A Journal of the Lake Superior Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michigan Technological University Archives' Postcard Collection MTU-196

Michigan Technological University Archives' Postcard Collection MTU-196 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on February 08, 2019. Description is in English Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections 1400 Townsend Drive Houghton 49931 [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.mtu.edu/mtuarchives/ Michigan Technological University Archives' Postcard Collection MTU-196 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biography ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Collection Scope and Content Summary ....................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 4 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 5 A ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 B .................................................................................................................................................................. -

100 Years of Michigan State Parks

1 ourmidland.com 2 Page 2 | Week of May 6 -11, 2019 Which state park was Michigan’s first? As the DNR celebrates the 100th anniversary of Michigan state parks system, a natural question arises – what was Michigan’s first state park? Well, the answer depends on how you interpret the question and isn’t simple. The 2019 state parks centennial celebration is centered around the formation of the Michigan State Park Commission by the state Legislature on May 12, 1919. The commission was given responsibility for overseeing, acquiring and maintaining public lands and establishing Michigan’s state parks system. One of the state’s earliest purchases was the site of Interlochen State Park in 1917. Although the land was purchased prior to 1919, Interlochen was the first public park to be transferred to the Michigan State Park Commission in 1920 and is considered Michigan’s first state park. However, many consider Mackinac Island as Michigan’s first state park, which is also true. Approximately 25 years before legislation estab- lished the state park commission, the federal government gifted the Mackinac Island property it owned to the state in 1895. The island was designat- ed as Michigan’s first state park under the Mackinac State Park Commission. Because Mackinac Island is operated under the Mackinac State Park Commission and was not placed under the Michigan State Park Commission, there is more than one answer to the “first state park” question. Interlochen State Park The Michigan Legislature paid $60,000 for the land that became Interlochen State Park, located southwest of Traverse City, in 1917. -

(Icss) for Children by Pihp/Cmhsp

ICSS FOR CHILDREN BY PIHP/CMHSP PHIP CMHSP Contact phone number Region 1: NorthCare Network Copper Country Mental Health Services 906-482-9404 (serving Baraga, Houghton, Keweenaw and Ontonagon) Gogebic County CMH Authority 906-229-6120 or 800-348-0032 Hiawatha Behavioral Health 800-839-9443 (serving Chippewa, Schoolcraft and Mackinac counties) Pathways Community Mental Health 888-728-4929 (serving Delta, Alger, Luce and Marquette counties) Northpointe Behavioral Health 800-750-0522 Region 2: Northern Michigan Regional Entity Northern Lakes Community Mental Health 833-295-0616 Authority (serving Crawford, Grand Traverse, Leelanau, Missaukee, Roscommon and Wexford counties) Au Sable Valley CMH services (serving Oscoda, 844-225-8131 Ogemaw, Iosco counties) Centra Wellness Network (Manistee Benzie 877-398-2013 CMH) North Country CMH (serving Antrium, 800-442-7315 Charlevoix, Cheboygan, Emmett, Kalkaska and Otsego) 01/29/2019 ICSS FOR CHILDREN BY PIHP/CMHSP Northeast Michigan CMH (serving Alcona, (989) 356-2161 Alpena, Montmorency and Presque Isle (800) 968-1964 counties) (800) 442-7315 during non-business hours Region 3: Lakeshore Regional Entity Allegan County CMH services 269-673-0202 or 888-354-0596 CMH of Ottawa County 866-512-4357 Network 180 616-333-1000 (serving Kent County) HealthWest During business hours: 231-720-3200 (serving Muskegon County) Non-business hours: 231-722-HELP West Michigan CMH 800-992-2061 (serving Oceana, Mason and Lake counties) Oceana: 231-873-2108 Mason: 231-845-6294 Lake: 231-745-4659 Region 4: Southwest Michigan Behavioral Health Barry County Mental Health Authority 269-948-8041 Berrien County Community Mental Health 269-445-2451 Authority 01/29/2019 ICSS FOR CHILDREN BY PIHP/CMHSP Branch County Mental Health Authority (aka 888-725-7534 Pines Behavioral Health) Cass County CMH Authority (aka Woodlands) 800-323-0335 Kalamazoo Community Mental Health and 269-373-6000 or 888-373-6200 Substance Abuse Services CMH of St. -

