Psalms, Poetry and Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ludere Causa Ludendi QUEEN's PARK FOOTBALL CLUB

QUEEN’S PARK FOOTBALL CLUB 1867 - 2017 150 Years in Scottish Football...... And Beyond Souvenir Brochure July 2017 Ludere Causa Ludendi President’s Foreword Welcome to our 150th Anniversary Brochure. At the meeting which took place on 9th July 1867, by the casting vote of the chairman and first President, Mungo Ritchie, the name of the club to be formed became “Queen’s Park” as opposed to “The Celts,” and Scottish Football was born. Our souvenir brochure can only cover part of our history, our role in developing the game both at home and abroad, our development of the three Hampden Parks, and some of our current achievements not only of our first team, especially the third Hampden Park is still evident as the but of our youth, community and women’s development site continues to evolve and modernise. Most importantly programmes, and our impressive JB McAlpine Pavilion at we continue our commitment to the promotion and Lesser Hampden. development of football in Scotland - and beyond. No. 3 Eglinton Terrace is now part of Victoria Road, but the This brochure is being published in 2017. I hope you enjoy best of our traditions remain part of us 150 years later. We reading it, and here’s to the next 150 years! remain the only amateur club playing in senior football in the UK; we are the oldest club in Scotland; and the vision Alan S. Hutchison of our forebears who developed the first, second and President The Formation of Queen’s Park FC, 9th July 1867 Queen’s Park FC, Scotland’s first association football club, ‘Glasgow, 9th July, 1867. -

Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten MacGregor, Martin (2009) Gaelic barbarity and Scottish identity in the later Middle Ages. In: Broun, Dauvit and MacGregor, Martin(eds.) Mìorun mòr nan Gall, 'The great ill-will of the Lowlander'? Lowland perceptions of the Highlands, medieval and modern. Centre for Scottish and Celtic Studies, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, pp. 7-48. ISBN 978085261820X Copyright © 2009 University of Glasgow A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/91508/ Deposited on: 24 February 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages MARTIN MACGREGOR One point of reasonably clear consensus among Scottish historians during the twentieth century was that a ‘Highland/Lowland divide’ came into being in the second half of the fourteenth century. The terminus post quem and lynchpin of their evidence was the following passage from the beginning of Book II chapter 9 in John of Fordun’s Chronica Gentis Scotorum, which they dated variously from the 1360s to the 1390s:1 The character of the Scots however varies according to the difference in language. For they have two languages, namely the Scottish language (lingua Scotica) and the Teutonic language (lingua Theutonica). -

