In the Shadows of the Shafts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Italian Hall Tragedy, 1913: a Hundred Years of Remediated Memories

chapter �� The Italian Hall Tragedy, 1913: A Hundred Years of Remediated Memories Anne Heimo On Christmas Eve 1913 seventy-three people were crushed to death during the 1913–1914 Copper Strike in the small township of Calumet on the Keweenaw Peninsula, Upper Michigan. On Christmas Eve the local Women’s Auxiliary of the Western Federation of Miners (wfm) had arranged a party for the strikers’ families at the local Italian hall. At some point in the evening someone was heard to shout ‘fire’ and as people rushed to get out of the building they were hauled down the stairs and crushed to death. Sixty-three of the victims were children. There was no fire. Later on this tragic event became to be known as ‘The Italian Hall tragedy’, ‘The Italian Hall disaster’ or the ‘1913 Massacre,’ and it continues to be the one most haunting event in the history of the Copper Country. As a folklorist and oral historian, I am foremost interested in the history and memory practices of so called ordinary people in everyday situations and how they narrate about the past and events and experiences they find memorable and worth retelling. When first hearing about the tragedy a few years ago, I could not help noticing that it had all the elements for keeping a story alive. The tragedy was a worker’s conflict between mining companies and miners, which resulted in the death of many innocent people, mainly children. Although the tragedy was investigated on several occasions, no one was found responsible for the deaths, and the case remains unsolved to this day. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form 1

NFS Form 10-900 (3-82) OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NFS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register*Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name__________________ historic Quincy Mining Company Historic District and or common 2. Location street & number from Portage Lake to the brow of Quincy Hill not for publication city, town Hancock _JL vicinity of state Michigan code county Houghton code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Prestent Use _ X. district public X occupied agriculture X museum building(s) X private unoccupied _ X. commercial __ park structure both work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered .. yes: unrestricted X industrial __ transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Please see continuation sheets street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Houghton County Courthouse street & number city, town Houghton state Michigan 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Historic American Engineering Records this property been determined eligible? __ yes .X_ no National Register of Historic Places nomination for #2 Shaft and Hoist Houses date 1978; 1970_______________________________-^- federal __ state __ county __ local depository for survey records Library of Congress; National Register of Historic Places______ _ city, town Washington, D.C. state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered original site _X_good ruins altered moved date fair unexposed Some historic buildings are now in ruins. -

(Icss) for Children by Pihp/Cmhsp

ICSS FOR CHILDREN BY PIHP/CMHSP PHIP CMHSP Contact phone number Region 1: NorthCare Network Copper Country Mental Health Services 906-482-9404 (serving Baraga, Houghton, Keweenaw and Ontonagon) Gogebic County CMH Authority 906-229-6120 or 800-348-0032 Hiawatha Behavioral Health 800-839-9443 (serving Chippewa, Schoolcraft and Mackinac counties) Pathways Community Mental Health 888-728-4929 (serving Delta, Alger, Luce and Marquette counties) Northpointe Behavioral Health 800-750-0522 Region 2: Northern Michigan Regional Entity Northern Lakes Community Mental Health 833-295-0616 Authority (serving Crawford, Grand Traverse, Leelanau, Missaukee, Roscommon and Wexford counties) Au Sable Valley CMH services (serving Oscoda, 844-225-8131 Ogemaw, Iosco counties) Centra Wellness Network (Manistee Benzie 877-398-2013 CMH) North Country CMH (serving Antrium, 800-442-7315 Charlevoix, Cheboygan, Emmett, Kalkaska and Otsego) 01/29/2019 ICSS FOR CHILDREN BY PIHP/CMHSP Northeast Michigan CMH (serving Alcona, (989) 356-2161 Alpena, Montmorency and Presque Isle (800) 968-1964 counties) (800) 442-7315 during non-business hours Region 3: Lakeshore Regional Entity Allegan County CMH services 269-673-0202 or 888-354-0596 CMH of Ottawa County 866-512-4357 Network 180 616-333-1000 (serving Kent County) HealthWest During business hours: 231-720-3200 (serving Muskegon County) Non-business hours: 231-722-HELP West Michigan CMH 800-992-2061 (serving Oceana, Mason and Lake counties) Oceana: 231-873-2108 Mason: 231-845-6294 Lake: 231-745-4659 Region 4: Southwest Michigan Behavioral Health Barry County Mental Health Authority 269-948-8041 Berrien County Community Mental Health 269-445-2451 Authority 01/29/2019 ICSS FOR CHILDREN BY PIHP/CMHSP Branch County Mental Health Authority (aka 888-725-7534 Pines Behavioral Health) Cass County CMH Authority (aka Woodlands) 800-323-0335 Kalamazoo Community Mental Health and 269-373-6000 or 888-373-6200 Substance Abuse Services CMH of St. -

