383. Subdural Block and the Anaesthetist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Do Bridging Veins Rupture Into the Virtual Subdural Space?

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.47.2.121 on 1 February 1984. Downloaded from Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1984;47:121-127 Why do bridging veins rupture into the virtual subdural space? T YAMASHIMA, RL FRIEDE From the Department ofNeuropathology, University of Gottingen, Gottingen, Federal Republic of Germany SUMMARY Electron microscopic data on human bridging veins show thin walls of variable thick- ness, circumferential arrangement of collagen fibres and a lack of outer reinforcement by arach- noid trabecules, all contributory to the subdural portion of the vein being more fragile than its subarachnoid portion. These features explain the laceration of veins and the subdural location of resultant haematomas. Most subdural haematomas due to venous bleeding walls are delicate, lacking muscle fibres, with only a have been attributed to lacerations in bridging veins. thin fibrous wall and a thin elastic lamina adjacent to These veins form short trunks passing directly from the endothelial layer. The conclusions of these two the brain to the dura mater, almost at right angles to authors, have gained wide acceptance, although guest. Protected by copyright. both. Between these two points, bridging veins take there was little evidence concerning the fragility of a straight course with no tortuosity to allow for the the vein walls. possible displacement of brain.' Trotter2 speculated The purpose of the present communication is to that subdural haematomas are invariably due to provide electron microscopic data on tissue fixed in trauma tearing large veins, an interpretation situ, which might throw some light on to the lacera- elaborated by Krauland.3 According to Leary,4 the tion mechanism of bridging veins and its relationship common sources of subdural haematomas are rup- to the development of subdural haematoma. -

Why Woodpecker Can Resist the Impact

Why woodpecker can resist the impact A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Zhe Zhang Master of Civil Engineering, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia School of Engineering College of Science, Engineering and Health RMIT University November 2019 II Declaration I certify that except where due acknowledgement has been made, the work is that of the author alone; the work has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award; the content of the thesis is the result of work which has been carried out since the official commencement date of the approved research program; any editorial work, paid or unpaid, carried out by a third party is acknowledged; and ethics procedures and guidelines have been followed. Zhe Zhang 30 November 2019 III Acknowledgments The research in this thesis could not have been completed without significant support from many individuals and organisations. I would like to take this opportunity to express my deep gratitude to all of them. Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my senior supervisor, Dr. Shiwei Zhou, for his wisdom in choosing this fascinating research topic for me and his constant encouragement and guidance. After the guidance of my Master graduation project, Dr. Zhou accepted me as one of the Ph.D. students and offered financial support for my first-year study at RMIT University. He has always been patient in providing guidance and offering supportive suggestions to me during my PhD candidature period. It is not an exaggeration to say that he has changed my life and his good characteristics have had a significant and positive impact on me which would be beneficial for the rest of my life. -

Subarachnoid Trabeculae: a Comprehensive Review of Their Embryology, Histology, Morphology, and Surgical Significance Martin M

Literature Review Subarachnoid Trabeculae: A Comprehensive Review of Their Embryology, Histology, Morphology, and Surgical Significance Martin M. Mortazavi1,2, Syed A. Quadri1,2, Muhammad A. Khan1,2, Aaron Gustin3, Sajid S. Suriya1,2, Tania Hassanzadeh4, Kian M. Fahimdanesh5, Farzad H. Adl1,2, Salman A. Fard1,2, M. Asif Taqi1,2, Ian Armstrong1,2, Bryn A. Martin1,6, R. Shane Tubbs1,7 Key words - INTRODUCTION: Brain is suspended in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-filled sub- - Arachnoid matter arachnoid space by subarachnoid trabeculae (SAT), which are collagen- - Liliequist membrane - Microsurgical procedures reinforced columns stretching between the arachnoid and pia maters. Much - Subarachnoid trabeculae neuroanatomic research has been focused on the subarachnoid cisterns and - Subarachnoid trabecular membrane arachnoid matter but reported data on the SAT are limited. This study provides a - Trabecular cisterns comprehensive review of subarachnoid trabeculae, including their embryology, Abbreviations and Acronyms histology, morphologic variations, and surgical significance. CSDH: Chronic subdural hematoma - CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid METHODS: A literature search was conducted with no date restrictions in DBC: Dural border cell PubMed, Medline, EMBASE, Wiley Online Library, Cochrane, and Research Gate. DL: Diencephalic leaf Terms for the search included but were not limited to subarachnoid trabeculae, GAG: Glycosaminoglycan subarachnoid trabecular membrane, arachnoid mater, subarachnoid trabeculae LM: Liliequist membrane ML: Mesencephalic leaf embryology, subarachnoid trabeculae histology, and morphology. Articles with a PAC: Pia-arachnoid complex high likelihood of bias, any study published in nonpopular journals (not indexed PPAS: Potential pia-arachnoid space in PubMed or MEDLINE), and studies with conflicting data were excluded. SAH: Subarachnoid hemorrhage SAS: Subarachnoid space - RESULTS: A total of 1113 articles were retrieved. -

