Installing Electrical Boxes and Receptacles Keep Boxes Straight and Splices Tight for Safe, Trouble-Free Circuits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dennis Morris: Pil - First Issue to Metal Box 23 March - 15 May 2016 ICA Fox Reading Room

ICA For immediate release: 13 January 2016 Dennis Morris: PiL - First Issue to Metal Box 23 March - 15 May 2016 ICA Fox Reading Room Album cover image from PiL’s first album Public Image: First Issue (1978). © Dennis Morris – all rights reserved. The ICA presents rarely seen photographs and ephemera relating to the early stages of the band Public Image Ltd’s (PiL) design from 1978-79 with a focus on the design of the album Metal Box. Original band members included John Lydon (aka Johnny Rotten - vocals), Keith Levene (lead guitar), Jah Wobble (bass) and Jim Walker (drums). Working closely with photographer and designer Dennis Morris, the display explores the evolution of the band’s identity, from their influential journey to Jamaica in 1978 to the design of the iconic Metal Box. Set against a backdrop of political and social upheaval in the UK, the years 1978-79 marked a period that hailed the end of the Sex Pistols and the subsequent shift from Punk to New Wave. Morris sought to capture this era by creating a strong visual identity for the band. His subsequent designs further aligned PiL with a style and attitude that announced a new chapter in music history. For PiL’s debut single Public Image, Morris designed a record sleeve in the format of a single folded sheet of tabloid newspaper featuring fictional content about the band. His unique approach to design was further illustrated by the debut PiL album, Public Image: First Issue (1978). In a very un-Punk manner, its cover and sleeve design imitated the layout of popular glossy magazines. -

MM" ,/ Ljtta) Fln; #-{

I99 KINGSToN RoAD LoNDON SW}g TeI,OI_540 oasi.. l 'rv MM" ,/ lJttA) fln; #-{ tru'rtterry Xffm-ry*LSS.e.Re.ffiS. seeffixss eg-ge"k&R"-4ffi *es-e cherry Red Recolds r. the Lond,on baeed, independ.ont Record. conpanyr have slgned, a three yo&r llce,'se a,greenent wtth the Sristol based gecords. Eeartbeat cherr! n"a sill-be marke! ?"d. prornote arl Eeartbeat product whicb wtli i*clud.ed, ritb cherry Redrs d,istriiutlon d.ear rriu-fp"rtan Rec ordg r First new release und,er the agreement nill be a l2,r track single by 3ristol. band. t0LAX0 4 $ersht6$ho"'A}n3.1'"]';f;i".;i'i:}'ix$i*;';;'kgr+BABrEsr wh,Lch iE rereased of stoqk for ine rait i;;; rsonthE. said raln Mc$ay on behar.f ol cherry Red,r?here are talented acts energlng f:rom tnl gristor so&e vexy will retaia totarTeY coirtioi-over &r€*r seaibeat conplo tetv ret'ain tbeir i"u*i-ii-"iiti.tbatr A. arrd, R. gid,e and havo the ad.vantage fiowever, they irr.rl 'ow of nationar *riirruutron asd havE il:fffr,tronotionaL and' markotlns raciriii.u ;;-*;;; i*,*r" ].lore luformatioa lain Uc$ay on 540 6g5I. ilrrsct*r: IeenMclrlry Registered Office, fr* S*uth .&udi*y Stre*t, fu*nc3*n W I t{u*r,r*+xl b€gK\S* €.ft*Jz-lr{ & Glaxo Babies : rliine Ilionths to the liscot (Cherry Red./ Heartbeat) Of all the new bands spawned in the Sristol area over the last few years, very few have had any lasting effect on the national scener most having dissolved into a mediochre pop/p.p soup. -

