Female Drug Use in Pakistan Was Launched by UNODC in 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REFORM OR REPRESSION? Post-Coup Abuses in Pakistan

October 2000 Vol. 12, No. 6 (C) REFORM OR REPRESSION? Post-Coup Abuses in Pakistan I. SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................................2 II. RECOMMENDATIONS.......................................................................................................................................3 To the Government of Pakistan..............................................................................................................................3 To the International Community ............................................................................................................................5 III. BACKGROUND..................................................................................................................................................5 Musharraf‘s Stated Objectives ...............................................................................................................................6 IV. CONSOLIDATION OF MILITARY RULE .......................................................................................................8 Curbs on Judicial Independence.............................................................................................................................8 The Army‘s Role in Governance..........................................................................................................................10 Denial of Freedoms of Assembly and Association ..............................................................................................11 -

MIRPUR PAPERS, Volume 22, Issue 23, November 2016

ISSN: 1023-6325 MIRPUR PAPERS, Volume 22, Issue 23, November 2016 MIRPUR PAPERS Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka-1216 Bangladesh MIRPUR PAPERS Chief Patron Major General Md Saiful Abedin, BSP, ndc, psc Editorial Board Editor : Group Captain Md Asadul Karim, psc, GD(P) Associate Editors : Wing Commander M Neyamul Kabir, psc, GD(N) (Now Group Captain) : Commander Mahmudul Haque Majumder, (L), psc, BN : Lieutenant Colonel Sohel Hasan, SGP, psc Assistant Editor : Major Gazi Shamsher Ali, AEC Correspondence: The Editor Mirpur Papers Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka – 1216, Bangladesh Telephone: 88-02-8031111 Fax: 88-02-9011450 E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2006 DSCSC ISSN 1023 – 6325 Published by: Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka – 1216, Bangladesh Printed by: Army Printing Press 168 Zia Colony Dhaka Cantonment, Dhaka-1206, Bangladesh i Message from the Chief Patron I feel extremely honoured to see the publication of ‘Mirpur Papers’ of Issue Number 23, Volume-I of Defence Services Command & Staff College, Mirpur. ‘Mirpur Papers’ bears the testimony of the intellectual outfit of the student officers of Armed Forces of different countries around the globe who all undergo the staff course in this prestigious institution. Besides the student officers, faculty members also share their knowledge and experience on national and international military activities through their writings in ‘Mirpur Papers’. DSCSC, Mirpur is the premium military institution which is designed to develop the professional knowledge and understanding of selected officers of the Armed Forces in order to prepare them for the assumption of increasing responsibility both on staff and command appointment. -

Deh Safooran, Tappo Malir, Karachi

FEDERAL EMPLOYEES AIRPORT RESENDCIA KARACHI Project Is Located On Jinnah Avenue, Opposite Malir Cantonment And Adjacent To Karachi Airport. A Project of FGEHA With Smart Living Concept Smart Planning Concept 3, 4 & 5 Rooms Apartments JINNAH A VE PROPOSED ACACIA GOLF CLUB SITE FOR FGEHA TANK CHOWK VE VE TERMINAL A TIONAL JINNAH 14.20 ACRES JINNAH AVENUE ADJOINING KARACHI JINNAH INTERNA AIRPORT NEAR ACACIA GOLF CLUB 3, 4 & 5 Rooms Apartments State of the art facilities & amenities AIRPORT RD Introduction of FGEHA The Federal Government Employees Housing Authority was established through an act of parliament in January 2020. Main objective of FGEHA is to initiate, launch, sponsor and implement housing schemes for serving/retired Federal Government Employees on ownership basis in all major cities of Pakistan to eradicate shelterlessness. Before introduction of FGEHA Act 2020, it was known as Federal Government Employees Housing Foundation (FGEHF) under Ministry of Housing & Works, since 1989, as a guarantee limited company with Securities & Exchange Commission of Pakistan under section 42 of Companies Ordinance 1984. ACHIEVEMENTS FGE Housing Authority allotted number of units to its members in Islamabad,Peshawar & Karachi – 22483 number of units from 1989 to 2013 • 19421 Plots • 1595 Houses • 1467 Apartments – 32007 number of units from 2014 to 2019 planned/allotted to its members registered in Membership Drive Phase-I & Phase-II • 28923 Plots • 3084 Apartments Karachi City of Lights remains Pakistan's largest urban economy despite the economic stagnation caused by sociopolitical unrest during the late 1980s and 1990s. The city forms the centre of an economic corridor stretching from Karachi to nearby Hyderabad and Thatta. -

