Table of Contents Item Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern Eine Beschäftigung I

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern eine Beschäftigung i. S. d. ZRBG schon vor dem angegebenen Eröffnungszeitpunkt glaubhaft gemacht ist, kann für die folgenden Gebiete auf den Beginn der Ghettoisierung nach Verordnungslage abgestellt werden: - Generalgouvernement (ohne Galizien): 01.01.1940 - Galizien: 06.09.1941 - Bialystok: 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ostland (Weißrussland/Weißruthenien): 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ukraine (Wolhynien/Shitomir): 05.09.1941 Eine Vorlage an die Untergruppe ZRBG ist in diesen Fällen nicht erforderlich. Datum der Nr. Ort: Gebiet: Eröffnung: Liquidierung: Deportationen: Bemerkungen: Quelle: Ergänzung Abaujszanto, 5613 Ungarn, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, Braham: Abaújszántó [Hun] 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Kassa, Auschwitz 27.04.2010 (5010) Operationszone I Enciklopédiája (Szántó) Reichskommissariat Aboltsy [Bel] Ostland (1941-1944), (Oboltsy [Rus], 5614 Generalbezirk 14.08.1941 04.06.1942 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, 2001 24.03.2009 Oboltzi [Yid], Weißruthenien, heute Obolce [Pol]) Gebiet Vitebsk Abony [Hun] (Abon, Ungarn, 5443 Nagyabony, 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 2001 11.11.2009 Operationszone IV Szolnokabony) Ungarn, Szeged, 3500 Ada 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Braham: Enciklopédiája 09.11.2009 Operationszone IV Auschwitz Generalgouvernement, 3501 Adamow Distrikt Lublin (1939- 01.01.1940 20.12.1942 Kossoy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 09.11.2009 1944) Reichskommissariat Aizpute 3502 Ostland (1941-1944), 02.08.1941 27.10.1941 USHMM 02.2008 09.11.2009 (Hosenpoth) Generalbezirk -

Download Book

84 823 65 Special thanks to the Independent Institute of Socio-Economic and Political Studies for assistance in getting access to archival data. The author also expresses sincere thanks to the International Consortium "EuroBelarus" and the Belarusian Association of Journalists for information support in preparing this book. Photos by ByMedia.Net and from family albums. Aliaksandr Tamkovich Contemporary History in Faces / Aliaksandr Tamkovich. — 2014. — ... pages. The book contains political essays about people who are well known in Belarus and abroad and who had the most direct relevance to the contemporary history of Belarus over the last 15 to 20 years. The author not only recalls some biographical data but also analyses the role of each of them in the development of Belarus. And there is another very important point. The articles collected in this book were written at different times, so today some changes can be introduced to dates, facts and opinions but the author did not do this INTENTIONALLY. People are not less interested in what we thought yesterday than in what we think today. Information and Op-Ed Publication 84 823 © Aliaksandr Tamkovich, 2014 AUTHOR’S PROLOGUE Probably, it is already known to many of those who talked to the author "on tape" but I will reiterate this idea. I have two encyclopedias on my bookshelves. One was published before 1995 when many people were not in the position yet to take their place in the contemporary history of Belarus. The other one was made recently. The fi rst book was very modest and the second book was printed on classy coated paper and richly decorated with photos. -

