Music That Laughs 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![The Floozies Free Download [TSIS PREMIERE] Griz Announces All Good Records and Releases New Floozies Single As Free Download](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8281/the-floozies-free-download-tsis-premiere-griz-announces-all-good-records-and-releases-new-floozies-single-as-free-download-88281.webp)

The Floozies Free Download [TSIS PREMIERE] Griz Announces All Good Records and Releases New Floozies Single As Free Download

the floozies free download [TSIS PREMIERE] GRiZ Announces All Good Records And Releases New Floozies Single As Free Download. GRiZ who is one of the pioneers of the electro-soul and future funk sounds, along with artists like Pretty Lights and Gramatik, yet has managed to carve his own lane in the genre. The always impressive artist announced his own record label 2 years ago with the release of his most recent album Rebel Era which was put out as a free download as well as being on iTunes. Today, the artist is announcing a new chapter in his career with the closing of Liberated Music and the launch of All Good Records. This label, while still carrying out releases being freely available, is also a step in the direction of a full service record label as opposed to just an avenue for Grant (Griz) to distribute his own work. The label has two signed artists, mid west live funk duo The Floozies and Chicago based soul star and TSIS regular Manic Focus . You can now follow the new All Good Records on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook, but you should also visit the freshly launched website www.AllGoodRecords.com where you can hear a preview of a new GRiZ song which we can expect to see on his upcoming album Say It Loud that is dropping soon. Also to celebrate the launch, we have the latest single from the newly reformed labels' first release, The Floozies upcoming album Do Your Thing which will be released Jan 27th. We premiered "FNKTRP" and "Fantastic Love" from the group and now have an exclusive first listen of the song "She Ain't Yo Girlfriend" which captures the signature funky Floozies sound, yet is delivered in an extra sensual manner. -

Synthwave Muzikos Stilius: Keistumas Ir Hiperrealybė

LIETUVOS MUZIKOS IR TEATRO AKADEMIJA MUZIKOS FAKULTETAS KOMPOZICIJOS KATEDRA Martynas Kraujalis SYNTHWAVE MUZIKOS STILIUS: KEISTUMAS IR HIPERREALYBĖ Studijų programa: kompozicija (skaitmeninės technologijos) Magistro tiriamasis darbas Darbo autorius: Martynas Kraujalis (parašas) Darbo vadovas: Lekt. dr. Jonas Jurkūnas (parašas) Vilnius, 2020 LIETUVOS MUZIKOS IR TEATRO AKADEMIJA BAIGIAMOJO DARBO SĄŽININGUMO DEKLARACIJA 20____m. _____________ __ d. Patvirtinu, kad mano tiriamasis rašto darbas (tema) „SYNTHWAVE MUZIKOS STILIUS: KEISTUMAS IR HIPERREALYBĖ“, yra parengtas savarankiškai. 1. Šiame darbe pateikta medžiaga nėra plagijuota, tyrimų duomenys yra autentiški ir nesuklastoti. 2. Tiesiogiai ar netiesiogiai panaudotos kitų šaltinių ir/ar autorių citatos ir/ar kita medžiaga pažymėta literatūros nuorodose arba įvardinta kitais būdais. 3. Kitų asmenų indėlio į parengtą baigiamąjį darbą nėra. 4. Jokių įstatymų nenumatytų piniginių sumų už šį darbą niekam nesu mokėjęs (-usi). 3. Su pasekmėmis, nustačius plagijavimo ar duomenų klastojimo atvejus, esu susipažinęs(- usi) ir jas suprantu. ______________ ______________________ Parašas (Vardas, pavardė) 2 Martynas Kraujalis Synthwave muzikos stilius: keistumas ir hiperrealybė Santrauka Synthwave muzika: saviraiška ir postmodernistinis muzikinis judėjimas. Hiperrealybė – geresnis pasaulio sukūrimas teikiantis daugiau laimės nei tikras. Retro-futuristnė ateitis, kuri niekada taip ir neįvyko, tačiau šiandien apie ją galvojama kaip apie geresnį hiperrealų pasaulį, geresnį gyvenimą į kurį norisi grįžti nors jo niekada ir nebuvo. Sintezatoriai ir bitcrush: Synthwave muzikos pagrindiniai elementai kurie imituoja tų laikų stilistiką: bitcrush 1980 -ais metais buvo trūkumas, dabar tai didelė Synthwave stiliaus dalis. Elektroninis sintezatoriaus garsas tampa hiperrealybės terpės imitacija. Mėlyna Synthwave spalva: žmogaus troškimas kontaktuoti su dieviškąja būtybe – hiperrealybė. Synthwave muzika ir kaip keistai į tai reaguoja klausytojas: reakcija į keistumą sukuria dar vieną Synthwave klausymo pojūtį, estetinį Synthwave suvokimą. -

