Contents Acknowledgments Ii I. Summary 1 II. Background 2 A. Our

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dennis Morris: Pil - First Issue to Metal Box 23 March - 15 May 2016 ICA Fox Reading Room

ICA For immediate release: 13 January 2016 Dennis Morris: PiL - First Issue to Metal Box 23 March - 15 May 2016 ICA Fox Reading Room Album cover image from PiL’s first album Public Image: First Issue (1978). © Dennis Morris – all rights reserved. The ICA presents rarely seen photographs and ephemera relating to the early stages of the band Public Image Ltd’s (PiL) design from 1978-79 with a focus on the design of the album Metal Box. Original band members included John Lydon (aka Johnny Rotten - vocals), Keith Levene (lead guitar), Jah Wobble (bass) and Jim Walker (drums). Working closely with photographer and designer Dennis Morris, the display explores the evolution of the band’s identity, from their influential journey to Jamaica in 1978 to the design of the iconic Metal Box. Set against a backdrop of political and social upheaval in the UK, the years 1978-79 marked a period that hailed the end of the Sex Pistols and the subsequent shift from Punk to New Wave. Morris sought to capture this era by creating a strong visual identity for the band. His subsequent designs further aligned PiL with a style and attitude that announced a new chapter in music history. For PiL’s debut single Public Image, Morris designed a record sleeve in the format of a single folded sheet of tabloid newspaper featuring fictional content about the band. His unique approach to design was further illustrated by the debut PiL album, Public Image: First Issue (1978). In a very un-Punk manner, its cover and sleeve design imitated the layout of popular glossy magazines. -

Caracterizacion Socio Economica De La Raan

Fundación para el Desarrollo Tecnológico Agropecuario y Forestal de Nicaragua (FUNICA) Fundaci ón Ford Gobierno Regional de la RAAN Caracterización socioeconómica de la Región Autónoma del Atlántico Norte (RAAN) de Nicaragua ACERCANDO AL DESARROLLO Fundación para el Desarollo Tecnológico Agropecuario y Forestal de Nicaragua (FUNICA) Fundación Ford – Gobierno Regional Elaborado por: Suyapa Ortega Thomas Consultora Revisado por: Ing. Danilo Saavedra Gerente de Operaciones de FUNICA Julio de 2009 Caracterización Socioeconómica de la RAAN 2 Fundación para el Desarollo Tecnológico Agropecuario y Forestal de Nicaragua (FUNICA) Fundación Ford – Gobierno Regional Índice de contenido Presentacion ...................................................................................................................... 5 I. Perfil general de la RAAN .............................................................................................. 7 II. Entorno regional y demografía de la RAAN.................................................................... 8 III. Organización territorial ................................................................................................ 11 3.1 Avance del proceso de demarcación y titulación .................................................... 11 IV. Caracterización de la RAAN ....................................................................................... 13 4.1 Las características hidrográficas .......................................................................... 13 Lagunas....................................................................................................................... -

REPÚBLICA DE NICARAGUA 1 Biltignia ¤£ U Kukalaya K Wakaban a Sahsa Sumubila El Naranjal Lugar Karabila L A

