langley Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 CHAPTER 1 Dr. John Langley 5 Introduction CHAPTER 2 Harvey McQueen 19 Towards a covenant CHAPTER 3 Wyatt Creech 29 Twenty years on CHAPTER 4 Howard Fancy 39 Re-engineering the shifts in the system CHAPTER 5 Elizabeth Eppel 51 Curriculum, teaching and learning: A celebratory review of a very complex and evolving landscape CHAPTER 6 Barbara Disley 63 Can we dare to think of a world without special education? CHAPTER 7 Terry Bates 79 National mission or mission improbable? CHAPTER 8 Brian Annan 91 Schooling improvement since Tomorrow’s Schools CHAPTER 9 Margaret Bendall 105 A leadership perspective Published by Cognition Institute, 2009. ISBN: 978-0-473-15955-9 CHAPTER 10 John Hattie 121 ©Cognition Institute, 2009. Tomorrow’s Schools - yesterday’s news: The quest for a new metaphor All rights reserved. No portion of this publication, printed or CHAPTER 11 Cathy Wylie 135 electronic, may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without Getting more from school self-management the express written consent of the publisher. For more information, email [email protected] CHAPTER 12 Phil Coogan and Derek Wenmoth 149 www.cognitioninstitute.org Tomorrow’s Web for our future learning 1 Acknowledgements The Cognition Education Research Trust (CERT) has a growing network of people and organisations participating in and contributing to the achievement of our philanthropic purposes. There are many who have enabled and contributed to this first thought leader publication on ‘Tomorrow’s Schools Twenty Years On’. -

Is There a Civil Religious Tradition in New Zealand

The Insubstantial Pageant: is there a civil religious tradition in New Zealand? A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies in the University of Canterbury by Mark Pickering ~ University of Canterbury 1985 CONTENTS b Chapter Page I (~, Abstract Preface I. Introduction l Plato p.2 Rousseau p.3 Bellah pp.3-5 American discussion on civil religion pp.S-8 New Zealand discussion on civil religion pp.S-12 Terms and scope of study pp.l2-14 II. Evidence 14 Speeches pp.lS-25 The Political Arena pp.25-32 Norman Kirk pp.32-40 Waitangi or New Zealand Day pp.40-46 Anzac Day pp.46-56 Other New Zealand State Rituals pp.56-61 Summary of Chapter II pp.6l-62 III. Discussion 63 Is there a civil religion in New Zealand? pp.64-71 Why has civil religion emerged as a concept? pp.71-73 What might be the effects of adopting the concept of civil religion? pp.73-8l Summary to Chapter III pp.82-83 IV. Conclusion 84 Acknowledgements 88 References 89 Appendix I 94 Appendix II 95 2 3 FEB 2000 ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with the concept of 'civil religion' and whether it is applicable to some aspects of New zealand society. The origin, development and criticism of the concept is discussed, drawing on such scholars as Robert Bellah and John F. Wilson in the United States, and on recent New Zealand commentators. Using material such as Anzac Day and Waitangi Day commemorations, Governor-Generals' speeches, observance of Dominion Day and Empire Day, prayers in Parliament, the role of Norman Kirk, and other related phenomena, the thesis considers whether this 'evidence' substantiates the existence of a civil religion. -

