African Herodotus”: on the Making of the New Annotated Edition of C.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conference Program

Program 49th Annual International Meeting June 27-30, 2018 Amsterdam, Netherlands Final Program Society for Psychotherapy Research 49th Annual International Meeting Amsterdam, Netherlands June 27-30, 2018 2 President Paulo P.P. Machado Past President J. Christopher Muran President Elect Mariane Krause General Vice-President Bruce Wampold Executive Officer Marna S. Barrett Regional Chapter Presidents Latin America Fernanda Serralta United Kingdom Felicitas Rost North America Shelley McMain Europe Stig Poulsen Program Planning Committee Mariane Krause (Program Chair), Jack Dekker (Local Host), Carolina Altimir, Paulina Barros, Claudia Capella, Marcelo Cárcamo, Louis Castonguay, Paula Dagnino, Kim de Jong, Gary Diamond, Ulrike Dinger, Daniel Espinosa, Fredrik Falkenström, Shigeru Iwakabe, Clara Hill, Claudio Martínez, Shelley McMain, Nick Migdley, Mahaira Reinel, Nelson Valdés, Daniel Vásquez, Sigal Zilcha-Mano. Local Organizing Committee Jack Dekker (Chair Local Organizing Committee), Kim de Jong. Web & IT Sven Schneider Meetingsavvy.com Brad Smith Copyright @ 2018 Society for Psychotherapy Research www.psychotherapyresearch.org 3 Preface Dear Colleagues, The members of the Conference Program Planning Committee and Local Organizing Committee warmly welcome you to Amsterdam for the 49th International Meeting of the Society for Psychotherapy Research. Amsterdam is known worldwide for being a diverse, open, and tolerant city that combines a strong culture with modern and sustainable development. In keeping with our host city, the theme for SPR’s 49th Annual International meeting is "Integrating Diversity into Psychotherapy Research". As part of our commitment to making our society even more inclusive and international, diversity gives us the chance to foster integration and inclusion while at the same time enriching our discipline. The program of this new version of our annual meeting reflects this diversity. -

Hrudní Endovaskulární Graft Zenith Alpha™ Návod K Použití

MEDICAL EN Zenith Alpha™ Thoracic Endovascular Graft 15 Instructions for Use CS Hrudní endovaskulární graft Zenith Alpha™ 22 Návod k použití DA Zenith Alpha™ torakal endovaskulær protese 29 Brugsanvisning DE Zenith Alpha™ thorakale endovaskuläre Prothese 36 Gebrauchsanweisung EL Θωρακικό ενδαγγειακό μόσχευμα Zenith Alpha™ 44 Οδηγίες χρήσης ES Endoprótesis vascular torácica Zenith Alpha™ 52 Instrucciones de uso FR Endoprothèse vasculaire thoracique Zenith Alpha™ 60 Mode d’emploi HU Zenith Alpha™ mellkasi endovaszkuláris graft 67 Használati utasítás IT Protesi endovascolare toracica Zenith Alpha™ 74 Istruzioni per l’uso NL Zenith Alpha™ thoracale endovasculaire prothese 81 Gebruiksaanwijzing NO Zenith Alpha™ torakalt endovaskulært implantat 88 Bruksanvisning PL Piersiowy stent-graft wewnątrznaczyniowy Zenith Alpha™ 95 Instrukcja użycia PT Prótese endovascular torácica Zenith Alpha™ 103 Instruções de utilização SV Zenith Alpha™ endovaskulärt graft för thorax 110 Bruksanvisning Patient I.D. Card Included I-ALPHA-TAA-1306-436-01 *436-01* ENGLISH ČESKY TABLE OF COntents OBSAH 1 DEVICE DESCRIPTION ....................................................................... 15 1 POPIS ZAŘÍZENÍ ....................................................................................... 22 1.1 Zenith Alpha Thoracic Endovascular Graft .........................................15 1.1 Hrudní endovaskulární graft Zenith Alpha .............................................. 22 1.2 Introduction System ...................................................................................15 -

