The Nature and Significance of Behavioural Genetic Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cognitive Ability and Education: How Behavioural Genetic Research Has Advanced Our Knowledge and Understanding of Their Association

Cognitive ability and education: how behavioural genetic research has advanced our knowledge and understanding of their association Margherita Malanchini1,2,3, Kaili Rimfeld2, Andrea G. Allegrini2, Stuart J. Ritchie2, & Robert Plomin2 1 Department of Biological and Experimental Psychology, Queen Mary University of London, United Kingdom. 2 Social, Genetic and Developmental Psychiatry Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, United Kingdom. 3 Population Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin, United States. Correspondence: Margherita Malanchini, Department of Biological and Experimental Psychology, Queen Mary University of London, Office 2.02, G.E. Fogg Building, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Cognitive ability and educational success predict positive outcomes across the lifespan, from higher earnings to better health and longevity. The shared positive outcomes associated with cognitive ability and education are emblematic of the strong interconnections between them. Part of the observed associations between cognitive ability and education, as well as their links with wealth, morbidity and mortality, are rooted in genetic variation. The current review evaluates the contribution of decades of behavioural genetic research to our knowledge and understanding of the biological and environmental basis of the association between cognitive ability and education. The evidence reviewed points to a strong genetic basis in their association, observed from middle childhood to old age, which is amplified by environmental experiences. In addition, the strong stability and heritability of educational success are not driven entirely by cognitive ability. This highlights the contribution of other educationally relevant noncognitive characteristics. Considering both cognitive and noncognitive skills as well as their biological and environmental underpinnings will be fundamental in moving towards a comprehensive, evidence-based model of education. -

Genotype, Phenotype and Cancer: Role of Low Penetrance Genes and Environment in Tumour Susceptibility

Genotype, phenotype and cancer: Role of low penetrance genes and environment in tumour susceptibility † ASHWIN KOTNIS, RAJIV SARIN and RITA MULHERKAR* Genetic Engineering, ACTREC, Tata Memorial Centre, Kharghar, Navi Mumbai 410 208, India †Tata Memorial Hospital, Parel, Mumbai 400 012, India *Corresponding author (Fax, 91-22-27412892; Email, [email protected]) Role of heredity and lifestyle in sporadic cancers is well documented. Here we focus on the influence of low penetrance genes and habits, with emphasis on tobacco habit in causing head and neck cancers. Role of such gene-environment interaction can be well studied in individuals with multiple primary cancers. Thus such a bio- logical model may elucidate that cancer causation is not solely due to genetic determinism but also significantly relies on lifestyle of the individual. [Kotnis A, Sarin R and Mulherkar R 2005 Genotype, phenotype and cancer: Role of low penetrance genes and environment in tumour sus- ceptibility; J. Biosci. 30 93–102] 1. Introduction are chromosomal translocations which result in fusion proteins (e.g. bcr-abl fusion protein due to translocation Cancer has been a scourge on the human population for of abl gene to bcr locus in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia) many years. Although numerous advances have been made or apposition of one gene to the regulatory region of an- in prevention, diagnosis and treatment of the disease, it other gene (e.g. RET and NTRK1 in thyroid papillary carci- still continues to torment mankind. As is widely believed, noma), resulting in giving the cell a growth advantage. cancer is the result of many genetic and epigenetic changes These chromosomal translocations are common in lym- in a population of cells as well as in the surrounding phomas, leukemias and mesenchymal tumours (Futreal stroma and blood vessels. -

Contribution of Multiple Inherited Variants to Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in a Family with 3 Affected Siblings

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Contribution of Multiple Inherited Variants to Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in a Family with 3 Affected Siblings Jasleen Dhaliwal 1 , Ying Qiao 1,2, Kristina Calli 1,2, Sally Martell 1,2, Simone Race 3,4,5, Chieko Chijiwa 1,5, Armansa Glodjo 3,5, Steven Jones 1,6 , Evica Rajcan-Separovic 2,7, Stephen W. Scherer 4 and Suzanne Lewis 1,2,5,* 1 Department of Medical Genetics, University of British Columbia (UBC), Vancouver, BC V6H 3N1, Canada; [email protected] (J.D.); [email protected] (Y.Q.); [email protected] (K.C.); [email protected] (S.M.); [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (S.J.) 2 BC Children’s Hospital, Vancouver, BC V5Z 4H4, Canada; [email protected] 3 Department of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia (UBC), Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z7, Canada; [email protected] (S.R.); [email protected] (A.G.) 4 The Centre for Applied Genomics and McLaughlin Centre, Hospital for Sick Children and University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5G 0A4, Canada; [email protected] 5 BC Children’s and Women’s Health Center, Vancouver, BC V6H 3N1, Canada 6 Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre, Vancouver, BC V5Z 4S6, Canada 7 Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of British Columbia (UBC), Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z7, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is the most common neurodevelopmental disorder in Citation: Dhaliwal, J.; Qiao, Y.; Calli, children and shows high heritability. -

