The Role of Music and Sound in Neoliberal Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Queer Expressions in Mens Underwear Through Post Internet Aesthetic As Vaporwave

Mens underwear :Exploring queer expressions in mens underwear through post internet aesthetic as Vaporwave. Master in fashion design Mario Eurenius 2018.6.09. 1. Abstract This work explores norms of dress design by the use of post internet aesthetics in mens underwear. The exploration of underwear is based on methods formed to create a wider concept of how mens underwear could look like regarding shape, color, material and details. Explorations of stereotypical and significant elements of underwear such as graphics and logotypes has been reworked to create a graphical identity bound to a brand. This is made to contextualize the work aiming to present new options and variety in mens underwear rather than stating examples using symbols or stereotypic elements. In the making of the examples for this work the process goes front and back from digital to physical using different media to create compositions of color, graphic designs and outlines using transfer printer, digital print, and laser cutting machine. Key words: Mens underwear, graphic, colour, norm, identity, post internet, laser cut. P: P: 2 Introduction to the field 3 Method 15 What is underwear? 39 Shape, Rough draping Historical perspective 17 Male underwear and nudity 41 From un-dressed to dressed 18 Graphics in fashion and textiles 42 Illustrator sketching 19 Differencesin type and categories of mensunderwear 43 shape grapich design 2,1 Background 3.1 Developement 45 collection of pictures 49 Colour 20 Vaporwave 50 Rough draping Japanese culture 21 Mucis 55 Rough draping 2 22 -

RE-ANIMATING GHOSTS MATERIALITY and MEMORY in HAUNTOLOGICAL APPROPRIATION Abstract

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF FILM AND MEDIA ARTS (2019) Vol. 4, Nº. 2 pp. 24-37 © 2019 BY-NC-ND ijfma.ulusofona.pt DOI: 10.24140/ijfma.v4.n2.02 RE-ANIMATING GHOSTS MATERIALITY AND MEMORY IN HAUNTOLOGICAL APPROPRIATION Abstract This research examines the spectrality of an- MICHAEL PETER SCHOFIELD imation and other media based on the photo- graphic trace. Using diverse examples from pop- ular culture and the author’s own investigative practice in media art, this paper looks at how ar- chival media is re-used and can be brought back to life in new moving image works, in a gesture we might call hauntological appropriation. While sampling and re-using old materials is nothing new, over the last 15 years we have seen an ongoing tendency to foreground the ghostly qualities of vintage recordings and found foot- age, and a recurrent fetishisation and simula- tion of obsolete technologies. Here we examine the philosophies and productions behind this hauntological turn and why the materiality of still and moving image media has become such a focus. We ask how that materiality effects the machines that remember for us, and how we re- use these analogue memories in digital cultures. Due to the multimodal nature of the author’s creative practice, photography, video art, doc- umentary film and animation, are interrogated here theoretically. Re-animating the ghosts of old media can reveal ontological differences between these forms, and a ghostly synergy be- tween the animated and the photographic. Keywords: hauntology, animation, memory, media * University of Leeds, United Kingdom archaeology, appropriation, ontology, animated [email protected] documentary 24 RE-ANIMATING GHOSTS MICHAEL PETER SCHOFIELD Every culture has its phantoms and the spectral- how we can foreground their specific materiality, and the ity that is conditioned by its technology (Derrida, haunting associations with personal and cultural memory Amelunxen, Wetzel, Richter, & Fort, 2010, p. -

Metamodernism and Vaporwave: a Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 14 | Issue 1 Article 3 Metamodernism and Vaporwave: A Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture Nicholas Morrissey University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh Recommended Citation Morrissey, Nicholas. “Metamodernism and Vaporwave: A Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture.” Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology 14, no. 1 (2021): 64-82. https://doi.org/10.5206/notabene.v14i1.13361. Metamodernism and Vaporwave: A Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture Abstract With the advent of Web 2.0, new forms of cultural and aesthetic texts, including memes and user generated content (UGC), have become increasingly popular worldwide as streaming and social media services have become more ubiquitous. In order to acknowledge the relevance and importance of these texts in academia and art, this paper conducts a three-part analysis of Vaporwave—a unique multimedia style that originated within Web 2.0—through the lens of a new cultural philosophy known as metamodernism. Relying upon a breadth of cultural theory and first-hand observations, this paper questions the extent to which Vaporwave is interested in metamodernist constructs and asks whether or not the genre can be classed as a metamodernist text, noting the dichotomy and extrapolation of nostalgia promoted by the genre and the unique instrumentality it offers to its consumers both visually and sonically. This paper ultimately theorizes that online culture will continue to play an important role in cultural production, aesthetic mediation, and even -