Book of Condolences

Book of Condolences Ewan Constable RIP JIM xx Thanks for the best childhood memories and pu;ng Dundee United on the footballing map. Ronnie Paterson Thanks for the memories of my youth. Thoughts are with your family. R I P Thank you for all the memoires, you gave me so much happiness when I was growing up. You were someone I looked up to and admired Those days going along to Tanadice were fantasEc, the best were European nights Aaron Bernard under the floodlights and seeing such great European teams come here usually we seen them off. Then winning the league and cups, I know appreciate what an achievement it was and it was all down to you So thank you, you made a young laddie so happy may you be at peace now and free from that horrible condiEon Started following United around 8 years old (1979) so I grew up through Uniteds glory years never even realised Neil smith where the success came from I just thought it was the norm but it wasn’t unEl I got a bit older that i realised that you were the reason behind it all Thank you RIP MR DUNDEE UNITED � � � � � � � � Michael I was an honour to meet u Jim ur a legend and will always will be rest easy jim xxx� � � � � � � � First of all. My condolences to Mr. McLean's family. I was fortunate enough to see Dundee United win all major trophies And it was all down to your vision of how you wanted to play and the kind of players you wanted for Roger Keane Dundee United. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-10803-5 - Modernism and Homer: The Odysseys of H.D., James Joyce, Osip Mandelstam, and Ezra Pound Leah Culligan Flack Index More information Index “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste” Classics (1912), 3 and pedantry, 132, 193 Abyssinia crisis, 140–1 decline in the study of, 13, 133 Acmeism, 15, 59, 70 Coburn, Alvin Langdon, 157 Adams, John, 2, 128, 130–1, 142–3, 153 Crisis in the humanities, 19, 206 Aeneid. See Virgil Aeschylus, 165–6, 173 d’Este, Niccolo, 53 Akhmatova, Anna, 15, 59, 63, 78, 82, 88 Dante, 37, 50, 69, 93, 157 Anderson, Margaret, 100 Dickinson, Emily, 190 Apollinaire, Guillaume, 197 Divus, Andreas (Justinopolitanus), 14, 25, 36–43, Arnold, Matthew, 10, 136, 166 50, 154 Atwood, Margaret, 203 Dörpfeld, Wilhelm, 11 Austin, Norman, 177 Downes, Jeremy, 180 DuPlessis, Rachel Blau, 9, 162 Balfour, Arthur James, 140 Barnhisel, Gregory, 8, 128, 158–9 Ehrenburg, Ilya, 78 Barthes, Roland, 79–80 Eliot, T. S., 4, 6, 28, 95, 151, 159, 162, 165–6, 181 Bate, W. Jackson, 21 mythic method, 8 Beecroft, Alexander, 180 The Waste Land, 16, 42, 47, 165, 195, 199 Benjamin, Walter, 196 Ellison, Ralph Bérard, Victor, 15, 99, 103 Invisible Man, 201–2 Bethea, David, 13, 60 Ellmann, Richard, 96, 107, 114, 197 Bishop, Elizabeth, 160–1 Emerson, Ralph Waldo, 29, 190 Brodsky, Joseph, 200 Emmet, Robert, 108, 115 Brooke, Rupert, 1 epic, 164, 180, 186, See also Pound, Ezra and epic; Brown, Clarence, 93 Mandelstam, Osip and epic; and H.D. Brown, Richard, 95 and epic Budgen, Frank, 104 epic vs. -

Full Bibliography (PDF)

SOMHAIRLE MACGILL-EAIN BIBLIOGRAPHY POETICAL WORKS 1940 MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. 17 Poems for 6d. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. Seventeen Poems for Sixpence [second issue with corrections]. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. 1943 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir agus Dàin Eile. Glasgow: William MacLellan, 1943. 1971 MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. London: Victor Gollancz, 1971. MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. (Northern House Pamphlet Poets, 15). Newcastle upon Tyne: Northern House, 1971. 1977 MacLean, S. Reothairt is Contraigh: Taghadh de Dhàin 1932-72 /Spring tide and Neap tide: Selected Poems 1932-72. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1977. 1987 MacLean, S. Poems 1932-82. Philadelphia: Iona Foundation, 1987. 1989 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh / From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. Manchester: Carcanet, 1989. 1991 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/ From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. London: Vintage, 1991. 1999 MacLean, S. Eimhir. Stornoway: Acair, 1999. MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and in English translation. Manchester and Edinburgh: Carcanet/Birlinn, 1999. 2002 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir/Poems to Eimhir, ed. Christopher Whyte. Glasgow: Association of Scottish Literary Studies, 2002. MacLean, S. Hallaig, translated by Seamus Heaney. Sleat: Urras Shomhairle, 2002. PROSE WRITINGS 1 1945 MacLean, S. ‘Bliain Shearlais – 1745’, Comar (Nollaig 1945). 1947 MacLean, S. ‘Aspects of Gaelic Poetry’ in Scottish Art and Letters, No. 3 (1947), 37. 1953 MacLean, S. ‘Am misgear agus an cluaran: A Drunk Man looks at the Thistle, by Hugh MacDiarmid’ in Gairm 6 (Winter 1953), 148. -

