Make It Old: Hollis Frampton Contra Ezra Pound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-10803-5 - Modernism and Homer: The Odysseys of H.D., James Joyce, Osip Mandelstam, and Ezra Pound Leah Culligan Flack Index More information Index “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste” Classics (1912), 3 and pedantry, 132, 193 Abyssinia crisis, 140–1 decline in the study of, 13, 133 Acmeism, 15, 59, 70 Coburn, Alvin Langdon, 157 Adams, John, 2, 128, 130–1, 142–3, 153 Crisis in the humanities, 19, 206 Aeneid. See Virgil Aeschylus, 165–6, 173 d’Este, Niccolo, 53 Akhmatova, Anna, 15, 59, 63, 78, 82, 88 Dante, 37, 50, 69, 93, 157 Anderson, Margaret, 100 Dickinson, Emily, 190 Apollinaire, Guillaume, 197 Divus, Andreas (Justinopolitanus), 14, 25, 36–43, Arnold, Matthew, 10, 136, 166 50, 154 Atwood, Margaret, 203 Dörpfeld, Wilhelm, 11 Austin, Norman, 177 Downes, Jeremy, 180 DuPlessis, Rachel Blau, 9, 162 Balfour, Arthur James, 140 Barnhisel, Gregory, 8, 128, 158–9 Ehrenburg, Ilya, 78 Barthes, Roland, 79–80 Eliot, T. S., 4, 6, 28, 95, 151, 159, 162, 165–6, 181 Bate, W. Jackson, 21 mythic method, 8 Beecroft, Alexander, 180 The Waste Land, 16, 42, 47, 165, 195, 199 Benjamin, Walter, 196 Ellison, Ralph Bérard, Victor, 15, 99, 103 Invisible Man, 201–2 Bethea, David, 13, 60 Ellmann, Richard, 96, 107, 114, 197 Bishop, Elizabeth, 160–1 Emerson, Ralph Waldo, 29, 190 Brodsky, Joseph, 200 Emmet, Robert, 108, 115 Brooke, Rupert, 1 epic, 164, 180, 186, See also Pound, Ezra and epic; Brown, Clarence, 93 Mandelstam, Osip and epic; and H.D. Brown, Richard, 95 and epic Budgen, Frank, 104 epic vs. -

A Poem Containing History": Pound As a Poet of Deep Time Newell Scott Orp Ter Brigham Young University

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive All Theses and Dissertations 2017-03-01 "A poem containing history": Pound as a Poet of Deep Time Newell Scott orP ter Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Porter, Newell Scott, ""A poem containing history": Pound as a Poet of Deep Time" (2017). All Theses and Dissertations. 6326. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6326 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “A poem containing history”: Pound as a Poet of Deep Time Newell Scott Porter A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Edward Cutler, Chair Jarica Watts John Talbot Department of English Brigham Young University Copyright © 2017 Newell Scott Porter All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT “A poem containing history”: Pound as a Poet of Deep Time Newell Scott Porter Department of English, BYU Master of Arts There has been an emergent trend in literary studies that challenges the tendency to categorize our approach to literature. This new investment in the idea of “world literature,” while exciting, is also both theoretically and pragmatically problematic. While theorists can usually articulate a defense of a wider approach to literature, they struggle to develop a tangible approach to such an ideal. -