To What Extent Does the Heritability Of

1 Bonamy R. Oliver & Alison Pike University of Sussex 'To what extent does the heritability of known features of development such as intelligence limit the potential of policy that attempts to lessen intergenerational inequalities such as early intervention, social mobility, child poverty or the social class attainment gap'. In the current report, we argue that the extent to which aspects of human development are heritable has little impact on the importance of policy that aims to ameliorate the adverse effects of environmental or intergenerational inequalities. We first address common misconceptions about heritability and behavioural genetics that can lead to inappropriate assertions about research findings and their implications for policy. We then move to demonstrate our vision of what behavioural genetics can offer early intervention science and attempts to lessen intergenerational inequality. What is behavioural genetics? Behavioural genetic research uses a variety of quasi-experimental designs to understand the role of genetic and environmental influence on variation in psychological traits such as general intelligence (e.g., Deary, Johnson, & Houlihan, 2009), disruptive behaviour (e.g., Rhee, & Waldman, 2002), and well-being (e.g., Bartels, 2015). The extent to which variance in a given trait is explained by genetic variance is termed ‘heritability’, and is explained further below. Shared environmental influences refer to experiences that contribute to sibling similarity, while non- shared environmental influences refer to differences in experience that contribute to differences between siblings in a family. The most common of these research designs are twin and adoption 2 studies. The twin design compares monozygotic (MZ: ‘identical’) and dizygotic (DZ: fraternal, ‘not identical’) twin similarity for specific psychological traits. -

A Curated Gene List for Reporting Results of Newborn Genomic Sequencing

© American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE A curated gene list for reporting results of newborn genomic sequencing Ozge Ceyhan-Birsoy, PhD1,2,3, Kalotina Machini, PhD1,2,3, Matthew S. Lebo, PhD1,2,3, Tim W. Yu, MD3,4,5, Pankaj B. Agrawal, MD, MMSC3,4,6, Richard B. Parad, MD, MPH3,7, Ingrid A. Holm, MD, MPH3,4, Amy McGuire, PhD8, Robert C. Green, MD, MPH3,9,10, Alan H. Beggs, PhD3,4, Heidi L. Rehm, PhD1,2,3,10; for the BabySeq Project Purpose: Genomic sequencing (GS) for newborns may enable detec- of newborn GS (nGS), and used our curated list for the first 15 new- tion of conditions for which early knowledge can improve health out- borns sequenced in this project. comes. One of the major challenges hindering its broader application Results: Here, we present our curated list for 1,514 gene–disease is the time it takes to assess the clinical relevance of detected variants associations. Overall, 954 genes met our criteria for return in nGS. and the genes they impact so that disease risk is reported appropri- This reference list eliminated manual assessment for 41% of rare vari- ately. ants identified in 15 newborns. Methods: To facilitate rapid interpretation of GS results in new- Conclusion: Our list provides a resource that can assist in guiding borns, we curated a catalog of genes with putative pediatric relevance the interpretive scope of clinical GS for newborns and potentially for their validity based on the ClinGen clinical validity classification other populations. framework criteria, age of onset, penetrance, and mode of inheri- tance through systematic evaluation of published evidence. -

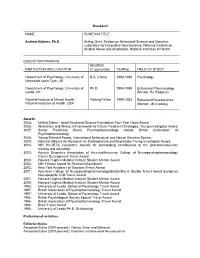

Holmes CV Current.Pdf

Biosketch NAME POSITION TITLE Andrew Holmes, Ph.D. Acting Chief, Section on Behavioral Science and Genetics, Laboratory for Integrative Neuroscience, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health EDUCATION/TRAINING DEGREE INSTITUTION AND LOCATION (if applicable) YEAR(s) FIELD OF STUDY Department of Psychology, University of B.A. (Hons) 1992-1995 Psychology Newcastle upon Tyne, UK Department of Psychology, University of Ph.D. 1995-1999 Behavioral Pharmacology Leeds, UK (Mentor, RJ Rodgers) National Institute of Mental Health, Visiting Fellow 1999-2003 Behavioral Neuroscience National Institutes of Health, USA (Mentor, JN Crawley) Awards 2008: United States - Israel Binational Science Foundation Four-Year Grant Award 2008: Alcoholism and Stress: A Framework for Future Treatment Strategies, Young Investigator Award 2007: Senior Preclinical Wyeth Psychopharmacology Award, British Association of Psychopharmacology 2006: Young Scientist Award, International Behavioural and Neural Genetics Society 2005: National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigator Award 2004: NIH Pre-IRTA Committee Awards for outstanding contributions to the post-baccalaureate training and education 2003: Anxiety Disorders Association of America/American College of Neuropsychopharmacology Career Development Travel Award 2003: Howard Hughes Medical Institute Student Mentor Award 2002: NIH Fellows Award for Research Excellence 2002: New York Academy of Sciences Travel Award 2001: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology/Bristol-Myers -