Michigan Medicaid Applied Behavior Analysis Services Provider Directory

Medicaid Applied Behavior Analysis Services Provider Directory October 2019 www.michigan.gov/autism Regional Prepaid Inpatient Health Plans Region 1: NorthCare Network ....................................................................................................................... 3 Region 2: Northern Michigan Regional Entity .............................................................................................. 5 Region 3: Lakeshore Regional Entity ............................................................................................................. 7 Region 4: Southwest Michigan Behavioral Health ...................................................................................... 10 Region 5: Mid-State Health Network .......................................................................................................... 12 Region 6: Community Mental Health Partnership of Southeast Michigan................................................. 17 Region 7: Detroit-Wayne Mental Health Authority .................................................................................... 20 Region 8: Oakland Community Health Network ......................................................................................... 22 Region 9: Macomb County Community Mental Health .............................................................................. 24 Region 10 Prepaid Inpatient Health Plan .................................................................................................... 25 Region 1: NorthCare Network 200 W. -

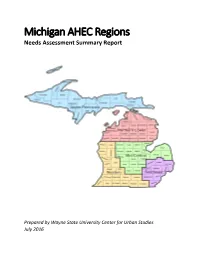

Michigan AHEC Regions Needs Assessment Summary Report

Michigan AHEC Regions Needs Assessment Summary Report Prepared by Wayne State University Center for Urban Studies July 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Southeast Michigan Region 1 AHEC Needs Assessment Mid‐Central Michigan Region 26 AHEC Needs Assessment Northern Lower Michigan Region 44 AHEC Needs Assessment Upper Peninsula Michigan Region 61 AHEC Needs Assessment Western Michigan Region 75 AHEC Needs Assessment Appendix 98 AHEC Needs Assessment Southeast Michigan Region Medically Underserved Summary Table 2 Medically Underserved Areas and Populations 3 Healthcare Professional Shortage Areas 4 Primary Care Physicians 7 All Clinically‐Active Primary Care Providers 8 Licensed Nurses 10 Federally Qualified Health Centers 11 High Schools 16 Health Needs 25 1 Medically Underserved Population Southeast Michigan AHEC Region Age Distribution Racial/Ethnic Composition Poverty Persons 65 Years of American Indian or Persons Living Below Children Living Below Persons Living Below Age and Older (%) Black (%) Alaska Native (%) Asian (%) Hispanic (%) Poverty (%) Poverty (%) 200% Poverty (%) Michigan 14.53 15.30 1.40 3.20 4.60 16.90 23.70 34.54 Genesee 14.94 22.20 1.50 1.40 3.10 21.20 32.10 40.88 Lapeer 14.68 1.50 1.00 0.60 4.30 11.60 17.20 30.48 Livingston 13.11 0.80 1.00 1.00 2.10 6.00 7.30 17.53 Macomb 14.66 10.80 1.00 3.90 2.40 12.80 18.80 28.72 Monroe 14.64 2.90 0.90 0.80 3.20 11.80 17.50 28.99 Oakland 13.90 15.10 1.00 6.80 3.60 10.40 13.80 22.62 St. -

2019 ANNUAL REPORT the Mackinac Island State Park Commission Was Created by the Michigan Legislature on May 31, 1895

2019 ANNUAL REPORT The Mackinac Island State Park Commission was created by the Michigan legislature on May 31, 1895. The commission’s purpose was to administer Michigan’s first state park, which had previously been Mackinac National Park, the United States’ second national park, from 1875 to 1895. The commission’s jurisdiction was extended in 1909 to Michilimackinac State Park in Mackinaw City, Michigan’s second state park. Over 80 percent of Mackinac Island is now included within the boundaries of Mackinac Island State Park, which also contains Fort Mackinac historic site. Colonial Michilimackinac and Old Mackinac Point Lighthouse are located within Michilimackinac State Park. In 1983 the commission also opened Historic Mill Creek Creek State Park, east of Mackinaw City. The historic sites and parks are together known as Mackinac State Historic Parks. Annual visitation to all these parks and museums is nearly 1,000,000. Mackinac State Historic Parks has been accredited by the American Alliance of Museums since 1972. Mackinac Island State Park Commission 2019 Annual Report Daniel J. Loepp Richard A. Manoogian William K. Marvin Chairman Vice Chairman Secretary Birmingham Taylor Mackinaw City Rachel Bendit Marlee Brown Phillip Pierce Richard E. Posthumus Ann Arbor Mackinac Island Grosse Pte. Shores Alto Mackinac State Historic Parks Staff Phil Porter, Director Executive Staff: Brian S. Jaeschke, Registrar Steven C. Brisson, Deputy Director Keeney A. Swearer, Exhibit Designer Nancy A. Stempky, Chief of Finance Craig P. Wilson, Curator of History Myron Johnson, Mackinac Island Park Manager Park Operations: Robert L. Strittmatter, Mackinaw City Park Manager Troy A. Allaire, Park & Rec. -