Exploring Queer Expressions in Mens Underwear Through Post Internet Aesthetic As Vaporwave

Mens underwear :Exploring queer expressions in mens underwear through post internet aesthetic as Vaporwave. Master in fashion design Mario Eurenius 2018.6.09. 1. Abstract This work explores norms of dress design by the use of post internet aesthetics in mens underwear. The exploration of underwear is based on methods formed to create a wider concept of how mens underwear could look like regarding shape, color, material and details. Explorations of stereotypical and significant elements of underwear such as graphics and logotypes has been reworked to create a graphical identity bound to a brand. This is made to contextualize the work aiming to present new options and variety in mens underwear rather than stating examples using symbols or stereotypic elements. In the making of the examples for this work the process goes front and back from digital to physical using different media to create compositions of color, graphic designs and outlines using transfer printer, digital print, and laser cutting machine. Key words: Mens underwear, graphic, colour, norm, identity, post internet, laser cut. P: P: 2 Introduction to the field 3 Method 15 What is underwear? 39 Shape, Rough draping Historical perspective 17 Male underwear and nudity 41 From un-dressed to dressed 18 Graphics in fashion and textiles 42 Illustrator sketching 19 Differencesin type and categories of mensunderwear 43 shape grapich design 2,1 Background 3.1 Developement 45 collection of pictures 49 Colour 20 Vaporwave 50 Rough draping Japanese culture 21 Mucis 55 Rough draping 2 22 -

RE-ANIMATING GHOSTS MATERIALITY and MEMORY in HAUNTOLOGICAL APPROPRIATION Abstract

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF FILM AND MEDIA ARTS (2019) Vol. 4, Nº. 2 pp. 24-37 © 2019 BY-NC-ND ijfma.ulusofona.pt DOI: 10.24140/ijfma.v4.n2.02 RE-ANIMATING GHOSTS MATERIALITY AND MEMORY IN HAUNTOLOGICAL APPROPRIATION Abstract This research examines the spectrality of an- MICHAEL PETER SCHOFIELD imation and other media based on the photo- graphic trace. Using diverse examples from pop- ular culture and the author’s own investigative practice in media art, this paper looks at how ar- chival media is re-used and can be brought back to life in new moving image works, in a gesture we might call hauntological appropriation. While sampling and re-using old materials is nothing new, over the last 15 years we have seen an ongoing tendency to foreground the ghostly qualities of vintage recordings and found foot- age, and a recurrent fetishisation and simula- tion of obsolete technologies. Here we examine the philosophies and productions behind this hauntological turn and why the materiality of still and moving image media has become such a focus. We ask how that materiality effects the machines that remember for us, and how we re- use these analogue memories in digital cultures. Due to the multimodal nature of the author’s creative practice, photography, video art, doc- umentary film and animation, are interrogated here theoretically. Re-animating the ghosts of old media can reveal ontological differences between these forms, and a ghostly synergy be- tween the animated and the photographic. Keywords: hauntology, animation, memory, media * University of Leeds, United Kingdom archaeology, appropriation, ontology, animated [email protected] documentary 24 RE-ANIMATING GHOSTS MICHAEL PETER SCHOFIELD Every culture has its phantoms and the spectral- how we can foreground their specific materiality, and the ity that is conditioned by its technology (Derrida, haunting associations with personal and cultural memory Amelunxen, Wetzel, Richter, & Fort, 2010, p. -

