No List of Political Assets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Representations of the Holocaust in Soviet cinema Timoshkina, Alisa Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 REPRESENTATIONS OF THE HOLOCAUST IN SOVIET CINEMA Alissa Timoshkina PhD in Film Studies 1 ABSTRACT The aim of my doctoral project is to study how the Holocaust has been represented in Soviet cinema from the 1930s to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. -

The Bolshoi Meets Bolshevism: Moving Bodies and Body Politics, 1917-1934

THE BOLSHOI MEETS BOLSHEVISM: MOVING BODIES AND BODY POLITICS, 1917-1934 By Douglas M. Priest A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History – Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT THE BOLSHOI MEETS BOLSHEVISM: MOVING BODIES AND BODY POLITICS, 1917- 1934 By Douglas M. Priest Following the Russian Revolution in 1917, the historically aristocratic Bolshoi Ballet came face to face with Bolshevik politics for the first time. Examining the collision of this institution and its art with socialist politics through the analysis of archival documents, published material, and ballets themselves, this dissertation explains ballet’s persisting allure and cultural power in the early Soviet Union. The resulting negotiation of aesthetic and political values that played out in a discourse of and about bodies on the Bolshoi Theater’s stage and inside the studios of the Bolshoi’s Ballet School reveals Bolshevik uncertainty about the role of high culture in their new society and helped to define the contentious relationship between old and new in the 1920s. Furthermore, the most hostile attack on ballet coming from socialists, anti- formalism, paradoxically provided a rhetorical shield for classical ballet by silencing formalist critiques. Thus, the collision resulted not in one side “winning,” but rather in a contested environment in which dancers embodied both tradition and revolution. Finally, the persistence of classical ballet in the 1920s, particularly at the Ballet School, allowed for the Bolshoi Ballet’s eventual ascendancy to world-renowned ballet company following the second World War. This work illuminates the Bolshoi Ballet’s artistic work from 1917 to 1934, its place and importance in the context of early Soviet culture, and the art form’s cultural power in the Soviet Union. -

Soviet Cinema

Soviet Cinema: Film Periodicals, 1918-1942 Where to Order BRILL AND P.O. Box 9000 2300 PA Leiden The Netherlands RUSSIA T +31 (0)71-53 53 500 F +31 (0)71-53 17 532 BRILL IN 153 Milk Street, Sixth Floor Boston, MA 02109 USA T 1-617-263-2323 CULTURE F 1-617-263-2324 For pricing information, please contact [email protected] MASS www.brill.nl www.idc.nl “SOVIET CINemA: Film Periodicals, 1918-1942” collections of unique material about various continues the new IDC series Mass Culture and forms of popular culture and entertainment ENTERTAINMENT Entertainment in Russia. This series comprises industry in Tsarist and Soviet Russia. The IDC series Mass Culture & Entertainment in Russia The IDC series Mass Culture & Entertainment diachronic dimension. It includes the highly in Russia comprises collections of extremely successful collection Gazety-Kopeiki, as well rare, and often unique, materials that as lifestyle magazines and children’s journals offer a stunning insight into the dynamics from various periods. The fifth sub-series of cultural and daily life in Imperial and – “Everyday Life” – focuses on the hardship Soviet Russia. The series is organized along of life under Stalin and his somewhat more six thematic lines that together cover the liberal successors. Finally, the sixth – “High full spectrum of nineteenth- and twentieth Culture/Art” – provides an exhaustive century Russian culture, ranging from the overview of the historic avant-garde in Russia, penny press and high-brow art journals Ukraine, and Central Europe, which despite in pre-Revolutionary Russia, to children’s its elitist nature pretended to cater to a mass magazines and publications on constructivist audience. -