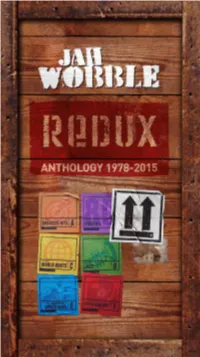

View the Redux Book Here

1 Photo: Alex Hurst REDUX This Redux box set is on the 30 Hertz Records label, which I started in 1997. Many of the tracks on this box set originated on 30 Hertz. I did have a label in the early eighties called Lago, on which I released some of my first solo records. These were re-released on 30 Hertz Records in the early noughties. 30 Hertz Records was formed in order to give me a refuge away from the vagaries of corporate record companies. It was one of the wisest things I have ever done. It meant that, within reason, I could commission myself to make whatever sort of record took my fancy. For a prolific artist such as myself, it was a perfect situation. No major record company would have allowed me to have released as many albums as I have. At the time I formed the label, it was still a very rigid business; you released one album every few years and ‘toured it’ in the hope that it became a blockbuster. On the other hand, my attitude was more similar to most painters or other visual artists. I always have one or two records on the go in the same way they always have one or two paintings in progress. My feeling has always been to let the music come, document it by releasing it then let the world catch up in its own time. Hopefully, my new partnership with Cherry Red means that Redux signifies a new beginning as well as documenting the past. -

You Disco I Freak: New Single Reviews

You Disco I Freak: New Single Reviews Music | Bittles’ Magazine: The music column from the end of the world In the second part of our two week 12” extravaganza we have all sorts of electronic goodness sure to stir the loins. There are the shiver-inducing grooves of Ghost Vision, Soela and Demuja, the progressive house wallop of Bicep, the leftfield techno of I:Cube, the classic funk of Space, a four track comp of house freshness from the Shall Not Fade crew and tons more. By JOHN BITTLES So, get the turntables ready, pop on your dancing socks, and let us begin… This week we’ll start on a high with the disco-tinged electronica of newcomers Ghost Vision’s debut EP. Thomas Gandey of Cagedbaby fame and Daniel McLewin from Balearic mavericks Psychemagik, Saturnus is out early May and contains two long, lingering downtempo grooves. Lead track Saturnus (Ghost Vision Theme) is a 13 minute long slow-burner which works its way into your very soul. With hints of John Carpenter’s soundtrack work this is a song you can easily lose yourself within for hours if not days. B-Side, Zuul Passage is every bit as good, taking its time building to a beautiful crescendo which will have your heart leaping for joy. Deeply immersive, emotive and surreal, Cologne imprint Kompakt have done it yet again with a record of rare beauty and sonic wonder. 9.5/10. Since its inception back in 2016 British label E-Beamz has been at the forefront of the leftfield house scene. -

Contents Acknowledgments Ii I. Summary 1 II. Background 2 A. Our

Contents Acknowledgments ii I. Summary 1 II. Background 2 A. Our investigation 2 B. Prior contra abuses, ambushes, kidnappings, and killings in the area 3 1. Ambushes on the highway, deaths 3 2. Executions 5 3. Kidnappings 5 C. Prior Sandinista abuses 5 D. The setting 9 1. Coperna 9 2. Military outpost at Baká Hill, Ojo de Agua 10 3. Contra presence 11 III. The Ambush 14 A. The kidnapping of two boys 14 1. Going fishing 14 2. The contras eat a cow on the Aráuz farm 14 3. The kidnapping 15 4. Evaristo Aguinaga, or Rubén 18 5. Identification of contra troops 19 B. The church vehicle and the permission given 22 C. The scene in Ojo de Agua 27 D. The ambush 31 1. The injuries 33 2. Damage to the car; ballistics 34 E. Immediately after the ambush 36 1. Immediate contact with the Baká post 36 2. The two kidnapped boys escape 37 3. The Coperna base sends out an exploratory party 38 4. The army party led by the lieutenant arrives at the scene later that night and enlists civilians to move the wounded and dead to a nearby farmhouse 40 F. The day after the ambush 42 1. The boys arrive at the Gutiérrez house 42 2. Reporting to Coperna 44 3. The dead and wounded are brought in to Siuna 45 4. State Security locates the kidnapped boys 45 VI. Conclusion 48 A. Could the Sandinistas have committed the crime? 48 B. Did the contras commit the crime? 51 iii Acknowledgments This report was written by Jemera Rone, Counsel to Americas Watch, and is based on Ms. -

Viv Albertine, Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys, Paperback, 421 Pages, London: Faber & Faber, 2014