000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 740 750 760 770 780 790 800 810 820 830 840 850 860 870 880 Lugar Paso W a s p á m Mina Columbus Cuarenta y Tres El Paraiso Wawabun UKALAYA awa Llano Krasa K La Piedra San Miguel W La Unión Tingni 0 487 0 0 Podriwas Mani Watla 0 0 ¤£ Empalme de 0 0 Grey Town La PAlmera 0 6 Sukat Pin 6 5 5 K 451 Santa Rosa 1 REPÚBLICA DE NICARAGUA 1 Biltignia ¤£ U Kukalaya K Wakaban A Sahsa Sumubila El Naranjal Lugar Karabila L A Y MINISTERIOP laDnta EEl Sa ltoTRANSPORTE E INFRAESTRUCTURA A Leimus Dakban Risco de Oro Yulu Dakban DIEVlefaIntSe BIlaÓncoN GENERAL DE PLANIFICACIÓN Lawa Place Î La Panama Risco de Oro Kukalaya Cerro Krau Krau BONANZA B o n a n z a MAPA MUNRíIo CSucIioPAPLlan GDrandEe PRINZAPOLKA ¤£423 Rio Kukalaya W a w 414 (Amaka) Las Breñas a s ¤£ i 0 0 0 0 0 P Santa Clara 0 0 REs D VIAL INVENTARIADA POR TIPO DE SUPERFICIE 0 i P loma La 5 5 5 Murcielago Esmeralda La Potranca (Rio Sukat Pin 5 1 Industria 1 Ojochal Mukuswas Minesota Susun Arriba Kuliwas 410 Maderera o El Naranjal ¤£ A Sirpi) Y Wasminona La Luna A Españolina L A Klingna El Doce Lugar La K Susun U Potranca K El Cacao Los Placeres ¤£397 Kuliwas P u e rr tt o Klingna Landing El Corozo Empalme de C a b e z a s Wasminona ROSITA Î Karata Wihilwas El Cocal Cerro Liwatakan 0 Muelle 0 0 Bambanita 0 0 0 O 0 Cañuela Comunal 0 k 4 Buena Vista o 4 n 5 Kalmata Rio Bambana w 5 1 a 1 s Fruta de Pan La Cuesta Bambana Lugar Kalmata San Pablo de Alen B am R o s ii tt a KUKA Lapan b L a A n Y Î Omizuwas a A El Salto Lugar Betania Muelle Comunal Sulivan Wasa King Wawa Bar Cerro Wingku Waspuk Pruka 0 Lugar Kawibila 0 0 0 0 Cerro Wistiting 0 0 El Dos 0 3 San Antonio 3 5 de Banacruz 5 1 Banacruz 1 K UK A L Rio Banacruz A UKALA Y K YA Las Delicias A Banasuna Cerro Las El Sombrero Américas Pauta Bran L a El Carao y La Florida a s i Talavera k B s a Ulí am F. -

(RAAN) Cabecera Municipal SIUNA Límit

FICHA MUNICIPAL Nombre del Municipio SIUNA Región Región Autónoma del Atlántico Norte (RAAN) Cabecera Municipal SIUNA Al Norte con el Municipio de Bonanza. Al Sur con los Municipios de Paiwas y Río Blanco. Al Este con los Municipios de Rosita, Prinzapolka y Límites La Cruz de Río Grande. Al Oeste con los Municipios de Waslala y el Cua Bocay. Entre las coordenadas 13° 44' de latitud norte y 84° Posición geográfica 46' de longitud oeste Superficie 5,039.81 kms2. (INETER - 2000) Altura 200 msnm (INETER, 2000) Distancia a Managua 318 Kms. Distancia a Puerto Cabezas 218 Kms. Total 73,730 habitantes(Proyección INEC, 2000). Población Poblacion Urbana : 16.03%. Poblacion Rural: 83.97% 19.00% (FISE, 1995). Indice de Necesidades : Pobreza extrema 83.2%. Brecha de pobreza Básicas Insatisfechas: Pobres 12.1% (SAS, 1999). No pobres 4.6% I. RESEÑA HISTÓRICA Desde finales del siglo pasado se despertó el interés por la explotación de los metales preciosos en SIUNA (sobre todo el oro) por mineros particulares, artesanales, además de la actividad de comerciantes que en aquella época visitaban las comunidades indígenas de los Sumus. El municipio nace con el descubrimiento de los depósitos minerales, cuando fue puesta en marcha la explotación a pequeña escala la minería por el Señor José Aramburó en 1896. En el año 1908 empieza el auge de la búsqueda del oro, comenzando los trabajos en forma artesanal en las riberas del río SIUNAWÁS. En 1909 fue incorporada la explotación minera a la empresa La Luz SIUNA y Los Angeles Mining Company que hizo su presencia en la misma zona. -

