Break Down the Nature-Culture Divide in Parks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theatrical Entertainment, Social Halls, Industry and Community: Houghton County, Michigan, 1837-1916

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Michigan's Copper Country" Lets You Experience the Require the Efforts of Many People with Different Excitement of the Discovery and Development of the Backgrounds

Michigan’s Copper Country Ellis W. Courter Contribution to Michigan Geology 92 01 Table of Contents Preface .................................................................................................................. 2 The Keweenaw Peninsula ........................................................................................... 3 The Primitive Miners ................................................................................................. 6 Europeans Come to the Copper Country ....................................................................... 12 The Legend of the Ontonagon Copper Boulder ............................................................... 18 The Copper Rush .................................................................................................... 22 The Pioneer Mining Companies................................................................................... 33 The Portage Lake District ......................................................................................... 44 Civil War Times ...................................................................................................... 51 The Beginning of the Calumet and Hecla ...................................................................... 59 Along the Way to Maturity......................................................................................... 68 Down the South Range ............................................................................................. 80 West of the Ontonagon............................................................................................ -

Keweenaw Guide Summer 2012 Issue

National Park Service Park News U.S. Department of the Interior The official newspaper of Keweenaw National Historical Park and the Keweenaw Heritage Sites The Keweenaw Guide Summer 2012 Issue Welcome from the Keweenaw Seasons Park Superintendent Welcome to Keweenaw IF You’re lIKE MOST PEOPLE You’re prOBABLY READING THIS Visitors who do their homework will find many of the Keweenaw National Historical Park, article during a beautiful Copper Country summer month. Keween- Heritage Sites are open to the public in the winter, often by means one of 397 units in your aw National Historical Park and its 19 Heritage Sites typically receive of self-guided grounds tours. Popular winter activities include cross National Park System. the bulk of their visitors in July and August, when days are usually country skiing, snowshoeing and snowmobiling. Travel by snow- This year marks the park’s warm and sunny. The Copper Country is full of adventures waiting mobile allows for much of the same access to sites as traveling by 20th anniversary. The to be experienced during the summer. Have you ever wondered car does. All winter recreationists are asked to be extra mindful in park was established by about the adventures that fall, winter, and spring have to offer? the winter months of safety hazards and of protecting our treasured an action of Congress signed by President cultural resources. Deep snow often obscures holes, historic struc- George Bush on October 27, 1992, and our Autumn may be one of the best times of year to be in the Copper tures and artifacts, so please stay on designated trails. -

In the Shadows of the Shafts

In the Shadows of the Shafts Remembering mining in the Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan in 1972-1978 Meeri Karoliina Kataja University of Helsinki Faculty of Social Sciences Political History Master’s Thesis May 2020 Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Faculty of Social Sciences Tekijä – Författare – Author Meeri Karoliina Kataja Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title In the Shadows of the Shafts: Remembering Mining in the Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan in 1972–1978 Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Political History Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä – Sidoantal – Number of pages Master’s Thesis May 2020 89 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Copper mining has characterized the Keweenaw Peninsula, in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, from the 1840s. The industry that lasted in the region over 100 years has been profoundly studied, but the industrial heritage has received less attention. This study is interested in the memory of mining and in the future prospects of locals right after the closure of the mines in 1969. This study is data-driven, using the interviews conducted within the Finnish Folklore and Social Change in the Great Lakes Mining Region Oral History Project by the Finlandia University in 1973-1978. The method is thematic analysis, which is used to identify, analyze and report themes related to talk on the mines, mining, the 1913 Strike, and the future. Two main themes are negative and positive talk. Within negative talk, three sub-themes are identified: insecurity, disappointment and loss. There is more negative talk within the data set, especially because of the 1913 Strike and the Italian Hall Disaster, which were still commonly remembered. -

Portals to the Past: a Bibliographical and Resource Guide to Michiganâ

Northern Michigan University NMU Commons Books 2017 Portals to the Past: A Bibliographical and Resource Guide to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula Russel Magnaghi Northern Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.nmu.edu/facwork_book Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Magnaghi, Russel, "Portals to the Past: A Bibliographical and Resource Guide to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula" (2017). Books. 27. http://commons.nmu.edu/facwork_book/27 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. CENTER FOR UPPER PENINSULA STUDIES Portals to the Past: A Bibliographical and Resource Guide to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula Russell M. Magnaghi 2017 Revised edition Portals to the Past: A Bibliographical and Resource Guide to 2017 Michigan’s Upper Peninsula TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS....................................................................................................................... 2 REVISED INTRODUCTION FOR SECOND EDITION ............................................................................ 6 GENERAL OVERVIEW ....................................................................................................................... 8 AGRICULTURE ............................................................................................................................... 13 AMERICAN PRESENCE, 1796-1840 -