Spinal Meninges Neuroscience Fundamentals > Regional Neuroscience > Regional Neuroscience

Spinal Meninges Neuroscience Fundamentals > Regional Neuroscience > Regional Neuroscience SPINAL MENINGES GENERAL ANATOMY Meningeal Layers From outside to inside • Dura mater • Arachnoid mater • Pia mater Meningeal spaces From outside to inside • Epidural (above the dura) - See: epidural hematoma and spinal cord compression from epidural abscess • Subdural (below the dura) - See: subdural hematoma • Subarachnoid (below the arachnoid mater) - See: subarachnoid hemorrhage Spinal canal Key Anatomy • Vertebral body (anteriorly) • Vertebral arch (posteriorly). • Vertebral foramen within the vertebral arch. MENINGEAL LAYERS 1 / 4 • Dura mater forms a thick ring within the spinal canal. • The dural root sheath (aka dural root sleeve) is the dural investment that follows nerve roots into the intervertebral foramen. • The arachnoid mater runs underneath the dura (we lose sight of it under the dural root sheath). • The pia mater directly adheres to the spinal cord and nerve roots, and so it takes the shape of those structures. MENINGEAL SPACES • The epidural space forms external to the dura mater, internal to the vertebral foramen. • The subdural space lies between the dura and arachnoid mater layers. • The subarachnoid space lies between the arachnoid and pia mater layers. CRANIAL VS SPINAL MENINGES  Cranial Meninges • Epidural is a potential space, so it's not a typical disease site unless in the setting of high pressure middle meningeal artery rupture or from traumatic defect. • Subdural is a potential space but bridging veins (those that pass from the subarachnoid space into the dural venous sinuses) can tear, so it is a common site of hematoma. • Subarachnoid space is an actual space and is a site of hemorrhage and infection, for example. -

Intracranial Hemorrhage

Intracranial Hemorrhage MARK MOSS, M.D. INTERVENTIONAL NEURORADIOLOGY WASHINGTON REGIONAL MEDICAL CENTER Definitions Stroke Clinical syndrome of rapid onset deficits of brain function lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death Transient Ischemic attack (TIA) Clinical syndrome of rapid onset deficits of brain function which resolves within 24 hours Epidemiology Stroke is the leading cause of adult disabilities 2nd leading cause of death worldwide 3rd leading cause of death in the U.S. 800,000 strokes per year resulting in 150,000 deaths Deaths are projected to increase exponentially in the next 30 years owing to the aging population The annual cost of stroke in the U.S. is estimated at $69 billion Stroke can be divided into hemorrhagic and ischemic origins 13% hemorrhagic 87% ischemic Intracranial Hemorrhage Collective term encompassing many different conditions characterized by the extravascular accumulation of blood within different intracranial spaces. OBJECTIVES: Define types of ICH Discuss best imaging modalities Subarachnoid hemorrhage / Aneurysms Roles of endovascular surgery Intracranial hemorrhage Outside the brain (Extra-axial) hemorrhage Subdural hematoma (SDH) Epidural hematoma (EDH) Subarachnoid hematoma (SAH) Intraventricular (IVH) Inside the brain (Intra-axial) hemorrhage Intraparenchymal hematoma (basal ganglia, lobar, pontine etc.) Your heads compartments Scalp Subgaleal Space Bone (calvarium) Dura Mater thick tough membrane Arachnoid flimsy transparent membrane Pia Mater tightly hugs the -

