Table of Contents Item Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern Eine Beschäftigung I

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern eine Beschäftigung i. S. d. ZRBG schon vor dem angegebenen Eröffnungszeitpunkt glaubhaft gemacht ist, kann für die folgenden Gebiete auf den Beginn der Ghettoisierung nach Verordnungslage abgestellt werden: - Generalgouvernement (ohne Galizien): 01.01.1940 - Galizien: 06.09.1941 - Bialystok: 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ostland (Weißrussland/Weißruthenien): 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ukraine (Wolhynien/Shitomir): 05.09.1941 Eine Vorlage an die Untergruppe ZRBG ist in diesen Fällen nicht erforderlich. Datum der Nr. Ort: Gebiet: Eröffnung: Liquidierung: Deportationen: Bemerkungen: Quelle: Ergänzung Abaujszanto, 5613 Ungarn, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, Braham: Abaújszántó [Hun] 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Kassa, Auschwitz 27.04.2010 (5010) Operationszone I Enciklopédiája (Szántó) Reichskommissariat Aboltsy [Bel] Ostland (1941-1944), (Oboltsy [Rus], 5614 Generalbezirk 14.08.1941 04.06.1942 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, 2001 24.03.2009 Oboltzi [Yid], Weißruthenien, heute Obolce [Pol]) Gebiet Vitebsk Abony [Hun] (Abon, Ungarn, 5443 Nagyabony, 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 2001 11.11.2009 Operationszone IV Szolnokabony) Ungarn, Szeged, 3500 Ada 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Braham: Enciklopédiája 09.11.2009 Operationszone IV Auschwitz Generalgouvernement, 3501 Adamow Distrikt Lublin (1939- 01.01.1940 20.12.1942 Kossoy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 09.11.2009 1944) Reichskommissariat Aizpute 3502 Ostland (1941-1944), 02.08.1941 27.10.1941 USHMM 02.2008 09.11.2009 (Hosenpoth) Generalbezirk -

Table of Contents Item Transcript

DIGITAL COLLECTIONS ITEM TRANSCRIPT Gregory Fein. Full, unedited interview, 2009 ID LA008.interview PERMALINK http://n2t.net/ark:/86084/b41h6r ITEM TYPE VIDEO ORIGINAL LANGUAGE RUSSIAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM TRANSCRIPT ENGLISH TRANSLATION 2 CITATION & RIGHTS 13 2021 © BLAVATNIK ARCHIVE FOUNDATION PG 1/13 BLAVATNIKARCHIVE.ORG DIGITAL COLLECTIONS ITEM TRANSCRIPT Gregory Fein. Full, unedited interview, 2009 ID LA008.interview PERMALINK http://n2t.net/ark:/86084/b41h6r ITEM TYPE VIDEO ORIGINAL LANGUAGE RUSSIAN TRANSCRIPT ENGLISH TRANSLATION —Today is March 17, 2009. We are in Los Angeles, meeting a veteran of the Great Patriotic War. Please introduce yourself and tell us about your life before the war. What was your family like, what did your parents do, what sort of school did you attend? How did the war begin for you and what did you do during the war? My name is Gregory Fein and I was born on April 18, 1921, in Propolsk [Prapoisk], which was later renamed Slavgorod [Slawharad], Mahilyow Region, Belarus. My father was an artisan bootmaker. We lived Propolsk until 1929. That year my family moved to Krasnapolle, a nearby town in the same region. We moved because my father had to work in an artel. In order for his children to have an education, he had to join an artisan cooperative rather than work alone. His skills were in demand in Kransopole [Krasnapolle], so we moved there, because there was a cooperative there. There were five children in the family and I was the youngest. My eldest sister Raya worked as a labor and delivery nurse her entire life. -

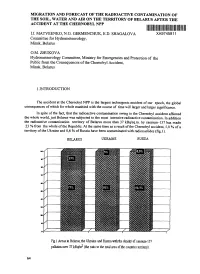

Migration and Forecast of the Radioactive Contamination of the Soil, Water and Air on the Territory of Belarus After the Accident at the Chernobyl Npp