At Last, the Real Distinguished Thing at Last, the Real Distinguished Thing

at last, The Real Distinguished Thing at last, The Real Distinguished Thing The Late Poems of Eliot, Pound, Stevens, and Williams by Kathleen Woodward OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Excerpts from Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot are reprinted by permission of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., and Faberand Faber, Ltd.; copyright 1943 by T. S. Eliot; copyright 1971 by Esme Valerie Eliot. Excerpts from the following works are reprinted by permission of New Directions, New York, and Faber and Faber, Ltd., London: The Cantos ofEzra Pound, copyright 1948 by Ezra Pound; Pavannes and Divagations by Ezra Pound, copyright © 1958 by Ezra Pound, all rights reserved. Excerpts from The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens are reprinted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and Faber and Faber, Ltd.; copyright © 1923, 1931, 1935, 1936, 1937, 1942, 1943, 1944, 1945, 1946, 1947, 1948, 1949, 1950, 1951, 1952, 1954 by Wallace Stevens. Excerpts from the following works by William Carlos Williams are reprinted by permission of New Directions: Paterson, copyright 1946, 1949, 1951, 1958 by William Carlos Wil liams; Pictures from Brueghel and Other Poems, copyright 1954 by William Carlos Williams; Selected Essays, copyright 1954 by William Carlos Williams; / Wanted to Write a Poem, edited by Edith Heal, copyright © 1958 by William Carlos Williams. Chapter 1 originally appeared in different form as "Master Songs of Meditation: The Late Poems of Eliot, Pound, Stevens, and Williams," in Aging and the Elderly: Humanistic Perspectives in Gerontology, edited by Stuart F. Spicker, Kathleen Woodward, and David D. Van Tassel (Humanities Press, 1978), and is reprinted by permission of Humanities Press, Inc., Atlantic Highlands, N.J. -

20Th Anniversary Issue Fall 2009 GUEST EDITORS for 2Oth Anniversary Issue H

Shawangunk Review State University of New York at New Paltz New Paltz, New York 20th Anniversary Issue Fall 2009 GUEST EDITORS for 2oth Anniversary Issue H. R. Stoneback Joann K. Deiudicibus Dennis Doherty REVIEW EDITORS Daniel Kempton H. R. Stoneback Cover art: Jason Cring The Shawangunk Review is the journal of the English Graduate Program at the State University of New York, New Paltz. TheReview publishes the proceedings of the annual English Graduate Symposium and literary articles by graduate students as well as poetry and book reviews by students and faculty. The views expressed in the Shawangunk Review are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of English at SUNY New Paltz. Please address correspondence to Shawangunk Review, Department of English, SUNY New Paltz, New Paltz, NY 12561. Copyright © 2009 Department of English, SUNY New Paltz. All rights reserved. Contents From the Editors 1 No Lady of Shallot William Bedford Clark 3 Preventive Grace William Bedford Clark 4 Yellow House Pauline Uchmanowicz 5 Reader to the Page Pauline Uchmanowicz 6 It Is Marvelous To Sleep Together Joann K. Deiudicibus 7 I Have an Obligation to Chaos Joann K. Deiudicibus 8 Prodigal James Sherwood 10 Now: Light Rain and Freezing Rain and 32°F James Sherwood 11 Pedagogical Dilemma #1 Christopher Tanis On “Rereading Whitman” (and Pound) 13 Editorial Note 15 Rereading Whitman Mary de Rachewiltz 16 Song and Letter to be Delivered to Brunnenburg Castle H. R. Stoneback 18 The Shifty Night William Boyle 19 Micel biþ se Meotudes egsa Daniel Kempton 20 The Enormous Tragedy of the Dream Brad McDuffie (“On Christ’s Bent Shoulders”) 22 The Poet Did Not Answer Matthew Nickel 24 Buying Pound’s Cantos Alex Andriesse Shakespeare 27 Mothers and Sons William Boyle 29 Father Kafka His Long Lost Helmet Lynn Behrendt 30 If This is New Jersey Lynn Behrendt 32 July 15, 2002: A Meditation on My Last Tour de France H .R. -

Ezra Pound and the Rhetoric of Address

PETER NICHOLLS Ezra Pound and the Rhetoric of Address Ezra Pound’s repudiation of “rhetoric” constituted one of the principal strands in early modernism’s attempt to define itself against the literary values of the nineteenth century. For Pound, Victorianism represented a culture of “the opalescent word, the rhetorical tradition”;1 in “A Retrospect” (published in 1918), he called famously for a “harder and saner” poetry, one freed from the previous century’s “rhetorical din, and luxurious riot,” “austere, direct, free from emotional slither.”2 Yet even as he argued for this “harder and saner” poetry Pound also discerned a dimension of poetry precisely as being in excess of directly communicable meaning. When his theorizing took a self-consciously “modern” turn with the poetics of imagism he tended to appeal to the visual as a model for an affective “pattern” capable of curbing the unfocussed expression of emotion he associated with the backwash of Romanticism.3 It was here that the term “rhetoric” was constantly invoked as the enemy or the other of modernism. The imagist program, with its call for “direct treatment of the ‘thing’,” verbal economy, and rhythms determined by “the sequence of the musical phrase,” was underpinned by both the Kantian criticism of rhetoric as “the art of persuasion, i.e., of deceiving by a beautiful show (ars oratoria)”4 and by the assumption that rhetoric trafficked in some sort of merely verbal excess. Kant was not objecting to persuasion per se, of course, but to what he called a rhetorical “machinery of 1 “The Prose Tradition in Verse” (1914), in Literary Essays of Ezra Pound, ed. -

