Metamodernism and Vaporwave: a Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Queer Expressions in Mens Underwear Through Post Internet Aesthetic As Vaporwave

Mens underwear :Exploring queer expressions in mens underwear through post internet aesthetic as Vaporwave. Master in fashion design Mario Eurenius 2018.6.09. 1. Abstract This work explores norms of dress design by the use of post internet aesthetics in mens underwear. The exploration of underwear is based on methods formed to create a wider concept of how mens underwear could look like regarding shape, color, material and details. Explorations of stereotypical and significant elements of underwear such as graphics and logotypes has been reworked to create a graphical identity bound to a brand. This is made to contextualize the work aiming to present new options and variety in mens underwear rather than stating examples using symbols or stereotypic elements. In the making of the examples for this work the process goes front and back from digital to physical using different media to create compositions of color, graphic designs and outlines using transfer printer, digital print, and laser cutting machine. Key words: Mens underwear, graphic, colour, norm, identity, post internet, laser cut. P: P: 2 Introduction to the field 3 Method 15 What is underwear? 39 Shape, Rough draping Historical perspective 17 Male underwear and nudity 41 From un-dressed to dressed 18 Graphics in fashion and textiles 42 Illustrator sketching 19 Differencesin type and categories of mensunderwear 43 shape grapich design 2,1 Background 3.1 Developement 45 collection of pictures 49 Colour 20 Vaporwave 50 Rough draping Japanese culture 21 Mucis 55 Rough draping 2 22 -

Metamodernism, Or Exploring the Afterlife of Postmodernism

“We’re Lost Without Connection”: Metamodernism, or Exploring the Afterlife of Postmodernism MA Thesis Faculty of Humanities Media Studies MA Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Giada Camerra S2103540 Media Studies: Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Leiden, 14-06-2020 Supervisor: Dr. M.J.A. Kasten Second reader: Dr.Y. Horsman Master thesis submitted in accordance with the regulations of Leiden University 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 1: Discussing postmodernism ........................................................................................ 10 1.1 Postmodernism: theories, receptions and the crisis of representation ......................................... 10 1.2 Postmodernism: introduction to the crisis of representation ....................................................... 12 1.3 Postmodern aesthetics ................................................................................................................. 14 1.3.1 Sociocultural and economical premise ................................................................................. 14 1.3.2 Time, space and meaning ..................................................................................................... 15 1.3.3 Pastiche, parody and nostalgia ............................................................................................ -

RE-ANIMATING GHOSTS MATERIALITY and MEMORY in HAUNTOLOGICAL APPROPRIATION Abstract

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF FILM AND MEDIA ARTS (2019) Vol. 4, Nº. 2 pp. 24-37 © 2019 BY-NC-ND ijfma.ulusofona.pt DOI: 10.24140/ijfma.v4.n2.02 RE-ANIMATING GHOSTS MATERIALITY AND MEMORY IN HAUNTOLOGICAL APPROPRIATION Abstract This research examines the spectrality of an- MICHAEL PETER SCHOFIELD imation and other media based on the photo- graphic trace. Using diverse examples from pop- ular culture and the author’s own investigative practice in media art, this paper looks at how ar- chival media is re-used and can be brought back to life in new moving image works, in a gesture we might call hauntological appropriation. While sampling and re-using old materials is nothing new, over the last 15 years we have seen an ongoing tendency to foreground the ghostly qualities of vintage recordings and found foot- age, and a recurrent fetishisation and simula- tion of obsolete technologies. Here we examine the philosophies and productions behind this hauntological turn and why the materiality of still and moving image media has become such a focus. We ask how that materiality effects the machines that remember for us, and how we re- use these analogue memories in digital cultures. Due to the multimodal nature of the author’s creative practice, photography, video art, doc- umentary film and animation, are interrogated here theoretically. Re-animating the ghosts of old media can reveal ontological differences between these forms, and a ghostly synergy be- tween the animated and the photographic. Keywords: hauntology, animation, memory, media * University of Leeds, United Kingdom archaeology, appropriation, ontology, animated [email protected] documentary 24 RE-ANIMATING GHOSTS MICHAEL PETER SCHOFIELD Every culture has its phantoms and the spectral- how we can foreground their specific materiality, and the ity that is conditioned by its technology (Derrida, haunting associations with personal and cultural memory Amelunxen, Wetzel, Richter, & Fort, 2010, p. -