MIGRATION AND FORECAST OF THE RADIOACTIVE CONTAMINATION OF THE SOIL, WATER AND AIR ON THE TERRITORY OF BELARUS AFTER THE ACCIDENT AT THE CHERNOBYL NPP I.I. MATVEENKO, N.G. GERMENCHUK, E.D. SHAGALOVA XA9745811 Committee for Hydrometeorology, Minsk, Belarus O.M. ZHUKOVA Hydrometeorology Committee, Ministry for Emergencies and Protection of the Public from the Consequences of the Chernobyl Accident, Minsk, Belarus 1.INTRODUCTION The accident at the Chernobyl NPP is the largest technogenic accident of our epoch, the global consequences of which for whole manhind with the course of time will larger and larger significance. In spite of the fact, that the radioactive contamination owing to the Chernobyl accident affected the whole world, just Belarus was subjected to the most intensive radioactive contamination. In addition the radioactive contamination territory of Belarus more than 37 kBq/sq.m. by caesium-137 has made 23 % from the whole of the Republic. At the same time as a result of the Chernobyl accident, 5,0 % of a territory of the Ukraine and 0,6 % of Russia have been contaminated with radionuclides (fig.l). BELARUS UKRAINE RUSSIA Fig. 1 Areas in Belarus, the Ukraine and Russia with the density of caesium-137 pollution over 37 kBq/a^ (tile ratio to the total area of the countries territory). 64 By virtue of a primary direction of movement of air masses, contamination with radionuclides in the northern-western, northern and northern-eastern directions in the initial period after the accident, the significant increase of the exposition doze rate was registered practically on the whole territory of Belarus. -

FEEFHS Journal Volume II 1994

FEEFHS Newsletter of the Federation of East European Family History Societies Val 2,No. 3 July 1994 ISSN 1077-1247, PERSI #EEFN A total of about 75 people registered for the convention, and many others assisted in various capacities. There were a few unexpected problems, of course, but altogether the meetings THE FIRST FEEFHS CONVENTION, provided a valuable service, enough so tbat at the end of MAYby John 14-16, C. Alleman 1994 convention it was tentatively decided that next year we will try to hold two conventions, in Calgary, Alberta, and Cleveland, Our first FEEFHS convention was successfully held as Ohio, in order to help serve the interests of people who have scheduled on May 14-16, 1994, at the Howard Johnson Hotel difficulty coming to Satt Lake City. in Saft Lake City. The program followed the plan published in our last issue of the Newsletter, for the most part, and we will not repeat it here in order to save space. Anyone who desires more information on the suhjects presented in the conference addresses is encouraged to write directly to the speakers at the addresses given there. THANK YOU, CONVENTION by Ed Brandt,SPEAKERS Program Chair The most importanl business of the convention was the installation of permanent officers. Charles M. Hall, Edward Many people attending the FEEFHS convention commented R. Brandt, and John D. Movius had been elected and were favorably on the quality of our convention speakers and their installed as president, Ist vice president, and 2nd vice presentations. I have heard from quite a few who could not president, respectively. -

World Bank Documents

The World Bank Report No: ISR13051 Implementation Status & Results Belarus Water Supply and Sanitation Project (P101190) Operation Name: Water Supply and Sanitation Project (P101190) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 11 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 28-Dec-2013 Country: Belarus Approval FY: 2009 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: EUROPE AND CENTRAL ASIA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Board Approval Date 30-Sep-2008 Original Closing Date 30-Jun-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date Last Archived ISR Date 25-Jun-2013 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 17-Feb-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2014 Actual Mid Term Review Date 16-May-2011 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) To increase access to water supply services and to improve the quality of water supply and wastewater services in selected urban areas in six participating oblasts of the Borrower. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? ● Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Rehabilitation of water supply and sanitation systems 53.60 Support to the preparation and sustainability of investments 6.05 Project implementation and management 0.20 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Public Disclosure Authorized Overall Risk Rating Moderate Substantial Implementation Status Overview Overall progress is moderately satisfactory: disbursements have started to pick up over the last six months and are now increasing at sustained full speed. Construction activities are now back to full speed in all sub-projects under implementation. -