Meninges,Cerebrospinal Fluid, and the Spinal Cord

Homework PreLab 3 HW 3-4: Spinal Nerve Plexus Organization The Nervous System SPINAL CORD The Spinal Cord Continuation of CNS inferior to foramen magnum Simpler Conducts impulses to and from brain Two way conduction pathway Reflex actions The Spinal Cord Passes through vertebral canal Foramen magnum L2 Conus medullaris Filum terminale Cauda equina Cervical Cervical spinal nerves enlargement Dura and arachnoid Thoracic mater spinal nerves Lumbar enlargement Conus medullaris Lumbar Cauda spinal nerves equina Filum (a) The spinal cord and its nerve terminale Sacral roots, with the bony vertebral spinal nerves arches removed. The dura mater and arachnoid mater are cut open and reflected laterally. The Spinal Cord Spinal nerves 31 pairs Cervical and lumbar enlargements Nerves serving the upper & lower limbs emerge here Cervical Cervical spinal nerves enlargement Dura and arachnoid Thoracic mater spinal nerves Lumbar enlargement Conus medullaris Lumbar Cauda spinal nerves equina Filum (a) The spinal cord and its nerve terminale Sacral roots, with the bony vertebral spinal nerves arches removed. The dura mater and arachnoid mater are cut open and reflected laterally. Figure 12.29a The Spinal Cord Protection Bone Meninges CSF Spinal tap-inferior to L2 vertebra T12 Ligamentum flavum L5 Lumbar puncture needle entering subarachnoid space L4 Supra- spinous ligament L5 Filum terminale S1 Inter- Cauda equina vertebral Arachnoid Dura in subarachnoid disc matter mater space Figure 12.30 The Spinal Cord Cross section Central gray -

The Anatomy of the Murine Cortical Meninges Revisited for Intravital Imaging, Immunology, and Clearance of Waste from the Brain

Progress in Neurobiology Accepted for publication 8 May 2017. Review article Where are we? The anatomy of the murine cortical meninges revisited for intravital imaging, immunology, and clearance of waste from the brain. Jonathan A. Colesa,*, Elmarie Myburghb, James M. Brewera, Paul G. McMenaminc aCentre for Immunobiology, Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, Sir Graeme Davis Building, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8TA, United Kingdom. bCentre for Immunology and Infection Department of Biology, University of York, Wentworth Way, Heslington, York YO10 5DD, United Kingdom. cDepartment of Anatomy & Developmental Biology, School of Biomedical and Psychological Sciences and Monash Biomedical Discovery Institute, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, 10 Chancellor’s Walk, Clayton, Victoria, 3800, Australia. *Corresponding author at: [email protected]. ABSTRACT Rapid progress is being made in understanding the roles of the cerebral meninges in the maintenance of normal brain function, in immune surveillance, and as a site of disease. Most basic research on the meninges and the neural brain is now done on mice, major attractions being the availability of reporter mice with fluorescent cells, and of a huge range of antibodies useful for immunocytochemistry and the characterization of isolated cells. In addition, two-photon microscopy through the unperforated calvaria allows intravital imaging of the undisturbed meninges with sub-micron resolution. The anatomy of the dorsal meninges of the mouse (and, indeed, of all mammals) differs considerably from that shown in many published diagrams: over cortical convexities, the outer layer, the dura, is usually thicker than the inner layer, the leptomeninx, and both layers are richly vascularized and innervated, and communicate with the lymphatic system. -