FICHA MUNICIPAL Nombre Del Municipio PRINZAPOLKA Región

FICHA MUNICIPAL Nombre del Municipio PRINZAPOLKA Región Región Autónoma del Atlántico Norte (RAAN) Cabecera Municipal Alamikamba Al Norte: Con los municipios de Rosita y Puerto Cabezas. Al Sur : Con los municipios de la Cruz de Río Grande y Límites Desembocadura del Río Grande. Al Este : Con el Océano Atlántico (Mar Caribe). Al Oeste: Con el municipio de Siuna. Entre las coordenadas 13° 24' latitud norte y 83° 33' Posición geográfica longitud oeste. Distancia de la capital 630 Km. Superficie 7,020.48 (INETER, 2000) Altitud 5 msnm (INETER, 2000) Total 6,189 (Proyección INEC,2000). Población 490 habitantes urbanos ( 7.91%). 5,699 habitantes rurales (92.09%). 6.30% Urbano Proporción urbano/rural 93.70% Rural Brecha de pobreza 13.00% (datos del FISE, 1995) Pobres extremos 77.7%. Pobres 18.1%. Indice de Necesidades No pobres 4.2%. Básicas Insatisfechas (SAS, 1999). I. RESEÑA HISTORICA El Municipio de PRINZAPOLKA surge a finales del siglo XIX, ligado a la presencia de compañías bananeras y mineras que utilizaban el paso natural del Río PRINZAPOLKA para transportar sus productos. El nombre proviene de los Indios prinsus (de origen sumu) quienes fueron los primeros habitantes en llegar a PRINZAPOLKA al ser desalojados por los miskitos en 1860 de la Comunidad de Wankluwa, a 53 km. al sur de la barra de PRINZAPOLKA. Después del Tratado de Reincorporación de la Mosquitia a finales del siglo XIX el municipio de PRINZAPOLKA también comprendía los actuales municipios de Puerto Cabezas, Bonanza y Rosita, años después se desmembran los dos primeros y queda como sede Rosita, hoy Municipio independiente. -

MM" ,/ Ljtta) Fln; #-{

I99 KINGSToN RoAD LoNDON SW}g TeI,OI_540 oasi.. l 'rv MM" ,/ lJttA) fln; #-{ tru'rtterry Xffm-ry*LSS.e.Re.ffiS. seeffixss eg-ge"k&R"-4ffi *es-e cherry Red Recolds r. the Lond,on baeed, independ.ont Record. conpanyr have slgned, a three yo&r llce,'se a,greenent wtth the Sristol based gecords. Eeartbeat cherr! n"a sill-be marke! ?"d. prornote arl Eeartbeat product whicb wtli i*clud.ed, ritb cherry Redrs d,istriiutlon d.ear rriu-fp"rtan Rec ordg r First new release und,er the agreement nill be a l2,r track single by 3ristol. band. t0LAX0 4 $ersht6$ho"'A}n3.1'"]';f;i".;i'i:}'ix$i*;';;'kgr+BABrEsr wh,Lch iE rereased of stoqk for ine rait i;;; rsonthE. said raln Mc$ay on behar.f ol cherry Red,r?here are talented acts energlng f:rom tnl gristor so&e vexy will retaia totarTeY coirtioi-over &r€*r seaibeat conplo tetv ret'ain tbeir i"u*i-ii-"iiti.tbatr A. arrd, R. gid,e and havo the ad.vantage fiowever, they irr.rl 'ow of nationar *riirruutron asd havE il:fffr,tronotionaL and' markotlns raciriii.u ;;-*;;; i*,*r" ].lore luformatioa lain Uc$ay on 540 6g5I. ilrrsct*r: IeenMclrlry Registered Office, fr* S*uth .&udi*y Stre*t, fu*nc3*n W I t{u*r,r*+xl b€gK\S* €.ft*Jz-lr{ & Glaxo Babies : rliine Ilionths to the liscot (Cherry Red./ Heartbeat) Of all the new bands spawned in the Sristol area over the last few years, very few have had any lasting effect on the national scener most having dissolved into a mediochre pop/p.p soup. -