MAYORS, MAORI and EMPLOYMENT

The Jobs Letter No. 130 8 September 2000 Essential Information on an Essential Issue • More than fifty beneficiary advocates from Northland to Invercargill KEY met last week with Government Ministers, the Department of Work and Income (Winz) and Ministry of Social Policy (MSP). They discussed MAYORS MEET MAORI progress on a list of 123 recommendations of immediate changes that the advocates want to see Winz and other departments implement in AN EMPLOYMENT STRATEGY order to assist those living on a benefit. ADVOCATES MEET GOVERNMENT The Conference took place at Tatum Park near Levin, and was addressed by Ruth Dyson, Associate Minister of Social Services and Employment and CEG APPOINTMENT Parekura Horomia, Minister of Maori Affairs. The ministers later said that the INCOME AND JOB INSECURITY government “valued its ongoing relationship with the advocates...” CEOs Robert Reid, President of Unite! and spokesperson for the advocate groups says that the conference enabled a wide group to consider the recommendations from the advocates and to discuss what progress had been made on them by the departments. The meeting also included DIARY workshops with representatives from Winz, MSP, Department of La- 16 August 2000 bour, Ministry of Economic Development and Housing New Zealand. Representatives from the Labour, Alliance and Green Parties were Parliament’s finance committee endorses a policy that govern- invited to the final session of the conference. ment departments buy NZ-made goods and services “where cost There will now be regional meetings held between beneficiary advocate groups effective”. The Industrial Supplies and the Winz Regional Commissioners. Maori beneficiary advocates have Office, which filters government formed their own network and have been invited to be involved in the Winz purchasing, says that every $1m of import substitution saves 16 Maori structures. -

Friend Or Ally? a Question for New Zealand

.......... , ---~ MeN AIR PAPERS NUMBER T\\ ELVE FRIEND OR ALLY? A QUESTION FOR NEW ZEALAND By EWAN JAMIESON THE INSTI FUTE FOR NATIONAL SI'R-~TEGIC STUDIES ! I :. ' 71. " " :~..? ~i ~ '" ,.Y:: ;,i:,.i:".. :..,-~.~......... ,,i-:i:~: .~,.:iI- " yT.. -.~ .. ' , " : , , ~'~." ~ ,?/ .... ',~.'.'.~ ..~'. ~. ~ ,. " ~:S~(::!?- ~,i~ '. ? ~ .5" .~.: -~:!~ ~:,:i.. :.~ ".: :~" ;: ~:~"~',~ ~" '" i .'.i::.. , i ::: .',~ :: .... ,- " . ".:' i:!i"~;~ :~;:'! .,"L': ;..~'~ ',.,~'i:..~,~'"~,~: ;":,:.;;, ','" ;.: i',: ''~ .~,,- ~.:.~i ~ . '~'">.'.. :: "" ,-'. ~:.." ;';, :.~';';-;~.,.";'."" .7 ,'~'!~':"~ '?'""" "~ ': " '.-."i.:2: i!;,'i ,~.~,~I~out ;popular: ~fo.rmatwn~ .o~~'t,he~,,:. "~.. " ,m/e..a~ tg:,the~6w.erw!~chi~no.wtetl~e.~gi..~e~ ;~i:~.::! ~ :: :~...i.. 5~', '+~ :: ..., .,. "'" .... " ",'.. : ~'. ,;. ". ~.~.~'.:~.'-? "-'< :! :.'~ : :,. '~ ', ;'~ : :~;.':':/.:- "i ; - :~:~!II::::,:IL:.~JmaiegMad}~)~:ib;:, ,?T,-. B~;'...-::', .:., ,.:~ .~ 'z • ,. :~.'..." , ,~,:, "~, v : ", :, -:.-'": ., ,5 ~..:. :~i,~' ',: ""... - )" . ,;'~'.i "/:~'-!"'-.i' z ~ ".. "', " 51"c, ' ~. ;'~.'.i:.-. ::,,;~:',... ~. " • " ' '. ' ".' ,This :iis .aipul~ ~'i~gtin~e ..fdi;:Na~i~real..Sfi'~te~ie.'Studi'~ ~It ;is, :not.i! -, - .... +~l~ase,~ad.~ p,g, ,,.- .~, . • ,,. .... .;. ...~,. ...... ,._ ,,. .~ .... ~;-, :'-. ,,~7 ~ ' .~.: .... .,~,~.:U7 ,L,: :.~: .! ~ :..!:.i.i.:~i :. : ':'::: : ',,-..-'i? -~ .i~ .;,.~.,;: ~v~i- ;. ~, ~;. ' ~ ,::~%~.:~.. : ..., .... .... -, ........ ....... 1'-.~ ~:-~...%, ;, .i-,i; .:.~,:- . eommenaati6'r~:~xpregseff:or ;ii~iplie'd.:;~ifl~in.:iat~ -:: -

