Genetic Contributions to Behavioural Diversity at the Gene–Environment Interface

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lineage-Specific Mapping of Quantitative Trait Loci

Heredity (2013) 111, 106–113 & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0018-067X/13 www.nature.com/hdy ORIGINAL ARTICLE Lineage-specific mapping of quantitative trait loci C Chen1 and K Ritland We present an approach for quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping, termed as ‘lineage-specific QTL mapping’, for inferring allelic changes of QTL evolution along with branches in a phylogeny. We describe and analyze the simplest case: by adding a third taxon into the normal procedure of QTL mapping between pairs of taxa, such inferences can be made along lineages to a presumed common ancestor. Although comparisons of QTL maps among species can identify homology of QTLs by apparent co- location, lineage-specific mapping of QTL can classify homology into (1) orthology (shared origin of QTL) versus (2) paralogy (independent origin of QTL within resolution of map distance). In this light, we present a graphical method that identifies six modes of QTL evolution in a three taxon comparison. We then apply our model to map lineage-specific QTLs for inbreeding among three taxa of yellow monkey-flower: Mimulus guttatus and two inbreeders M. platycalyx and M. micranthus, but critically assuming outcrossing was the ancestral state. The two most common modes of homology across traits were orthologous (shared ancestry of mutation for QTL alleles). The outbreeder M. guttatus had the fewest lineage-specific QTL, in accordance with the presumed ancestry of outbreeding. Extensions of lineage-specific QTL mapping to other types of data and crosses, and to inference of ancestral QTL state, are discussed. Heredity (2013) 111, 106–113; doi:10.1038/hdy.2013.24; published online 24 April 2013 Keywords: Quantitative trait locus mapping; evolution of mating systems; Mimulus INTRODUCTION common ancestor of these two taxa, back to the common ancestor of Knowledge of the genetic architecture of complex traits can offer all three taxa and forwards again to the third taxon. -

Pleiotropic Scaling and QTL Data Arising From: G

NATURE | Vol 456 | 4 December 2008 BRIEF COMMUNICATIONS ARISING Pleiotropic scaling and QTL data Arising from: G. P. Wagner et al. Nature 452, 470–473 (2008) Wagner et al.1 have recently introduced much-needed data to the debate on how complexity of the genotype–phenotype map affects the distribution of mutational effects. They used quantitative trait loci (QTLs) mapping analysis of 70 skeletal characters in mice2 and regressed the total QTL effect on the number of traits affected (level of pleiotropy). From their results they suggest that mutations with higher pleiotropy have a larger effect, on average, on each of the T affected traits—a surprising finding that contradicts previous models3–7. We argue that the possibility of some QTL regions con- taining multiple mutations, which was not considered by the authors, introduces a bias that can explain the discrepancy between one of the previously suggested models and the new data. Wagner et al.1 define the total QTL effect as vffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi u uXN 10 20 30 ~t 2 T Ai N i~1 Figure 1 | Impact of multiple mutations on the total QTL effect, T. For all where N measures pleiotropy (number of traits) and Ai the normal- mutations, strict scaling according to the Euclidean superposition model is ized effect on the ith trait. They compare an empirical regression of T assumed. Black filled circles, single-mutation QTLs. Open circles, QTLs with on N with predictions from two models for pleiotropic scaling. The two mutations that affect non-overlapping traits. Red filled circles, total Euclidean superposition model3,4 assumes that the effect of a muta- effects of double-mutant QTL with overlapping trait ranges (see Methods). -

Cognitive Ability and Education: How Behavioural Genetic Research Has Advanced Our Knowledge and Understanding of Their Association