The Social Significance of Modern Trademarks: Authorizing the Appropriation of Marks As Source Identifiers for Expressive Works*

YAQUINTO.TOPRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 2/8/2017 11:25 AM The Social Significance of Modern Trademarks: Authorizing the Appropriation of Marks as Source Identifiers for * Expressive Works Dieuson Octave is a nineteen-year-old rapper from Florida that recently signed a deal with Atlantic Records. His YouTube videos have millions of views. He releases his music under the name Kodak Black. Some graffiti writers use stickers in addition to spray paint. In San Francisco, a writer named Ther had stickers appropriating the The North Face logo. Instead of reading The North Face in stacked type, Ther’s stickers read “Ther Norco Face.” Norco is a brand of prescription painkiller. Vaporwave is an obscure genre of music. Largely sample-based, it is characterized by an obsession with retro aesthetics, new technology, and consumerism. Songs range from upbeat to hypnogogic. They sometimes incorporate sound marks. Vaporwave musicians have monikers like Saint Pepsi and Macintosh Plus. Gucci Mane is a rap star and actor from Atlanta. All nine of his studio albums have placed on the Billboard Top 200. In 2013, he starred alongside James Franco and Selena Gomez in Spring Breakers, which competed for the Golden Lion award at the sixty-ninth Venice International Film Festival. Stuart Helm is an artist who formerly used the moniker King VelVeeda. Until the early 2000s, he operated cheeseygraphics.com, a website that sold his bawdy-themed art and advertised commercial art services. Horst Simco is a recording artist from Houston who goes by Riff Raff. His collection of tattoos includes the NBA logo, the MTV logo, and the BET logo. -

Music That Laughs 2017

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Adam Harper Music that laughs 2017 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1817 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Harper, Adam: Music that laughs. In: POP. Kultur und Kritik, Jg. 6 (2017), Nr. 1, S. 60– 65. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1817. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:101:1-2020052211120328716628 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

University of Birmingham from Microsound to Vaporwave

University of Birmingham From Microsound to Vaporwave Born, Georgina; Haworth, Christopher DOI: 10.1093/ml/gcx095 Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Born, G & Haworth, C 2018, 'From Microsound to Vaporwave: internet-mediated musics, online methods, and genre', Music and Letters, vol. 98, no. 4, pp. 601–647. https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcx095 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility: 30/03/2017 This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Music and Letters following peer review. The version of record Georgina Born, Christopher Haworth; From Microsound to Vaporwave: Internet-Mediated Musics, Online Methods, and Genre, Music and Letters, Volume 98, Issue 4, 1 November 2017, Pages 601–647 is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcx095 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

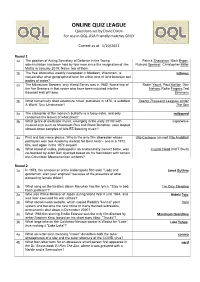

ONLINE QUIZ LEAGUE Questions Set by David Dixon for Use in OQL-USA Friendly Matches ONLY

ONLINE QUIZ LEAGUE Questions set by David Dixon For use in OQL-USA Friendly matches ONLY Correct as at 1/10/2021 Round 1 1a The position of Acting Secretary of Defense in the Trump Patrick Shanahan, Mark Esper, administration has been held by four men since the resignation of Jim Richard Spencer, Christopher Miller Mattis in January 2019. Name two of them 1b The free alternative weekly newspaper in Madison, Wisconsin, is Isthmus named after what geographical term for a thin strip of land between two bodies of water? 2a The Milwaukee Brewers' only World Series was in 1982. Name two of Robin Yount, Paul Molitor, Don the five Brewers in that roster who have been inducted into the Nelson, Rollie Fingers,Ted Baseball Hall of Fame. Simmons 2b What numerically titled adventure novel, published in 1870, is subtitled Twenty Thousand Leagues Under A World Tour Underwater? The Sea 3a The caterpillar of the monarch butterfly is a fussy eater, and only milkweed consumes the leaves of what plant? 3b What genre of electronic music, emerging in the early 2010s with vaporwave musical acts such as Macintosh Plus and Blank Banshee, uses looped, slowed-down samples of 80s EZ-listening music? 4a First and last name please. Who is the only film character whose Vito Corleone (accept Vito Andolini) portrayals won two Academy Awards for Best Actor-- one in a 1972 film, and again in the 1974 sequel? 4b What brand of vodka, packaged in an anatomically-correct bottle, was Crystal Head (NOT Skull) co-founded by actor Dan Aykroyd based on his fascination with certain -