1 “Anarchival Modernism and the Documentary Poetics of Ezra

1 “Anarchival Modernism and the Documentary Poetics of Ezra Pound’s Late Cantos” Mitchell C. Brown, Department of English McGill University, Montreal April 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts. © Mitchell C. Brown 2014 2 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Preface 5 Appendix 6 Introduction 7-11 Chapter One: Modernism and the Archive 12-33 The “B.M. Era” – 1870-1930 Ezra Pound and Documentary Modernism The Cantos and the Problem of Documentary Poetics Chapter Two: The Pisan Cantos and Mnemonic Lyric 34-51 The Poetic Subject and Lyrical Control Mnemonics and the Subject Document Chapter Three: Section Rock-Drill: Realizing the Ideogrammic Method 52-74 Ideogrammic Transcription Structural Returns and Contractions Natural Law and Ideogrammic Reading Chapter Four: The Ideogram and the Archive 75-91 Archival Limits and the Ideogrammic Proposal Ideogrammic Limits and the Problem of Memory Conclusion 92-94 Works Cited 95-99 3 Abstract The purpose of this study is to examine the ways in which American modernist Ezra Pound’s “documentary poetics” serve a broader historical and cultural function as archival spaces. Stepping off from Eivind Røssaak’s identification of contemporary media culture as anarchival, this thesis aims to show how modernism’s pre-digital aesthetic experiments with documentary forms presaged this turn away from traditional forms of archival thinking. The first chapter surveys the intellectual legacies of archival epistemology from the Enlightenment through to the twentieth century, identifying the inter-war modernist movement as a definitive turning point towards new forms of figuring documentary history. -

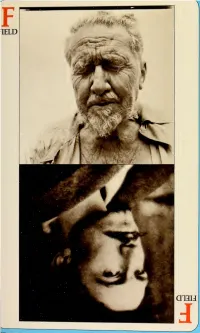

FIELD, Issue 33, Fall 1985

FIELD CONTEMPORARY POETRY AND POETICS NUMBER 3 3 FALL 1985 PUBLISHED BY OBERLIN COLLEGE OBERLIN, OHIO EOJTORS Stuart Friehert David Young ASSOCIATE Alberta Turner EDITORS David Walker BUSINESS Dolorus Nevels MANAGER EDITORIAL Lia Purpura ASSISTANT COVER Stephen j. Parkas Jr. FIELD gratefully acknowledges support from the Ohio Arts Council. Published twice yearly by Oberlin College. Subscriptions and manuscripts should be sent to FIELD, Rice Hall, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio 44074. Manuscripts will not be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. Subscriptions: $7.00 a year/$12.00 for two years/single issues $3.50 postpaid. Back issues 1, 4, 7, 15-31: $10.00 each. Issues 2-3, 5-6, 8-14 are out of print. Copyright ® 1985 by Oberlin College. CONTENTS 5 Ezra Pound: A Symposium Donald Hall 8 Pound's Sounds William Matthews 15 Young Ezra Stanley Plmnly 19 Pound's Garden James Laughlin 26 Rambling Around Pound's Propertius Norman Duhie 39 Into the Sere and Yellow Carol Muske 55 Alba LXXIX Charles Wright 63 Improvisations on Pound * * Sachiko Yoshihara 71 From the Afterworld Dennis Schm.itz 73 So High 75 Driving With One Light Miroslav Holuh 77 Crush Syndrome 78 Vanishing Lung Syndrome 80 Hemophilia Ralph Burns 82 Luck Charlie Smith 85 By Fire 86 Discovery Thomas Lux 87 Barracuda 88 Traveling Exhibit of Torture Instruments Garrett Kaoru Hongo 89 The Unreal Dwelling: My Years Volcano William Stafford 93 Surrounded by Mountains 94 Crowded Falls 95 Outside Wichita Susan Prospere 96 Saturnalia 99 House of Straw W1 Contributors EZRA POUND A FIELD SYMPOSIUM EZRA POUND: A SYMPOSIUM Even if this were not Ezra Pound's hundredth year, we would probably have succumbed to the urge to organize this sym- posium in his honor. -