Cognitive ability and education: how behavioural genetic research has advanced our knowledge and understanding of their association Margherita Malanchini1,2,3, Kaili Rimfeld2, Andrea G. Allegrini2, Stuart J. Ritchie2, & Robert Plomin2 1 Department of Biological and Experimental Psychology, Queen Mary University of London, United Kingdom. 2 Social, Genetic and Developmental Psychiatry Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, United Kingdom. 3 Population Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin, United States. Correspondence: Margherita Malanchini, Department of Biological and Experimental Psychology, Queen Mary University of London, Office 2.02, G.E. Fogg Building, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Cognitive ability and educational success predict positive outcomes across the lifespan, from higher earnings to better health and longevity. The shared positive outcomes associated with cognitive ability and education are emblematic of the strong interconnections between them. Part of the observed associations between cognitive ability and education, as well as their links with wealth, morbidity and mortality, are rooted in genetic variation. The current review evaluates the contribution of decades of behavioural genetic research to our knowledge and understanding of the biological and environmental basis of the association between cognitive ability and education. The evidence reviewed points to a strong genetic basis in their association, observed from middle childhood to old age, which is amplified by environmental experiences. In addition, the strong stability and heritability of educational success are not driven entirely by cognitive ability. This highlights the contribution of other educationally relevant noncognitive characteristics. Considering both cognitive and noncognitive skills as well as their biological and environmental underpinnings will be fundamental in moving towards a comprehensive, evidence-based model of education. -

1 ROBERT PLOMIN on Behavioral Genetics Genetic Links Common

Genetic links • Background – Why has educational psychology ben so slow ROBERT PLOMIN to accept genetics? on Behavioral Genetics • Beyond nature vs. nurture – 3 findings from genetic research with far- reaching implications for education: October, 2004 The nature of nurture The abnormal is normal Generalist genes • Molecular Genetics Quantitative genetics: twin and adoption studies Common medical disorders Identical twins Fraternal twins (monozygotic, MZ) (dizygotic, DZ) 1 Twin concordances in TEDS at 7 years Twins Early Development Study (TEDS) for low reading and maths Perceptions of nature/nurture: % parents (N=1340) and teachers Beyond nature vs. nurture: (N=667) indicating that genes are at least as important as environment (Walker & Plomin, Ed. Psych., in press) The nature of nurture • Genetic influence on experience • Genotype-environment correlation – Children’s genetic propensities are correlated with their experiences passive evocative active 2 Beyond nature vs. nurture: Genotype-environment correlation The nature of nurture • Passive • Genotype-environment correlation – e.g., family background (SES) and school – Children’s genetic propensities are correlated with achievement their experiences passive • Evocative evocative – Children evoke experiences for genetic reasons Active • Active • Molecular genetics – Children actively create environments that foster – Find genes associated with learning experiences their genetic propensities Beyond nature vs. nurture: The one-gene one-disability (OGOD) model The abnormal is normal • Common learning disabilities are the quantitative extreme of the same genetic and environmental factors responsible for normal variation in learning abilities. • There are no common learning disabilities, just the extremes of normal variation. 3 OGOD (rare) and QTL (common) disorders The quantitative trait locus (QTL) model Beyond nature vs. -

Epigenome-Wide Study Identified Methylation Sites Associated With

nutrients Article Epigenome-Wide Study Identified Methylation Sites Associated with the Risk of Obesity Majid Nikpay 1,*, Sepehr Ravati 2, Robert Dent 3 and Ruth McPherson 1,4,* 1 Ruddy Canadian Cardiovascular Genetics Centre, University of Ottawa Heart Institute, 40 Ruskin St–H4208, Ottawa, ON K1Y 4W7, Canada 2 Plastenor Technologies Company, Montreal, QC H2P 2G4, Canada; [email protected] 3 Department of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, University of Ottawa, the Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, ON K1Y 4E9, Canada; [email protected] 4 Atherogenomics Laboratory, University of Ottawa Heart Institute, Ottawa, ON K1Y 4W7, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.N.); [email protected] (R.M.) Abstract: Here, we performed a genome-wide search for methylation sites that contribute to the risk of obesity. We integrated methylation quantitative trait locus (mQTL) data with BMI GWAS information through a SNP-based multiomics approach to identify genomic regions where mQTLs for a methylation site co-localize with obesity risk SNPs. We then tested whether the identified site contributed to BMI through Mendelian randomization. We identified multiple methylation sites causally contributing to the risk of obesity. We validated these findings through a replication stage. By integrating expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) data, we noted that lower methylation at cg21178254 site upstream of CCNL1 contributes to obesity by increasing the expression of this gene. Higher methylation at cg02814054 increases the risk of obesity by lowering the expression of MAST3, whereas lower methylation at cg06028605 contributes to obesity by decreasing the expression of SLC5A11. Finally, we noted that rare variants within 2p23.3 impact obesity by making the cg01884057 Citation: Nikpay, M.; Ravati, S.; Dent, R.; McPherson, R. -

