Upper Peninsula Community Health Needs Assessment 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Icss) for Children by Pihp/Cmhsp

ICSS FOR CHILDREN BY PIHP/CMHSP PHIP CMHSP Contact phone number Region 1: NorthCare Network Copper Country Mental Health Services 906-482-9404 (serving Baraga, Houghton, Keweenaw and Ontonagon) Gogebic County CMH Authority 906-229-6120 or 800-348-0032 Hiawatha Behavioral Health 800-839-9443 (serving Chippewa, Schoolcraft and Mackinac counties) Pathways Community Mental Health 888-728-4929 (serving Delta, Alger, Luce and Marquette counties) Northpointe Behavioral Health 800-750-0522 Region 2: Northern Michigan Regional Entity Northern Lakes Community Mental Health 833-295-0616 Authority (serving Crawford, Grand Traverse, Leelanau, Missaukee, Roscommon and Wexford counties) Au Sable Valley CMH services (serving Oscoda, 844-225-8131 Ogemaw, Iosco counties) Centra Wellness Network (Manistee Benzie 877-398-2013 CMH) North Country CMH (serving Antrium, 800-442-7315 Charlevoix, Cheboygan, Emmett, Kalkaska and Otsego) 01/29/2019 ICSS FOR CHILDREN BY PIHP/CMHSP Northeast Michigan CMH (serving Alcona, (989) 356-2161 Alpena, Montmorency and Presque Isle (800) 968-1964 counties) (800) 442-7315 during non-business hours Region 3: Lakeshore Regional Entity Allegan County CMH services 269-673-0202 or 888-354-0596 CMH of Ottawa County 866-512-4357 Network 180 616-333-1000 (serving Kent County) HealthWest During business hours: 231-720-3200 (serving Muskegon County) Non-business hours: 231-722-HELP West Michigan CMH 800-992-2061 (serving Oceana, Mason and Lake counties) Oceana: 231-873-2108 Mason: 231-845-6294 Lake: 231-745-4659 Region 4: Southwest Michigan Behavioral Health Barry County Mental Health Authority 269-948-8041 Berrien County Community Mental Health 269-445-2451 Authority 01/29/2019 ICSS FOR CHILDREN BY PIHP/CMHSP Branch County Mental Health Authority (aka 888-725-7534 Pines Behavioral Health) Cass County CMH Authority (aka Woodlands) 800-323-0335 Kalamazoo Community Mental Health and 269-373-6000 or 888-373-6200 Substance Abuse Services CMH of St. -

Michigan Medicaid Applied Behavior Analysis Services Provider Directory

Medicaid Applied Behavior Analysis Services Provider Directory October 2019 www.michigan.gov/autism Regional Prepaid Inpatient Health Plans Region 1: NorthCare Network ....................................................................................................................... 3 Region 2: Northern Michigan Regional Entity .............................................................................................. 5 Region 3: Lakeshore Regional Entity ............................................................................................................. 7 Region 4: Southwest Michigan Behavioral Health ...................................................................................... 10 Region 5: Mid-State Health Network .......................................................................................................... 12 Region 6: Community Mental Health Partnership of Southeast Michigan................................................. 17 Region 7: Detroit-Wayne Mental Health Authority .................................................................................... 20 Region 8: Oakland Community Health Network ......................................................................................... 22 Region 9: Macomb County Community Mental Health .............................................................................. 24 Region 10 Prepaid Inpatient Health Plan .................................................................................................... 25 Region 1: NorthCare Network 200 W. -

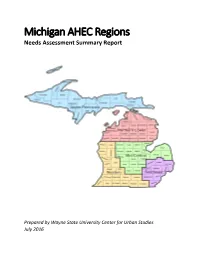

Michigan AHEC Regions Needs Assessment Summary Report

Michigan AHEC Regions Needs Assessment Summary Report Prepared by Wayne State University Center for Urban Studies July 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Southeast Michigan Region 1 AHEC Needs Assessment Mid‐Central Michigan Region 26 AHEC Needs Assessment Northern Lower Michigan Region 44 AHEC Needs Assessment Upper Peninsula Michigan Region 61 AHEC Needs Assessment Western Michigan Region 75 AHEC Needs Assessment Appendix 98 AHEC Needs Assessment Southeast Michigan Region Medically Underserved Summary Table 2 Medically Underserved Areas and Populations 3 Healthcare Professional Shortage Areas 4 Primary Care Physicians 7 All Clinically‐Active Primary Care Providers 8 Licensed Nurses 10 Federally Qualified Health Centers 11 High Schools 16 Health Needs 25 1 Medically Underserved Population Southeast Michigan AHEC Region Age Distribution Racial/Ethnic Composition Poverty Persons 65 Years of American Indian or Persons Living Below Children Living Below Persons Living Below Age and Older (%) Black (%) Alaska Native (%) Asian (%) Hispanic (%) Poverty (%) Poverty (%) 200% Poverty (%) Michigan 14.53 15.30 1.40 3.20 4.60 16.90 23.70 34.54 Genesee 14.94 22.20 1.50 1.40 3.10 21.20 32.10 40.88 Lapeer 14.68 1.50 1.00 0.60 4.30 11.60 17.20 30.48 Livingston 13.11 0.80 1.00 1.00 2.10 6.00 7.30 17.53 Macomb 14.66 10.80 1.00 3.90 2.40 12.80 18.80 28.72 Monroe 14.64 2.90 0.90 0.80 3.20 11.80 17.50 28.99 Oakland 13.90 15.10 1.00 6.80 3.60 10.40 13.80 22.62 St. -