National Threat Assessment 2021

DEFENCE INTELLIGENCE STATE SECURITY AND SECURITY DEPARTMENT OF SERVICE UNDER THE REPUBLIC OF THE MINISTRY OF LITHUANIA NATIONAL DEFENCE NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT 2021 DEFENCE INTELLIGENCE STATE SECURITY AND SECURITY DEPARTMENT OF SERVICE UNDER THE REPUBLIC OF THE MINISTRY OF LITHUANIA NATIONAL DEFENCE NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT 2021 VILNIUS, 2021 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 FOREWORD 5 SUMMARY 8 NEW SECURITY CHALLENGES 12 REGIONAL SECURITY 17 MILITARY SECURITY 27 ACTIVITIES OF HOSTILE INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY SERVICES 41 PROTECTION OF CONSTITUTIONAL ORDER 50 INFORMATION SECURITY 54 ECONOMIC AND ENERGY SECURITY 61 TERRORISM AND GLOBAL SECURITY 67 3 INTRODUCTION The National Threat Assessment by the State Security Department of the Republic of Lithuania (VSD) and the Defence Intelligence and Security Service under the Ministry of National Defence of the Republic of Lithuania (AOTD) is presented to the public in accordance with Articles 8 and 26 of the Law on Intelligence of the Republic of Lithuania. The document provides consolidated, unclassified assessment of threats and risks to national security of the Repub- lic of Lithuania prepared by both intelligence services. The document assesses events, processes and trends that correspond to the intelligence requirements approved by the State Defence Council. Based on them and considering the long-term trends affecting national security, the document provides the assessment of major challenges that the Lithuanian national security is to face in the near term (2021–2022). The assessments of long-term -

Table of Contents Item Transcript

DIGITAL COLLECTIONS ITEM TRANSCRIPT Gregory Fein. Full, unedited interview, 2009 ID LA008.interview PERMALINK http://n2t.net/ark:/86084/b41h6r ITEM TYPE VIDEO ORIGINAL LANGUAGE RUSSIAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM TRANSCRIPT ENGLISH TRANSLATION 2 CITATION & RIGHTS 13 2021 © BLAVATNIK ARCHIVE FOUNDATION PG 1/13 BLAVATNIKARCHIVE.ORG DIGITAL COLLECTIONS ITEM TRANSCRIPT Gregory Fein. Full, unedited interview, 2009 ID LA008.interview PERMALINK http://n2t.net/ark:/86084/b41h6r ITEM TYPE VIDEO ORIGINAL LANGUAGE RUSSIAN TRANSCRIPT ENGLISH TRANSLATION —Today is March 17, 2009. We are in Los Angeles, meeting a veteran of the Great Patriotic War. Please introduce yourself and tell us about your life before the war. What was your family like, what did your parents do, what sort of school did you attend? How did the war begin for you and what did you do during the war? My name is Gregory Fein and I was born on April 18, 1921, in Propolsk [Prapoisk], which was later renamed Slavgorod [Slawharad], Mahilyow Region, Belarus. My father was an artisan bootmaker. We lived Propolsk until 1929. That year my family moved to Krasnapolle, a nearby town in the same region. We moved because my father had to work in an artel. In order for his children to have an education, he had to join an artisan cooperative rather than work alone. His skills were in demand in Kransopole [Krasnapolle], so we moved there, because there was a cooperative there. There were five children in the family and I was the youngest. My eldest sister Raya worked as a labor and delivery nurse her entire life. -

Geographic Structure of Road Transportation and Logistics Infrastructure in the Republic of Belarus

ISSN 1426-5915 e-ISSN 2543-859X 20(2)/2017 Prace Komisji Geografii Komunikacji PTG 2017, 20(2), 8-18 DOI 10.4467/2543859XPKG.17.007.7389 GeoGraPhic sTrucTure of road TransPorTaTion and loGisTics infrasTrucTure in The rePublic of belarus Struktura geograficzna infrastruktury transportu drogowego i logistyki w Republice Białorusi andrei bezruchonak Department of Economic Geography of Foreign Countries, Faculty of Geography, Belarusian State University, Leningradskaya st. 16, 220030, Minsk, Belarus e-mail: [email protected] citation: Bezruchonak A., 2017, Geographic structure of road transportation and logistics infrastructure in the Republic of Belarus, Prace Komisji Geografii Komunikacji PTG, 20(2), 8-18. abstract: Transportation, representing 6% of GDP, plays vital role in social and economic development of the Republic of Belarus. The purpose of this article is to present the geographic analysis of current spatial structure of the road transportation in Belarus in 2000-2014. The choice of transport mode for the article was influenced by several factors, such as historic devel- opment, network coverage, transformational changes in productivity, rapid increase in car ownership numbers, emergence of logistic centers and intelligent transportation systems. The article reviews the range of topics, including morphology of the major roads network, logistic centers spatial distribution and regional features of passenger and cargo productivity, discusses current transformational changes within the road transportation sector in Belarus. The key findings indicate that current changes in spatial structure of the road transportation in Belarus have uneven nature, shaped by social, economic, political and geopolitical external and internal factors and are a subject of interest for both transportation researchers and practitioners. -