To What Extent Does the Heritability Of

1 Bonamy R. Oliver & Alison Pike University of Sussex 'To what extent does the heritability of known features of development such as intelligence limit the potential of policy that attempts to lessen intergenerational inequalities such as early intervention, social mobility, child poverty or the social class attainment gap'. In the current report, we argue that the extent to which aspects of human development are heritable has little impact on the importance of policy that aims to ameliorate the adverse effects of environmental or intergenerational inequalities. We first address common misconceptions about heritability and behavioural genetics that can lead to inappropriate assertions about research findings and their implications for policy. We then move to demonstrate our vision of what behavioural genetics can offer early intervention science and attempts to lessen intergenerational inequality. What is behavioural genetics? Behavioural genetic research uses a variety of quasi-experimental designs to understand the role of genetic and environmental influence on variation in psychological traits such as general intelligence (e.g., Deary, Johnson, & Houlihan, 2009), disruptive behaviour (e.g., Rhee, & Waldman, 2002), and well-being (e.g., Bartels, 2015). The extent to which variance in a given trait is explained by genetic variance is termed ‘heritability’, and is explained further below. Shared environmental influences refer to experiences that contribute to sibling similarity, while non- shared environmental influences refer to differences in experience that contribute to differences between siblings in a family. The most common of these research designs are twin and adoption 2 studies. The twin design compares monozygotic (MZ: ‘identical’) and dizygotic (DZ: fraternal, ‘not identical’) twin similarity for specific psychological traits. -

QUANTITATIVE TRAIT LOCUS ANALYSIS: in Several Variants (I.E., Alleles)

TECHNOLOGIES FROM THE FIELD QUANTITATIVE TRAIT LOCUS ANALYSIS: in several variants (i.e., alleles). QTL analysis allows one MULTIPLE CROSS AND HETEROGENEOUS to map, with some precision, the genomic position of STOCK MAPPING these alleles. For many researchers in the alcohol field, the break Robert Hitzemann, Ph.D.; John K. Belknap, Ph.D.; through with respect to the genetic determination of alcohol- and Shannon K. McWeeney, Ph.D. related behaviors occurred when Plomin and colleagues (1991) made the seminal observation that a specific panel of RI mice (i.e., the BXD panel) could be used to identify KEY WORDS: Genetic theory of alcohol and other drug use; genetic the physical location of (i.e., to map) QTLs for behavioral factors; environmental factors; behavioral phenotype; behavioral phenotypes. Because the phenotypes of the different strains trait; quantitative trait gene (QTG); inbred animal strains; in this panel had been determined for many alcohol- recombinant inbred (RI) mouse strains; quantitative traits; related traits, researchers could readily apply the strategy quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping; multiple cross mapping of RI–QTL mapping (Gora-Maslak et al. 1991). Although (MCM); heterogeneous stock (HS) mapping; microsatellite investigators recognized early on that this panel was not mapping; animal models extensive enough to answer all questions, the emerging data illustrated the rich genetic complexity of alcohol- related phenotypes (Belknap 1992; Plomin and McClearn ntil well into the 1990s, both preclinical and clinical 1993). research focused on finding “the” gene for human The next advance came with the development of diseases, including alcoholism. This focus was rein U microsatellite maps (Dietrich et al. -