Michigan Medicaid Applied Behavior Analysis Services Provider Directory

Medicaid Applied Behavior Analysis Services Provider Directory October 2019 www.michigan.gov/autism Regional Prepaid Inpatient Health Plans Region 1: NorthCare Network ....................................................................................................................... 3 Region 2: Northern Michigan Regional Entity .............................................................................................. 5 Region 3: Lakeshore Regional Entity ............................................................................................................. 7 Region 4: Southwest Michigan Behavioral Health ...................................................................................... 10 Region 5: Mid-State Health Network .......................................................................................................... 12 Region 6: Community Mental Health Partnership of Southeast Michigan................................................. 17 Region 7: Detroit-Wayne Mental Health Authority .................................................................................... 20 Region 8: Oakland Community Health Network ......................................................................................... 22 Region 9: Macomb County Community Mental Health .............................................................................. 24 Region 10 Prepaid Inpatient Health Plan .................................................................................................... 25 Region 1: NorthCare Network 200 W. -

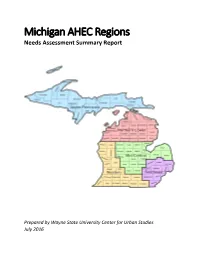

Michigan AHEC Regions Needs Assessment Summary Report

Michigan AHEC Regions Needs Assessment Summary Report Prepared by Wayne State University Center for Urban Studies July 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Southeast Michigan Region 1 AHEC Needs Assessment Mid‐Central Michigan Region 26 AHEC Needs Assessment Northern Lower Michigan Region 44 AHEC Needs Assessment Upper Peninsula Michigan Region 61 AHEC Needs Assessment Western Michigan Region 75 AHEC Needs Assessment Appendix 98 AHEC Needs Assessment Southeast Michigan Region Medically Underserved Summary Table 2 Medically Underserved Areas and Populations 3 Healthcare Professional Shortage Areas 4 Primary Care Physicians 7 All Clinically‐Active Primary Care Providers 8 Licensed Nurses 10 Federally Qualified Health Centers 11 High Schools 16 Health Needs 25 1 Medically Underserved Population Southeast Michigan AHEC Region Age Distribution Racial/Ethnic Composition Poverty Persons 65 Years of American Indian or Persons Living Below Children Living Below Persons Living Below Age and Older (%) Black (%) Alaska Native (%) Asian (%) Hispanic (%) Poverty (%) Poverty (%) 200% Poverty (%) Michigan 14.53 15.30 1.40 3.20 4.60 16.90 23.70 34.54 Genesee 14.94 22.20 1.50 1.40 3.10 21.20 32.10 40.88 Lapeer 14.68 1.50 1.00 0.60 4.30 11.60 17.20 30.48 Livingston 13.11 0.80 1.00 1.00 2.10 6.00 7.30 17.53 Macomb 14.66 10.80 1.00 3.90 2.40 12.80 18.80 28.72 Monroe 14.64 2.90 0.90 0.80 3.20 11.80 17.50 28.99 Oakland 13.90 15.10 1.00 6.80 3.60 10.40 13.80 22.62 St. -

