Ready Set In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOW STEVE REEVES TRAINED by John Grimek

IRON GAME HISTORY VOL.5No.4&VOL. 6 No. 1 IRON GAME HISTORY ATRON SUBSCRIBERS THE JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL CULTURE P Gordon Anderson Jack Lano VOL. 5 NO. 4 & VOL. 6 NO. 1 Joe Assirati James Lorimer SPECIAL DOUBL E I SSUE John Balik Walt Marcyan Vic Boff Dr. Spencer Maxcy TABLE OF CONTENTS Bill Brewer Don McEachren Bill Clark David Mills 1. John Grimek—The Man . Terry Todd Robert Conciatori Piedmont Design 6. lmmortalizing Grimek. .David Chapman Bruce Conner Terry Robinson 10. My Friend: John C. Grimek. Vic Boff Bob Delmontique Ulf Salvin 12. Our Memories . Pudgy & Les Stockton 4. I Meet The Champ . Siegmund Klein Michael Dennis Jim Sanders 17. The King is Dead . .Alton Eliason Mike D’Angelo Frederick Schutz 19. Life With John. Angela Grimek Lucio Doncel Harry Schwartz 21. Remembering Grimek . .Clarence Bass Dave Draper In Memory of Chuck 26. Ironclad. .Joe Roark 32. l Thought He Was lmmortal. Jim Murray Eifel Antiques Sipes 33. My Thoughts and Reflections. .Ken Rosa Salvatore Franchino Ed Stevens 36. My Visit to Desbonnet . .John Grimek Candy Gaudiani Pudgy & Les Stockton 38. Best of Them All . .Terry Robinson 39. The First Great Bodybuilder . Jim Lorimer Rob Gilbert Frank Stranahan 40. Tribute to a Titan . .Tom Minichiello Fairfax Hackley Al Thomas 42. Grapevine . Staff James Hammill Ted Thompson 48. How Steve Reeves Trained . .John Grimek 50. John Grimek: Master of the Dance. Al Thomas Odd E. Haugen Joe Weider 64. “The Man’s Just Too Strong for Words”. John Fair Norman Komich Harold Zinkin Zabo Koszewski Co-Editors . , . Jan & Terry Todd FELLOWSHIP SUBSCRIBERS Business Manager . -

George Hackenschmidt Vs. Frank Gotch Media Representations and the World Wrestling Title of 1908 Kim Beckwith & Jan Todd the University of Texas

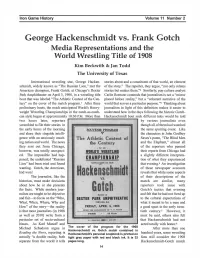

Iron Game History Volume 11 Number 2 George Hackenschmidt vs. Frank Gotch Media Representations and the World Wrestling Title of 1908 Kim Beckwith & Jan Todd The University of Texas International wrestling star, George Hacken- stories about and a constituent of that world, an element schmidt, widely known as "The Russian Lion," met the of the story." The reporter, they argue, "not only relates American champion, Frank Gotch, at Chicago's Dexter stories but makes them."2 Similarly, pop culture analyst Park Amphitheater on April 3, 1908, in a wrestling title Carlin Romano contends that journalism is not a "minor bout that was labeled "The Athletic Contest of the Cen- placed before reality," but a "coherent nanative of the tmy" on the cover of the match program.' After three world that serves a particular purpose."3 Thinking about preliminary bouts, the much anticipated World's Heavy- journalism in light of this definition makes it easier to weight Wrestling Championships in the catch-as-catch- understand how in the days following the historic Gotch can style began at approximately 10:30 P.M. More than Hackenschmidt bout such different tales would be told two hours later, reporters ...-------------------. by various journalists even scrambled to file their stories in though all of them had watched the early hours of the morning SOUVENIR PROGRAM the same spmting event. Like and share their ringside intelli- 'f the characters in John Godfrey gence with an anxiously await- The Athletic Contest of Saxes's poem, "The Blind Men ing nation and world. The news the Century and the Elephant," almost all they sent out from Chicago, _ For •h• _ of the reporters who pe1111ed however, was totally unexpect- WORLD'S WRESTLING their reports from Chicago had ed. -