Article the Power to Detect Quantitative Trait Loci Using

The Power to Detect Quantitative Trait Loci Using Resequenced, Experimentally Evolved Populations of Diploid, Sexual Organisms James G. Baldwin-Brown,*,1 Anthony D. Long,1 and Kevin R. Thornton1 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]. Associate editor: John Parsch Abstract A novel approach for dissecting complex traits is to experimentally evolve laboratory populations under a controlled environment shift, resequence the resulting populations, and identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and/or genomic regions highly diverged in allele frequency. To better understand the power and localization ability of such an evolve and resequence (E&R) approach, we carried out forward-in-time population genetics simulations of 1 Mb genomic regions under a large combination of experimental conditions, then attempted to detect significantly diverged SNPs. Our analysis indicates that the ability to detect differentiation between populations is primarily affected by selection coef- ficient, population size, number of replicate populations, and number of founding haplotypes. We estimate that E&R studies can detect and localize causative sites with 80% success or greater when the number of founder haplotypes is over 500, experimental populations are replicated at least 25-fold, population size is at least 1,000 diploid individuals, and the selection coefficient on the locus of interest is at least 0.1. More achievable experimental designs (less replicated, fewer founder haplotypes, smaller effective population size, and smaller selection coefficients) can have power of greater than 50% to identify a handful of SNPs of which one is likely causative. Similarly, in cases where s 0.2, less demanding experimental designs can yield high power. -

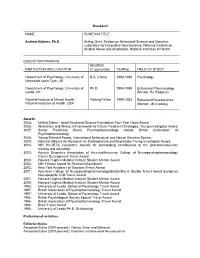

Holmes CV Current.Pdf

Biosketch NAME POSITION TITLE Andrew Holmes, Ph.D. Acting Chief, Section on Behavioral Science and Genetics, Laboratory for Integrative Neuroscience, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health EDUCATION/TRAINING DEGREE INSTITUTION AND LOCATION (if applicable) YEAR(s) FIELD OF STUDY Department of Psychology, University of B.A. (Hons) 1992-1995 Psychology Newcastle upon Tyne, UK Department of Psychology, University of Ph.D. 1995-1999 Behavioral Pharmacology Leeds, UK (Mentor, RJ Rodgers) National Institute of Mental Health, Visiting Fellow 1999-2003 Behavioral Neuroscience National Institutes of Health, USA (Mentor, JN Crawley) Awards 2008: United States - Israel Binational Science Foundation Four-Year Grant Award 2008: Alcoholism and Stress: A Framework for Future Treatment Strategies, Young Investigator Award 2007: Senior Preclinical Wyeth Psychopharmacology Award, British Association of Psychopharmacology 2006: Young Scientist Award, International Behavioural and Neural Genetics Society 2005: National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigator Award 2004: NIH Pre-IRTA Committee Awards for outstanding contributions to the post-baccalaureate training and education 2003: Anxiety Disorders Association of America/American College of Neuropsychopharmacology Career Development Travel Award 2003: Howard Hughes Medical Institute Student Mentor Award 2002: NIH Fellows Award for Research Excellence 2002: New York Academy of Sciences Travel Award 2001: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology/Bristol-Myers -