University of Michigan Regents, 1837-2009

FORMER MEMBERS OF UNIVERSITY GOVERNING BOARDS REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, 1837-20091 Thomas Fitzgerald ................ 1837-1900 Henry Whiting ................... 1858-1863 Robert McClelland ................ 1837-1900 Oliver L. Spaulding ............... 1858-1863 Michael Hoffman ................. 1837-1838 Luke Parsons .................... 1858-1862 John F. Porter .................... 1837-1838 Edward C. Walker ................ 1864-1881 Lucius Lyon ..................... 1837-1839 George Willard ................... 1864-1873 John Norvell..................... 1837-1839 Thomas D. Gilbert ................ 1864-1875 Seba Murphy .................... 1837-1839 Thomas J. Joslin .................. 1864-1867 John J. Adam .................... 1837-1840 Henry C. Knight .................. 1864-1867 Samuel Denton .................. 1837-1840 Alvah Sweetzer .................. 1864-1900 Gideon O. Whittemore ............. 1837-1840 James A. Sweezey................. 1864-1871 Henry Schoolcraft ................. 1837-1841 Cyrus M. Stockwell ................ 1865-1871 Isaac E. Crary .................... 1837-1843 J. M. B. Sill ...................... 1867-1869 Ross Wilkins .................... 1837-1842 Hiram A. Burt.................... 1868-1875 Zina Pitcher ..................... 1837-1852 Joseph Estabrook ................. 1870-1877 Gurdon C. Leech ................. 1838-1840 Jonas H. McGowan................ 1870-1877 Jonathan Kearsley................. 1838-1852 Claudius B. Grant ................. 1872-1879 Joseph W. Brown ................ -

OPENING of the Copper Country Intermediate School District Board

CCISD MINUTES –3/20/18 OPENING OF The Copper Country Intermediate School District Board of MEETING Education held its regular monthly meeting on Tuesday, March 20, 3/20/18 2018, at the Intermediate Service Center, 809 Hecla Street, Hancock, Michigan, beginning at 5:32 p.m. The meeting opened with the reciting of the “Pledge of Allegiance.” ROLL CALL MEMBERS PRESENT: Robert C. Tuomi, presiding; Nels S. Christopherson; Karen M. Johnson; Gale W. Eilola; Robert E. Loukus; and Lisa A. Tarvainen. MEMBER ABSENT: Robert L. Roy. ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF MEMBERS PRESENT: Katrina Carlson, Shawn Oppliger, Kristina Penfold, Mike Richardson and George Stockero. OTHER STAFF PRESENT: Jason Auel, Business Manager. GUEST PRESENT: Katrice Perkins, Reporter, Daily Mining Gazette. AGENDA & It was recommended by Superintendent George Stockero that the ADDENDUM submitted agenda, with addendum, be adopted as presented. It was moved by Mr. Loukus and seconded by Mrs. Tarvainen to adopt the agenda, with addendum, as presented. All yeas; motion carried. APPROVE It was recommended by Superintendent George Stockero that the MINUTES submitted minutes of the regular meeting of February 20, 2018, be 2/20/18 approved as presented. It was moved by Mrs. Johnson and seconded by Mr. Eilola to approve the minutes of the regular monthly meeting of February 20, 2018, as presented. All yeas; motion carried. APPROVE It was recommended by Business Manager Jason Auel and FINANCIAL Superintendent George Stockero that the financial statements be STATEMENTS accepted as presented. It was moved by Mr. Loukus and seconded by Mrs. Johnson to accept the financial statements as presented. All yeas; motion carried. -

Famous People from Michigan

APPENDIX E Famo[ People fom Michigan any nationally or internationally known people were born or have made Mtheir home in Michigan. BUSINESS AND PHILANTHROPY William Agee John F. Dodge Henry Joy John Jacob Astor Herbert H. Dow John Harvey Kellogg Anna Sutherland Bissell Max DuPre Will K. Kellogg Michael Blumenthal William C. Durant Charles Kettering William E. Boeing Georgia Emery Sebastian S. Kresge Walter Briggs John Fetzer Madeline LaFramboise David Dunbar Buick Frederic Fisher Henry M. Leland William Austin Burt Max Fisher Elijah McCoy Roy Chapin David Gerber Charles S. Mott Louis Chevrolet Edsel Ford Charles Nash Walter P. Chrysler Henry Ford Ransom E. Olds James Couzens Henry Ford II Charles W. Post Keith Crain Barry Gordy Alfred P. Sloan Henry Crapo Charles H. Hackley Peter Stroh William Crapo Joseph L. Hudson Alfred Taubman Mary Cunningham George M. Humphrey William E. Upjohn Harlow H. Curtice Lee Iacocca Jay Van Andel John DeLorean Mike Illitch Charles E. Wilson Richard DeVos Rick Inatome John Ziegler Horace E. Dodge Robert Ingersol ARTS AND LETTERS Mitch Albom Milton Brooks Marguerite Lofft DeAngeli Harriette Simpson Arnow Ken Burns Meindert DeJong W. H. Auden Semyon Bychkov John Dewey Liberty Hyde Bailey Alexander Calder Antal Dorati Ray Stannard Baker Will Carleton Alden Dow (pen: David Grayson) Jim Cash Sexton Ehrling L. Frank Baum (Charles) Bruce Catton Richard Ellmann Harry Bertoia Elizabeth Margaret Jack Epps, Jr. William Bolcom Chandler Edna Ferber Carrie Jacobs Bond Manny Crisostomo Phillip Fike Lilian Jackson Braun James Oliver Curwood 398 MICHIGAN IN BRIEF APPENDIX E: FAMOUS PEOPLE FROM MICHIGAN Marshall Fredericks Hugie Lee-Smith Carl M. -