Theatrical Entertainment, Social Halls, Industry and Community: Houghton County, Michigan, 1837-1916

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: _Ishpeming Main Street Historic District_____________ Other names/site number: _N/A_________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: _N/A______________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: _Generally, Main Street between Front and Division Streets including selected contiguous properties on Front Street and East and West Division Streets_ City or town: _Ishpeming___ State: _Michigan___ County: _Marquette __ Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ request -

OPENING of the Copper Country Intermediate School District Board

CCISD MINUTES –3/20/18 OPENING OF The Copper Country Intermediate School District Board of MEETING Education held its regular monthly meeting on Tuesday, March 20, 3/20/18 2018, at the Intermediate Service Center, 809 Hecla Street, Hancock, Michigan, beginning at 5:32 p.m. The meeting opened with the reciting of the “Pledge of Allegiance.” ROLL CALL MEMBERS PRESENT: Robert C. Tuomi, presiding; Nels S. Christopherson; Karen M. Johnson; Gale W. Eilola; Robert E. Loukus; and Lisa A. Tarvainen. MEMBER ABSENT: Robert L. Roy. ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF MEMBERS PRESENT: Katrina Carlson, Shawn Oppliger, Kristina Penfold, Mike Richardson and George Stockero. OTHER STAFF PRESENT: Jason Auel, Business Manager. GUEST PRESENT: Katrice Perkins, Reporter, Daily Mining Gazette. AGENDA & It was recommended by Superintendent George Stockero that the ADDENDUM submitted agenda, with addendum, be adopted as presented. It was moved by Mr. Loukus and seconded by Mrs. Tarvainen to adopt the agenda, with addendum, as presented. All yeas; motion carried. APPROVE It was recommended by Superintendent George Stockero that the MINUTES submitted minutes of the regular meeting of February 20, 2018, be 2/20/18 approved as presented. It was moved by Mrs. Johnson and seconded by Mr. Eilola to approve the minutes of the regular monthly meeting of February 20, 2018, as presented. All yeas; motion carried. APPROVE It was recommended by Business Manager Jason Auel and FINANCIAL Superintendent George Stockero that the financial statements be STATEMENTS accepted as presented. It was moved by Mr. Loukus and seconded by Mrs. Johnson to accept the financial statements as presented. All yeas; motion carried. -

Michigan's Copper Country" Lets You Experience the Require the Efforts of Many People with Different Excitement of the Discovery and Development of the Backgrounds

Michigan’s Copper Country Ellis W. Courter Contribution to Michigan Geology 92 01 Table of Contents Preface .................................................................................................................. 2 The Keweenaw Peninsula ........................................................................................... 3 The Primitive Miners ................................................................................................. 6 Europeans Come to the Copper Country ....................................................................... 12 The Legend of the Ontonagon Copper Boulder ............................................................... 18 The Copper Rush .................................................................................................... 22 The Pioneer Mining Companies................................................................................... 33 The Portage Lake District ......................................................................................... 44 Civil War Times ...................................................................................................... 51 The Beginning of the Calumet and Hecla ...................................................................... 59 Along the Way to Maturity......................................................................................... 68 Down the South Range ............................................................................................. 80 West of the Ontonagon............................................................................................ -