Spring Fling

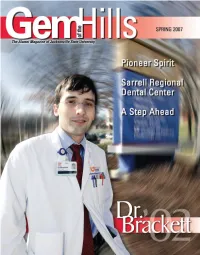

insurance administrator to human resources of the manager, all providing free services to GemThe Alumni Magazine of JacksonvilleHills State University deserving children with Medicaid or ALL- Vol. XIII, No. 2 KIDS insurance. Additional details about the JSU President dreams the center has and the ones they fulfill William A. Meehan, Ed.D., ’72/’76 are located on page 12. Vice President for Institutional Many patients at Erlanger Hospital in Advancement Chattanooga, Tenn. are also benefiting from Joseph A. Serviss, ’69/’75 a JSU alumnus thanks to the skills of Dr. Alumni Association President Stephen Brackett. The feature story on page Sarah Ballard,’69/’75/’82 15 tracks Brackett’s life from his decision to Director of Alumni Affairs and Editor attend JSU to his current life as a hospital Kaci Ogle, ’95/’04 resident. Art Director With a “STEP” in the right direction, Mary Smith, ’93 JSU’s College of Nursing and Health Sciences Staff Artists Dr. William A. Meehan, President Strategic Teaching for Enhanced Professional Erin Hill, ’01/’05 Preparation Program (page 18) is succeeding Rusty Hill in helping licensed RNs obtain higher Graham Lewis Dear Alumni, education goals while still fulfilling personal Copyeditor/Proofreader and occupational duties. Sybil Roark tells Gem Erin Chupp, ’05 In this issue, JSU alumni in healthcare how she returned to JSU for her master’s in Gloria Horton professions and the College of Nursing and nursing while working and raising children. In Staff Writers Health Sciences are highlighted as one of this article she explains how she searched for “a Al Harris, ’81/’91 the outstanding sectors of Jacksonville State quality education” and why JSU had “the best Anne Muriithi University. -

RTI Study by Steven Price

1 I INTRODUCTION Introducing the Official Information Bill to Parliament in 1981, the Minister of Justice called it "one of the most significant constitutional innovations to be made since the establishment of the office of the Ombudsmen in the early 1960s."1 Its goals were lofty: to "increase progressively the availability of official information" in order to promote democratic participation, political accountability and good government.2 Yet to hear some of the criticisms of the Official Information Act 1982 (OIA) now, one could be forgiven for wondering whether it has been much of an improvement over the Official Secrets Act 1951, which made releasing official information an offence.3 "Ministers and officials developed ways of routinely subverting the provisions of the Official Information Act", researcher Nicky Hager has written.4 "Journalists complain processing of requests takes too long, and accuse bureaucrats of abusing the system, especially if the material sought is remotely embarrassing or controversial", wrote investigative journalist Amanda Cropp.5 "It is ridiculously easy to circumvent the act and to hide information from requesters and Ombudsmen alike", wrote former MP Michael Laws recently: "Of course, all potentially embarrassing information is routinely refused and time delays are simply de rigueur."6 1 Hon J K McLay (23 July 1981) 439 NZPD 1908. 2 Official Information Act 1982, s 4 and long title. Note that the Act also aims "to protect official information to the extent consistent with the public interest and the preservation of personal privacy": Official Information Act 1982, s 4(c) and long title. 3 Official Secrets Act 1951, s 6. -