Viv Albertine, Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys, paperback, 421 pages, London: Faber & Faber, 2014. ISBN: 978-0571297757; £14.99. Reviewed by Simon W. Goulding (Freelance, UK) The Literary London Journal, Volume 11 Number 2 (Autumn 2014) It is a truism that history is written by the winners, and even in the punk period this tended to be the men. Jon Savage’s exhaustive account of the period England’s Dreaming (1991) is great on the ale figures, the theories and the art of manipulation, but less good on the women of the period; only Vivienne Westwood comes across as an engaging and engaged figure. All the more reason to admire to Viv Albertine’s new book, which is honest, informative and entertaining. As she says: ‘I’m too outspoken for most people, they think you’re rude if you tell the truth’ (407). Albertine was the eldest child of a single mother; she grew up in Muswell Hill, made it through the secondary schools of the time into the relative haven of Art School. She got a job at Dingwalls, a key music venue of the seventies. She met Mick Jones, shared a squat with Paul Simonon, made friends with Sid Vicious, failed with the first band and then joined The Slits. This then is an account by someone who was there at the beginning of punk: I’ve crossed the line from ‘sexy wild girl just fallen out of bed’ to unpredictable, dangerous, unstable, girl’. Not so appealing. Pippi Longstocking meets Barbarella meets juvenile delinquent. -

Includes Hammers, Level, Steel Tape, Screw Drivers, Etc 2 1 Handcrafted

Prichard #2 Catalog 12/13/2019 Lot Qty Description 1 1 Box Lot of Hand Tools; includes Hammers, Level, Steel Tape, Screw Drivers, etc 2 1 Handcrafted Solid Wood Box Chest with Nine Drawers, 16x12x12, Heavy 3 1 Full Color Round Granite "Batemans Good Honest Ales" Plaque, 10" diameter 4 1 Metal Reproduction Advertising Sign "Fischer Beer", 21x15, an Old Milwaukee Beer Tray, 11" diameter, and a Inglenook 100 Year Anniversary Tray, 10" diameter 5 1 Seven Round Textile/Old Mill Spools, 6.5" to 8" tall 6 1 Group of Old Mill Shuttles; Two Converted to Candle Holders, Five are Original 7 1 Large Group of Vintage LP Record Albums; includes Joan Baez, Linda Ronstadt, Carly Simon, Diana Ross, Roberta Flack, B.B. King, and Classical Albums, etc; Approximately 45 Albums Total 8 1 Three New Recipe Notebooks, Various Styles and Designs 9 1 Large Box of Table Linens; includes Table Cloths, Napkins, etc; Many are Vintage 10 1 Wooden Oval Sheraton Serving Tray with Inlayed Medallion and Brass Handles, 24" diameter (as seen on Downton Abbey) 11 1 Wooden Red Wagon (15x9x10) with Santa Claus Figure and Two Tin Angel Candle Holders 12 1 Vintage Hand Painted Tole Trays, Various Sizes and Shapes, Approximately 12 Trays Total 13 1 Three Artificial Flowers and Plants; includes Holly Berry Tree, Snake Plant, and Amaryllis 14 1 Two Lighted Decorative Fruit Wreaths, 17" diameter each 15 1 Five Pressed Glass Items; includes Bowl (12" diameter), Cake Stand, Vase, Flower Basket Style Candy Dish, and Blue Vase 16 1 Three Pottery Pieces and Four Bone Plates; Pottery Pieces -

Service Manual

CME1356 and CME1656 INTRODUCTION This product manual contains the information Be certain that the information applies to the model needed for the setup, installation, initial start up, in question. If no model is listed, the information sanitation and maintenance of this ice machine. applies to all models. Keep it for future reference. This manual is organized in the same way as the There are 2 models covered in this manual: expected use of the machine, it begins with specifications, goes thru unpacking and setup, • CME1356, having 5 evaporators shows where everything is; continues with initial • CME1656, having 6 evaporators start up, then describes how it works. After that is the sanitation section, followed by service diagnosis and repair. TABLE OF CONTENTS Specifications .................PAGE2 Technicians Only: Harvest Cycle Operational Sequence ...................PAGE23 Air Cooled Layout ...............PAGE3 Sanitation and Cleaning ............PAGE24 Water Cooled Layout .............PAGE4 Additional Maintenance ............PAGE25 Pre-Installation .................PAGE5 Additional Maintenance: Water Distributors . PAGE 26 Location & Assembly .............PAGE6 Additional Maintenance: Inlet Water Valve Stacking ....................PAGE7 Screen .....................PAGE27 Stacking ....................PAGE8 Additional Maintenance: Ice Sensors, Condenser ........................PAGE28 Bin Control: Installation ............PAGE9 Service Diagnosis: Controller Diagnostic Light Bin Control ...................PAGE10 Analysis ....................PAGE29 -