1. Coversheet Thesis

Eleanor Rees The Kino-Khudozhnik and the Material Environment in Early Russian and Soviet Fiction Cinema, c. 1907-1930. January 2020 Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Slavonic and East European Studies University College London Supervisors: Dr. Rachel Morley and Dr. Philip Cavendish !1 I, Eleanor Rees confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Word Count: 94,990 (including footnotes and references, but excluding contents, abstract, impact statement, acknowledgements, filmography and bibliography). ELEANOR REES 2 Contents Abstract 5 Impact Statement 6 Acknowledgments 8 Note on Transliteration and Translation 10 List of Illustrations 11 Introduction 17 I. Aims II. Literature Review III. Approach and Scope IV. Thesis Structure Chapter One: Early Russian and Soviet Kino-khudozhniki: 35 Professional Backgrounds and Working Practices I. The Artistic Training and Pre-cinema Affiliations of Kino-khudozhniki II. Kino-khudozhniki and the Russian and Soviet Studio System III. Collaborative Relationships IV. Roles and Responsibilities Chapter Two: The Rural Environment 74 I. Authenticity, the Russian Landscape and the Search for a Native Cinema II. Ethnographic and Psychological Realism III. Transforming the Rural Environment: The Enchantment of Infrastructure and Technology in Early-Soviet Fiction Films IV. Conclusion Chapter Three: The Domestic Interior 114 I. The House as Entrapment: The Domestic Interiors of Boris Mikhin and Evgenii Bauer II. The House as Ornament: Excess and Visual Expressivity III. The House as Shelter: Representations of Material and Psychological Comfort in 1920s Soviet Cinema IV. -

Traces the UNC-Chapel Hill Journal of History

traces The UNC-Chapel Hill Journal of History volume 3 spring 2014 The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Published in the United States of America by the UNC-Chapel Hill History Department traces Hamilton Hall, CB #3195 Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3195 (919) 962-2115 [email protected] Copyright 2014 by UNC-Chapel Hill All rights reserved. Except in those cases that comply with the fair use guidelines of US copyright law (U.S.C. Title 17), no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. Design by Brandon Whitesell. Printed in the United States of America by Chamblee Graphics, Raleigh, North Carolina. Traces is produced by undergraduate and graduate students at UNC-Chapel Hill in order to showcase students’ historical research. Traces: The UNC-Chapel Hill Journal of History is affiliated with the Delta Pi chapter (UNC-Chapel Hill) of Phi Alpha Theta, the National History Honor Society. Unfortunately there is no Past, available for distillation, capture, manipulation, observation and description. There have been, and there are, events in complex and innumerable combinations, and no magic formula “will ever give us masterytraces over them . There are, instead, some rather humdrum operations to be performed. We suspect or surmise that an event, a set of events has taken place: where can we find the traces they must have left behind them? Or we have come across some traces: what are they worth, as traces, and to what events do they point? Later on we shall find out which events we can, from our own knowledge of their traces, safely believe to have taken place. -

Contributors Auteurs

CONTRIBUTORS AUTEURS ELENA V. BARABAN is Associate Professor of Russian and co-ordinator of the Central and East European Studies Programme at the University of Manitoba. Dr. Baraban is an expert on Russian twentieth-century literature and popular culture. She is currently working on a monograph about representations of World War II in Soviet films of the Stalin era. Her research is informed by theory of trauma, structuralism, and gender studies. Her recent publications include a co-edited volume Fighting Words and Images: Representing War Across the Disciplines (together with Stephan Jaeger and Adam Muller for University of Toronto Press, 2012) as well as a number of articles on Soviet and post-Soviet popular culture in Canadian Slavonic Papers/Revue canadienne des slavistes, Slavic and East European Studies Journal, Ab Imperio, Aspasia, and other journals. LARYSA BRIUKHOVETS'KA is a leading Ukrainian film critic and film historian. The editor-in-chief of the country’s only continuing cinema journal, Kino-teatr, she also teaches in the Department of Cultural Studies at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. She is the author and editor of numerous books on Ukrainian cinema, including, most recently, an edited collection on Oleksandr Dovzhenko, Kinorezhyser svitovoi slavy (Logos, 2013) and a monograph on the film director Leonid Bykov, Svoie/ridne kino (Zadruha, 2010). VITALY CHERNETSKY is Associate Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Kansas. He is the author of the monograph Mapping Postcommunist Cultures: Russia and Ukraine in the Context of Globalization (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007) and of numerous articles and essays on Russian and Ukrainian literature and film, as well as translation studies. -

![A Severe Young Man [Строгий Юноша] USSR, 1936 Black-And-White, 97 Min Russian with English Subtitles Director: Abram](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6239/a-severe-young-man-ussr-1936-black-and-white-97-min-russian-with-english-subtitles-director-abram-2946239.webp)