Michigan's Copper Country" Lets You Experience the Require the Efforts of Many People with Different Excitement of the Discovery and Development of the Backgrounds

Michigan’s Copper Country Ellis W. Courter Contribution to Michigan Geology 92 01 Table of Contents Preface .................................................................................................................. 2 The Keweenaw Peninsula ........................................................................................... 3 The Primitive Miners ................................................................................................. 6 Europeans Come to the Copper Country ....................................................................... 12 The Legend of the Ontonagon Copper Boulder ............................................................... 18 The Copper Rush .................................................................................................... 22 The Pioneer Mining Companies................................................................................... 33 The Portage Lake District ......................................................................................... 44 Civil War Times ...................................................................................................... 51 The Beginning of the Calumet and Hecla ...................................................................... 59 Along the Way to Maturity......................................................................................... 68 Down the South Range ............................................................................................. 80 West of the Ontonagon............................................................................................ -

Separately Elevates and Broadens Our Masonic Experience

There Is So Much More Message from Robert O. Ralston, 33o Sovereign Grand Commander, A.A.S.R., N.M.J. One of the many exciting insights that is revolutionizing American business is something called teaming. Automobile designers, manufacturing experts, marketers, advertising specialists, engineers, and others at Ford locations across the world worked together to create the new Ford Taurus car. The end result is a far better product brought to the market in loss time and at lower cost. The total resources of the Ford Motor Company were involved in creating the new car. And it all happened because of teaming. The lesson of teaming applies to Freemasonry. Each Masonic body has a unique perspective on our Fraternity, as well as specialized resources and members with unusual expertise. Each Masonic organization is an incredibly important and valuable resource for all of Freemasonry. Each Masonic body contributes to the rich texture of the Fraternity, builds member allegiance, serves noble charitable purposes, and extends the reach of Freemasonry. But even with the many wonderful accomplishments of the individual organizations, we cannot fulfill our Masonic mission alone. Each group is a facet on the Masonic jewel. Each Masonic body makes a contribution that enhances the lives of the others. We are enriched by each other. Most importantly, we are all Masons. The Symbolic Lodge binds us together, and it is this common Masonic experience that makes it possible for us to be Knight Templar Masons, Scottish Rite Masons, and Shrine Masons. What we do separately elevates and broadens our Masonic experience. The Internet is making it possible for tens of millions of people around the world to talk to each other at home and at work. -

Mackinac Island & Lake Huron

Mackinac Island & Lake Huron from The Grand Hotel - Elks & Islands 9 Nights / 10 Days Day 1 - Arrive to Michigan (famous for its red pants), get ready to discover wonderful historic rides. Ford Rouge Factory Tour: Pop open the hood on game-changing Depart for Dearborn, MI. Enjoy a dinner buffet included at an eatery with technology, sustainable design and sheer American grit at America’s the vibe of being in a 1920’s service station/prohibition bar with old style greatest manufacturing experience. Get an inside look at the making of brick, dark colors, rich wood and hand-hammered copper bar top, with America’s most iconic truck, the Ford F-150, and immerse yourself in many other unique features. After dinner, check-in to your hotel. (Meals: modern manufacturing’s most progressive concepts. Experience the D) awe-inspiring scale of a real factory floor as you rev up your inner Day 2 - Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, & Ford engineer. This is where big ideas gain momentum. Enjoy lunch on own Rouge Factory Tour while visiting museum. Return to hotel for rest prior to an included dinner Enjoy breakfast at the hotel. Meet in the hotel lobby and depart. Arrive at a vibrant steakhouse offering Italian favorites such as homemade pasta with your All-Access Tickets at Henry Ford Museum and Tour, Greenfield plus a curated wine list. (Meals: B, D) Village and Ride, Ford Rouge Factory Tour, and Giant Screen Experience. Day 3 - Henry Ford Museum and Tour & Mansion Guided Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation: Step into a world where Behind the Scenes Tour past innovations fuel the imagination of generations to come.