OPENING of the Copper Country Intermediate School District Board

CCISD MINUTES –3/20/18 OPENING OF The Copper Country Intermediate School District Board of MEETING Education held its regular monthly meeting on Tuesday, March 20, 3/20/18 2018, at the Intermediate Service Center, 809 Hecla Street, Hancock, Michigan, beginning at 5:32 p.m. The meeting opened with the reciting of the “Pledge of Allegiance.” ROLL CALL MEMBERS PRESENT: Robert C. Tuomi, presiding; Nels S. Christopherson; Karen M. Johnson; Gale W. Eilola; Robert E. Loukus; and Lisa A. Tarvainen. MEMBER ABSENT: Robert L. Roy. ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF MEMBERS PRESENT: Katrina Carlson, Shawn Oppliger, Kristina Penfold, Mike Richardson and George Stockero. OTHER STAFF PRESENT: Jason Auel, Business Manager. GUEST PRESENT: Katrice Perkins, Reporter, Daily Mining Gazette. AGENDA & It was recommended by Superintendent George Stockero that the ADDENDUM submitted agenda, with addendum, be adopted as presented. It was moved by Mr. Loukus and seconded by Mrs. Tarvainen to adopt the agenda, with addendum, as presented. All yeas; motion carried. APPROVE It was recommended by Superintendent George Stockero that the MINUTES submitted minutes of the regular meeting of February 20, 2018, be 2/20/18 approved as presented. It was moved by Mrs. Johnson and seconded by Mr. Eilola to approve the minutes of the regular monthly meeting of February 20, 2018, as presented. All yeas; motion carried. APPROVE It was recommended by Business Manager Jason Auel and FINANCIAL Superintendent George Stockero that the financial statements be STATEMENTS accepted as presented. It was moved by Mr. Loukus and seconded by Mrs. Johnson to accept the financial statements as presented. All yeas; motion carried. -

Michigan's Copper Country" Lets You Experience the Require the Efforts of Many People with Different Excitement of the Discovery and Development of the Backgrounds

Michigan’s Copper Country Ellis W. Courter Contribution to Michigan Geology 92 01 Table of Contents Preface .................................................................................................................. 2 The Keweenaw Peninsula ........................................................................................... 3 The Primitive Miners ................................................................................................. 6 Europeans Come to the Copper Country ....................................................................... 12 The Legend of the Ontonagon Copper Boulder ............................................................... 18 The Copper Rush .................................................................................................... 22 The Pioneer Mining Companies................................................................................... 33 The Portage Lake District ......................................................................................... 44 Civil War Times ...................................................................................................... 51 The Beginning of the Calumet and Hecla ...................................................................... 59 Along the Way to Maturity......................................................................................... 68 Down the South Range ............................................................................................. 80 West of the Ontonagon............................................................................................ -

Houghton/Hancock to Calumet/Laurium Baraga/L'anse

Road Network d R KEARSARGE Where to Ride Bicycle Safety Map Information Before You Use This Map n Wide outside lane w Vehicle Traffic Volume to Map produced by: $5.00 or paved shoulder le Cr b se Be predictable and act like a vehicle VALUE u S On the Road: This map has been developed by the Western Upper o mith Ave h um e r Western Upper Peninsula Heavy (AADT above 10,000) ght Bicyclists on public roadways have the same rights and B au Bicycles are permitted on all Michigan highways and Peninsula Planning & Development Region as an aid Sl Planning & Development Region roads EXCEPT limited access freeways or unless other- responsibilities as automobile drivers, and are subject to to bicyclists and is not intended to be a substitute for a Medium (AADT 2,500 - 10,000) T d M a ayflower R the same state laws and ordinances. 326 Shelden Ave., P.O. Box 365 R m wise posted. Bicycles are allowed on all road systems person’s use of reasonable care. The user of this map a ck d Houghton, Michigan 49931 C r a a ra Centennial including those in State Forests, State Parks, National bears full responsibility for his or her own safety. c Light (AADT under 2,500) lu a m k 906-482-7205, Fax 906-482-9032 d Always wear an approved helmet m Creek e Heights W A s R Forests, and National Parks. WUPPDR makes no express or implied guarantee as t Wa m e y l a Ta g a o www.wuppdr.org d i Always have your helmet fitted and adjusted properly. -