Metamodernism and Vaporwave: a Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 14 | Issue 1 Article 3 Metamodernism and Vaporwave: A Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture Nicholas Morrissey University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh Recommended Citation Morrissey, Nicholas. “Metamodernism and Vaporwave: A Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture.” Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology 14, no. 1 (2021): 64-82. https://doi.org/10.5206/notabene.v14i1.13361. Metamodernism and Vaporwave: A Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture Abstract With the advent of Web 2.0, new forms of cultural and aesthetic texts, including memes and user generated content (UGC), have become increasingly popular worldwide as streaming and social media services have become more ubiquitous. In order to acknowledge the relevance and importance of these texts in academia and art, this paper conducts a three-part analysis of Vaporwave—a unique multimedia style that originated within Web 2.0—through the lens of a new cultural philosophy known as metamodernism. Relying upon a breadth of cultural theory and first-hand observations, this paper questions the extent to which Vaporwave is interested in metamodernist constructs and asks whether or not the genre can be classed as a metamodernist text, noting the dichotomy and extrapolation of nostalgia promoted by the genre and the unique instrumentality it offers to its consumers both visually and sonically. This paper ultimately theorizes that online culture will continue to play an important role in cultural production, aesthetic mediation, and even -

The Social Significance of Modern Trademarks: Authorizing the Appropriation of Marks As Source Identifiers for Expressive Works*

YAQUINTO.TOPRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 2/8/2017 11:25 AM The Social Significance of Modern Trademarks: Authorizing the Appropriation of Marks as Source Identifiers for * Expressive Works Dieuson Octave is a nineteen-year-old rapper from Florida that recently signed a deal with Atlantic Records. His YouTube videos have millions of views. He releases his music under the name Kodak Black. Some graffiti writers use stickers in addition to spray paint. In San Francisco, a writer named Ther had stickers appropriating the The North Face logo. Instead of reading The North Face in stacked type, Ther’s stickers read “Ther Norco Face.” Norco is a brand of prescription painkiller. Vaporwave is an obscure genre of music. Largely sample-based, it is characterized by an obsession with retro aesthetics, new technology, and consumerism. Songs range from upbeat to hypnogogic. They sometimes incorporate sound marks. Vaporwave musicians have monikers like Saint Pepsi and Macintosh Plus. Gucci Mane is a rap star and actor from Atlanta. All nine of his studio albums have placed on the Billboard Top 200. In 2013, he starred alongside James Franco and Selena Gomez in Spring Breakers, which competed for the Golden Lion award at the sixty-ninth Venice International Film Festival. Stuart Helm is an artist who formerly used the moniker King VelVeeda. Until the early 2000s, he operated cheeseygraphics.com, a website that sold his bawdy-themed art and advertised commercial art services. Horst Simco is a recording artist from Houston who goes by Riff Raff. His collection of tattoos includes the NBA logo, the MTV logo, and the BET logo. -

Blssm Paper Artist Statement

!1 of !7 Simon DeBevoise Artist Statement Prof. Maria Sonevytsky 12.12.15 blssm: An Exploration of Cuteness, Consumer Culture and PC Music blssm is an experiment in aesthetics. Tackling a genre of unlimited ambition and excess, I realized quickly that my project could not be a limp imitation of PC Music; the music mandates instead a full-fledged devotion to the “kitsch imagery, catchy hooks, synthetic colours” (Tank Magazine, AG Cook) so central to figures like AG Cook, Hannah Diamond, SOPHIE and GFOTY. I used Hannah Diamond’s “Every Night” as an aural point of reference, reinterpreting the song’s poppy chord progression and setting my tempo to an upbeat 128 bpm. Layering big, shimmering, sawtooth synths over a syncopated kick drum and bass, I created a foundation with which I could engage with the camp and consumerism typically antithetical to the underground music scene yet so integral to the PC Music label. Recreating PC Music’s visual and aural aesthetic, I aim to consider the issues of gender and sexuality at play by framing the genre within discourses on Studio Audio Art, Cyborg Feminism, Japanese Kawaii culture, consumerism, and post-irony. To best introduce the uninformed listener to PC Music (which, importantly, stands for computer music and not politically correct music), I’ve included lyrics from Hannah Diamond’s “Pink and Blue:” We look good in pink and blue You love me, maybe it's true You say, ‘Baby, how are you?’ I’m okay, how about you? DeBevoise !2 of !7 Diamond’s facile rhymes and innocent lyrics craft an image of cuteness and middle-school naivety that play into PC Music’s brand of femininity. -