General Conclusions and Basic Tendencies 1. System of Human Rights Violations

REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 2003 2 REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 2003 INTRODUCTION: GENERAL CONCLUSIONS AND BASIC TENDENCIES 1. SYSTEM OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS The year 2003 was marked by deterioration of the human rights situation in Belarus. While the general human rights situation in the country did not improve, in its certain spheres it significantly changed for the worse. Disrespect for and regular violations of the basic constitutional civic rights became an unavoidable and permanent factor of the Belarusian reality. In 2003 the Belarusian authorities did not even hide their intention to maximally limit the freedom of speech, freedom of association, religious freedom, and human rights in general. These intentions of the ruling regime were declared publicly. It was a conscious and open choice of the state bodies constituting one of the strategic elements of their policy. This political process became most visible in formation and forced intrusion of state ideology upon the citizens. Even leaving aside the question of the ideology contents, the very existence of an ideology, compulsory for all citizens of the country, imposed through propaganda media and educational establishments, and fraught with punitive sanctions for any deviation from it, is a phenomenon, incompatible with the fundamental human right to have a personal opinion. Thus, the state policy of the ruling government aims to create ideological grounds for consistent undermining of civic freedoms in Belarus. The new ideology is introduced despite the Constitution of the Republic of Belarus which puts a direct ban on that. -

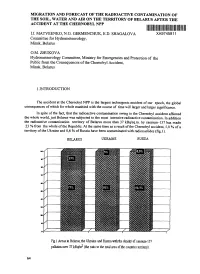

Migration and Forecast of the Radioactive Contamination of the Soil, Water and Air on the Territory of Belarus After the Accident at the Chernobyl Npp

MIGRATION AND FORECAST OF THE RADIOACTIVE CONTAMINATION OF THE SOIL, WATER AND AIR ON THE TERRITORY OF BELARUS AFTER THE ACCIDENT AT THE CHERNOBYL NPP I.I. MATVEENKO, N.G. GERMENCHUK, E.D. SHAGALOVA XA9745811 Committee for Hydrometeorology, Minsk, Belarus O.M. ZHUKOVA Hydrometeorology Committee, Ministry for Emergencies and Protection of the Public from the Consequences of the Chernobyl Accident, Minsk, Belarus 1.INTRODUCTION The accident at the Chernobyl NPP is the largest technogenic accident of our epoch, the global consequences of which for whole manhind with the course of time will larger and larger significance. In spite of the fact, that the radioactive contamination owing to the Chernobyl accident affected the whole world, just Belarus was subjected to the most intensive radioactive contamination. In addition the radioactive contamination territory of Belarus more than 37 kBq/sq.m. by caesium-137 has made 23 % from the whole of the Republic. At the same time as a result of the Chernobyl accident, 5,0 % of a territory of the Ukraine and 0,6 % of Russia have been contaminated with radionuclides (fig.l). BELARUS UKRAINE RUSSIA Fig. 1 Areas in Belarus, the Ukraine and Russia with the density of caesium-137 pollution over 37 kBq/a^ (tile ratio to the total area of the countries territory). 64 By virtue of a primary direction of movement of air masses, contamination with radionuclides in the northern-western, northern and northern-eastern directions in the initial period after the accident, the significant increase of the exposition doze rate was registered practically on the whole territory of Belarus. -