Festuca Arietina Klok

ACTA BIOLOGICA CRACOVIENSIA Series Botanica 59/1: 35–53, 2017 DOI: 10.1515/abcsb-2017-0004 MORPHOLOGICAL, KARYOLOGICAL AND MOLECULAR CHARACTERISTICS OF FESTUCA ARIETINA KLOK. – A NEGLECTED PSAMMOPHILOUS SPECIES OF THE FESTUCA VALESIACA AGG. FROM EASTERN EUROPE IRYNA BEDNARSKA1*, IGOR KOSTIKOV2, ANDRII TARIEIEV3 AND VACLOVAS STUKONIS4 1Institute of Ecology of the Carpathians, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 4 Kozelnytska str., Lviv, 79026, Ukraine 2Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, 64 Volodymyrs’ka str., Kyiv, 01601, Ukraine 3Ukrainian Botanical Society, 2 Tereshchenkivska str., Kyiv, 01601, Ukraine 4Lithuanian Institute of Agriculture, LT-58343 Akademija, Kedainiai distr., Lithuania Received February 20, 2015; revision accepted March 20, 2017 Until recently, Festuca arietina was practically an unknown species in the flora of Eastern Europe. Such a situa- tion can be treated as a consequence of insufficient studying of Festuca valesiaca group species in Eastern Europe and misinterpretation of the volume of some taxa. As a result of a complex study of F. arietina populations from the territory of Ukraine (including the material from locus classicus), Belarus and Lithuania, original anatomy, morphology and molecular data were obtained. These data confirmed the taxonomical status of F. arietina as a separate species. Eleven morphological and 12 anatomical characters, ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 cluster of nuclear ribo- somalKeywords: genes, as well as the models of secondary structure of ITS1 and ITS2 transcripts were studied in this approach. It was found for the first time that F. arietina is hexaploid (6x = 42), which is distinguished from all the other narrow-leaved fescues by specific leaf anatomy as well as in ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 sequences. -

Strategic Leadership. Implementation of the Healthy City Project in Horki, Belarus Andrei Famenka,1 Sviatlana Bezzubenka,2 Natalya Karobkina,2 Raisa Prudnikova3

347 SHORT COMMUNICATION Cross-sectoral health processes: strategic leadership. implementation of the healthy city project in Horki, Belarus Andrei Famenka,1 Sviatlana Bezzubenka,2 Natalya Karobkina,2 Raisa Prudnikova3 1 WHO Country Office, Minsk, Belarus 2 Horki Central District Hospital, Horki, Mogilev Region, Belarus 3 Horki District Centre for Hygiene and Epidemiology, Horki, Mogilev Region, Belarus Corresponding author: Andrei Famenka (email: [email protected]) ABSTRACT This article describes the implementation of the Healthy City project in combat noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and promote a healthy lifestyle1 the small town of Horki, Belarus. Particular attention is paid to the role were adapted to local conditions and more flexible strategies were adopted of strategic leadership in cross-sectoral health collaboration. Factors to implement the main areas of these programmes. The experience gained contributing to the successful implementation of the project included the so far from the Horki – Healthy City project shows that the leadership of local interest of the local authorities, technical and advisory support from the governments has facilitated the harmonious and coordinated work of various WHO European Healthy Cities Network, and the financial independence of the sectors in accordance with WHO’s research-based recommendations for local authorities. A special feature of the Horki – Healthy City project is that improving public health and achieving health equity at the local level. the goals and objectives of the nationwide cross-sectoral -

History Teaching in Belarus: Between Europe and Russia Anna Zadora, University of Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France

History Teaching In Belarus: Between Europe And Russia Anna Zadora, University of Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research [IJHLTR], Volume 15, Number 1 – Autumn/Winter 2017 Historical Association of Great Britain www.history.org.uk ISSN: 14472-9474 Abstract: This paper is devoted to social uses of history teaching and history textbooks. It analyses, first, how the history of the lands of Belarus, at the crossroads between Europe and Eurasia, was not recognized during the Soviet Era. No one school textbook on history of Belarus existed. Belarus declared its independence in the 1991. Next, it analyses how, during Perestroika (from 1985) and in the early 1990s, a new history curriculum was introduced which emphasize fundamental changes in the teaching of history, in its content, methodology, structure and pedagogy, encompassing principles of humanism, democracy and the rejection of dogma and stereotypes. History teaching should legitimate the new state: independent from Soviet past and Russian influence and European-orientated state. Historians were invited to write new textbooks, which encouraged critical thinking, reflection, multiple perspectives and European roots in Belarusian history. Finally it studies how the current government of Belarus aspires to return to a dogmatic, Soviet, Russian-orientated version of Belarusian history which does not foster a sense of belonging to a national community or justify the place of Belarus in Europe or the global system. The paper focuses on school textbooks, which are very sensitive and precise indicators of the social uses of history and history teaching. Keywords: Belarus, Europe History, Historiography, Education, Identity, Russia, Soviet [USSR] and post Soviet period INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HISTORICAL LEARNING, TEACHING AND RESEARCH Vol. -