A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2018-07-01 El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Wilkins, Rex Richard, "El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 6997. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6997 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk Culture in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Brian Price, Chair Erik Larson Alvin Sherman Department of Spanish and Portuguese Brigham Young University Copyright © 2018 Rex Richard Wilkins All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk Culture in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins Department of Spanish and Portuguese, BYU Master of Arts This thesis examines the punk genre’s evolution into commercial mainstream music in Spain and Mexico. It looks at how this evolution altered both the aesthetic and gesture of the genre. This evolution can be seen by examining four bands that followed similar musical and commercial trajectories. -

Narcocorridos As a Symptomatic Lens for Modern Mexico

UCLA Department of Musicology presents MUSE An Undergraduate Research Journal Vol. 1, No. 2 “Grave-Digging Crate Diggers: Retro “The Narcocorrido as an Ethnographic Fetishism and Fan Engagement with and Anthropological Lens to the War Horror Scores” on Drugs in Mexico” Spencer Slayton Samantha Cabral “Callowness of Youth: Finding Film’s “This Is Our Story: The Fight for Queer Extremity in Thomas Adès’s The Acceptance in Shrek the Musical” Exterminating Angel” Clarina Dimayuga Lori McMahan “Cats: Culturally Significant Cinema” Liv Slaby Spring 2020 Editor-in-Chief J.W. Clark Managing Editor Liv Slaby Review Editor Gabriel Deibel Technical Editors Torrey Bubien Alana Chester Matthew Gilbert Karen Thantrakul Graphic Designer Alexa Baruch Faculty Advisor Dr. Elisabeth Le Guin 1 UCLA Department of Musicology presents MUSE An Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 1, Number 2 Spring 2020 Contents Grave-Digging Crate Diggers: Retro Fetishism and Fan Engagement 2 with Horror Scores Spencer Slayton Callowness of Youth: Finding Film’s Extremity in Thomas Adès’s 10 The Exterminating Angel Lori McMahan The Narcocorrido as an Ethnographic and Anthropological Lens to 18 the War on Drugs in Mexico Samantha Cabral This Is Our Story: The Fight for Queer Acceptance in Shrek the 28 Musical Clarina Dimayuga Cats: Culturally Significant Cinema 38 Liv Slaby Contributors 50 Closing notes 51 2 Grave-Digging Crate Diggers: Retro Fetishism and Fan Engagement with Horror Scores Spencer Slayton he horror genre is in the midst of a renaissance. The slasher craze of the late 70s and early 80s, revitalized in the mid-90s, is once again a popular genre for Treinterpretation by today’s filmmakers and film composers. -

University of Birmingham from Microsound to Vaporwave

University of Birmingham From Microsound to Vaporwave Born, Georgina; Haworth, Christopher DOI: 10.1093/ml/gcx095 Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Born, G & Haworth, C 2018, 'From Microsound to Vaporwave: internet-mediated musics, online methods, and genre', Music and Letters, vol. 98, no. 4, pp. 601–647. https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcx095 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility: 30/03/2017 This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Music and Letters following peer review. The version of record Georgina Born, Christopher Haworth; From Microsound to Vaporwave: Internet-Mediated Musics, Online Methods, and Genre, Music and Letters, Volume 98, Issue 4, 1 November 2017, Pages 601–647 is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcx095 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