Download File

Cover and section photo credits Cover Photo: “Untitled” by Nurus Salam is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 (Shangu River, Bangladesh). https://www.flickr.com/photos/nurus_salam_aupi/5636388590 Country Overview Section Photo: “village boy rowing a boat” by Nasir Khan is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nasir-khan/7905217802 Disaster Overview Section Photo: Bangladesh firefighters train on collaborative search and rescue operations with the Bangladesh Armed Forces Division at the 2013 Pacific Resilience Disaster Response Exercise & Exchange (DREE) in Dhaka, Bangladesh. https://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonmildep/11856561605 Organizational Structure for Disaster Management Section Photo: “IMG_1313” Oregon National Guard. State Partnership Program. Photo by CW3 Devin Wickenhagen is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonmildep/14573679193 Infrastructure Section Photo: “River scene in Bangladesh, 2008 Photo: AusAID” Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/dfataustralianaid/10717349593/ Health Section Photo: “Arsenic safe village-woman at handpump” by REACH: Improving water security for the poor is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/reachwater/18269723728 Women, Peace, and Security Section Photo: “Taroni’s wife, Baby Shikari” USAID Bangladesh photo by Morgana Wingard. https://www.flickr.com/photos/usaid_bangladesh/27833327015/ Conclusion Section Photo: “A fisherman and the crow” by Adnan Islam is licensed under CC BY 2.0. Dhaka, Bangladesh. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adnanbangladesh/543688968 Appendices Section Photo: “Water Works Road” in Dhaka, Bangladesh by David Stanley is licensed under CC BY 2.0. -

Identification of Mosquito Species in Dhaka Cantonment

J. Asiat. Soc. Bangladesh. Sci. 40(2): 243-248, December 2014 IDENTIFICATION OF MOSQUITO SPECIES IN DHAKA CANTONMENT MD RAB1UL HOSSAIN1, MD. SHAHIDULLAH, NOZHAT NASREEN BANU' AND MD. MEHD1 HASAN JEWEL Combined Military Hospital (CMH), Dhaka, Bangladesh 'Armed Forces Medical College. Dhaka. Bangladesh Abstract The present study was carried out from 1st August 2011 to 31 January 2012 to identify mescu::; species inhabiting in and around the Dhaka Cantonment. In all 5632 samples size -.ere collected from 88 different spots. Important three genera such ns Anopheles, Cu.tx sac Aedes were found and distribution was as Culex 5581 (99.09%), Aedes 30 i j 5c':* anc Anopheles 21 (0.37%). Among the Culex species C. quinquefasciatus dominated and having 69.37% of Culex family. Other identified species were C. fuscocephala \ 14 89%), C. tritaeniorhynchus (09.07%) and C. vishnui (06.67%). The sex distnbunon of the sampled mosquitoes revealed that female dominated and male femile ratio was 34:66. There was predominance of C. quinquefasciatus in all collect: DO points. Anopheles was identified 21 (12 female) in number of which An phiiiptnensis *is 17 and An. aconitus only 04 and they were collected from four spots ofZia cc and COD areas. Ae. aegypti was identified 30 (22 female) in number of which -is aegypti were 23 and the rest 07 were Ae. albopictus and they were collected from se-er. .-pots of COD, Senapolli, Moinul Road and DOHS Mohakhali but its density .ery insignificant and below the critical level of disease transmission. Key words Mosquito, Anopheles, Culex, Aedes, Dhaka Cantonment Introduction Correct identification of vector mosquitoes is essential for the effective control and prevention of some of the most dangerous tropical diseases: Malaria, Dengue, Japanese encephalitis, and Filariasis. -