Religion, Mission and National Development

Page 1 of 6 Original Research Religion, mission and national development: A contextual interpretation of Jeremiah 29:4–7 in the light of the activities of the Basel Mission Society in Ghana (1828–1918) and its missiological implications Author: We cannot realistically analyse national development without factoring religion into the analysis. 1 Peter White In the same way, we cannot design any economic development plan without acknowledging Affiliation: the influence of religion on its implementation. The fact is that, many economic development 1Department of Science of policies require a change from old values, attitudes, beliefs and behaviour patterns of the Religion and Missiology, citizenry to those that are supportive of the new policy. Christianity has become a potent social University of Pretoria, force in every facet of Ghanaian life, from family life, economic activities, occupation, and South Africa health to education. In the light of the essential role of religion in national development, this Correspondence to: article discusses the role the Basel Mission Society played in the development of Ghana and Peter White its missiological implications. This article argues that the Basel Mission Society did not only present the gospel to the people of Ghana, they also practicalised the gospel by developing Email: [email protected] their converts spiritually, economically, and educationally. Through these acts of love by the Basel Mission Society, the spreading of the Gospel gathered momentum and advanced. Postal address: Private Bag X20, Hatfield Intradisciplinary and/or interdisciplinary implications: The article contributes to the 0028, South Africa interdisciplinary discourse on religion and development with specific reference to the role of the Basel Mission Society’s activities in Ghana (1828–1918). -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Vergesset Asante nicht!“ Der Beitrag des Basler Missionars Friedrich August Louis Ramseyer zur Asante Mission 1864–1896 Verfasserin Manuela Koncz angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, Mai 2011 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 390 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Afrikawissenschaften Betreuer: Mag. Dr. Clemens Gütl EIDESSTATTLICHE ERKLÄRUNG Ich erkläre an Eides statt, dass ich die vorliegende Diplomarbeit selbständig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst, andere als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel nicht benutzt und die den benutzten Quellen wörtlich und inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche erkenntlich gemacht habe. Wien, Mai 2011 Koncz Manuela II Danksagung Mein Dank richtet sich naturgemäß an all Jene, die in aufopferungsvoller Hingabe meine Launen während des Entstehungsprozesses der vorliegenden Arbeit geduldig ertragen haben. Ihre fortwährende Motivation und Aufmunterung waren mir in Zeiten von Stagnation und Rückschlägen stets ein Ansporn und haben somit maßgeblich zur Fertigstellung beigetragen. Hier soll allen voran meine Studienkollegin Mazza genannt sein, mit welcher mich seit Beginn des Studiums eine tiefe Freundschaft verbindet und die es durch ihr schier grenzenloses Verständnis geschafft hat, mich aus so manchem Sumpf zu ziehen. Besonderer Dank gebührt meinem Diplomarbeitsbetreuer Mag. Dr. Clemens Gütl, der es vermochte mich schon mit seiner ersten Lehrveranstaltung in den Bann von Missionsgeschichte zu ziehen. Seine konstruktive wie faire Kritik, sowie seine Ratschläge abseits der Erstellung dieser Arbeit, waren mir eine außerordentliche Hilfe. Gleichsam sei hier Herrn Dr. Guy Thomas, Leiter des Archives der mission21 in Basel, sowie seinem gesamten Team gedankt, welche mir während meiner Archivforschung in Basel alle erdenkliche Hilfe haben zukommen lassen. Für ihre fortwährende Unterstützung während der Jahre meines Studiums, möchte ich meinen Dank an Putzla und Hans aussprechen, welche mich so freundlich und liebevoll aufgenommen haben. -

Some Translation and Exegetical Problems in the Pastoral Epistles of the Kronkron (Akuapem-Twi Bible) By

Some Translation and Exegetical Problems in the Pastoral Epistles of the kronkron (Akuapem-Twi Bible) By Emmanuel Augustus Twum-Baah July 2014 Some Translation and Exegetical Problems in the Pastoral Epistles of the kronkron (Akuapem-Twi Bible) A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Award of Master of Philosophy Degree in Religious Studies By Emmanuel Augustus Twum-Baah July 2014 i Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis of which is a record is the result of my own work and that no part of it has been presented for another degree in this university or elsewhere, and that all sources of information used have been duly referenced by way of footnotes. Emmanuel Augustus Twum-Baah …………………… ...………………………. (Student) Signature Date Certified by: Rev. Jonathan E. T. Kuwornu-Adjaottor …………………… ......………………………. (Supervisor) Signature Date Certified by: Rev. Dr. Nathan Iddrisu Samwini …………………… ........….……………………. (Head of Department) Signature Date ii Abstract The present 2012 Akuapem-Twi Bible had been the labour of several revision exercises from its existence as fragments of Bible books till the New Testament was completed and later the first full version published in 1871. Over the years the task of revision work had aimed at eliminating ambiguous phrases and words in the Akuapem-Twi Bible that are not translated in accordance with the thought pattern and worldview of the Akuapem people. However after the 2012 publication of the Akuapem-Twi Bible, there still exist a number of translation and exegetical problems in the translated text; clear examples are 1 Timothy 6:10a, 2 Timothy 1: 10b, 2:20b, Titus 1: 7, 11b which are in focus for this study. -

The Impact of Basel Mission Ideology on the Thought of Carl Christian Reindorf Heinz Hauser-Renner