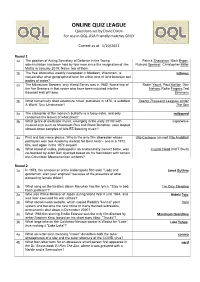

ONLINE QUIZ LEAGUE Questions Set by David Dixon for Use in OQL-USA Friendly Matches ONLY

ONLINE QUIZ LEAGUE Questions set by David Dixon For use in OQL-USA Friendly matches ONLY Correct as at 1/10/2021 Round 1 1a The position of Acting Secretary of Defense in the Trump Patrick Shanahan, Mark Esper, administration has been held by four men since the resignation of Jim Richard Spencer, Christopher Miller Mattis in January 2019. Name two of them 1b The free alternative weekly newspaper in Madison, Wisconsin, is Isthmus named after what geographical term for a thin strip of land between two bodies of water? 2a The Milwaukee Brewers' only World Series was in 1982. Name two of Robin Yount, Paul Molitor, Don the five Brewers in that roster who have been inducted into the Nelson, Rollie Fingers,Ted Baseball Hall of Fame. Simmons 2b What numerically titled adventure novel, published in 1870, is subtitled Twenty Thousand Leagues Under A World Tour Underwater? The Sea 3a The caterpillar of the monarch butterfly is a fussy eater, and only milkweed consumes the leaves of what plant? 3b What genre of electronic music, emerging in the early 2010s with vaporwave musical acts such as Macintosh Plus and Blank Banshee, uses looped, slowed-down samples of 80s EZ-listening music? 4a First and last name please. Who is the only film character whose Vito Corleone (accept Vito Andolini) portrayals won two Academy Awards for Best Actor-- one in a 1972 film, and again in the 1974 sequel? 4b What brand of vodka, packaged in an anatomically-correct bottle, was Crystal Head (NOT Skull) co-founded by actor Dan Aykroyd based on his fascination with certain -

The Music (And More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report

The Music (and More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report Report covers the time period of July 1st to Kieran Robbins & Chief - "Sway" [glam rock] September 30th, 2019. I inadvertently missed Troy a few before that time period, which were brought to my attention by fans, bands & Moriah Formica - "I Don't Care What You others. The missing are listed at the end, along with an Think" (single) [hard rock] Albany End Note… Nine Votes Short - "NVS: 09/03/2019" [punk rock] RECORDINGS: Albany Hard Rock / Metal / Punk Psychomanteum - "Mortal Extremis" (single track) Attica - "Resurected" (EP) [hardcore metal] Albany [thrash prog metal industrial] Albany Between Now and Forever - "Happy" (single - Silversyde - "In The Dark" [christian gospel hard rock] Mudvayne cover) [melodic metal rock] Albany Troy/Toledo OH Black Electric - "Black Electric" [heavy stoner blues rock] Scotchka - "Back on the Liquor" | "Save" (single tracks) Voorheesville [emo pop punk] Albany Blood Blood Blood - "Stranglers” (single) [darkwave Somewhere To Call Home - "Somewhere To Call Home" horror synthpunk] Troy [nu-metalcore] Albany Broken Field Runner – "Lay My Head Down" [emo pop Untaymed - "Lady" (single track) [british hard rock] punk] Albany / LA Colonie Brookline - "Live From the Bunker - Acoustic" (EP) We’re History - "We’re History" | "Pop Tarts" - [acoustic pop-punk alt rock] Greenwich "Avalanche" (singles) [punk rock pop] Saratoga Springs Candy Ambulance - "Traumantic" [alternative grunge Wet Specimens - "Haunted Flesh" (EP) [hardcore punk] rock] Saratoga Springs Albany Craig Relyea - "Between the Rain" (single track) Rock / Pop [modern post-rock] Schenectady Achille - "Superman (A Song for Mora)" (single) [alternative pop rock] Albany Dead-Lift - "Take It or Leave It" (single) [metal hard rock fusion] Schenectady Caramel Snow - "Wheels Are Meant To Roll Away" (single track) [shoegaze dreampop] Delmar Deep Slut - "u up?" (3-song) [punk slutcore rap] Albany Cassandra Kubinski - "DREAMS (feat.