MS-080 — Copper Range Company Records

Copper Range Company Records MS-080 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 22, 2018. English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections 1400 Townsend Drive Houghton 49931 [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.mtu.edu/mtuarchives/ Copper Range Company Records MS-080 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 5 Biographical / Historical ................................................................................................................................ 6 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 9 Related Materials ......................................................................................................................................... 10 Controlled Access Headings ........................................................................................................................ 10 MARC Export ............................................................................................................................................. -

Newspaper Reports of Calumet's Italian Hall Disaster

Upper Country: A Journal of the Lake Superior Region Volume 4 Article 4 2016 No News Is Good News: Newspaper Reports of Calumet’s Italian Hall Disaster Allie Penn Wayne State University, graduate student, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/upper_country Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, Labor History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Penn, Allie (2016) "No News Is Good News: Newspaper Reports of Calumet’s Italian Hall Disaster," Upper Country: A Journal of the Lake Superior Region: Vol. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://commons.nmu.edu/upper_country/vol4/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Peer-Reviewed Series at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Upper Country: A Journal of the Lake Superior Region by an authorized editor of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Penn: No News Is Good News: Newspaper Reports of Calumet’s Italian Hall Disaster No News Is Good News: Newspaper Reports of Calumet’s Italian Hall Disaster Allie Penn “Take a trip with me in 1913, To Calumet, Michigan, in the copper country. I will take you to a place called Italian Hall, Where the miners are having their big Christmas ball.” 1 Singer Woody Guthrie wrote “1913 Massacre” almost forty years after the disaster occurred. When he crooned the above lyrics about the 1913-14 Copper Country Strike in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, he wanted to memorialize the worker’s unionization movement and the tragedy of the Italian Hall Disaster. -

Upper Peninsula History Conference

64TH ANNUAL JUNE 28-30, 2013 • HOUGHTON, MI Upper Peninsula History Conference Hosted and sponsored by: Michigan Technological University Archives Also sponsored by: and Copper Country Historical Collections Houghton County Historical Society Keweenaw National Historical Park Quincy Mine Hoist Association For details and registration, visit www.hsmichigan.org or call toll-free (800) 692-1828 Friday, June 28 9 AM-NOON Pre-Conference Workshop Pre-Conference Workshop Promotion and Marketing for Small Heritage Organizations Friday 9 AM Carnegie Museum, 105 Huron St. (northeast corner of Huron and Montezuma), Houghton. Promotion and Marketing for (See box at right) Small Heritage Organizations 12-4 PM Registration Erik Nordberg Magnuson Franklin Square Inn Lobby, 820 Shelden Ave., Houghton Executive Director, Michigan Humanities Council 2-4:30 PM Concurrent Pre-Conference Tours $25 with conference registration* NOTE: All tours require participants to self-drive to the departure loca- tion listed with each tour below. This workshop will review the basics of promotion and marketing for smaller agencies, particularly those with Tour 1: NPS Calumet Visitor Center/ Italian Hall limited staffing. Learn how to develop simple promotional 98 Fifth St., Calumet tools like informational cards, flyers, and posters. Participants will self-drive to the National Park Service Calumet Visitor Center Concrete examples of effective media releases will be for a special tour, which will conclude with a visit to the site of the Italian Hall presented, as well as the places to send them, and Memorial. $15 proven strategies to engage print, radio, and television media to promote your programs and events. Includes Tour 2: Quincy Smelter and the Houghton County handouts and other takeaways. -