Special Essay

Ó American Sociological Association 2011 DOI: 10.1177/0094306111419106 http://cs.sagepub.com SPECIAL ESSAY Modernism MARY DE RACHEWILTZ, Brunnenberg, Italy ‘‘miracleoffiveintelligentvisitors/such a gathering possible OUTSIDE a bughouse ?’’ Editor’s note: An invited essay inspired by wrote Ezra Pound to Olivia Rossetti Agresti Modernism in the Magazines: An from St. Elizabeths Hospital. In Rome, Via Introduction,byRobert Scholes and Ciro Menotti 36, the old lady did her best. Clifford Wulfman. New Haven, CT: She offered tea on Sunday afternoon. Her Yale University Press, 2010. 340pp. ‘‘gathering’’ consisted of three contempora- $40.00 cloth. ISBN: 9780300142044. ries: her sister Helen, usually accompanied by her daughter Imogen Dennis, Luigi Mary de Rachewiltz is the daughter of Villari, Cammillo Pellizzi and a young cou- Ezra Pound. ple in their twenties. ORA’s voice, lined with transparent irony when speaking of ‘‘isms,’’ used to quote her uncle, the ‘‘Pre- since in the appendix, Studies in Contempo- Rafaelite’’ Dante Gabriel Rossetti: ‘‘I am no rary Mentality, Pound is allowed to speak for Ite, I am a Poet.’’ Thus teaching the young himself. The book opens with three epigraphs, to ‘‘sort out the animals,’’ i.e., learn the two quotations from letters to James Joyce and names and the dates of the founders and of Wyndham Lewis and one from Make It New, participants in various movements, as well with the incisive statement : ‘‘You can’t as examine their motives and productions. know an era merely by knowing its best’’ Pound has been known as the founder of (p. 1). It might equally be said: by knowing Imagism and Vorticism, though he soon its worst, let alone when speaking of a poet went his own way. -

“Tortured Shadows: Representations of Lynching in Modernist U.S. Poetry” Milton Lamont Welch Raleigh, NC A.B. Philosophy, Va

“Tortured Shadows: Representations of Lynching in Modernist U.S. Poetry” Milton Lamont Welch Raleigh, NC A.B. philosophy, Vassar College, 1999 M.A. Liberal Arts, St. John’s College, Annapolis, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Language and Literature University of Virginia January, 2007 Abstract: In “Tortured Shadows: Representations of Lynching in the Modernist U.S. Poetry,” I examine the role of modernist lynching figures in U.S. poetry. These figures developed both in and apart from protest traditions of modernist poetry in the United States, and I emphasize both traditions as vital sites both for counter-articulations to the traumatic social impact of lynching and for resisting its ideological grounding. Without much political investment in the social question of lynchings, such poets as T.S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens and Ezra Pound represent lynching while invoking anxieties about their own identities as poets. Among traditions of protest, poets stir readers to political activism by encoding in the representation of lynching strategies of active individual and communal resistance. I term this strategy of protest and conversion didactic. Modernist protest poetry is often didactic, offering instruction in order to convert readers into social activism. Rather than appeals to social identity in protesting lynching, this protest poetry comes to depend on affective figures of lynch victims, figures, that is, of emotional identification. This study analyzes modernist lynching figures in non-protest poetry, but is chiefly a literary history of the evolving strategies of protest involving modernist lynching figures in poetry. -

Modernism's “Doors of Perception”: from Ezra Pound's Ideogrammic Method to Marshall Mcluhan's “Mosaic”