Wk07 Sechand1015.Pdf

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu 9.01 Introduction to Neuroscience Fall 2007 For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms. 9.01 Recitation Section 1 (Mondays) Image removed due to copyright restrictions. medial v. lateral lateral – structures farther from the midline medial – structures closer to the midline i.e. the eyes are more medial than the ears ipsilateral v. contralateral contralateral – two structures on different sides ipsilateral – two structures on the same side i.e. the right ear is ipsilateral to the right eye Central Nervous System: • cerebrum (cerebral hemispheres divided by sagittal fissure; right hemisphere controls left side of body, vice versa) • cerebellum (as many neurons as the cerebrum; movement control center; extensive connections with cerebrum and spinal cord; left side of cerebellum controls left side of body, right controls right) • brain stem (relays information from spinal cord to cerebrum and cerebellum; regulates vital functions; most primitive part of brain, most vital to life) • spinal cord (encased in vertebrate column; communicates with body via spinal nerves, which attach to cord via dorsal root or ventral root) o dorsal root (sensory information) o ventral root (motor information) Peripheral Nervous System • somatic PNS (all spinal nerves that innervate skin, joints, muscles under voluntary control) • visceral PNS (aka autonomic nervous system; neurons that innervate internal organs, blood vessles, glands) afferent v. efferent afferent means -

It's a Stitch-Up: the Function of Subarachnoid Trabeculae

rauma & f T T o re l a t a m n r e u n o t J Journal of Trauma & Treatment Talbert, J Trauma Treat 2016, 5:3 ISSN: 2167-1222 DOI: 10.4172/2167-1222.1000318 Research Article Open Access It's a Stitch-Up: The Function of Subarachnoid Trabeculae David Godwin Talbert* Institute of Reproductive and Developmental Biology, Imperial College School of Medicine, Du Cane Road, London W12 ONN, UK *Corresponding author: David Godwin Talbert, Institute of Reproductive and Developmental Biology, Imperial College School of Medicine, Du Cane Road, London W12 ONN, UK, Tel: 02089698151; E-mail: [email protected] Rec date: Apr 13, 2016; Acc date: Jul 13, 2016; Pub date: Jul 15, 2016 Copyright: © 2016 Talbert DG. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract The Shaken Baby Hypothesis assumes the brain can slide in the skull, but trabeculae (thin strips of collagen reinforced tissue that link across the subarachnoid space) appear to prevent this. They are so thin that they are undetectable by ultrasound or MRI imaging systems. Pediatricians in the 1970s were unaware of their existence. The Shaken Baby Syndrome hypothesis ignores them. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether omitting the trabecular structures from the SBS hypothesis would have made any difference to the legal validity of cases based on it. When the Shaken Baby Syndrome concept was created in the 1970s it was believed that there was a layer of fluid between the Dura and Arachnoid Maters (a “Subdural Space”) which allowed the brain cortex to slide. -

Meninges Dr Nawal Alshannan MENINGES Latin Ward Means Membrane Meninx • Are Membranes Covering the Brain and Spinal Cord • Consist of Three Membranes: • 1

Meninges Dr nawal Alshannan MENINGES latin ward means membrane meninx • are membranes covering the brain and spinal cord • Consist of three membranes: • 1. The dura mater, • strong- tough mother • 2.The arachnoid mater spidery = hold blood vessels • 3.The pia mater • delicate membrane Dura mater Outermost layer Thick dense inelastic membrane It surrounds and supports the dural sinuses Dura mater has two layers = Bilaminar • 1. The superficial layer, which serves as the skull's inner periosteum; (periosteal layer) 2. The deep layer; (meningeal layer) = dura mater proper Continuous through the foramen magnum - with the dura mater of the spinal cord. The two layers are closely united except - along certain lines, where they separate - to form venous sinuses Folds of dura mater • The meningeal layer Folded inwards as 4 septa between part of the brain • These septi incompletely separate the brain into freely communicating parts The function of these septa is to restrict the rotatory displacement of the brain Superior sagittal sinus Dura mater (Dural venous sinus) Endosteal layer Meningeal layer Subdural space Coronal section of the upper part of the head Dura mater: Falx cerebri Sickle shaped double layer of dura mater, lying between cerebral hemispheres Attached anteriorly to crista galli Attached posteriorly to tentorium cerebelli Has a free inferior concave border that contains inferior sagittal sinus Upper convex margin encloses superior sagittal sinus )1Falx cerebri )2Tentorium cerebelli )4Diaphragma sellae )3Falx cerebelli Sagittal section showing the duramater Falx cerebelli is a small, sickle-shaped fold of dura mater that is attached to the internal occipital crest projects forward between the two cerebellar hemispheres. -