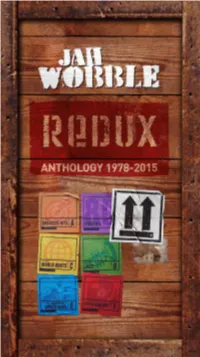

View the Redux Book Here

1 Photo: Alex Hurst REDUX This Redux box set is on the 30 Hertz Records label, which I started in 1997. Many of the tracks on this box set originated on 30 Hertz. I did have a label in the early eighties called Lago, on which I released some of my first solo records. These were re-released on 30 Hertz Records in the early noughties. 30 Hertz Records was formed in order to give me a refuge away from the vagaries of corporate record companies. It was one of the wisest things I have ever done. It meant that, within reason, I could commission myself to make whatever sort of record took my fancy. For a prolific artist such as myself, it was a perfect situation. No major record company would have allowed me to have released as many albums as I have. At the time I formed the label, it was still a very rigid business; you released one album every few years and ‘toured it’ in the hope that it became a blockbuster. On the other hand, my attitude was more similar to most painters or other visual artists. I always have one or two records on the go in the same way they always have one or two paintings in progress. My feeling has always been to let the music come, document it by releasing it then let the world catch up in its own time. Hopefully, my new partnership with Cherry Red means that Redux signifies a new beginning as well as documenting the past. -

You Disco I Freak: New Single Reviews

You Disco I Freak: New Single Reviews Music | Bittles’ Magazine: The music column from the end of the world In the second part of our two week 12” extravaganza we have all sorts of electronic goodness sure to stir the loins. There are the shiver-inducing grooves of Ghost Vision, Soela and Demuja, the progressive house wallop of Bicep, the leftfield techno of I:Cube, the classic funk of Space, a four track comp of house freshness from the Shall Not Fade crew and tons more. By JOHN BITTLES So, get the turntables ready, pop on your dancing socks, and let us begin… This week we’ll start on a high with the disco-tinged electronica of newcomers Ghost Vision’s debut EP. Thomas Gandey of Cagedbaby fame and Daniel McLewin from Balearic mavericks Psychemagik, Saturnus is out early May and contains two long, lingering downtempo grooves. Lead track Saturnus (Ghost Vision Theme) is a 13 minute long slow-burner which works its way into your very soul. With hints of John Carpenter’s soundtrack work this is a song you can easily lose yourself within for hours if not days. B-Side, Zuul Passage is every bit as good, taking its time building to a beautiful crescendo which will have your heart leaping for joy. Deeply immersive, emotive and surreal, Cologne imprint Kompakt have done it yet again with a record of rare beauty and sonic wonder. 9.5/10. Since its inception back in 2016 British label E-Beamz has been at the forefront of the leftfield house scene. -

Lecciones Del Programa Campesino a Campesino De Siuna, Nicaragua

Lecciones del Programa Campesino a Campesino de Siuna, Nicaragua Programa Salvadoreño de Investigación sobre Desarrollo y Medio Ambiente Salvadoran Development and Environment Research Program Contexto, logros y desafíos Diagramación : Leonor González Diseño Gráfico : gpremper diseño/Leonor González Fotografías : PRISMA, Kukra Hill, Adrián López y PCaC Revisión : Sandra Rodríguez © Fundación PRISMA www.prisma.org.sv [email protected] 3a. Calle Poniente No. 3760, Colonia Escalón, San Salvador Tels.: (503) 2 298 6852, (503) 2 298 6853, (503) 2 224 3700; Fax: (503) 2 2237209 Dirección Postal: Apartado 01-440, San Salvador, El Salvador, C. A. International Mailing Address: VIP No. 992, P.O. Box 52-5364, Miami FLA 33152, U.S.A. Programa Campesino a Campesino de Siuna, Nicaragua: Contexto, logros y desafíos Nelson Cuéllar y Susan Kandel Metodología y Reconocimientos Este trabajo forma parte de un esfuerzo colaborativo de PRISMA en el marco del Proyecto “Aprendiendo a Construir Modelos de Acompañamiento para Organizaciones Forestales de Base en Brasil y Centroamérica”, apoyado por la Fundación Ford y ejecutado conjuntamente por el Centro Internacional de Investigación Forestal (CIFOR, por sus siglas en inglés) y la Asociación Coordinadora Indígena y Campesina de Agroforestería Comunitaria Centroameri- cana (ACICAFOC) que opera como ejecutor del proyecto en Centroamérica. En este trabajo se combinó la revisión documental con información secundaria; la revisión de documentos primarios; y el trabajo de campo en Siuna (abril de 2004) que incluyó la participa- ción en talleres con líderes, productores, promotores y autosistematizadores comunitarios; así como entrevistas con líderes del PCaC de Siuna e informantes en ese municipio y en Mana- gua. -