UDC 82.111(73) DOI 10.22455/2541-7894-2019-7-377-393 Panayiotes T. TRYPHONOPOULOS Demetres P. TRYPHONOPOULOS MODERNISM’S “DOORS OF PERCEPTION”: FROM EZRA POUND’S IDEOGRAMMIC METHOD TO MARSHALL MCLUHAN’S “MOSAIC” Abstract: Writing to Ezra Pound in May 1948, Marshall McLuhan told the poet that, “we [that is, Hugh Kenner and I] have long taken a serious interest [in] your work.” And so, McLuhan along with Kenner visited Pound at St Elizabeths in June 1948. The rest makes for interesting modernist literary and cultural studies history. This paper argues that McLuhan’s method of composition, which he called a “mosaic,” derives from his understanding of Pound’s poetics of the ideogrammic method. In The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (1962), McLuhan explains that the book “develops a mosaic or field approach to its problems. Such a mosaic image of numerous data and quotations in evidence offers the only prac- tical means of revealing the causal operations in history.” McLuhan learned much from the American poet, including to view literature/pedagogy as “training of per- ception”; and both developed texts that placed readers in media res, encouraging an heuristic approach to “reading” whereby readers are empowered to arrive at their own meaning or interpretation irrespective of the writers’ ideology and/or agenda. Using examples from The Cantos and The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects (1967), this essay also probes the relationships between mod- ernist aesthetics, technological prophesy and sociopolitical praxis. Keywords: Pound, McLuhan, modernism, ideogrammic method, mosaic, “the medium is the message.” © 2019 Panayiotes T. -

Remembering As a Source of Creation in the Poetry of Ezra Pound and H.D

Lawrence University Lux Lawrence University Honors Projects 5-31-2012 Remembering as a Source of Creation in the Poetry of Ezra Pound and H.D. and the Musical Representations of the Holocaust by Arnold Schoenberg and Steve Reich Ruth J. Jacobs Lawrence University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lux.lawrence.edu/luhp Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Musicology Commons © Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Recommended Citation Jacobs, Ruth J., "Remembering as a Source of Creation in the Poetry of Ezra Pound and H.D. and the Musical Representations of the Holocaust by Arnold Schoenberg and Steve Reich" (2012). Lawrence University Honors Projects. 23. https://lux.lawrence.edu/luhp/23 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Lux. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lawrence University Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Lux. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ruth Jacobs Remembering as a Source of Creation in the Poetry of Ezra Pound and H.D. and the Musical Representations of the Holocaust by Arnold Schoenberg and Steve Reich. Memory is a kind of accomplishment a sort of renewal even an initiation, since the spaces it opens are new places -William Carlos Williams 1 1 William Carlos Williams, Patterson (New York: New Directions Books, 1946), 78. To remember is to confront the force of forgetting, to acknowledge a past that is no longer complete, but fragmented by the passage of time. Perhaps that is why we cling to old photographs, handwritten letters, and other objects. -

Pound's Pictographing Technique in the Pisan Cantos

GORILLA LANGUAGE: POUND'S PICTOGRAPHING TECHNIQUE IN THE PISAN CANTOS BY YOON SIK JIM Bachelor of Arts Cheongju University Cheongju, South Korea 1978 Master of Human Relations University of Oklahoma Norman, Oklahoma 1982 Submit ted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 1991 GORILLA LANGUAGE: POUND'S PICTOGRAPHING TECHNIQUE IN THE PISAN CANTOS Thesis Approved: <:::::::: ~ ~sis Adviser ~ ~-~i Dean of the Graduate College ii PREFACE The highly original poetic techniques Ezra Pound em ploys in his Pisan cantos are a direct result of his serious concern and careful attempt to create a unique poetic medi um, a verbum perfectum, or a gorilla language that is hard, precise, and concrete. To this end, he creates an interac tion between the Chinese ideograms and the English text. Through his careful line breaks, Pound makes the English text visually rn i r ror the spatial contour of the ideograms. Such a "pictographing" technique points to two important facts: Pound's attempt to create an ideogram-like poetic medium and his attempt to freeze time via a temporal tempo rality in art, a task heretofore thought impossible. In fact, Modernists, such as Stein and Williams, have all tried to slow down tjme, having been also influenced by the aes thetics of the modern visual arts, Cubism in particular. Pound, a Picasso of modern poetry, broke the old tradition through a series of innovation involving, line breaks, fragmentation, and juxtaposition of Chinese and English text. Pound's "gorilla language" in the Pi san cantos truly marks a turning point in his poetic style.