“Obstinate” Pastor and Pioneer Historian: The Impact of Basel Mission Ideology on the Thought of Carl Christian Reindorf Heinz Hauser-Renner n 1895, after twenty-five years of historical and ethnological Reindorf’s Western Education Iresearch, Carl Christian Reindorf, a Ghanaian pastor of the Basel Mission, produced a massive and systematic work about Reindorf’s Western education consisted of five years’ attendance the people of modern southern Ghana, The History of the Gold at the Danish castle school at Fort Christiansborg (1842–47), close Coast and Asante (1895).1 Reindorf, “the first African to publish to Osu in the greater Accra area, and another six years’ training at a full-length Western-style history of a region of Africa,”2 was the newly founded Basel Mission school at Osu (1847–55), minus a born in 1834 at Prampram/Gbugblã, Ghana, and he died in 1917 two-year break working as a trader for one of his uncles (1850–52). at Osu, Ghana.3 He was in the service of the Basel Mission as a At the Danish castle school Reindorf was taught the catechism and catechist and teacher, and later as a pastor until his retirement in arithmetic in Danish. Basel missionary Elias Schrenk later noted 1893; but he was also known as an herbalist, farmer, and medi- that the boys did not understand much Danish and therefore did cal officer as well as an intellectual and a pioneer historian. The not learn much, and he also observed that Christian principles intellectual history of the Gold Coast, like that of much of Africa, were not strictly followed, as the children were even allowed to is yet to be thoroughly studied. -

The Slow Death of Slavery in Nineteenth Century Senegal and the Gold Coast

That Most Perfidious Institution: The slow death of slavery in nineteenth century Senegal and the Gold Coast Trevor Russell Getz Submitted for the degree of PhD University of London, School or Oriental and African Studies ProQuest Number: 10673252 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673252 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract That Most Perfidious Institution is a study of Africans - slaves and slave owners - and their central roles in both the expansion of slavery in the early nineteenth century and attempts to reform servile relationships in the late nineteenth century. The pivotal place of Africans can be seen in the interaction between indigenous slave-owning elites (aristocrats and urban Euro-African merchants), local European administrators, and slaves themselves. My approach to this problematic is both chronologically and geographically comparative. The central comparison between Senegal and the Gold Coast contrasts the varying impact of colonial policies, integration into the trans-Atlantic economy; and, more importantly, the continuity of indigenous institutions and the transformative agency of indigenous actors. -

The Evolution of Christianity and German Slaveholding in Eweland, 1847-1914 by John Gregory

“Children of the Chain and Rod”: The Evolution of Christianity and German Slaveholding in Eweland, 1847-1914 by John Gregory Garratt B.A. in History, May 2009, Elon University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2017 Andrew Zimmerman Professor of History and International Affairs The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that John Gregory Garratt has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of December 9, 2016. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “Children of the Chain and Rod”: The Evolution of Christianity and German Slaveholding in Eweland, 1847-1914 John Gregory Garratt Dissertation Research Committee: Andrew Zimmerman, Professor of History and International Affairs, Dissertation Director Dane Kennedy, Elmer Louis Kayser Professor of History and International Affairs, Committee Member Nemata Blyden, Associate Professor of History and International Affairs, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2017 by John Garratt All rights reserved iii Acknowledgments The completion of this dissertation is a testament to my dissertation director, Andrew Zimmerman. His affability made the academic journey from B.A. to Ph.D more enjoyable than it should have been. Moreover, his encouragement and advice proved instrumental during the writing process. I would also like to thank my dissertation committee. Dane Kennedy offered much needed writing advice in addition to marshalling his considerable expertise in British history. Nemata Blyden supported my tentative endeavors in African history and proffered early criticism to frame the dissertation. -