ERF Funding Plan by County

Emergency Relief Grant Program Funding Plan Organization Name County Grant Award Upper Peninsula Arts and Culture Alliance Alger $3,000 Saugatuck Center for the Arts Allegan $3,000 Besser Museum Alpena $2,500 Thornapple Arts Barry $3,000 Historic Masonic Temple Bay City Bay $3,000 Acorn Center for the Performing Arts Berrien $3,000 Buchanan Art Center Berrien $3,000 Heritage Museum and Cultural Center Berrien $3,000 Krasl Art Center Berrien $3,000 Long Haul Productions Berrien $3,000 Southwest Michigan Symphony Orchestra Berrien $3,000 Tibbits Opera House Branch $3,000 Binder Park Zoo Calhoun $3,000 Bohm Theatre Calhoun $3,000 Brass Band of Battle Creek Calhoun $3,000 Eastend Studio & Gallery Calhoun $3,000 Great Escape Calhoun $3,000 Kingman Museum Calhoun $3,000 Beaver Island Cultural Arts Association Charlevoix $3,000 Patrons of the Arts in Rural Communities Charlevoix $3,000 History Center of Cheboygan County Cheboygan $1,000 Icebreaker Mackinaw Museum Ship Cheboygan $3,000 Michigan Museums Association Cheboygan $3,000 Clinton County Arts Council Clinton $3,000 Bonifas Arts Center Delta $3,000 Blissfest Music Organization Emmet $3,000 Crooked Tree Arts Center Emmet $3,000 African Drum & Dance Parent Association Genesee $3,000 El Ballet Folklorico Estudiantil Genesee $2,834 Fenton Arts Council Genesee $1,000 Fenton Community Orchestra Genesee $3,000 Flint Children's Museum Genesee $3,000 Flint Institute of Music Genesee $3,000 Floyd J McCree Theatre Genesee $3,000 Red Ink Flint Genesee $3,000 Shop Floor Theatre Company Genesee $3,000 -

LAKE GOGEBIC TIMES Printed Annually Since 1990 by the Lake Gogebic Area Chamber of Commerce

★ 2019 Lake Gog ebic Times Vacation Guide For Michigan’s Upper Peninsula’s FFREEREE Largest Lake and Surrounding Western U.P. Area Th e Lake Gogebic Area Presorted Chamber of Commerce Standard P.O. Box 114 U.S. Postage Bergland, Michigan 49910-0114 PAID Phone: 1-888-GOGEBIC (464-3242) Ashland, WI www.lakegogebicarea.com FFREEREE Snowmobile & Lake Maps Inside FOUR Bear’sBear’s SEASON NINE PINES RESORT N9426 State Hwy M64 • Marenisco, MI • 49947 • 906-842-3361 LAKE GOGEBIC RENTALS GUIDE SERVICES • Four Season Cabins • Black Bear • Pontoons Hunts • Boats • Lake Gogebic • Motors Fishing • Canoes • Kayaks • Swim Tube • Licenses • Skis • Permits • Ice Fishing • Full Service Equipment Bait Shop WWW.NINEPINESRESORT.COM LAKE GOGEBIC TIMES Printed Annually Since 1990 by The Lake Gogebic Area Chamber of Commerce Editors: Mary Lou Driesenga, Bonnie Trolla, Patty Urbanski U.P. Pro Rodeo in Iron River - The only Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association Rodeo Ads: Mary Lou Driesenga in Michigan, July 18-20. The U.P. Championship Rodeo is an action-packed weekend featur- ing 3 performances with bull and bronco riders, cattle roping, barrel racing, steer wrestling, 25,000 copies of the Lake Gogebic Times are being published this year for complimentary Rodeo Queen pageant, & more www.upprorodeo.com. distribution throughout Michigan Welcome Centers, at Sport Shows throughout MI, WI, MN, IO and many businesses in the Western U.P. We also offer the paper to you, in print- So peaceful - Fall day fi shing on Lake Gogebic taken by Phil Tegner able context on the Lake Gogebic Area Chamber of Commerce website. Articles, informa- tion and photos suitable for publication are solicited and can be sent to the chamber address. -