FEEFHS Journal Volume II 1994

FEEFHS Newsletter of the Federation of East European Family History Societies Val 2,No. 3 July 1994 ISSN 1077-1247, PERSI #EEFN A total of about 75 people registered for the convention, and many others assisted in various capacities. There were a few unexpected problems, of course, but altogether the meetings THE FIRST FEEFHS CONVENTION, provided a valuable service, enough so tbat at the end of MAYby John 14-16, C. Alleman 1994 convention it was tentatively decided that next year we will try to hold two conventions, in Calgary, Alberta, and Cleveland, Our first FEEFHS convention was successfully held as Ohio, in order to help serve the interests of people who have scheduled on May 14-16, 1994, at the Howard Johnson Hotel difficulty coming to Satt Lake City. in Saft Lake City. The program followed the plan published in our last issue of the Newsletter, for the most part, and we will not repeat it here in order to save space. Anyone who desires more information on the suhjects presented in the conference addresses is encouraged to write directly to the speakers at the addresses given there. THANK YOU, CONVENTION by Ed Brandt,SPEAKERS Program Chair The most importanl business of the convention was the installation of permanent officers. Charles M. Hall, Edward Many people attending the FEEFHS convention commented R. Brandt, and John D. Movius had been elected and were favorably on the quality of our convention speakers and their installed as president, Ist vice president, and 2nd vice presentations. I have heard from quite a few who could not president, respectively. -

Int Cat Css Blr 30785 E

The Cost of Speaking Out Overview of human rights abuses committed by Belarusian authorities during peaceful protests in February-March 2017 © Truth Hounds Truth Hounds E [email protected] /facebook.com/truthhounds/ W truth-hounds.org IPHR - International Partnership for Human Rights Square de l'Aviation 7A 1070 Brussels, Belgium E [email protected] @IPHR W IPHRonline.org /facebook.com/iphronline CSP - Civic Solidarity Platform W civicsolidarity.org @CivicSolidarity /facebook.com/SivicSolidarity Crimea SOS E [email protected] /facebook.com/KRYM.SOS/ W krymsos.com Table of contents 1. Introduction and methodology 4 2. Chronological overview of events 5 2.1. February protests against the law on taxing the unemployed 5 2.2. March wave of administrative arrests of civil society activists and journalists 6 2.3. Increasing use of force by law enforcement officials 7 2.4. Criminal and administrative arrests prior to the 25 March Freedom Day protest in Minsk 9 2.5 Ill-treatment, excessive use of force and arbitrary detentions by police on 25 March - Freedom Day in Minsk 10 2.6 Raid of NGO HRC Viasna office and detention of 57 human rights defenders 14 2.7. Further arrests and reprisals by the authorities 14 2.8. Criminal cases related to allegations of attempted armed violence 16 3. Police use of force and arbitrary detentions during assemblies 17 3.1. International standards 17 3.2. Domestic legislation 18 3.2. Structure of the law enforcement services 19 3.4. Patterns of human rights abuses 19 4. Overview of concerns related to violations of freedom of assembly 20 4.1. -

World Bank Documents

The World Bank Report No: ISR13051 Implementation Status & Results Belarus Water Supply and Sanitation Project (P101190) Operation Name: Water Supply and Sanitation Project (P101190) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 11 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 28-Dec-2013 Country: Belarus Approval FY: 2009 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: EUROPE AND CENTRAL ASIA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Board Approval Date 30-Sep-2008 Original Closing Date 30-Jun-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date Last Archived ISR Date 25-Jun-2013 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 17-Feb-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2014 Actual Mid Term Review Date 16-May-2011 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) To increase access to water supply services and to improve the quality of water supply and wastewater services in selected urban areas in six participating oblasts of the Borrower. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? ● Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Rehabilitation of water supply and sanitation systems 53.60 Support to the preparation and sustainability of investments 6.05 Project implementation and management 0.20 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Public Disclosure Authorized Overall Risk Rating Moderate Substantial Implementation Status Overview Overall progress is moderately satisfactory: disbursements have started to pick up over the last six months and are now increasing at sustained full speed. Construction activities are now back to full speed in all sub-projects under implementation. -