23Rd January, 2020 at 02:00 P.M

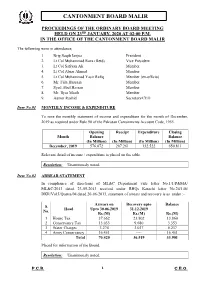

CANTONMENT BOARD MALIR PROCEEDINGS OF THE ORDINARY BOARD MEETING HELD ON 23RD JANUARY, 2020 AT 02:00 P.M. IN THE OFFICE OF THE CANTONMENT BOARD MALIR The following were in attendance; 1 Brig Saqib Janjua President 2. Lt Col Muhammad Raza (Retd) Vice President 3. Lt Col Safiyan Ali Member 4. Lt Col Abrar Ahmed Member 5. Lt Col Muhammad Yasir Rafiq Member (ex-officio) 6. Mr. Fida Hussain Member 7. Syed Abul Hassan Member 8. Mr. Ilyas Masih Member 9. Aamer Rashid Secretary/CEO Item No.01 MONTHLY INCOME & EXPENDITURE To note the monthly statement of income and expenditure for the month of December, 2019 as required under Rule 90 of the Pakistan Cantonments Account Code, 1955. Opening Receipt Expenditure Closing Month Balance Balance (In Million) (In Million) (In Million) (In Million) December, 2019 576.072 207.261 132.522 650.811 Relevant detail of income / expenditure is placed on the table. Resolution: Unanimously noted. Item No.02 ARREAR STATEMENT In compliance of directions of ML&C Department vide letter No.1/1/P&MA/ ML&C/2013 dated 23-05-2013 received under RHQs Karachi letter No.24/146/ DKR/Vol:I/Quetta/04 dated 20-06-2013, statement of arrears and recovery is as under :- Arrears on Recovery upto Balance S. Head Upto 30.06.2019 31.12.2019 No. Rs.(M) Rs.(M) Rs.(M) 1 House Tax 37.662 23.802 13.860 2 Conservancy Tax 13.033 9.680 3.353 3 Water Charges 3.274 3.037 0.237 4 Army Conservancy 16.451 ---- 16.451 Total 70.420 36.519 33.901 Placed for information of the Board. -

Development Strategy for the Hill Districts of Uttarakhand

Working Paper No. 217 Development Strategy for the Hill Districts of Uttarakhand Surabhi Mittal Gaurav Tripathi Deepti Sethi July 2008 INDIAN COUNCIL FOR RESEARCH ON 1INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC RELATIONS Table of Contents Foreword.........................................................................................................................i Abstract..........................................................................................................................ii Acknowledgments.........................................................................................................iii 1. Profile of Uttarakhand...............................................................................................1 1.1 Background.........................................................................................................1 1.2 Economic Profile of Uttarakhand .......................................................................2 1.3 Literature Review................................................................................................4 1.4 Government Initiatives........................................................................................6 1.5 Vision, Objectives and Plan of the study............................................................8 2. Agriculture and Agriculture-Based Systems ............................................................8 2.1 Agriculture Profile of Uttarakhand .....................................................................8 2.2 District Profile...................................................................................................12 -

TRAFFIC STUDY REPORT September 2019

MALIR EXPRESSWAY PROJECT TRAFFIC STUDY REPORT September 2019 Malir Expressway ---- MALIR EXPRESSWAY PROJECT TRAFFIC STUDY REPORT Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................. 3 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 Project Location & Background .......................................................................................... 8 1.2 Project Objectives ................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Objectives and Scope of Traffic Study ............................................................................ 10 1.4 References & Sources of Data ........................................................................................... 10 1.5 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. 11 2 ALIGNMENT AND COMPETITIVE ROUTES STUDY .............................................................. 12 2.1 Reconnaissance Study ........................................................................................................ 12 2.2 Start Point ................................................................................................................................. 13 2.3 Interchanges En-route ........................................................................................................ -

1. Persons Interviewed

Karachi Transportation Improvement Project Final Report APPENDIX-1 MEETINGS 1. Persons Interviewed During the Phase 1 study period, which is Karachi Transport Master Plan-2030, JICA Study Team (JST) has been visited different organizations and Departments to collect data and also meet the officials. The list of these officials and their department/organization are given below 1.1 CDGK Administrator/ DCO, City District Government Karachi 1.1.1 KMTC Director General, Karachi Mass Transit Cell, CDGK Director, (Planning & Coordination) Karachi Mass Transit Cell, CDGK. Director (T), KMTC, CDGK 1.1.2 Master Plan Executive District Officer, Master Plan Group of Offices, CDGK District Officer, Master Plan Group of Offices, CDGK 1.1.3 Transport & Communication Executive District Officer, Transport Department , CDGK District Officer (Parking & Terminal Management), Transport & Communication Department (TCD), CDGK District Officer, Policy, Planning & Design, Transport & Communication Dept. CDGK 1.1.4 Education Department Executive District Officer, Education(School) , CDGK 1.1.5 Works & Service Department Executive District Officer, W&S , CDGK 1.2 DRTA Superintendant, District Regional Authority, CDGK 1.3 Town Administration Administrator, Keamari Town Administrator, Baldia Town Administrator, Bin Qasim Town Administrator, Gulberg Town Administrator, Gadap Town Administrator, Gulshan Town Administrator, Jamshed Town Administrator, Korangi Town Administrator, Landhi Town Administrator, Liaquatabad Town Appendix 1 - 1 Karachi -