Calumet Explorer

Swedetown Rd. Mine St. Eighth St. For more information on the businesses and attractions Wedge St. located in downtown Calumet, visit mainstreetcalumet.com. Temple St. Scott St. Portland St. Oak St. Elm St. Pine St. Seventh St. Sixth St. Sixth St. Extension Fifth St. Boundary Rd. Mine St. Fourth St. Free Public Parking Agassiz Park Fourth St. P a r k Av e. Lake Linden Ave. Depot St. Red Jacket Rd. Third St. Rockland St. Second St. Calumet Pine St. Hecla St. Lake SchoolsCLK Third St. Laurium St. Waterworks St. Mine St. Boundary St. Osceola St. Hecla St. Kearsarge St. Third St. First / School St. Rockland St. Old Colony Rd. Colony Old Second St. Tamarack St. Pewabic St. 33 - Keweenaw Heritage Center* 49 - Keweenaw National Historical Park 64 - Calumet Waterworks Park “Bucky’s” Shopping Dining Headquarters 1 - Artis Books & Antiques & Uptown 19 - Cafe Rosetta 34 - Keweenaw National Historical Park 65 - Main Street Farmers Market Galleries Visitor’s Center at the Union Building 66 - Calumet Golf Club 20 - Fifth & Elm Coffeehouse Churches 2 - Galerie Boheme 35 - Calumet Colosseum & Guts Frisbee 67 - Copper Country Curling Club 21 - Jim’s Pizza & Family Restaurant Hall of Fame 50 - Saint Paul the Apostle Catholic 3 - Cross Country Sports 22 - Michigan House Café & Red Jacket Church 36 - AmericInn of Calumet Services 4 - Hahn Hammered Copper Brewing Co. 51 - Christ Episcopal Church 37 - Copper Country Firefighters History 68 - Aspirus Keweenaw Hospital and 5 - The Paige Wiard Gallery 23 - Carmelita’s - A Southwestern Grille Museum* 52 - Keweenaw -

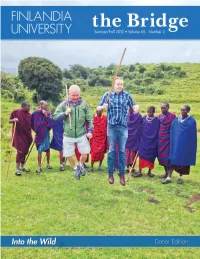

2012 Fall-Summer Bridge

From the President PHILIP JOHNSON his Bridge issue features three stories about Finlandia students venturing “into the wild.” “Wild,” of course, does not need to be an exotic location. We all venture “into the wild” whenever we choose to exchange the familiar for the unfamiliar, the comfortable for the uncomfortable, the known for the unknown. Such choosing calls for courage. At her best, Finlandia creates for her students opportunities that are ripe for discovering and exercising courageous learning and living. This past summer, I paused to reflect on my first five years at Finlandia, which prompted me to re-visit my September 2007 inauguration speech (printed in part below). Courage was its centerpiece, and courageous learning and living— then and now––belongs to the Finlandia experience for our students, as well as to all of us who serve them. I believe the presidency of any university such as ours calls for courage. And those of you here today who have walked with this place over the decades know this, as well. Yet, it is the courage embedded in our mission and embodied in our students that calls for our attention today. I have said this many times: it was Finlandia’s mission and identity that lured me, though reluctantly at first, to consider the presidency. It takes courage to live with a mission at all these days, I think. I’ve been tempted, even early on, to say, “Let’s cut to the bottom line: what’s marketable and makes money?” Why mission? Mission statements, vision statements, the kind that fill the first two pages of our, and most, academic catalogs, often get in the way, to be frank. -

Arts and Sustainability in Calumet, Michigan

sustainability Article Boom, Bust and Beyond: Arts and Sustainability in Calumet, Michigan Richelle Winkler 1,*,†, Lorri Oikarinen 2,†, Heather Simpson 3, Melissa Michaelson 1 and Mayra Sanchez Gonzalez 4 1 Department of Social Sciences, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI 49931, USA; [email protected] 2 Calumet, MI 49913, USA; [email protected] 3 Center for Student Success, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI 49931, USA; [email protected] 4 Environmental and Energy Policy Program, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI 49931, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-906-487-1886 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Academic Editor: Tan Yigitcanlar Received: 4 January 2016; Accepted: 11 March 2016; Published: 21 March 2016 Abstract: Cycles of boom and bust plague mining communities around the globe, and decades after the bust the skeletons of shrunken cities remain. This article evaluates strategies for how former mining communities cope and strive for sustainability in the decades well beyond the bust, using a case study of Calumet, Michigan. In 1910, Calumet was at the center of the mining industry in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, but in the century since its peak, mining employment steadily declined until the last mine closed in 1968, and the population declined by over 80%. This paper explores challenges, opportunities, and progress toward sustainability associated with arts-related development in this context. Methods are mixed, including observation, -

MTU-212 — Larry Lankton Collection

Larry Lankton Collection This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on 2018-07-02 Finding aid written in English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections 1400 Townsend Drive Houghton, , 49931 [email protected] http://www.lib.mtu.edu/mtuarchives/ Larry Lankton Collection Table Of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Conditions Governing Use ........................................................................................................................ 3 Conditions Governing Access .................................................................................................................. 3 Language of Material ................................................................................................................................ 3 Scope and Contents ................................................................................................................................... 3 Biography .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Arrangement ............................................................................................................................................