Diplomová Práce Kulturismus a Revoluce

Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická fakulta Ústav hospodářských a sociálních dějin Diplomová práce Bc. Jiří Šabek Kulturismus a revoluce: K otázce sociálních dějin tělesnosti v Československu (The Bodybuilding Movement and Revolution: The Social History of Physicality in Czechoslovakia) Praha 2016 Vedoucí práce: Doc. PhDr. et JUDr. Jakub Rákosník, Ph.D. Rád bych tímto zde poděkoval v první řadě svému vedoucímu práce, panu docentu PhDr. et JUDr. Jakub Rákosníkovi, PhD., za veškerou odbornou pomoc v mém studiu. Dále bych rád poděkoval za pomoc i radu panu Josefu Švubovi, „kronikáři síly“ časopisu Muscle&Fitness, Ing. Martinu Jebasovi, předsedovi Svazu kulturistiky a fitness České republiky, a Ing. Josefu Paulíkovi, readaktorovi stránek Ronnie.cz. Mé velké díky patří bezesporu také mé rodině, zejména nekonečně trpělivé sestře, stejně jako všem mým přátelům, kteří mě po celou dobu studia podporovali. J. Š. Prohlašuji, že jsem svou diplomovou práci vypracoval samostatně, že jsem řádně citoval všechny použité prameny a literaturu a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu. V Praze dne………… podpis Abstrakt: Diplomová práce se snaží zpracovat téma fenoménu kulturistiky v širším kontextu utváření ideálního těla v moderní době. Kulturistika je chápána jako specifický socio-kulturní fenomén pevně spjatý s moderní společností a jejím historickým vývojem. Kromě samotné kulturistiky se tak práce zaobírá rozborem soudobé sociální teorie těla se zaměřením na domácí diskurs a v dalším kroku také analýzou diskursivního vytváření moderní tělesnosti od osvícenství do 20. století. Zde je kladen hlavní důraz na chápání charakteristických změn moderní společnosti v kontextu kontinuity celého modernizačního projektu. Hlavním cílem práce je popsat obecné dějin kulturistiky v rámci nastíněného procesu modernizace, stejně jako porovnání ruzných alternativních pojetí ideální tělesnosti v období tzv. -

“The Russian Lion”: Vladislav Von Krajewski's Bodybuilding of George Hachenschmidt Fae Brauer, Professor of Art A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UEL Research Repository at University of East London Making “The Russian Lion”: Vladislav von Krajewski’s Bodybuilding of George Hachenschmidt Fae Brauer, Professor of Art and Visual Culture University of East London Centre for Cultural Studies Research In their focus upon the rupture and transformation of Soviet physical culture in the 1930s, histories of Russian bodybuilding of the new man have tended to become disconnected from trajectories stretching back to the •Crimean War and the need to enhance military preparedness through modern sports and gymnastics inspired by the •German Turnen gymnastic societies. Valued for producing a disciplined subject in peacetime and a fearless fighter in war, these so-called “disciplinary exercises” were promoted in the •first gymnastics club of St. Petersburg from 1863, followed by the Pal’ma Gymnastics Society which quickly spread with branches in five cities. After the Moscow Gymnastics Society opened with meetings on Tsvetnoi Boulevard, in 1874, •Pyotr Lesgaft, the founder of Russian physical education introduced gymnastics into the army with gymnastic courses for army officers and civilians by 1896. Yet, as this paper will reveal, it was only through •Dr. V. F. Krajewski, founder of the •St. Petersburg Athletic and Cycling Club and physician to the •Tsar, that the St. Petersburg Amateur Weightlifting Society was opened in 1885. •It was only due to Dr Krajewski that a •gym for weightlifting opened with the first all-Russian weightlifting championship being held in April 1897 in St. Petersburg Mikhailovsky Manege. -

The Operational Aesthetic in the Performance of Professional Wrestling William P

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling William P. Lipscomb III Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Lipscomb III, William P., "The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3825. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3825 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE OPERATIONAL AESTHETIC IN THE PERFORMANCE OF PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by William P. Lipscomb III B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1990 B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1991 M.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1993 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 William P. Lipscomb III All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am so thankful for the love and support of my entire family, especially my mom and dad. Both my parents were gifted educators, and without their wisdom, guidance, and encouragement none of this would have been possible. Special thanks to my brother John for all the positive vibes, and to Joy who was there for me during some very dark days. -

Official Athletic Rules and Official Handbook

GROUP XII., No. 12A VBIC^ 10 CENTS J SEPTEMBER . 1910 K 'H ATHI/BTIC I/IBRARY «^^ Auxiliary Series viy^ Il«" •••;»»"• hV 563 J5i'R P45 'I! 11910 hei 1 A.Gi.Sralding & §ros. .,^. MAINTAIN THEIR OWN HOUSES > • FOR DISTRIBUTING THE Spalding ^^ COMPLETE LINE OF Athletic Goods ••" ';' . r IN THE FOLLOWING CITIES NEW YORK "'izT°I28 Nassau St. "29-33 W«sl 42d SI. NEWARK, N. J. 84S Broad Street BOSTON, MASS. 141 Federal Street Spalding's Athletic Library Anticipating the present ten- dency of the American people toward a healthful method of living and enjoyment, Spalding's Athletic Library was established in 1892 for the purpose of encouraging ath- letics in every form, not only by publishing the official rules and records pertaining to the various pastimes, but also by instructing, until to-day Spalding's Athletic Library is unique in its own par- ticular field and has been conceded the greatest educational series on athletic and physical training sub- jects that has ever been compiled. The publication of a distinct series of books devoted to athletic sports and pastimes and designed to occupy the premier place in America in its class was an early idea of Mr. A. G. Spalding, who was one of the first in America to publish a handbook devoted to sports, Spalding's Official A. G. Spalding athletic Base Ball Guide being the initial number, which was followed at intervals with other handbooks on the in '70s. sports prominent the . , . i ^ »«• a /- Spalding's Athletic Library has had the advice and counsel of Mr. A. -