Green Economy and Agribusiness

Green economy and agribusiness. New agrarian transformation in Belarus pt er c x E Przejdź do produktu na www.ksiegarnia.beck.pl Chapter 1 The theoretical and methodological background of sustainable agribusiness development based on the principles of ” green economy” 1.1. The concept of ” green economy” as an effective tool for sustainable development The National Plan of Actions for the Development of ” green economy” in the Republic of Belarus until 2020 was developed in accordance with the Program of social and economic development of the Republic of Belarus for the years 2016–2020, approved by the Decree of the President of the Republic of Belarus dated December 15, 2016, no. 466 [230]. For the purposes of this National Plan, the following key terms and their definitions are used: ” green” economy – a model of economic organization aimed at achieving the goals of social and economic development with a significant reduction in environmental risks and rates of environmental degradation; ” green” procurement – a procurement system (process), in which the needs for goods, works, services are considered taking into account the ratio of price and quality throughout their life cycle and the impact on the environment; production of organic products – the work on the direct manufacturing, processing of organic products by using methods, techniques, technologies stipulated by the regulatory legal acts, including the technical National legislative Internet portal of the Re- public of Belarus, 12.28.2016, 5/43102 2 regulatory legal acts, and -

The Journal of the San Francisco Bay Area Jewish Genealogical Society Sephardic Ancestry in Belarus

The Journal of the San Francisco Bay Area Jewish Genealogical Society Volume XXXVIII, Number 1/2 February/May 2018 Sephardic Ancestry in Belarus Kevin Alan Brook continues his research into the Sephardic presence in eastern Europe with a visit to Belarus. See page 5. Also in This Issue Autosomal DNA Transfers: Which Companies Accept Which Tests? Roberta Estes ......................................................... 7 Jewish Censuses and Substitutes Ted Bainbridge, Ph.D. ......................................... 10 Genealogy: The Changes 25 Years Have Brought Jeff Lewy ............................................................... 11 So You Want to Come to the 2018 IAJGS Warsaw Conference? Great! Now What? Robinn Magid ...................................................... 13 SFBAJGS Activity Report for 2017 Jeff Lewy ............................................................... 18 Departments Semion Lvovich Abugov, portrait (see page 5) President’s Message .............................................. 2 Society News ......................................................... 3 Genealogy Calendar ............................................. 4 Family Finder Update ........................................ 12 Upcoming SFBAJGS Events ............... back cover ZichronNote: Journal of the San Francisco Bay Area Jewish Genealogical Society ZichronNote President’s Message Journal of the San Francisco Bay Area Jewish Genealogy in Poland Jewish Genealogical Society Jeremy Frankel, SFBAJGS President © 2018 San Francisco Bay Area Jewish Genealogical -

Belarus Still Retains Death Penalty

REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 2002 2 REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 2002 PREFACE: GENERALIZATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS 2002 brought about no changes for the better in the overall situation with human rights in Belarus. In spite of certain traits witnessing the regime liberalization the official politics was still accompanied with violations of international standards in the branches of human rights and the national legislation. The situation with freedom of conscience and liberty of speech has become considerably worse. Still violated are the civil rights to peaceful assemblies, participation in unions and associations, exists criminal persecution for political reasons, the problem of the missing Belarusian politicians and public activists remains unsolved. Absence of just, objective, independent and objective court impedes defense of the violated rights… For the Belarusian State human rights still aren’t the irreversible principle that should dominate in all manifestations of the State policy. The highest level authorities are constantly speaking of human rights violations as an informational campaign of certain politicians aimed at pressurization of the government. The attention of international organizations to human rights violations in Belarus is almost always treated as an attempt of interference with internal affairs of Belarus. The interest of AMG OSCE to human rights issues resulted in extrusion of OSCE Belarusian mission. The authorities refused to prolong visas to members of AMG OSCE, violating the earlier diplomatic agreements. The Belarusian authorities try to conceal the internal human rights issues from international observers. Conflict with OSCE is not the only example. The international experts who wanted to take part in the conference International Standards of Democratic Election and Belarusian legislation, organized by Human Rights Center Viasna in December 2002 were denied access to Belarus. -

C., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, Telephone 978-750-8400, Fax 978-750-4470

Report No: ACS13961 . Republic of Belarus Public Disclosure Authorized Regional Development Policy Notes The Spatial Dimension of Structural Change . June 22, 2015 Public Disclosure Authorized . GMFDR EUROPE AND CENTRAL ASIA . Public Disclosure Authorized . Document of the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Standard Disclaimer: This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Copyright Statement: The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202- 522-2422, e-mail [email protected].