Transmodern Reconfigurations of Territoriality

societies Article Transmodern Reconfigurations of Territoriality, Defense, and Cultural Awareness in Ken MacLeod’s Cosmonaut Keep Jessica Aliaga-Lavrijsen Centro Universitario de la Defensa Zaragoza, Zaragoza 50090, Spain; [email protected] Received: 5 September 2018; Accepted: 17 October 2018; Published: 19 October 2018 Abstract: This paper focuses on the science fiction (SF) novel Cosmonaut Keep (2000)—first in the trilogy Engines of Light, which also includes Dark Light (2001) and Engines of Light (2002)—by the Scottish writer Ken MacLeod, and analyzes from a transmodern perspective some future warfare aspects related to forthcoming technological development, possible reconfigurations of territoriality in an expanding cluster of civilizations travelling and trading across distant solar systems, expanded cultural awareness, and space ecoconsciousness. It is my argument that MacLeod’s novel brings Transmodernism, which is characterized by a “planetary vision” in which human beings sense that we are interdependent, vulnerable, and responsible, into the future. Hereby, MacLeod’s work expands the original conceptualization of the term “Transmodernism” as defined by Rodríguez Magda, and explores possible future outcomes, showing a unique awareness of the fact that technological processes are always linked to political and power-related uses. Keywords: cultural awareness; future warfare; globalization; Fifth-Generation War; intergalactic territoriality; planetary civilizations; SF; space ecoconsciousness; speculative fiction; technological development; transmodernism “Where there is no vision, the people perish.” —Proverbs 29:18 “If these are the early days of a better nation there must be hope, and a hope of peace is as good as any, and far better than a hollow hoarding greed or the dry lies of an aweless god.” —Graydon Saunders 1. -

ASIB 110 Winter 2014 LETTER

M E R I C A T U D I E S R I T A I N NO. 110 WINTER 2014 ISSN 1465-9956 N ASINB BAAS.AC.UK 6 0 Special Anniversary Issue EDITOR’S ASIB 110 Winter 2014 LETTER ‘Neurolysis’ and Wilka Hudson ext year is the 60th anniversary of BAAS. To mark the address as Chair of the Association is reprinted from occasion, this special issue of ASIB pays homage to page 4. (Sue reviewed many of the recent activities Nsome of the beautiful architecture of next year’s and achievements across the community at the 59th conference host city, Newcastle-upon-Tyne. The BAAS conference in Birmingham organised by Sara image above is a wide-angle shot of the Newcastle Wood.) This issue of ASIB also includes a piece by Quayside. The cover shows the Sage Gateshead and Hannah Murray (p. 11) on the transatlantic legacy of Tyne Bridge at dusk. More details about the the civil rights activist and author Frederick Douglass. conference, including the website and Twitter handle Finally, postgraduate students in the community are supplied by Northumbria University, can be found on encouraged to get in touch with the BAAS PG the next page. A preliminary programme is expected representative, Rachael Alexander (p. 12). in March on baas.ac.uk. I hope you enjoy this issue of ASIB. As ever, this issue of ASIB is brimming with report writing by the Association’s travel/research Warm regards, award recipients. There is certainly enough to ignite any Americanist’s wanderlust, with articles (starting p. -

The Social Significance of Modern Trademarks: Authorizing the Appropriation of Marks As Source Identifiers for Expressive Works*