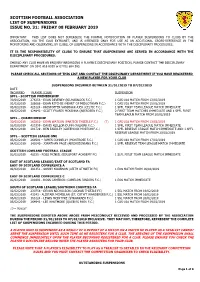

Scottish Football Association List of Suspensions Issue No

SCOTTISH FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION LIST OF SUSPENSIONS ISSUE NO. 31: FRIDAY 08 FEBRUARY 2019 IMPORTANT – THIS LIST DOES NOT SUPERSEDE THE FORMAL NOTIFICATION OF PLAYER SUSPENSIONS TO CLUBS BY THE ASSOCIATION, VIA THE CLUB EXTRANET, AND IS INTENDED ONLY FOR USE AS AN ADDITIONAL CROSS-REFERENCE IN THE MONITORING AND OBSERVING, BY CLUBS, OF SUSPENSIONS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. IT IS THE RESPONSIBILITY OF CLUBS TO ENSURE THAT SUSPENSIONS ARE SERVED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. SHOULD ANY CLUB HAVE AN ENQUIRY REGARDING A PLAYER’S DISCIPLINARY POSITION, PLEASE CONTACT THE DISCIPLINARY DEPARTMENT ON 0141 616 6018 or 07702 864 165. PLEASE CHECK ALL SECTIONS OF THIS LIST AND CONTACT THE DISIPLINARY DEPARTMENT IF YOU HAVE REGISTERED A NEW PLAYER FOR YOUR CLUB SUSPENSIONS INCURRED BETWEEN 31/01/2019 TO 07/02/2019 DATE INCURRED PLAYER (CLUB) SUSPENSION SPFL - SCOTTISH PREMIERSHIP 30/01/2019 276256 - EUAN DEVENEY (KILMARNOCK F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 01/02/2019 386086 - DEAN RITCHIE (HEART OF MIDLOTHIAN F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 15/02/2019 03/02/2019 423124 - KRISTOFFER VASSBAKK AJER (CELTIC F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 124842 - SCOTT FRASER MCKENNA (ABERDEEN F.C.) 2 FIRST TEAM MATCHES IMMEDIATE AND 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH FROM 20/02/2019 SPFL – CHAMPIONSHIP 30/01/2019 260210 - DEAN WATSON (PARTICK THISTLE F.C.) (T) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 02/02/2019 425359 - DAVIS KEILLOR-DUNN (FALKIRK F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 201729 - BEN -

Chap 2 Broun

222 Attitudes of Gall to Gaedhel in Scotland before John of Fordun DAUVIT BROUN It is generally held that the idea of Scotland’s division between Gaelic ‘Highlands’ and Scots or English ‘Lowlands’ can be traced no further back than the mid- to late fourteenth century. One example of the association of the Gaelic language with the highlands from this period is found in Scalacronica (‘Ladder Chronicle’), a chronicle in French by the Northumbrian knight, Sir Thomas Grey. Grey and his father had close associations with Scotland, and so he cannot be treated simply as representing an outsider’s point of view. 1 His Scottish material is likely to have been written sometime between October 1355 and October 1359.2 He described how the Picts had no wives and so acquired them from Ireland, ‘on condition that their offspring would speak Irish, which language remains to this day in the highlands among those who are called Scots’. 3 There is also an example from the ‘Highlands’ themselves. In January 1366 the papacy at Avignon issued a mandate to the bishop of Argyll granting Eoin Caimbeul a dispensation to marry his cousin, Mariota Chaimbeul. It was explained (in words which, it might be expected, 1See especially Alexander Grant, ‘The death of John Comyn: what was going on?’, SHR 86 (2007) 176–224, at 207–9. 2He began to work sometime in or after 1355 while he was a prisoner in Edinburgh Castle, and finished the text sometime after David II’s second marriage in April 1363 (the latest event noted in the work); but he had almost certainly finished this part of the chronicle before departing for France in 1359: see Sir Thomas Gray, Scalacronica, 1272–1363 , ed. -