The New Zealand Connection

Chapter Eleven: The New Zealand Connection Professor Bob Catley A few weeks ago I sat ruminating with a very influential New Zealander. He mused that the Romans had controlled Britain for 400 years but that, when they left, within a short time little was left of them, other than ruins. This may be a parable applicable to New Zealand.1 The British abandoned New Zealand to its fate and joined the European Union in 1973. It is now rapidly becoming a Pacific country. In itself, this may be no bad thing. But the accompanying characteristics include: 〈 Its per capita income is now slipping quickly out of the high income or First World category, and stood in May, 2001 at $US11,200, when the World Bank cut-off point is around $US10,000. It has dropped from $US13,700 in 1999; 〈 Its demographic structure is increasingly non-European and Third World in origin and, despite having recently been the most British of Her Majesty’s Dominions, it may have a bare European majority within a generation; New Zealanders – mostly European – left at the rate of over two per cent a year (79,000) in May, 2000-01 and will not now naturally replace themselves; 〈 It has little control over its major institutions: its banking, other finance, media, energy and transportation systems are almost entirely run, and often are run badly, by foreigners; its universities, health system and housing stock decline to Second or Third World standards; and its crime, youth suicide and social dissonance rates rise to developed world record levels; 〈 Its remaining private corporations -

Methodist Conference 2016 Te Háhi Weteriana O Aotearoa

Methodist Conference 2016 Te Háhi Weteriana O Aotearoa CONFERENCE SUMMARY ̴ Moored to Christ, Moving into Mission ̴ The Annual Conference of the Methodist Church of New Zealand met at Wesley College in Paerata, Auckland from Saturday 1 October until Wednesday 5 October 2016 The intention of this record is to provide Conference delegates with summary material to report back to their congregations. This needs to be read in conjunction with the Conference sheets, where full lists of people involved, roles, and appointments will be found. That material and the formal record of decisions and minutes taken by Conference secretaries takes precedence over these more informal notes, for historical and legal purposes! Full proceedings and formal records of conference are available on the Methodist website, http://www.methodist.org.nz/conference/2016 Overseas Guests of Conference included: Rev Tevita Banivanua, President, Methodist Church in Fiji Rev Colleen Geyer, General Secretary, Uniting Church in Australia Rev Prof. Robert Gribbon, Official Representative, Uniting Church in Australia Rev Sandy Boyce (Deacon), Presidnet DIAKONIA World Federation, Uniting Church in Australia Rev Wilfred Kurepitu, Moderator, Uniting Church in Solomon Islands Rev Dr Finau ‘Ahio, President, Free Wesleyan Church of Tonga Rev Bill Mullally, President, Methodist Church of Ireland Rev Masunu Utumapu, Superintendent Auckland South Synod for Methodist Church in Samoa Page 1 Observers from Other New Zealand Churches: Sr. Sian Owen, Pompallier Diocesan Centre, Roman Catholic -

Investigating Commentary on the Fifth Labour-Led Government's Third Way Approach

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Research Commons@Waikato New Zealand Sociology 32(1) 2017 Page | 51 Investigating commentary on the fifth Labour-led government’s Third Way approach Gemma Piercy, Kate Mackness, Moana Rarere and Brendan Madley Abstract After the 1999 election of a Labour-led coalition government in Aotearoa New Zealand, a raft of policy reforms adopted characteristics of the ‘Third Way’ ideology promoted by Anthony Giddens. We argue, however, that Third Way characteristics were not implemented in Aotearoa New Zealand without attracting criticism. This article reviews academic analysis and wider commentary on the Third Way in Aotearoa New Zealand, much of which particularly focused on social policy reforms made by the Labour-led coalition government (1999-2008). We have used this literature to identify the varied ways in which the Third Way was defined and the extent to which Third Way ideology was considered to have influenced policy and practice the Aotearoa New Zealand context. Our semi-systematic literature review shows that many commentators argued that New Zealand did indeed implement a policy platform consistent with Third Way ideological characteristics but these were also adapted to the unique context of Aotearoa New Zealand. We explore in detail two key examples of adaptation discussed in the literature: the Labour-led government’s early focus on reducing inequalities between Māori and non-Māori and on renewing civil society through subsidiarity and a partnership approach. Keywords Third Way; Civil society; Partnership; Giddens; Fifth Labour-led government Introduction The fifth Labour-led coalition government (1999-2008) of Aotearoa New Zealand initiated a wide range of policy reforms which reflected values consistent with ‘Third Way’ ideology. -

Advertising and the Market Orientation of Political Parties Contesting the 1999 and 2002 New Zealand General Election Campaigns