YAQUINTO.TOPRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 2/8/2017 11:25 AM The Social Significance of Modern Trademarks: Authorizing the Appropriation of Marks as Source Identifiers for * Expressive Works Dieuson Octave is a nineteen-year-old rapper from Florida that recently signed a deal with Atlantic Records. His YouTube videos have millions of views. He releases his music under the name Kodak Black. Some graffiti writers use stickers in addition to spray paint. In San Francisco, a writer named Ther had stickers appropriating the The North Face logo. Instead of reading The North Face in stacked type, Ther’s stickers read “Ther Norco Face.” Norco is a brand of prescription painkiller. Vaporwave is an obscure genre of music. Largely sample-based, it is characterized by an obsession with retro aesthetics, new technology, and consumerism. Songs range from upbeat to hypnogogic. They sometimes incorporate sound marks. Vaporwave musicians have monikers like Saint Pepsi and Macintosh Plus. Gucci Mane is a rap star and actor from Atlanta. All nine of his studio albums have placed on the Billboard Top 200. In 2013, he starred alongside James Franco and Selena Gomez in Spring Breakers, which competed for the Golden Lion award at the sixty-ninth Venice International Film Festival. Stuart Helm is an artist who formerly used the moniker King VelVeeda. Until the early 2000s, he operated cheeseygraphics.com, a website that sold his bawdy-themed art and advertised commercial art services. Horst Simco is a recording artist from Houston who goes by Riff Raff. His collection of tattoos includes the NBA logo, the MTV logo, and the BET logo. -

Hungry for Art

Hungry for Art A semiotic reading of food signifying art in the episode Grant Achatz (2016) in the documentary Chef’s Table (2015-present) Dana van Ooijen, s4243870 June 2017 Bachelor’s Thesis Algemene Cultuurwetenschappen (Arts and Culture Studies) Faculty of Humanities Supervisor: Dr. J.A. Naeff Radboud University, Nijmegen Second Reader: 1 Table of Contents Abstract: Hungry for Art ..................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 1. Plating like Pollock (and other Abstract Expressionists) ............................................... 8 Peirce and Intertextuality ..................................................................................................................... 8 Abstract Expressionists (Jackson Pollock) ........................................................................................ 10 Two Types of Intertextual Relations ............................................................................................. 11 Chapter 2. Moving like the Modernists ............................................................................................. 15 Peirce and Modernism ....................................................................................................................... 15 Modernism Applied .......................................................................................................................... -

Metamodernism and New Romanticism

Metamodernism & New Romanticism The world must be romanticized. In this way its original meaning will be rediscovered. To romanticize is nothing but a qualitative heightening. In this process the lower self becomes identified with a better self. (…) Insofar as I present the commonplace with significance, the ordinary with mystery, the familiar with the seemliness of the unfamiliar and the finite with the semblance of the infinite, I romanticize it1. These words by Novalis have long been suppressed by the modern paradigm and ignored by postmodern discourses. However, over the last two decades or so, they have gradually begun to re-emerge. In 2005 they were reprinted in Max Hollein’s catalogue Ideal world: New Romanticism in Contemporary Art2. They were expressed with such conviction, there could be no more doubt about it: a new sense of the Romantic has emerged3. Our society is marked by increasing mobility and the waning of social bonds. As a response, a new yearning for intimacy and security seems to prevail. As a result we are now confronted with a revival of the traditional work wherever we turn to4. It can be seen in the re-appraisal of Bas Jan Ader’s questioning of Reason, in the attention for Peter Doig’s re- appropriation of culture through nature and it can be perceived in Olafur Eliasson’s obsession with the commonplace5. It can also be observed in David Thorpe’s fascination with the 30 fictitious or in Charles Avery’s interest for fictional elsewheres6. Many contemporary artists seem to have taken up the Romantic spirit. -

Music That Laughs 2017

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Adam Harper Music that laughs 2017 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1817 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Harper, Adam: Music that laughs. In: POP. Kultur und Kritik, Jg. 6 (2017), Nr. 1, S. 60– 65. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1817. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:101:1-2020052211120328716628 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

University of Birmingham from Microsound to Vaporwave

University of Birmingham From Microsound to Vaporwave Born, Georgina; Haworth, Christopher DOI: 10.1093/ml/gcx095 Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Born, G & Haworth, C 2018, 'From Microsound to Vaporwave: internet-mediated musics, online methods, and genre', Music and Letters, vol. 98, no. 4, pp. 601–647. https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcx095 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility: 30/03/2017 This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Music and Letters following peer review. The version of record Georgina Born, Christopher Haworth; From Microsound to Vaporwave: Internet-Mediated Musics, Online Methods, and Genre, Music and Letters, Volume 98, Issue 4, 1 November 2017, Pages 601–647 is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcx095 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