Select Bibliography

Select Bibliography by the late F. Seymour-Smith Reference books and other standard sources of literary information; with a selection of national historical and critical surveys, excluding monographs on individual authors (other than series) and anthologies. Imprint: the place of publication other than London is stated, followed by the date of the last edition traced up to 1984. OUP- Oxford University Press, and includes depart mental Oxford imprints such as Clarendon Press and the London OUP. But Oxford books originating outside Britain, e.g. Australia, New York, are so indicated. CUP - Cambridge University Press. General and European (An enlarged and updated edition of Lexicon tkr WeltliU!-atur im 20 ]ahrhuntkrt. Infra.), rev. 1981. Baker, Ernest A: A Guilk to the B6st Fiction. Ford, Ford Madox: The March of LiU!-ature. Routledge, 1932, rev. 1940. Allen and Unwin, 1939. Beer, Johannes: Dn Romanfohrn. 14 vols. Frauwallner, E. and others (eds): Die Welt Stuttgart, Anton Hiersemann, 1950-69. LiU!-alur. 3 vols. Vienna, 1951-4. Supplement Benet, William Rose: The R6athr's Encyc/opludia. (A· F), 1968. Harrap, 1955. Freedman, Ralph: The Lyrical Novel: studies in Bompiani, Valentino: Di.cionario letU!-ario Hnmann Hesse, Andrl Gilk and Virginia Woolf Bompiani dille opn-e 6 tUi personaggi di tutti i Princeton; OUP, 1963. tnnpi 6 di tutu le let16ratur6. 9 vols (including Grigson, Geoffrey (ed.): The Concise Encyclopadia index vol.). Milan, Bompiani, 1947-50. Ap of Motkm World LiU!-ature. Hutchinson, 1970. pendic6. 2 vols. 1964-6. Hargreaves-Mawdsley, W .N .: Everyman's Dic Chambn's Biographical Dictionary. Chambers, tionary of European WriU!-s. -

2016-06-16 Report Team Visit Ghana 2015 Final

EMS “Mission Moves” Team Visit I Presbyterian Church of Ghana (PCG) / September 2015 “Mission Moves”: Akwaaba! Eye me anigyie se ma ba Ghana. [Welcome! I am glad to be in Ghana.] Team Visit to Ghana as a common journey of discovering mission history, discussing the understanding of mission today and reflecting upon mission challenges for tomorrow. Table of Contents: 1. Introduction: The Team Visit Concept . Page 2 2. The Character of our Team and the Participants . Page 3 3. Mission starts with “A” like Abokobi, Abetifi, Akropong, Akuapem: Itinerary . Page 4 4. Motivation for the Team Visit and Understanding of Mission . Page 7 5. The PCG - A Tanker of Faith with Deep Roots in the Whole Country. Page 10 6. Addressing the Questions. Discovering the challenges for today . Page 11 7. Word of Thanks . Page 25 8. Appendix I: A Short Mission History Written by Strangers and Lay People . Page 26 9. Appendix II Final Questions for our Evaluation . Page 38 „Mission Moves“ Team Visit I / PCG EMS “Mission Moves” Team Visit I Presbyterian Church of Ghana (PCG) Page 1 of 43 Sunday 20 th of September 2015 Thanksgiving Service at the Osu Ebenezer Congregation in Osu (Accra) celebrating 200 years of Basel Mission. From right: Emmanuel Tettey (Ghana) Rev. Lee, JungGon (Korea), Clement Sam-Dadjie(Ghana), Friederike Faller (Germany, Berlin), Zillah Odjelua, Schulamit Kriener (Germany / German East-Asia Mission / London, GB),Rev. Heike Bosien (Germany, Stuttgart), Ms. Philipa Odjelua, Rev. Samuel Odjelua, Aphiwe Mpeka (South Africa), Rev. Asao Mochizuki (Japan), Rahel Anne Römer (Germany, Mannheim). 1. Introduction: The Element of Strangeness and the View of Unprejudiced People rather than that of Ghana-Experts. -

Uncovering Multiple Conversion Avenues for Effective Evangelism Tim Buechsel George Fox University

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Doctor of Ministry Seminary 1-1-2013 One size fits all? uncovering multiple conversion avenues for effective evangelism Tim Buechsel George Fox University This research is a product of the Doctor of Ministry (DMin) program at George Fox University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Buechsel, Tim, "One size fits all? uncovering multiple conversion avenues for effective evangelism" (2013). Doctor of Ministry. Paper 44. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dmin/44 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Seminary at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY ONE SIZE FITS ALL? UNCOVERING MULTIPLE CONVERSION AVENUES FOR EFFECTIVE EVANGELISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO GEORGE FOX EVANGELICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY TIM BUECHSEL PORTLAND, OREGON MARCH 2013 George Fox Evangelical Seminary George Fox University Portland, Oregon CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ________________________________ DMin Dissertation ________________________________ This is to certify that the DMin Dissertation of Tim Buechsel has been approved by the Dissertation Committee on March 14, 2013 for the degree of Doctor of Ministry in Leadership and Global Perspectives. Dissertation Committee: Primary Advisor: Clifford Berger, DMin Secondary Advisor: Roger Helland, DMin Lead Mentor: Jason Clark, DMin Copyright -

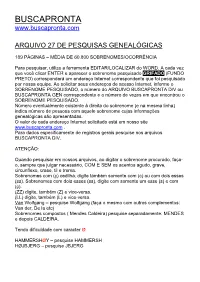

Adams Adkinson Aeschlimann Aisslinger Akkermann

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 27 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 189 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 60.800 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA.