Ingrid Rembold, Conquest and Christianization: Saxony and the Carolingian World, 772- 888

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dokument Öffnen (3.7MB)

Super alta perennis Studien zur Wirkung der Klassischen Antike Band 11 Herausgegeben von Uwe Baumann, Marc Laureys und Winfried Schmitz Matthias Becher / Alheydis Plassmann (Hg.) Streit am Hof im frühen Mittelalter Mit 12 Abbildungen V&R unipress Bonn University Press Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-89971-884-3 ISBN 978-3-86234-884-8 (E-Book) Veröffentlichungen der Bonn University Press erscheinen im Verlag V&R unipress GmbH. Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft. 2011, V&R unipress in Göttingen / www.vr-unipress.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk und seine Teile sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung in anderen als den gesetzlich zugelassenen Fällen bedarf der vorherigen schriftlichen Einwilligung des Verlages. Printed in Germany. Titelbild: Blendung Leos III. aus der Sächsischen Weltchronik, Ms. a. 33, fol. 57v (Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Bremen) Druck und Bindung: CPI Buch Bücher.de GmbH, Birkach Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier. Inhalt Danksagung . ................................ 7 Matthias Becher Gedanken zur Einführung . ......................... 9 Daniel G. König Öffentliche religiöse Auseinandersetzungen unter Beteiligung spätantik-frühmittelalterlicher Höfe – Versuch einer Typologie ...... 17 Roland Steinacher Der vandalische Königshof -

Glansdorff Comites.Pdf

Instrumenta Bd. 20 2011 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online- Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. Comites in regno Hludouici regis constituti Prosopographie des détenteurs d’offices séculiers en Francie orientale, de Louis le Germanique à Charles le Gros 826–887 779209_umbr.indd9209_umbr.indd 1 229.09.119.09.11 007:327:32 INSTRUMENTA Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Historischen Institut Paris Band 20 COMITES IN REGNO HLUDOUICI REGIS CONSTITUTI Prosopographie des détenteurs d’offices séculiers en Francie orientale, de Louis le Germanique à Charles le Gros 826–887 Jan Thorbecke Verlag 779209_umbr.indd9209_umbr.indd 2 229.09.119.09.11 007:327:32 COMITES IN REGNO HLUDOUICI REGIS CONSTITUTI Prosopographie des détenteurs d’offices séculiers en Francie orientale, de Louis le Germanique à Charles le Gros 826–887 Éditée par Sophie Glansdorff Jan Thorbecke Verlag 779209_umbr.indd9209_umbr.indd 3 229.09.119.09.11 007:327:32 INSTRUMENTA Herausgeberin: Prof. Dr. Gudrun Gersmann Redaktion: Veronika Vollmer Deutsches Historisches Institut, Hôtel Duret-de-Chevry, 8, rue du Parc-Royal, F-75003 Paris Institutslogo: Heinrich Paravicini, unter Verwendung eines Motivs am Hôtel Duret-de-Chevry Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. -

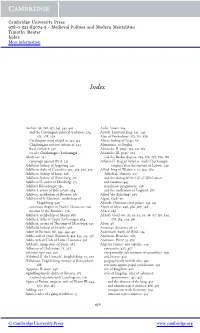

Medieval Polities and Modern Mentalities Timothy Reuter Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82074-5 - Medieval Polities and Modern Mentalities Timothy Reuter Index More information Index Aachen: 96, 128, 137, 145, 343, 425 Airlie, Stuart: 224 and the Carolingian political tradition: 274, Aistulf, Lombard king: 232, 242 275, 278, 279 Alan of Tewkesbury: 171, 172, 176 Carolingian royal chapel at: 141, 142 Albert, bishop of Liege:` 66 Charlemagne receives tribute at: 234 Alemannia: see Swabia fiscal complex: 337 Alexander II, pope: 150, 151, 162 see also Charlemagne; Lotharingia Alexander III, pope: 204 Abodrites: 232 and the Becket dispute: 174, 176, 177, 180, 186 campaign against (892): 221 Alfonso II, king of Asturias: sends Charlemagne Adalbero, bishop of Augsburg: 225 trophies after the capture of Lisbon: 240 Adalbero, duke of Carinthia: 202, 363, 372, 379 Alfred, king of Wessex: 5, 15, 140, 280 Adalbero, bishop of Laon: 228 ‘Alfredian’ charters: 297 Adalbero, bishop of Wurtzburg:¨ 371 and the dating of the Life of Alfred: 10–11 Adalbero II, count of Ebersberg: 375 and taxation: 445 Adalbert Babenberger: 114 translation programme: 298 Adalbert, count of Ballenstedt: 364 and the unification of England: 287 Adalbert, archbishop of Bremen: 385 Alfred ‘the Ætheling’: 290 Adalbert of St Maximin, archbishop of Algazi, Gadi: 115 Magdeburg: 340 Allstedt, Ottonian royal palace: 141, 142 continues Regino of Prum’s¨ Chronicon: 290 Alpert of Metz: 146, 366, 367, 398 mission to the Russians: 276 Alsace: 286 Adalbert, archbishop of Mainz: 380 Althoff, Gerd: 90, 91, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 130, 144, Adalbert, -

Conquest and Colonization in the Early Middle Ages: the Carolingians and Saxony, C

Conquest and Colonization in the Early Middle Ages: The Carolingians and Saxony, c. 751–842 by Christopher Thomas Landon A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Christopher Thomas Landon 2017 Conquest and Colonization in the Early Middle Ages: The Carolingians and Saxony, c. 751–842 Christopher Thomas Landon Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto 2017 Abstract This thesis reconsiders longstanding questions regarding the economic and ideological forces that drove Frankish expansion into Saxony in the late eighth and early ninth centuries, Frankish strategies of rule in the newly conquered region, and the effects of conquest and cultural disposession on the Saxons themselves. Specifically, the dissertation seeks to present a new interpretation of this critical historical episode as a process of colonization. After an introduction that briefly outlines various conceptions and definitions of colonization and how these apply to the early medieval period, chapter one provides an overview of the main Latin and Old Saxon sources regarding Saxony and the Saxons in the Carolingian period from the coronation of Pippin III to the suppression of the Saxon Stellinga uprising in 842. The chapter emphasizes the tendentious nature of these sources and the ways in which they reflect the perspective of the colonizer while obscuring the experiences of the colonized. Chapter two looks at the ideological justifications for the conquest advanced in the Frankish primary sources, arguing that the Franks’ forcible Christianization of the Saxons was driven in part by the Carolingian dynasty’s increasingly close ties with the papacy and by ancient imperial prerogatives regarding the extension of the faith. -

“Unconquered Louis Rejoiced in Iron”: Military History in East Francia Under King Louis the German (C. 825-876) a Dissertat

“Unconquered Louis Rejoiced In Iron”: Military History in East Francia under King Louis the German (c. 825-876) A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Minnesota By Christopher Patrick Flynn In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Advised by Dr. Bernard S. Bachrach May 2020 Copyright © 2020 Christopher P. Flynn All Rights Reserved i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have accrued huge debts in the creation of this work, which will not be adequately repaid by mention here. I must thank the faculty of the University of Minnesota, particularly the Department of History and the Department of Classical and Near Eastern Studies. Thanks are especially due to my committee members, Drs. Bernard Bachrach, Kathryn Reyerson, Andrew Gallia, Michael Lower, and Oliver Nicholson, as well as to Drs. Howard Louthan and Gary Cohen, both of whom served as Director of the Center for Austrian Studies during my tenure there. I thank the office staff of the history department for navigating endless paperwork on my behalf, as well as the University of Minnesota library system for acquiring copies of difficult to find works and sources in several languages. Especially, among these numerous contributors, I thank my adviser Dr. Bachrach, whose work was the reason I came to Minnesota in the first place, and whose support and erudition made the journey worth it. In this regard, I thank Dr. Lorraine Attreed of the College of the Holy Cross, who not only introduced me to the deeply fascinating world of early medieval Europe, but also exposed me to the work of Dr. -

Der Munizipalsozialismus in Europa

Revolte und Sozialstatus Révolte et statut social Pariser Historische Studien herausgegeben vom Deutschen Historischen Institut Paris Band 87 R. Oldenbourg Verlag München 2008 Revolte und Sozialstatus von der Spätantike bis zur Frühen Neuzeit Révolte et statut social de l’Antiquité tardive aux Temps modernes herausgegeben von Philippe Depreux R. Oldenbourg Verlag München 2008 Pariser Historische Studien Herausgeberin: Prof. Dr. Gudrun GERSMANN Redaktion: Veronika VOLLMER Institutslogo: Heinrich PARAVICINI, unter Verwendung eines Motivs am Hôtel Duret-de-Chevry Anschrift: Deutsches Historisches Institut (Institut historique allemand) Hôtel Duret-de-Chevry, 8, rue du Parc-Royal, F-75003 Paris Publiziert mit Unterstützung der Mission historique française en Allemagne Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.d-nb.de> abrufbar. © 2008 Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH, München Rosenheimer Straße 145, D-81671 München Internet: oldenbourg.de Das Werk einschließlich aller Abbildungen ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages un- zulässig und strafbar. Dies gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikro- verfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Bearbeitung in elektronischen Systemen. Umschlaggestaltung: Dieter Vollendorf, München Gedruckt auf säurefreiem,