PRELIMINARIES (A) Celtic FC Foundation, a Registered Scottish Charitable Incorporated Organisation with the Office of the Scotti

PRELIMINARIES (A) Celtic FC Foundation, a registered Scottish Charitable Incorporated Organisation with the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator (number SC024648) and having its place of business at Celtic Park, Glasgow, G40 3RE (“Celtic FC Foundation”). (B) The following terms and conditions apply to participants in Celtic FC Foundation’s The H.E.L.P Pilgrimage on Monday, 30 May 2016 (the “Event”). Please take time to read these carefully as you are bound by them, on acceptance by Celtic FC Foundation of your entry. (C) All monies will be managed by Celtic FC Foundation and the net proceeds of the monies raised –will be retained by Celtic FC Foundation for delivery of its charitable activities. (D) By registering for the Event, you are agreeing to the following conditions of entry and any instructions given to you by Celtic FC Foundation. 1. Event Details (a) This event features a 17 mile walk encompassing four historical sites (St Mary’s Church, Barrowfield, Jimmy Johnstone Memorial Statue in Viewpark and finally, Celtic Park) and honouring four legendary figures in Celtic FC’s history (Tommy Burns, Jock Stein, Jimmy Johnstone and Brother Walfrid) at each respective venue. (b) The Event will commence at St Mary’s Parish Church, 89 Abercromby Street, Glasgow G40 2DQ (the “Venue”). (c) The Event is scheduled to take place on Monday, 30 May 2016 (the “Event Date”). However, Celtic FC Foundation cannot predict the weather and forecasts can sometimes be unreliable. Therefore, there is no guarantee the Event will take place on that day and an alternative may need to be arranged. -

Download Northwords Now to an E-Reader

The FREE literary magazine of the North Northwords Now Issue 28, Autumn 2014 AND STILL THE DANCE GOES ON Referendum Poems by John Glenday, Aonghas Pàdraig Caimbeul, Sheenah Blackhall and others New stories and poems including Wayne Price, Ian Macpherson, Kenneth Steven and Irene Evans In the Reviews Section: Cynthia Rogerson gets hooked on farming EDITORIAL Contents week or so before the referendum I put out a call for September 19th poems via our Facebook page and by direct appeal to some 3 The Morning After: Poems for September 19th A of the many frequent contributors to the magazine. I was keen that poems had to be submitted on the day after the referendum. I 6 A Brisk Hike Up The Trossachs wanted a spontaneous heart-and-head-and-soul reaction, whatever the Short Story by Ian Macpherson result. You can read the poems for yourself on pages 3-5. It’s fair to say that the dominant note struck by the writers is one of regret – even, 7 Poems by Diana Hendry, Richie McCaffery in some cases hurt - whether that takes the form of dry humour or full-on lament. 8 Poems by Judith Taylor It is also fair to say – putting referendum politics to one side for a moment – that these are poems that exhibit, in their different ways, a 9 Radio Lives: Stories from Barra feeling for Scotland that springs from many different wells and takes Article by Janice Ross a variety of forms. Scots today are, after all, a diverse people. A host of narratives play their part in forming the character of the country. -

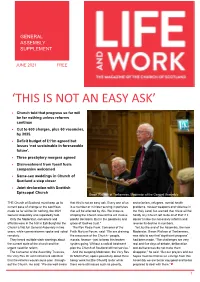

'This Is Not an Easy Ask'