Genetic Risk Assessment and BRCA Mutation Testing for Breast and Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility: Evidence Synthesis

Evidence Synthesis Number 37 Genetic Risk Assessment and BRCA Mutation Testing for Breast and Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility: Evidence Synthesis Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 540 Gaither Road Rockville, MD 20850 www.ahrq.gov Contract No. 290-02-0024 Task Order No. 2 Technical Support of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Prepared by: Oregon Evidence-based Practice Center Portland, Oregon Investigators Heidi D. Nelson, MD, MPH Laurie Hoyt Huffman, MS Rongwei Fu, PhD Emily L. Harris, PhD, MPH Miranda Walker, BA Christina Bougatsos, BS September 2005 This report may be used, in whole or in part, as the basis of the development of clinical practice guidelines and other quality enhancement tools, or a basis for reimbursement and coverage policies. AHRQ or U.S. Department of Health and Human Services endorsement of such derivative products may not be stated or implied. AHRQ is the lead Federal agency charged with supporting research designed to improve the quality of health care, reduce its cost, address patient safety and medical errors, and broaden access to essential services. AHRQ sponsors and conducts research that provides evidence-based information on health care outcomes; quality; and cost, use, and access. The information helps health care decisionmakers—patients and clinicians, health system leaders, and policymakers—make more informed decisions and improve the quality of health care services. Preface The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) sponsors the development of Systematic Evidence Reviews (SERs) and Evidence Syntheses through its Evidence-based Practice Program. With guidance from the U.S. -

Holding Back the Genes: Limitations of Research Into Canine Behavioural

van Rooy et al. Canine Genetics and Epidemiology 2014, 1:7 http://www.cgejournal.org/content/1/1/7 REVIEW Open Access Holding back the genes: limitations of research into canine behavioural genetics Diane van Rooy*, Elizabeth R Arnott, Jonathan B Early, Paul McGreevy and Claire M Wade Abstract Canine behaviours that are both desirable and undesirable to owners have a demonstrable genetic component. Some behaviours are breed-specific, such as the livestock guarding by maremmas and flank sucking seen in Dobermanns. While the identification of genes responsible for common canine diseases is rapidly advancing, those genes underlying behaviours remain elusive. The challenges of accurately defining and measuring behavioural phenotypes remain an obstacle, and the use of variable phenotyping methods has prevented meta-analysis of behavioural studies. International standardised testing protocols and terminology in canine behavioural evaluations should facilitate selection against behavioural disorders in the modern dog and optimise breeding success and performance in working dogs. This review examines the common hurdles faced by researchers of behavioural genetics and the current state of knowledge. Keywords: Behaviour, Dog, Genetics, Heritability Lay summary against behavioural disorders in the dog, and optimise All canine behaviour, whether desirable or undesirable breeding success and performance in working dogs. to owners, has a genetic component. Studies of “showing This review examines the common hurdles faced by eye” and “bark” which compared the behaviour of off- researchers of behavioural genetics and the current state spring with parents concluded that behaviour does not of knowledge. follow simple Mendelian inheritance. Some behaviours are breed-specific, such as “livestock guarding” by mar- Introduction emmas and “flank sucking” seen in Dobermanns. -