Powerpoint Handout: Lab 1, Part B: Dural Folds, Dural Sinuses, and Arterial Supply to Head and Neck

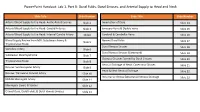

PowerPoint Handout: Lab 1, Part B: Dural Folds, Dural Sinuses, and Arterial Supply to Head and Neck Slide Title Slide Number Slide Title Slide Number Arterial Blood Supply to the Head: Aortic Arch Branches Slide 2 Innervation of Dura Slide 14 Arterial Blood Supply to the Head: Carotid Arteries Slide 3 Emissary Veins & Diploic Veins Slide 15 Arterial Blood Supply to the Head: Internal Carotid Artery Slide4 Cerebral & Cerebellar Veins Slide 16 Blood Supply Review from MSI: Subclavian Artery & Named Dural Folds Slide 5 Slide 17 Thyrocervical Trunk Dural Venous Sinuses Slide 18 Vertebral Artery Slide 6 Dural Venous Sinuses (Continued) Slide 19 Subclavian Steal Syndrome Slide 7 Osseous Grooves formed by Dural Sinuses Slide 20 Thyrocervical Trunk Slide 8 Venous Drainage of Head: Cavernous Sinuses Slide 21 Review: Suprascapular Artery Slide 9 Head & Neck Venous Drainage Slide 22 Review: Transverse Cervical Artery Slide 10 Intracranial Versus EXtracranial Venous Drainage Slide 23 Middle Meningeal Artery Slide 11 Meningeal Layers & Spaces Slide 12 Cranial Dura, Dural Folds, & Dural Venous Sinuses Slide 13 Arterial Blood Supply to the Head: Aortic Arch Branches The head and neck receive their blood supply from https://3d4medic.al/PXGmbxEt branches of the right and left common carotid and right and left subclavian arteries. • On the right side, the subclavian and common carotid arteries arise from the brachiocephalic trunk. • On the left side, these two arteries originate from the arch of the aorta. Arterial Blood Supply to the Head: Carotid Arteries On each side of the neck, the common carotid arteries ascend in the neck to the upper border of the thyroid cartilage (vertebral level C3/C4) where they divide into eXternal and internal carotid arteries at the carotid bifurcation. -

Shaken Baby Syndrome

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2005; 35:5–15 Paper © 2005 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh Shaken baby syndrome: theoretical and evidential controversies RA Minns Consultant Paediatric Neurologist, Royal Hospital for Sick Children and Child Life and Health, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland ABSTRACT Recent controversies have focused on whether shaking can injure the Published online September 2004 infant brain and if a diagnosis of SBS can be confidently made and distinguished (abbreviated version) from accidents (short falls) and non-traumatic conditions. Correspondence to RA Minns, This article reviews documented cases, animal, biomechanical, and computer- Consultant Paediatric Neurologist, GENERAL MEDICINE modelling evidence to support the contention that shaking alone without Royal Hospital for Sick Children and additional impact results in a rotational brain injury with tearing of cortical Child Life and Health, University of emissary veins, parenchymal shearing, cervico-medullary, and hypoxic-ischaemic Edinburgh 20 Sylvan Place, injury. Edinburgh, EH9 1UW While the terminology SBS is best avoided because it implies a mechanism in what tel. +44 (0)131 536 0637 is usually an unwitnessed injury, a more secure diagnosis of NAHI can be offered, fax. +44 (0)131 536 0821 with varying degrees of certainty, based on clinical, imaging, and ophthalmological findings after excluding conditions simulating these features. e-mail [email protected] The type of brain injury (inertial, contact, hypoxic-ischaemic) and the context in which it is sustained, may enable an opinion about whether the mechanism is consistent with either a purely rotational or rotational impact-deceleration injury, compressive, penetrative or other combined mechanism.