Break Down the Nature-Culture Divide in Parks

770 The Journal of American History December 2013 (p. 15). The authors respond by offering a litany of fixes: break down the nature-culture divide in parks; highlight the open-ended nature of the past; embrace controversy and dis- parate understandings of history; learn from the public; work more closely with scholars in the academy. These suggestions could, if implemented, usher in a new era for history in the . In the end, however, the agency finds itself in a state of ongoing organizational triage. Like so many other gears of the federal apparatus in recent years, the has faced massive budget cuts. And with the so-called sequester contracting rather than expanding funding, there appears to be little cause for optimism. Given the fiscal realities, one wonders if the has the resources necessary to stem the bleeding and embrace best historical practices— or if the ghost of George Hartzog will enjoy the last laugh. Ari Kelman Downloaded from University of California–Davis Davis, California doi: 10.1093/jahist/jat460 http://jah.oxfordjournals.org/ Keweenaw National Historic Park, Calumet, Mich. http://www.nps.gov/kewe/index.htm. Permanent exhibition. Park established 1992. Permanent exhibition. “Risk and Resilience: Life in a Copper Mining Community” exhibit, opened 2011. 7,000 sq. ft. National Park Service, curatorial director; Krister Olmon, exhibit designer; Harvest Moon Studios, exhibit script. Permanent exhibition. Keweenaw Heritage Site at Quincy Mine no. 2, opened 1994. Quincy Mine Hoist Association, interpretation and mine tours. at Knox College on April 3, 2014 Permanent exhibition. Self-guided tours of downtown and industrial Calumet, opened 1992. -

Houghton/Hancock to Calumet/Laurium Baraga/L'anse

Road Network d R KEARSARGE Where to Ride Bicycle Safety Map Information Before You Use This Map n Wide outside lane w Vehicle Traffic Volume to Map produced by: $5.00 or paved shoulder le Cr b se Be predictable and act like a vehicle VALUE u S On the Road: This map has been developed by the Western Upper o mith Ave h um e r Western Upper Peninsula Heavy (AADT above 10,000) ght Bicyclists on public roadways have the same rights and B au Bicycles are permitted on all Michigan highways and Peninsula Planning & Development Region as an aid Sl Planning & Development Region roads EXCEPT limited access freeways or unless other- responsibilities as automobile drivers, and are subject to to bicyclists and is not intended to be a substitute for a Medium (AADT 2,500 - 10,000) T d M a ayflower R the same state laws and ordinances. 326 Shelden Ave., P.O. Box 365 R m wise posted. Bicycles are allowed on all road systems person’s use of reasonable care. The user of this map a ck d Houghton, Michigan 49931 C r a a ra Centennial including those in State Forests, State Parks, National bears full responsibility for his or her own safety. c Light (AADT under 2,500) lu a m k 906-482-7205, Fax 906-482-9032 d Always wear an approved helmet m Creek e Heights W A s R Forests, and National Parks. WUPPDR makes no express or implied guarantee as t Wa m e y l a Ta g a o www.wuppdr.org d i Always have your helmet fitted and adjusted properly. -

Keweenaw National Historical Park National Park Service Keweenaw Michigan U.S

Keweenaw National Historical Park National Park Service Keweenaw Michigan U.S. Department of the Interior The Keweenaw Peninsula of Upper Michigan was home to the world’s During the late 1800s the American Dream was sought by thousands and most abundant deposits of pure, elemental copper. It was also home to found by few on the Keweenaw, much like the rest of America. Working class the pioneers who met the challenges of nature and technology to coax it immigrants from around the world came to this copper region to improve from the ground and provide the raw material that spurred the American their lives, and in doing so, helped transform a young and growing nation Industrial Revolution. into a global powerhouse. The Rush for Copper Reports in 1843 of enormous copper The copper companies became known People found common interests in their By the late 1800s the company enjoyed direct more and more complex industrial reaffirmed the companies’ domination over deposits on the Keweenaw Peninsula worldwide as leaders in modern, dreams of a better life, fueled by a sense of a reputation as one of the nation’s best- technologies. The working class, however, the workers. A pall of bitterness, resent- spawned one of our nation’s earliest scientific mining technology. Keweenaw optimism and a persistent desire to succeed. known business enterprises. Between 1867 grew restless under an increasingly imper- ment, and social polarization descended mining rushes, preceding the famed copper even affected the outcome of the Their struggle to adapt to profound and 1884, it produced one-half of the coun- sonal style of management and supervision.