The Music (And More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report

The Music (and More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report Report covers the time period of July 1st to Kieran Robbins & Chief - "Sway" [glam rock] September 30th, 2019. I inadvertently missed Troy a few before that time period, which were brought to my attention by fans, bands & Moriah Formica - "I Don't Care What You others. The missing are listed at the end, along with an Think" (single) [hard rock] Albany End Note… Nine Votes Short - "NVS: 09/03/2019" [punk rock] RECORDINGS: Albany Hard Rock / Metal / Punk Psychomanteum - "Mortal Extremis" (single track) Attica - "Resurected" (EP) [hardcore metal] Albany [thrash prog metal industrial] Albany Between Now and Forever - "Happy" (single - Silversyde - "In The Dark" [christian gospel hard rock] Mudvayne cover) [melodic metal rock] Albany Troy/Toledo OH Black Electric - "Black Electric" [heavy stoner blues rock] Scotchka - "Back on the Liquor" | "Save" (single tracks) Voorheesville [emo pop punk] Albany Blood Blood Blood - "Stranglers” (single) [darkwave Somewhere To Call Home - "Somewhere To Call Home" horror synthpunk] Troy [nu-metalcore] Albany Broken Field Runner – "Lay My Head Down" [emo pop Untaymed - "Lady" (single track) [british hard rock] punk] Albany / LA Colonie Brookline - "Live From the Bunker - Acoustic" (EP) We’re History - "We’re History" | "Pop Tarts" - [acoustic pop-punk alt rock] Greenwich "Avalanche" (singles) [punk rock pop] Saratoga Springs Candy Ambulance - "Traumantic" [alternative grunge Wet Specimens - "Haunted Flesh" (EP) [hardcore punk] rock] Saratoga Springs Albany Craig Relyea - "Between the Rain" (single track) Rock / Pop [modern post-rock] Schenectady Achille - "Superman (A Song for Mora)" (single) [alternative pop rock] Albany Dead-Lift - "Take It or Leave It" (single) [metal hard rock fusion] Schenectady Caramel Snow - "Wheels Are Meant To Roll Away" (single track) [shoegaze dreampop] Delmar Deep Slut - "u up?" (3-song) [punk slutcore rap] Albany Cassandra Kubinski - "DREAMS (feat. -

Genre in Practice: Categories, Metadata and Music-Making in Psytrance Culture

Genre in Practice: Categories, Metadata and Music-Making in Psytrance Culture Feature Article Christopher Charles University of Bristol (UK) Abstract Digital technology has changed the way in which genre terms are used in today’s musical cultures. Web 2.0 services have given musicians greater control over how their music is categorised than in previous eras, and the tagging systems they contain have created a non-hierarchical environment in which musical genres, descriptive terms, and a wide range of other metadata can be deployed in combination, allowing musicians to describe their musical output with greater subtlety than before. This article looks at these changes in the context of psyculture, an international EDM culture characterised by a wide vocabulary of stylistic terms, highlighting the significance of these changes for modern-day music careers. Profiles are given of two artists, and their use of genre on social media platforms is outlined. The article focuses on two genres which have thus far been peripheral to the literature on psyculture, forest psytrance and psydub. It also touches on related genres and some novel concepts employed by participants (”morning forest” and ”tundra”). Keywords: psyculture; genre; internet; forest psytrance; psydub Christopher Charles is a musician and researcher from Bristol, UK. His recent PhD thesis (2019) looked at the careers of psychedelic musicians in Bristol with chapters on event promotion, digital music distribution, and online learning. He produces and performs psydub music under the name Geoglyph, and forest psytrance under the name Espertine. Email: <[email protected]>. Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 12(1): 22–47 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2020 Dancecult http://dj.dancecult.net http://dx.doi.org/10.12801/1947-5403.2020.12.01.09 Charles | Genre in Practice: Categories, Metadata and Music-Making in Psytrance Culture 23 Introduction The internet has brought about important changes to the nature and function of genre in today’s musical cultures. -

Do You Want Vaporwave, Or Do You Want the Truth?