A Severe Young Man [Строгий Юноша] USSR, 1936 Black-And-White, 97 Min Russian with English Subtitles Director: Abram

character is portrayed with what can only be regarded (at least today) a healthy dose of irony. The film was a true collaboration between the scriptwriter, Iurii Olesha, and the director Abram Room for whom the script was specifically written. Both men were extremely talented creative individuals who despite their seemingly earnest attempts could never quite find a comfortable fit between their works and the ideological demands of the times. Indeed, Room made A Severe Young Man in Ukraine not by choice, but because he was working in A Severe Young Man professional exile from Moscow as punishment [Строгий юноша ] for various “mistakes” made in his previous films. Room’s best work was often daringly USSR, 1936 provocative, and even those of his films that Black-and-white, 97 min received wide distribution were often vilified by Russian with English Subtitles the critics. Olesha, for his part, was a successful Director: Abram Room playwright and prose writer throughout the Script: Iurii Olesha 1920s, but his best works, while on the surface Cinematography: Iurii Ekel'chik ideologically correct, contained in their deeper Art Direction: Morits Umanskii and texture disturbingly discordant notes. His Vladimir Kaplunovskii literary output decreased after 1928 and, as a Composer: Gavriil Popov writer, he fell largely silent after 1934. The two Sound: Aleksandr Babii and Andrei men shared a common vision for A Severe Demidenko Young Man and the resulting film contributed to Cast: Iurii Iur'ev, Ol'ga Zhizneva, Dmitrii the shame of both in equal measure in 1936. Dorliak, Maksim Shtraukh, Valentina The film’s content makes no Serova, Georgii Sochevko, Irina Volodko concessions to the usual expectations of Soviet Production: Ukrainfil'm audiences of the 1930s. -

Viktor Shklovsky in the Film Factory

VIKTOR SHKLOVSKY IN THE FILM FACTORY Initially a participant in the Russian Futurist circle in St Petersburg which included David Burliuk, Vladimir Mayakovsky and Velimir Khlebnikov, Viktor Shklovsky became an important critic and theorist of art and literature in the 1910s and 1920s in Russia. In 1916 he founded OPOYAZ (Society for the Study of Poetic Language) with Yuri Tynianov, Osip Brik and Boris Eichenbaum. Up to its dissolution in the 1930s the group developed the innovative theories of literature characterised as Russian Formalism. Shklovsky participated in the Russian Revolution of February 1917 however immediately after the revolution of October 1917 he sided with the Socialist Revolutionaries against the Bolsheviks and was forced to hide in Ukraine, returning to participate in the Civil War, fleeing again in 1922 to Berlin where he stayed until 1923. In Berlin he published Knight’s Move, a collection of short essays and reviews written in a period spanning the first few years of the revolution, and Sentimental Journey, his memoir of the years of revolution and exile 1917-1922. Also, Shklovsky (then living in Berlin) published in 1923 a collection of his own essays and articles on film (Literature and Cinematography, first English edition 2008) as well as editing, with several of the Russian Formalist group, a collection on the work of Charlie Chaplin. Shklovsky’s novel, Zoo: Letters Not About Love, includes a letter appealing to the Soviet authorities to allow him to return. This, and the intercession of his literary peers, Maxim Gorky and Vladimir Mayakovsky, secured his return to Russia. However, in the context of Soviet Marxism’s suspicion of Shklovsky’s anti-Bolshevik past and the popularity of Formalism Shklovsky found fewer and fewer opportunities to publish in the 1920s, he instead sought employment in the State cinema of Goskino as a screenwriter, where he worked with the directors Lev Kuleshev, Abram Room, Boris Barnet and others. -

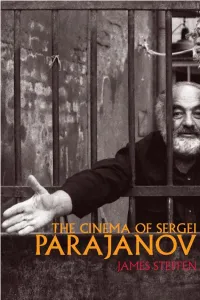

Cinema of Sergei Parajanov Parajanov Performs His Own Imprisonment for the Camera

The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov Parajanov performs his own imprisonment for the camera. Tbilisi, October 15, 1984. Courtesy of Yuri Mechitov. The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov James Steffen The University of Wisconsin Press Publication of this volume has been made possible, in part, through support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The University of Wisconsin Press 1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor Madison, Wisconsin 53711- 2059 uwpress.wisc .edu 3 Henrietta Street London WC2E 8LU, England eurospanbookstore .com Copyright © 2013 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Steffen, James. The cinema of Sergei Parajanov / James Steffen. p. cm. — (Wisconsin fi lm studies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 299- 29654- 4 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 299- 29653- 7 (e- book) 1. Paradzhanov, Sergei, 1924–1990—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Motion pictures—Soviet Union. I. Title. II. Series: Wisconsin fi lm studies. PN1998.3.P356S74 2013 791.430947—dc23 2013010422 For my family. Contents List of Illustrations ix -