Glossary/Index

Glossary 03/08/2004 9:58 AM Page 119 GLOSSARY/INDEX The numbers after each term represent the chapter in which it first appears. additive 2 allele 2 When an allele’s contribution to the variation in a One of two or more alternative forms of a gene; a single phenotype is separately measurable; the independent allele for each gene is inherited separately from each effects of alleles “add up.” Antonym of nonadditive. parent. ADHD/ADD 6 Alzheimer’s disease 5 Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder/Attention A medical disorder causing the loss of memory, rea- Deficit Disorder. Neurobehavioral disorders character- soning, and language abilities. Protein residues called ized by an attention span or ability to concentrate that is plaques and tangles build up and interfere with brain less than expected for a person's age. With ADHD, there function. This disorder usually first appears in persons also is age-inappropriate hyperactivity, impulsive over age sixty-five. Compare to early-onset Alzheimer’s. behavior or lack of inhibition. There are several types of ADHD: a predominantly inattentive subtype, a predomi- amino acids 2 nantly hyperactive-impulsive subtype, and a combined Molecules that are combined to form proteins. subtype. The condition can be cognitive alone or both The sequence of amino acids in a protein, and hence pro- cognitive and behavioral. tein function, is determined by the genetic code. adoption study 4 amnesia 5 A type of research focused on families that include one Loss of memory, temporary or permanent, that can result or more children raised by persons other than their from brain injury, illness, or trauma. -

Holding Back the Genes: Limitations of Research Into Canine Behavioural

van Rooy et al. Canine Genetics and Epidemiology 2014, 1:7 http://www.cgejournal.org/content/1/1/7 REVIEW Open Access Holding back the genes: limitations of research into canine behavioural genetics Diane van Rooy*, Elizabeth R Arnott, Jonathan B Early, Paul McGreevy and Claire M Wade Abstract Canine behaviours that are both desirable and undesirable to owners have a demonstrable genetic component. Some behaviours are breed-specific, such as the livestock guarding by maremmas and flank sucking seen in Dobermanns. While the identification of genes responsible for common canine diseases is rapidly advancing, those genes underlying behaviours remain elusive. The challenges of accurately defining and measuring behavioural phenotypes remain an obstacle, and the use of variable phenotyping methods has prevented meta-analysis of behavioural studies. International standardised testing protocols and terminology in canine behavioural evaluations should facilitate selection against behavioural disorders in the modern dog and optimise breeding success and performance in working dogs. This review examines the common hurdles faced by researchers of behavioural genetics and the current state of knowledge. Keywords: Behaviour, Dog, Genetics, Heritability Lay summary against behavioural disorders in the dog, and optimise All canine behaviour, whether desirable or undesirable breeding success and performance in working dogs. to owners, has a genetic component. Studies of “showing This review examines the common hurdles faced by eye” and “bark” which compared the behaviour of off- researchers of behavioural genetics and the current state spring with parents concluded that behaviour does not of knowledge. follow simple Mendelian inheritance. Some behaviours are breed-specific, such as “livestock guarding” by mar- Introduction emmas and “flank sucking” seen in Dobermanns. -

Genetics and Human Behaviour

Cover final A/W13657 19/9/02 11:52 am Page 1 Genetics and human behaviour : Genetic screening: ethical issues Published December 1993 the ethical context Human tissue: ethical and legal issues Published April 1995 Animal-to-human transplants: the ethics of xenotransplantation Published March 1996 Mental disorders and genetics: the ethical context Published September 1998 Genetically modified crops: the ethical and social issues Published May 1999 The ethics of clinical research in developing countries: a discussion paper Published October 1999 Stem cell therapy: the ethical issues – a discussion paper Published April 2000 The ethics of research related to healthcare in developing countries Published April 2002 Council on Bioethics Nuffield The ethics of patenting DNA: a discussion paper Published July 2002 Genetics and human behaviour the ethical context Published by Nuffield Council on Bioethics 28 Bedford Square London WC1B 3JS Telephone: 020 7681 9619 Fax: 020 7637 1712 Internet: www.nuffieldbioethics.org Cover final A/W13657 19/9/02 11:52 am Page 2 Published by Nuffield Council on Bioethics 28 Bedford Square London WC1B 3JS Telephone: 020 7681 9619 Fax: 020 7637 1712 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.nuffieldbioethics.org ISBN 1 904384 03 X October 2002 Price £3.00 inc p + p (both national and international) Please send cheque in sterling with order payable to Nuffield Foundation © Nuffield Council on Bioethics 2002 All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, no part of the publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, or by any means, without prior permission of the copyright owners.