GENERAL ASSEMBLY SUPPLEMENT JUNE 2021 FREE ‘THIS IS NOT AN EASY ASK’ • Church told that progress so far will be for nothing unless reforms continue • Cut to 600 charges, plus 60 vacancies, by 2025. • Deficit budget of £11m agreed but losses ‘not sustainable in foreseeable future’. • Three presbytery mergers agreed • Disinvestment from fossil fuels companies welcomed • Same-sex weddings in Church of Scotland a step closer • Joint declaration with Scottish Episcopal Church Baron Wallace of Tankerness, Moderator of the General Assembly THE Church of Scotland must keep up its that this is not an easy ask. Every one of us sectarianism, refugees, mental health current pace of change or the sacrifices is a member or minister serving in parishes problems, nuclear weapons and violence in made so far will be for nothing, the 2021 that will be affected by this. We know re- the Holy Land, but warned that ‘there will be General Assembly was repeatedly told. shaping the Church around this will involve hardly any Church left to do all of that’ if it Only the Moderator, conveners and painful decisions. But in the goodness and doesn’t make the necessary reforms and officials were in the hall in Edinburgh for the grace of God we trust.” reverse its decline in numbers. Church’s first full General Assembly in two The Rev Rosie Frew, Convener of the Yet, by the end of the Assembly, the new years, while commissioners spoke and voted Faith Nurture Forum, said: “We are draining Moderator, Baron Wallace of Tankerness, remotely. the resources of the Church - people, was able to say that ‘significant progress’ They heard multiple stark warnings about morale, finance - just to keep this broken had been made. -

A Poem Containing History": Pound As a Poet of Deep Time Newell Scott Orp Ter Brigham Young University

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive All Theses and Dissertations 2017-03-01 "A poem containing history": Pound as a Poet of Deep Time Newell Scott orP ter Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Porter, Newell Scott, ""A poem containing history": Pound as a Poet of Deep Time" (2017). All Theses and Dissertations. 6326. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6326 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “A poem containing history”: Pound as a Poet of Deep Time Newell Scott Porter A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Edward Cutler, Chair Jarica Watts John Talbot Department of English Brigham Young University Copyright © 2017 Newell Scott Porter All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT “A poem containing history”: Pound as a Poet of Deep Time Newell Scott Porter Department of English, BYU Master of Arts There has been an emergent trend in literary studies that challenges the tendency to categorize our approach to literature. This new investment in the idea of “world literature,” while exciting, is also both theoretically and pragmatically problematic. While theorists can usually articulate a defense of a wider approach to literature, they struggle to develop a tangible approach to such an ideal. -

The Church: Towards a Common Vision

ONE IN CHRIST CONTENTS VOLUME 49 (2015) NUMBER 2 ARTICLES The Church: Towards a Common Vision. A Faith and Order Perspective. Mary Tanner 171 Towards the Common Good. A Church and Society Perspective on The Church: Towards a Common Vision. William Storrar 182 Catholic Perspectives on The Church: Towards A Common Vision. Catherine E. Clifford 192 Questions of Unity, Diversity and Authority in The Church: Towards a Common Vision. Advances and Tools for Ecumenical Dialogue. Kristin Colberg 204 Catholic Appropriation and Critique of The Church: Towards a Common Vision. Brian P. Flanagan 219 Communion and Communication among the Churches in the Tradition of Alexandria. Mark Sheridan OSB 235 Squaring the Circle: Anglicans and the Recognition of Holy Orders. Will Adam 254 Ecumenism: Why the Slow Progress? Gideon Goosen 270 REPORTS The Fiftieth Anniversary of the Corrymeela Community. Pádraig Ó Tuama 285 The Hurley Legacy: a personal appreciation. Paddy Kearney 294 Saint Irenaeus Joint Orthodox-Catholic Working Group. Communiqué – Halki 2015 299 A Contribution from the Anglican-Roman Catholic Dialogue of Canada to the Anglican Church of Canada’s Commission on the Marriage Canon. 303 BOOK REVIEWS 317 170 ONE IN CHRIST VOL.49 NO.2 EDITORIAL Most of the articles in this issue are devoted to The Church: Towards a Common Vision (Faith and Order Paper 214, WCC 2013). We are pleased to publish contributions from the Catholic Theological Society of America (Clifford, Colberg, Flanagan), and papers originating in the December 2015 conference of the Joint Commission on Doctrine of the Church of Scotland and the Roman Catholic Church (Tanner, Storrar).