2017 | Capacious: Journal for Emerging Affect Inquiry 1 (1) CAPACIOUS Do You Want Vaporwave, or Do You Want the Truth? Cognitive Mapping of Late Capitalist Affect in the Virtual Lifeworld of Vaporwave Alican Koc UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO In "Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism," Frederic Jameson (1991) mentions an “aesthetic of cognitive mapping” as a new form of radical aesthetic practice to deal with the set of historical situations and problems symp- tomatic of late capitalism. For Jameson (1991), cognitive mapping functions as a tool for postmodern subjects to represent the totality of the global late capitalist system, allowing them to situate themselves within the system, and to reenact the critique of capitalism that has been neutralized by postmodernist confusion. Drawing upon a close reading of the music and visual art of the nostalgic in- ternet-based “vaporwave” aesthetic alongside Jameson’s postmodern theory and the afect theory of Raymond Williams (1977) and Brian Massumi (1995; 1998), this essay argues that vaporwave can be understood as an attempt to aestheticize and thereby map out the afective climate circulating in late capitalist consumer culture. More specifcally, this paper argues that through its somewhat obsessive hypersaturation with retro commodities and aesthetics from the 1980s and 1990s, vaporwave simultaneously critiques the salient characteristics of late capitalism such as pastiche, depthlessness, and waning of afect, and enacts a nostalgic long- ing for a modernism that is feeing further and further into an inaccessible history. KEYWORDS Afect, Postmodernism, Late Capitalism, Cognitive Mapping, Aesthetics Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0) capaciousjournal.com | DOI: https://doi.org/10.22387/cap2016.4 58 Do You Want Vaporwave, or Do You Want the Truth? Purgatory A widely shared image on the Internet asks viewers to refect on the atrocities of the past century. -

Microgenres MOUG 2021 Presentation (6.531Mb)

Microgenres Memory, Community, and Preserving the Present Leonard Martin Resource Description Librarian Metadata and Digitization Services University of Houston Brief Overview • Microgenres as a cultural phenomenon. • Metadata description for musical microgenres in a library environment using controlled vocabularies and resources. • Challenges and resources for identifying and acquiring microgenre musical sound recordings. • This presentation will focus on chopped and screwed music, vaporwave music, and ambient music. Microgenre noun /mi ∙ cro ∙ gen ∙ re/ 1. A hyper-specific subcategory of artistic, musical, or literary composition characterized that is by a particular style, form, or content. 2. A flexible, provisional, and temporary category used to establish micro- connections among cultural artifacts, drawn from a range of historical periods found in literature, film, music, television, and the performing and fine arts. 3. A specialized or niche genre; either machine-classified or retroactively established through analysis. Examples of Musical Microgenres Hyper-specific • Chopped and screwed music Flexible, provisional, and temporary • Vaporwave music Specialized or niche • Ambient music Ambient Music • Ambient music is a broad microgenre encompassing a breath of natural sounds, acoustic and electronic instruments, and utilizes sampling and/or looping material Discreet Music, Discreet Music, by Brian Eno, 1975, EG Records. to generate repetitive soundscapes. • Earlier works from Erik Satie’s musique d’ameublement (furniture music) to the musique concrete works of Éliane Radigue, Steve Reich’s tape pieces, and synthesizer albums of Wendy Carlos are all precursors of ambient music. • The term ambient music was coined by composer Brian Eno upon the release of Michigan Turquoise, Catch a Blessing. 2019. Genre tags: devotional, ambient, his album, “Discreet Music,” in 1975. -

HUMAN EXCESS Aesthetics of Post-Internet Electronic Music

HUMAN EXCESS Aesthetics Of Post-Internet Electronic Music Anders Bach Pedersen IT-University, Copenhagen [email protected] ABSTRACT session in musical commentary.” [1] For Ferraro, a para- doxical aporia appears in the juxtaposition of hyperreal There exists a tenacious dichotomy between the ‘organic’ iterations of aliveness and lifelessness; organicness and and the ‘synthetic’ in electronic music. In spite of imme- the synthetic. It is the feeling of otherness and unity, ma- diate opposing qualities, they instill sensations of each nyness and oneness [4], that gives rise to an aesthetic other in practice: Acoustic sounds are subject to artificial commentary on the political economy of music because mimicry while algorithmic music can present an imitation of the associations the sounds of “neotenous plastics” [1] of human creativity. This presents a post-human aesthetic invoke. This paper discusses how some contemporary that questions if there are echoes of life in the machine. experimental electronic musics post-2010 seem to be This paper investigates how sonic aesthetics in the bor- moving towards the hyperreal – “[…] the generation by derlands between electronic avant-garde, pop and club models of a real without origin or reality” [5] – in both music have changed after 2010. I approach these aesthet- sonic materiality and cultural reference. From the 90’s ics through Brian Massumi’s notions of ‘semblance’ and IDM-moniker name change to Internet Dance Music [6] ‘animateness’ as abstract monikers to assist in the trac- and its offspring known as Electronic Dance Music ing of meta-aesthetic experiences of machine-life, genre, (EDM) turned commodity by the US music industry as a musical structure and the listening to known-unknown re-brand of the rave culture [7] to the recent ‘resurgence’ noise.