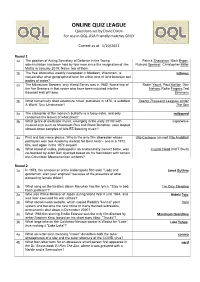

ONLINE QUIZ LEAGUE Questions Set by David Dixon for Use in OQL-USA Friendly Matches ONLY

ONLINE QUIZ LEAGUE Questions set by David Dixon For use in OQL-USA Friendly matches ONLY Correct as at 1/10/2021 Round 1 1a The position of Acting Secretary of Defense in the Trump Patrick Shanahan, Mark Esper, administration has been held by four men since the resignation of Jim Richard Spencer, Christopher Miller Mattis in January 2019. Name two of them 1b The free alternative weekly newspaper in Madison, Wisconsin, is Isthmus named after what geographical term for a thin strip of land between two bodies of water? 2a The Milwaukee Brewers' only World Series was in 1982. Name two of Robin Yount, Paul Molitor, Don the five Brewers in that roster who have been inducted into the Nelson, Rollie Fingers,Ted Baseball Hall of Fame. Simmons 2b What numerically titled adventure novel, published in 1870, is subtitled Twenty Thousand Leagues Under A World Tour Underwater? The Sea 3a The caterpillar of the monarch butterfly is a fussy eater, and only milkweed consumes the leaves of what plant? 3b What genre of electronic music, emerging in the early 2010s with vaporwave musical acts such as Macintosh Plus and Blank Banshee, uses looped, slowed-down samples of 80s EZ-listening music? 4a First and last name please. Who is the only film character whose Vito Corleone (accept Vito Andolini) portrayals won two Academy Awards for Best Actor-- one in a 1972 film, and again in the 1974 sequel? 4b What brand of vodka, packaged in an anatomically-correct bottle, was Crystal Head (NOT Skull) co-founded by actor Dan Aykroyd based on his fascination with certain -

The Music (And More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report

The Music (and More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report Report covers the time period of July 1st to Kieran Robbins & Chief - "Sway" [glam rock] September 30th, 2019. I inadvertently missed Troy a few before that time period, which were brought to my attention by fans, bands & Moriah Formica - "I Don't Care What You others. The missing are listed at the end, along with an Think" (single) [hard rock] Albany End Note… Nine Votes Short - "NVS: 09/03/2019" [punk rock] RECORDINGS: Albany Hard Rock / Metal / Punk Psychomanteum - "Mortal Extremis" (single track) Attica - "Resurected" (EP) [hardcore metal] Albany [thrash prog metal industrial] Albany Between Now and Forever - "Happy" (single - Silversyde - "In The Dark" [christian gospel hard rock] Mudvayne cover) [melodic metal rock] Albany Troy/Toledo OH Black Electric - "Black Electric" [heavy stoner blues rock] Scotchka - "Back on the Liquor" | "Save" (single tracks) Voorheesville [emo pop punk] Albany Blood Blood Blood - "Stranglers” (single) [darkwave Somewhere To Call Home - "Somewhere To Call Home" horror synthpunk] Troy [nu-metalcore] Albany Broken Field Runner – "Lay My Head Down" [emo pop Untaymed - "Lady" (single track) [british hard rock] punk] Albany / LA Colonie Brookline - "Live From the Bunker - Acoustic" (EP) We’re History - "We’re History" | "Pop Tarts" - [acoustic pop-punk alt rock] Greenwich "Avalanche" (singles) [punk rock pop] Saratoga Springs Candy Ambulance - "Traumantic" [alternative grunge Wet Specimens - "Haunted Flesh" (EP) [hardcore punk] rock] Saratoga Springs Albany Craig Relyea - "Between the Rain" (single track) Rock / Pop [modern post-rock] Schenectady Achille - "Superman (A Song for Mora)" (single) [alternative pop rock] Albany Dead-Lift - "Take It or Leave It" (single) [metal hard rock fusion] Schenectady Caramel Snow - "Wheels Are Meant To Roll Away" (single track) [shoegaze dreampop] Delmar Deep Slut - "u up?" (3-song) [punk slutcore rap] Albany Cassandra Kubinski - "DREAMS (feat.