Zoning Ordinance

ZONING ORDINANCE OAK RIDGE, TENNESSEE As Originally Passed June 17, 1959 with Amendments through December 23, 2010 OAK RIDGE CITY COUNCIL Tom Beehan, Mayor Anne Garcia Garland D. Jane Miller Tom Hayes David Mosby Charlie Hensley Ellen Smith Mark Watson, City Manager Kenneth R. Krushenski, City Attorney OAK RIDGE MUNICIPAL PLANNING COMMISSION Terry C. Domm, Chairman Chuck Agle Austin Lance Lauren Biloski Claudia Lever Linda Brown Patrick McMillan Kelly Callison Jane Shelton Charlie Hensley COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT Kathryn G. Baldwin, Director Zoning Ordinance City of Oak Ridge, TN TABLE OF CONTENTS Article I Introduction Section 1.01 Short Title ................................................................................................................................. I - 1 Section 1.02 Conflict ..................................................................................................................................... I - 1 Article II Definitions Definitions, Alphabetical Order ........................................................................................................................ II - 1 Article III General Provisions Section 3.01 General Statement of Intent .................................................................................................. III - 1 Section 3.02 General Land Use Provisions ............................................................................................... III - 2 Section 3.03 Variances to Height Limits ................................................................................................. -

Dennis Morris: Pil - First Issue to Metal Box 23 March - 15 May 2016 ICA Fox Reading Room

ICA Press release: 16 March 2016 Dennis Morris: PiL - First Issue to Metal Box 23 March - 15 May 2016 ICA Fox Reading Room Album cover image from PiL’s first album Public Image: First Issue (1978). © Dennis Morris – all rights reserved. The ICA presents rarely seen photographs and ephemera relating to the early stages of the band Public Image Ltd’s (PiL) design from 1978-79 with a focus on the design of the album Metal Box. Original band members included John Lydon (aka Johnny Rotten - vocals), Keith Levene (lead guitar), Jah Wobble (bass) and Jim Walker (drums). Working closely with photographer and designer Dennis Morris, the display explores the evolution of the band’s identity, from their influential journey to Jamaica in 1978 to the design of the iconic Metal Box. Set against a backdrop of political and social upheaval in the UK, the years 1978-79 marked a period that hailed the end of the Sex Pistols and the subsequent shift from Punk to New Wave. Morris sought to capture this era by creating a strong visual identity for the band. His subsequent designs further aligned PiL with a style and attitude that announced a new chapter in music history. For PiL’s debut single Public Image, Morris designed a record sleeve in the format of a single folded sheet of tabloid newspaper featuring fictional content about the band. His unique approach to design was further illustrated by the debut PiL album, Public Image: First Issue (1978). In a very un-Punk manner, its cover and sleeve design imitated the layout of popular glossy magazines. -

Commercial and Agricultural Estimators Worksheet Reference

COMMERCIAL AND AGRICULTURAL ESTIMATORS WORKSHEET REFERENCE June 2011 Table of Contents Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... i Overview ........................................................................................................................1 General Information .......................................................................................................4 Entering Canadian Postal Codes ................................................................................6 Additional Information ................................................................................................17 Cost Adjustments .........................................................................................................19 General Cost Adjustments .......................................................................................19 Assessment Cost Adjustments .................................................................................22 Insurance Cost Adjustments ....................................................................................23 Sections ........................................................................................................................27 Occupancies .................................................................................................................29 Occupancy Number, Name and Percentage .............................................................30 Class of -

What Is Post-Punk?

What is Post-Punk? A Genre Study of Avant-Garde Pop, 1977-1982 Mimi Haddon Schulich School of Music McGill University, Montréal April 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Ph.D. in Musicology © Mimi Haddon 2015 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... vi Résumé ......................................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................... viii List of Musical Examples ................................................................................................................ x List of Diagrams and Tables ........................................................................................................... xi List of Figures ............................................................................................................................... xii INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Genre ........................................................................................................ 4 Genre as Musical Style ..........................................................................................................