Festuca Arietina Klok

ACTA BIOLOGICA CRACOVIENSIA Series Botanica 59/1: 35–53, 2017 DOI: 10.1515/abcsb-2017-0004 MORPHOLOGICAL, KARYOLOGICAL AND MOLECULAR CHARACTERISTICS OF FESTUCA ARIETINA KLOK. – A NEGLECTED PSAMMOPHILOUS SPECIES OF THE FESTUCA VALESIACA AGG. FROM EASTERN EUROPE IRYNA BEDNARSKA1*, IGOR KOSTIKOV2, ANDRII TARIEIEV3 AND VACLOVAS STUKONIS4 1Institute of Ecology of the Carpathians, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 4 Kozelnytska str., Lviv, 79026, Ukraine 2Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, 64 Volodymyrs’ka str., Kyiv, 01601, Ukraine 3Ukrainian Botanical Society, 2 Tereshchenkivska str., Kyiv, 01601, Ukraine 4Lithuanian Institute of Agriculture, LT-58343 Akademija, Kedainiai distr., Lithuania Received February 20, 2015; revision accepted March 20, 2017 Until recently, Festuca arietina was practically an unknown species in the flora of Eastern Europe. Such a situa- tion can be treated as a consequence of insufficient studying of Festuca valesiaca group species in Eastern Europe and misinterpretation of the volume of some taxa. As a result of a complex study of F. arietina populations from the territory of Ukraine (including the material from locus classicus), Belarus and Lithuania, original anatomy, morphology and molecular data were obtained. These data confirmed the taxonomical status of F. arietina as a separate species. Eleven morphological and 12 anatomical characters, ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 cluster of nuclear ribo- somalKeywords: genes, as well as the models of secondary structure of ITS1 and ITS2 transcripts were studied in this approach. It was found for the first time that F. arietina is hexaploid (6x = 42), which is distinguished from all the other narrow-leaved fescues by specific leaf anatomy as well as in ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 sequences. -

Peaceful Assembly; Fair Trial; Torture, Ill-Tre

Belarus1 IHF FOCUS: freedom of expression and the media; freedom of association; peaceful assembly; fair trial; torture, ill-treatment and police misconduct; prison conditions; death penalty and disappearances; religious intolerance; conscientious objection; ethnicity; intolerance and hate speech. Belarus’ human rights record remained one of the worst in Europe, with the almost complete absence of democracy and the rule of law. High officials who had come to power by undemocratic means showed little respect for the law, and kept in motion a vicious cycle that made the situation of people living in Belarus insecure and unstable. Continued violations of political, social and economic rights created an atmosphere of fear: according to public opinion polls, almost one third of the Belarusian population were contemplating leaving the country and settling abroad. Meanwhile, Belarus faced increasing international isolation. On October 29, the last foreign staff member of the OSCE Advisory and Monitoring Group in Minsk - the officer-in-charge - left the country after the Belarusian government had refused to extend her diplomatic accreditation. Prior to that, the Belarusian authorities had successively expelled OSCE mission members while at the same time making it impossible for the mission to operate normally.2 There were almost no state institutions in Belarus whose officials were elected or appointed according to democratic procedure: most of them were appointed directly by President Aleksandr Lukashenka or his administration. As a result of non-observance of the rule of law, the power of officials increased. The Criminal Code and legislation governing economic activities allowed arbitrary accusations to be made against any person of various forms of violations and this was used to intimidate critically- minded officials and to manipulate them.