Genetics and Human Behaviour

Cover final A/W13657 19/9/02 11:52 am Page 1 Genetics and human behaviour : Genetic screening: ethical issues Published December 1993 the ethical context Human tissue: ethical and legal issues Published April 1995 Animal-to-human transplants: the ethics of xenotransplantation Published March 1996 Mental disorders and genetics: the ethical context Published September 1998 Genetically modified crops: the ethical and social issues Published May 1999 The ethics of clinical research in developing countries: a discussion paper Published October 1999 Stem cell therapy: the ethical issues – a discussion paper Published April 2000 The ethics of research related to healthcare in developing countries Published April 2002 Council on Bioethics Nuffield The ethics of patenting DNA: a discussion paper Published July 2002 Genetics and human behaviour the ethical context Published by Nuffield Council on Bioethics 28 Bedford Square London WC1B 3JS Telephone: 020 7681 9619 Fax: 020 7637 1712 Internet: www.nuffieldbioethics.org Cover final A/W13657 19/9/02 11:52 am Page 2 Published by Nuffield Council on Bioethics 28 Bedford Square London WC1B 3JS Telephone: 020 7681 9619 Fax: 020 7637 1712 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.nuffieldbioethics.org ISBN 1 904384 03 X October 2002 Price £3.00 inc p + p (both national and international) Please send cheque in sterling with order payable to Nuffield Foundation © Nuffield Council on Bioethics 2002 All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, no part of the publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, or by any means, without prior permission of the copyright owners. -

Open Universiteit Research Portal

Adaptive and Genomic Explanations of Human Behaviour: Citation for published version (APA): Barendregt, M., & van Hezewijk, R. W. J. V. (2005). Adaptive and Genomic Explanations of Human Behaviour: Might Evolutionary Psychology Contribute to Behavioural Genomics? Biology & Philosophy, 20, 57-78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-005-0388-2 DOI: 10.1007/s10539-005-0388-2 Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2005 Document Version: Peer reviewed version Document license: CC BY-NC-ND Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Genetics and Human Behaviour: the Ethical Context a Guide to the Report

Genetics and human behaviour: the ethical context a guide to the Report Introduction Do we inherit our behaviour? Or The Nuffield Council on Bioethics does it depend on our upbringing? has published a Report, Genetics There is little doubt that genes and human behaviour: the ethical do have some influence on our context, which examines the ethical, personality. But how much? legal and social issues that Research to find out how our genes behavioural genetics raises. This influence our behaviour is complex summary sets out some of the and controversial. There are concerns arguments and recommendations both about the science itself and the which are discussed in more detail potential applications. in the Report. [Notes in square brackets throughout refer to chapters and paragraphs in the Report]. What is behavioural genetics? Research in the field of behavioural genetics aims to find out how genes influence our behaviour. Researchers are trying to identify particular genes, or groups of genes, that are associated with behavioural traits, and investigating the role of environmental factors. Scientific background The Report considers behavioural traits such What is normal? as intelligence, personality (including anxiety, novelty-seeking and shyness), antisocial behaviour We use a statistical definition of ‘normal’ to refer (including aggression and violent behaviour) and to the range of variation, usually about 95% of sexual orientation. The focus is on behaviour the population, which does not contain anyone within the normal range of variation, rather than with clinical disorders or diseases. This use of diseases or disorders. ‘normal’ does not imply any value judgement about different forms of behaviour. -

Behavioral Genetics and Neurogenetics» for 37.04.01 «Cognitive Sciences and Technologies: from Neuron to Cognition», Master of Science

National Research University Higher School of Economics Syllabus for the course «Behavioral genetics and neurogenetics» for 37.04.01 «Cognitive sciences and technologies: from neuron to cognition», Master of Science Government of Russian Federation Federal State Autonomous Educational Institution of High Education «National Research University Higher School of Economics» Faculty of Social science Department of Psychology Syllabus for the course «Behavioral genetics and neurogenetics» 37.04.01 «Cognitive sciences and technologies: from neuron to cognition», Master of Science Authors: Yulia Kovas, Ph.D in behavioral genetics, professor, Goldsmiths University of London - [email protected] And Olga V. Sysoeva, PhD of psychological sciences, Senior researcher in MEG Center, MGPPU, [email protected] Approved by Academic Council: «_29_»__августа___ 2017 г., № _51___________ Academic supervisor of the «Cognitive sciences and technologies: from neuron to cognition» Dr. Anna Shestakova __________________________ Moscow, 2017 This syllabus may not be used by other departments of the University and by any other institutions without permission of the Author. National Research University Higher School of Economics Syllabus for the course «Behavioral genetics and neurogenetics» for 37.04.01 «Cognitive sciences and technologies: from neuron to cognition», Master of Science Summary “Behavioral genetics” will promote an understanding of the current state of affairs with regards to behavioural genetics. Basic principles as well as recent developments will be explored in relation to a broad range of phenotypes. Historical and ethical issues will be discussed. The structure and function of DNA will be studied in the context of investigations into individual variation in psychological traits. Students will be introduced to behavioural genomic analysis, such as investigating gene-environment interaction, testing educational interventions, and testing the generalist genes hypotheses - using information on measured genes and measured environments.