Images in Prose and Film: Modernist Treatments of Gender

Images in Prose and Film: Modernist treatments of gender, education and early 20th century culture in Bryher’s Close Up essays, her volume Film Problems of Soviet Russia (1929), and her autobiographical fiction Zlatina Emilova Nikolova Royal Holloway, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) September 2018 1 Declaration of Authorship The title page should be followed by a signed declaration that the work presented in the thesis is the candidate’s own. Please note that there is no set wording for this but an example is provided below: Declaration of Authorship I …Zlatina Emilova Nikolova…………………. (please insert name) hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______________________ Date: ________________________ 2 This thesis explores the thematic and stylistic patterns across the previously unexplored fiction and non-fiction work of the modernist author Bryher. More precisely, this study focuses on Bryher's three autobiographical novels: Development (1920), Two Selves (1923) and West (1925), and the film criticism she published in the film journal Close Up (1927-1933) and her volume Film Problems of Soviet Russia (1929). Influenced by her experiences as a young woman at the turn of the twentieth century and World War I, Bryher formulated strong opinions on women's social status, education, and patriarchal society. These opinions and the style of prose that articulated these ideas in her novels translated into her film criticism and informed the author's understanding of the film medium and film art throughout the 1920s and 1930s. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Shklovsky in the Cinema, 1926-1932 BAKER, ROSEMARI,ELIZABETH How to cite: BAKER, ROSEMARI,ELIZABETH (2010) Shklovsky in the Cinema, 1926-1932, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/378/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Contents Contents 1 Illustrations 2 Statement of Copyright 4 Notes on Translation, Transliteration, and Dates 5 Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 7 Chapter 1: Criminal Law and the Pursuit of Justice 20 Courts Without Law 20 Legalised Lawlessness 29 Negotiating Responsibility 37 Improvised Justice 45 Chapter 2: Realistic Discontent and Utopian Desire 57 Justice as Social Daydream 57 God, the State, and Self 64 (Dys/U)topian Dreams of Rebellion 70 Active Deeds 70 Passive Fantasies 81 Chapter 3: Myths of Domestic Life and Social Responsibility 97 At Home in the City 97 Private House, Public Home 114 Chapter 4: Metatextual Modes of Judicial Expression 136 Self-Reflexive Performance and Genre Hybridity 136 Art Beyond Representation 153 Entertainment and/or Enlightenment 161 Intertextual and Intercultural Authorial Strategies 168 Conclusion 181 Bibliography 186 Filmography 208 1 Illustrations Fig. -

Download 2018–2019 Catalogue of New Plays

Catalogue of New Plays 2018–2019 © 2018 Dramatists Play Service, Inc. Dramatists Play Service, Inc. A Letter from the President Dear Subscriber: Take a look at the “New Plays” section of this year’s catalogue. You’ll find plays by former Pulitzer and Tony winners: JUNK, Ayad Akhtar’s fiercely intelligent look at Wall Street shenanigans; Bruce Norris’s 18th century satire THE LOW ROAD; John Patrick Shanley’s hilarious and profane comedy THE PORTUGUESE KID. You’ll find plays by veteran DPS playwrights: Eve Ensler’s devastating monologue about her real-life cancer diagnosis, IN THE BODY OF THE WORLD; Jeffrey Sweet’s KUNSTLER, his look at the radical ’60s lawyer William Kunstler; Beau Willimon’s contemporary Washington comedy THE PARISIAN WOMAN; UNTIL THE FLOOD, Dael Orlandersmith’s clear-eyed examination of the events in Ferguson, Missouri; RELATIVITY, Mark St. Germain’s play about a little-known event in the life of Einstein. But you’ll also find plays by very new playwrights, some of whom have never been published before: Jiréh Breon Holder’s TOO HEAVY FOR YOUR POCKET, set during the early years of the civil rights movement, shows the complexity of choosing to fight for one’s beliefs or protect one’s family; Chisa Hutchinson’s SOMEBODY’S DAUGHTER deals with the gendered differences and difficulties in coming of age as an Asian-American girl; Melinda Lopez’s MALA, a wry dramatic monologue from a woman with an aging parent; Caroline V. McGraw’s ULTIMATE BEAUTY BIBLE, about young women trying to navigate the urban jungle and their own self-worth while working in a billion-dollar industry founded on picking appearances apart.