Interviews in La Libertad and Bonanza, Nicaragua – August 2001 Conducted, Transcribed, and Translated by Anneli Tolvanen

Interviews in La Libertad and Bonanza, Nicaragua – August 2001 Conducted, transcribed, and translated by Anneli Tolvanen Contents: Foreword – March, 2003:..........................................................................................................2 Interviews in La Libertad, Chontales, Nicaragua...............................................................................2 Interview with Darwin Kauffman, President of the Small-scale miners cooperative of La Libertad (COOPPEMILICH) – August 9, 2001 .........................................................................................2 Interview with Darwin Kauffman, President of the Small-Scale Miners’ Cooperative (COOPPEMILICH) in La Libertad – Part II .................................................................................................................5 Interviews with Senior Students at the High School in La Libertad – August 9, 2001 ............................... 10 Interview with Amacio Anizal (small-scale miner and former secretary of the Small Miners’ Cooperative, COOPPEMILICH) – August 9, 2001 ........................................................................................ 15 Interview with Cristina Gonzalez Reyes, Small-scale miner.............................................................. 18 Interview with Victor Garcia Roja in the General Store “Adelina”..................................................... 20 Interview with René Leiva, small-scale miner .............................................................................. 21 Interview -

Agriculture in Nicaragua: Performance, Challenges, and Options Public Disclosure Authorized November, 2015

102989 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Agriculture in Nicaragua: Performance, Challenges, and Options Public Disclosure Authorized November, 2015 INTERNATIONAL FUND FOR AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work with- out permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Develop- ment/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete informa- tion to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978- 750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. -

Viv Albertine, Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys, Paperback, 421 Pages, London: Faber & Faber, 2014

Viv Albertine, Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys, paperback, 421 pages, London: Faber & Faber, 2014. ISBN: 978-0571297757; £14.99. Reviewed by Simon W. Goulding (Freelance, UK) The Literary London Journal, Volume 11 Number 2 (Autumn 2014) It is a truism that history is written by the winners, and even in the punk period this tended to be the men. Jon Savage’s exhaustive account of the period England’s Dreaming (1991) is great on the ale figures, the theories and the art of manipulation, but less good on the women of the period; only Vivienne Westwood comes across as an engaging and engaged figure. All the more reason to admire to Viv Albertine’s new book, which is honest, informative and entertaining. As she says: ‘I’m too outspoken for most people, they think you’re rude if you tell the truth’ (407). Albertine was the eldest child of a single mother; she grew up in Muswell Hill, made it through the secondary schools of the time into the relative haven of Art School. She got a job at Dingwalls, a key music venue of the seventies. She met Mick Jones, shared a squat with Paul Simonon, made friends with Sid Vicious, failed with the first band and then joined The Slits. This then is an account by someone who was there at the beginning of punk: I’ve crossed the line from ‘sexy wild girl just fallen out of bed’ to unpredictable, dangerous, unstable, girl’. Not so appealing. Pippi Longstocking meets Barbarella meets juvenile delinquent.