Copper Country Aerial Photographs. MS-967

Copper Country Aerial Photographs. MS-967 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 29, 2019. English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections 1400 Townsend Drive Houghton 49931 [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.mtu.edu/mtuarchives/ Copper Country Aerial Photographs. MS-967 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 - Page 2 - Copper Country Aerial Photographs. MS-967 Summary Information Repository: Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections Title: Copper Country Aerial Photographs. ID: MS-967 -

Guide to Researching Michigan Copper Mining Companies

Guide To Researching Michigan Copper Mining Companies Contents Mining Company Annual Reports Published Histories -- General Histories -- Histories of Specific Mining Companies Published Reference Works and Governmental Reports -- Michigan Mineral Statistic -- Copper Handbook / Mines Register -- USGS Professional Paper 144 Magazine / Journal Articles -- Library Collection -- Lake Superior Mining Institute -- Institute on Lake Superior Geology Newspapers C&H Abstract Files Copper Country Vertical Files Mining Company Manuscript Collections Tax / Property Records Cartographic Material (Maps) Photographic Images Mining Company Publications Most Michigan copper mining companies were public stock corporations and as such were required to publish annual reports to their shareholders. The Michigan Tech Archives has one of the most comprehensive collections of published corporate reports for the region. Annual reports usually include capitalization, executive, development, production, profit, and construction details. Most also include a narrative report from the local superintendent or agent with specific information of development work conducted on a year-by-year basis. Researchers should remain critical of the information, particularly financial reporting, contained in these resources; it is not uncommon to find these published reports putting a positive spin on years of lackluster performance. Corporate annual reports are cataloged on the Library's online catalog, Voyager. PUBLISHED HISTORIES General Histories A wide variety of titles provide general background to Copper Country history and the development of copper mining in the Keweenaw Peninsula. Included are older titles, such as History of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan (1883, F572.N8 H67), which provide contemporary accounts of mines and mining companies, and modern publications, such as Lankton's Cradle to Grave (1991, HD 9539.C7 U548) and Thurner's Strangers and 1 Sojourners (1994, F572.K43), which provide academic analysis of the social and technological development of Keweenaw mines and communities. -

In the Shadows of the Shafts

In the Shadows of the Shafts Remembering mining in the Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan in 1972-1978 Meeri Karoliina Kataja University of Helsinki Faculty of Social Sciences Political History Master’s Thesis May 2020 Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Faculty of Social Sciences Tekijä – Författare – Author Meeri Karoliina Kataja Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title In the Shadows of the Shafts: Remembering Mining in the Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan in 1972–1978 Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Political History Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä – Sidoantal – Number of pages Master’s Thesis May 2020 89 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Copper mining has characterized the Keweenaw Peninsula, in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, from the 1840s. The industry that lasted in the region over 100 years has been profoundly studied, but the industrial heritage has received less attention. This study is interested in the memory of mining and in the future prospects of locals right after the closure of the mines in 1969. This study is data-driven, using the interviews conducted within the Finnish Folklore and Social Change in the Great Lakes Mining Region Oral History Project by the Finlandia University in 1973-1978. The method is thematic analysis, which is used to identify, analyze and report themes related to talk on the mines, mining, the 1913 Strike, and the future. Two main themes are negative and positive talk. Within negative talk, three sub-themes are identified: insecurity, disappointment and loss. There is more negative talk within the data set, especially because of the 1913 Strike and the Italian Hall Disaster, which were still commonly remembered. -

Catalog Is Published for Informational Purposes; However, the Information Is Not to Be Considered As an Irrevocable Contract Between the Student and the College

Higher Learning Commission E4946 Jackson Road Ironwood, MI 49938 - Telephone 906/932-4231 800/682-5910 Toll Free gogebic.edu This catalog is published for informational purposes; however, the information is not to be considered as an irrevocable contract between the student and the college. While this catalog was prepared on the basis of the best information available at the time of publication, all information including statements of tuition and fees, curriculum and course offerings, admissions, graduation requirements, and other matters within its control is subject to change without notice or obligation. Please visit our website at Gogebic.edu for the most up to date catalog information. It is the policy of the college that no persons on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin or ancestry, age, sex, marital status, or disability, political affiliation or belief shall be discriminated against, excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise subjected to discrimination in any program or activity for which the college is responsible or for which it receives federal financial assistance from the Department of Education. 1 Welcome to Gogebic Community College! From the main campus in Ironwood, Michigan and the Copper Country Center in Houghton, Michigan, the GCC community welcomes you! Whether your goal is transfer to a four-year institution, to advance your career through attainment of a technical certificate or degree in one of many high demand fields, personal enrichment or workforce development, Gogebic Community College is ready to meet your individual needs. Situated in Michigan’s majestic Upper Peninsula with year-round adventure and attractions, you will be amazed by all of the opportunities here.