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. ADVERTISING AND THE MARKET ORIENTATION OF POLITICAL PARTIES CONTESTING THE 1999 AND 2002 NEW ZEALAND GENERAL ELECTION CAMPAIGNS A THESIS PRESENTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICS AT MASSEY UNIVERSITY, PALMERSTON NORTH, NEW ZEALAND. CLAIRE ELIZABETH ROBINSON 2006 i ABSTRACT This thesis proposes an alternative way of establishing a link between market orientation and electoral success, by focusing on market orientation as a message instead of as a management function. Using interpretive textual analysis the thesis examines the advertising messages of the highest polling political parties for evidence of voter orientation and competitor orientation in the 1999 and 2002 New Zealand general election campaigns. Relating manifest market orientation to a number of statistical indicators of electoral success the thesis looks for plausible associations between the visual manifestation of market orientation in political advertisements and parties’ achievement of their party vote goals in the 1999 and 2002 elections. It offers party-focused explanations for electoral outcomes to complement existing voter-centric explanations, and adds another level of scholarly understanding of recent electoral outcomes in New Zealand. While the thesis finds little association between demonstration ofcompetitor orientation in political advertisements and electoral success, it finds a plausible relationship between parties that demonstrated a voter orientation in their political advertisements and goal achievement. -

Timing Is Everything

Chapter 2 The ANZACS, Part 1—The Frigate that wasn’t a Frigate As long ago as 1954 the cost of replacement frigates had been an issue. Almost a quarter of a century later, the 1978 Defence Review made the observation that `the high costs of acquiring and maintaining modern naval ships and systems compounds the difficulty of reaching decisions which will adequately provide for New Zealand's future needs at sea'.1 Indeed `extensive enquiries to find a replacement for HMNZS Otago made it clear that the cost of a new frigate had gone beyond what New Zealand could afford'.2 This observation led to the serious consideration of converting the Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN) to a coast guard service, but the Government rejected the notion on the basis that, although a coast guard could carry out resource protection tasks, it would mean the end of any strategic relationship with our ANZUS Treaty partners, and the RNZN would no longer be able to operate as a military force. The Chief of Naval Staff, Rear Admiral Neil D. Anderson, said that the New Zealand Government's commitment to maintaining a professional fighting navy was `a magnificent shot in the arm for everyone in the Navy'.3 The Government remained committed to a compact multi-purpose navy, and calculated that a core operational force of three ships would be the minimum necessary force. These ships were to be the Leander-class frigates HMNZS Waikato and HMNZS Canterbury (commissioned in 1966 and 1971 respectively), and the older Type 12 frigate HMNZS Otago. -

(No. 16)Craccum-1987-061-016.Pdf

T WANTED ST RECOVERY OR ALIVE Sts tl heir res V * , ALSO INSIDE:- ' | # i — Greenpeace on Ice — Crowded House — A World Without Balance — Referendum t. ) : Results J Volume 61 Issue 16 With the release of the Labour Government's policy on education, we see a well executed side-step F e a tu re s away from the issue of user pays in education. Their education policy Trapped in a World itself could be considered as a 'neither confirm nor deny' policy on cost recovery. Though Lange and Without Balance 3 Russell Marshall recently said that Labour has no intention of im l do Einstein, plementing cost recovery in educa S to p Press tion in the near future can we Monet, and Referendum Results believe them, and what exactly is It seems that AUSA Exec has voted (tehurch have in < the near future? Remember the last against the march by a vote of four surface one \ 4 to three. The fourth vote being iculty express election when Labour PROMISED US els... eccentric a living bursary and a fully subsidis Chair's casting vote. What does that, and for Day of Action ed job scheme. They abolished the mean? ter, they are all subsidised job scheme altogether Stop Press le with right bi 7 and have you had a look at your examine the bank balance lately? It seems that some individuals is clear that i Greenpeace on Ice It seems National are just as bad. have decided that the isue is too other feature: Their policy though pledging ac important and have decided to These ar 11 cess to education for all, introduces organise the march with their own the possibility of loans if you study funds.