A Case of Study for Nuclear Power Plant Grade Water

1096 International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 10, Issue 4, April-2019 ISSN 2229-5518 An Investigation of the Padma River Water Quality Parameters near Rooppur Nuclear Power Plant: A case of study for Nuclear Power Plant grade water Md. Nur Salam, Md.Farhan Hasan, Md. Akhlak Bin Aziz Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering, Military Institute of Science and Technology, Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka,Bangladesh. Abstract— Water samples collected from five different points near under construction Rooppur Nuclear Power Plant were tested in this work to assess the availability of nuclear grade water. The average value of pH was found to be 8.02, mean value of Electrical Conductivity (EC) was found 430 µS/cm, Total Dissolve Solid (TDS) 215 ppm, Salinity 0.8, total Alkalinity 79.6 ppm, total hardness 149 ppm and Chloride Content was found 16.87ppm. The Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD), Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) and Dissolved Oxygen (DO) of water were founded to be 0.15 ppm, 31 ppm and 8.85 ppm respectively. Among the heavy metals the amount of Cr, Pb, As, Mn, Fe, Mn, Cd, Co, Ni were found to be 0.0041 ppm, 0.00602 ppm, 0.0088 ppm, 0.02 ppm, 0 ppm, 0.00099ppm, 0 ppm and 0.00182 ppm respectively by using atomic absorption spectrophotometer. The pH meter (HANNA Instrument HT 2002-0, S/N CO316002) was used to determine the pH. Total dissolved solids (TDS) and EC were determined by digital TDS meter and EC meter (HANNA -2003-02, S/N: CO1271A1) and to determine the chemical properties of the samples water various tests were done. -

Dhaka Environmentally Sustainable Water Supply Project – Primary Distribution Pipelines (Package 3.1)

Land Acquisition and Involuntary Resettlement Due Diligence Report Document Stage: Updated Draft for Consultation Project Number: 42173-013 November 2019 BAN: Dhaka Environmentally Sustainable Water Supply Project – Primary Distribution Pipelines (Package 3.1) Prepared by the Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority, Government of Bangladesh, for the Asian Development Bank. This updated land acquisition and involuntary resettlement due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Land Acquisition and Involuntary Resettlement Due Diligence Report Document Stage: Updated Draft for Consultation Project Loan Number: 3051 November 2019 Project Loan BAN: Dhaka Environmentally Sustainable Water Supply Project Primary Distribution Pipelines (Package 3.1) Prepared by the Dhaka WASA, Government of Bangladesh, for the Asian Development Bank. This is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. 2 CURRENCY -

In the Supreme Court of Pakistan

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (Original Jurisdiction) PRESENT: MR. JUSTICE IFTIKHAR MUHAMMAD CHAUDHRY, C.J. MR. JUSTICE JAWWAD S. KHAWAJA MR. JUSTICE GHULAM RABBANI Suo Motu Case No.10/2009 (Complaint regarding establishment of Makro-Habib Store on playground) For the applicant: In person. For Makro-Habib: Mr. Khalid Anwar, Sr. ASC (on 7.7.09, 24.8.09, 31.8.09, 2.9.09, 3.9.09) For A.W.T.: Mr. Wasim Sajjad, Sr. ASC Mr. Fayyaz Ahmad Rana, ASC Ch. Akhtar Ali, AOR For M/o Defence: Sardar M. Latif Khan Khosa, Attorney General for Pakistan (on 31.8.09, 2.9.09, 1.10.09 &, 2.10.09) Mr. Shah Khawar, DAG Raja Abdul Ghafoor, AOR For Citizens: Dr. Muhammad Raza Gardezi For KBCA: Mr. Arshad Ali Chaudhry, AOR/ASC For Mehfooz-un-Nabi: Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, ASC (on 7.7.09, 24.8.09, 31.8.09, 1.9.09, 2.9.09, 3.9.09) Mr. M. S. Khattak, AOR Date of hearing 20.10.2009 JUDGMENT JAWWAD S. KHAWAJA, J:- This case was initiated by the Court under Article 184 (3) of the Constitution, on the basis of a column written by Mr. Ardeshir Cowasjee, appearing in the daily “Dawn” dated 14.6.2009 titled “A plea to the Lord Chief Justice.” The ‘plea’ in the column related to land which was earlier used as a playground, but has since been built up and is presently occupied by a commercial structure. Mr. Cowasjee is a senior columnist and is known for espousing causes in furtherance of the public interest.