A Briefly Annotated Bibliography of English Language Serial Publications in the Field of Physical Culture Jan Todd, Joe Roark and Terry Todd

MARCH 1991 IRON GAME HISTORY A Briefly Annotated bibliography of English Language Serial Publications in the Field of Physical Culture Jan Todd, Joe Roark and Terry Todd One of the major problems encountered when an attempt is made in January of 1869 and that we were unable to verify the actual starting to study the history of physical culture is that libraries have so seldom date of the magazine. saved (or subscribed to) even the major lifting, bodybuilding and “N.D.” means that the issue did not carry any sort of date. “N.M.” physical culture publications, let alone the minor ones. Because of this, means no month was listed. “N.Y.” means no year was listed. “N.V.” researchers have had to rely for the most part on private collections for means that no volume was listed. “N.N.” means that no issue number their source material, and this has limited the academic scholarship in was assigned. A question mark (?) beside a date means that we are the field. This problem was one of the major reasons behind the estimating when the magazine began, based on photos or other establishment of the Physical Culture Collection at the University of evidence. Texas in Austin. The designation “Current” means that, as of press time, the Over the last several months, we have made an attempt to magazine was still being published on a regular basis. You will also assemble a comprehensive listing or bibliography of the English- note the designation “LIC.” This stands for “Last in Collection.” This language magazines (and a few notable foreign language publications) simply means that the last copy of the magazine we have on hand here in the field of physical culture. -

SOME THOUGHTS on the BODY: “HOW IT MEANS” and WHAT IT MEANS Our Friend, Al Thomas, Sent the Following Thoughts to Us Some Values That Weight Training Confers

VOLUME 2 NUMBER 5 January 1993 SOME THOUGHTS ON THE BODY: “HOW IT MEANS” AND WHAT IT MEANS Our friend, Al Thomas, sent the following thoughts to us some values that weight training confers. months back. He didn’t intend for us to publsih them; he only The film, it seems, had created the need for explanation to so many wanted to share with us what was on his mind. Even so, we have people that it became a sort of emotional watershed for me. Or, more decided to share his thoughts with you. As some of you know, Al accurately, it was the film, plus the fact that, having passed through has made seminal contributions to our game—particularly in a my fifties and the first year of my sixties, I was faced with retirement series of articles in Iron Man concerning women, strength and from my profession as a college teacher. With the ticking-down of physical development. He made these contributions simply by the machine that is symbolized by such life-changes, I began to focusing his long experience and his agile intelligence on the issue. wonder what truly had become my “value system”: Was the new What follows is a fascinating display of unexpurgated Thomas one that seemed to be a response to my film really as unworthy of a confronting certain ultimate questions. What follows is not for balding college professor with a Ph.D. as it seemed? the timid. What follows is a love song. As recently as a year ago, I would have claimed my family and (This has its origin in three questions posed at the recent Old-timers’ my profession (along with one or two other traditionally acceptable banquet. -

Yearning for Muscular Power

IGH Vol 9 (3) January 2007 Final to Speedy:IGH Vol 9 (1) July 2005 final to Speedy.qxd 10/10/2011 11:50 PM Page 20 Iron Game History Volume 9 Number 3 Yearning for Muscular Power Terry Todd and John Hoberman The University of Texas at Austin Young men dream of power. It is an old dream, dred pounds at a time when most heavyweight boxers driven in boyhood by a relative lack of it and later by a weighed less than 190. His heavy bone-structure was belief in what it will confer in manhood. The dream overlaid with abnormally dense muscling and his hands, often comes through images of masculine strength— in particular, were huge and work-hardened. It was said heroically muscled athletes, forceful warriors, comic of him that when he gripped a bat it looked as if he could book superheroes, action figures in films and video squeeze sawdust out of it. He was, by far, the greatest games. The dream, at its core, is a dream of transforma - home run hitter in Negro League history, and some base - tion—from short to tall, thin to thick, fat to lean, weak to ball historians believe that, had he been allowed to play strong. in the Major Leagues, he would have hit more home runs Since well before the time of Christ, a few peo - than his contemporary, Babe Ruth. 1 ple have known a secret which could en-flesh most of Apparently, Gibson did hit more home runs than these dreams. That secret is progressive resistance exer - Ruth’s 714—almost eight hundred, by the best esti - cise. -

Where Are They Now? Joe Assirati: Reminiscences of Britains Renaissance of Strength

IRON GAME HISTORY VOLUME 2 NUMBER 5 Joe Assirati: Reminiscences of Britain’s Renaissance of Strength Al Thomas, Ph.D. Like all history, iron game his- its heroes. It’s instructive, of course, to tory is stories. The history here comes attend to the tale-as-tale and to find to us from strongman storyteller, Joe in it yet another piece with which to Assirati, one of the few extant eye wit- complete, and give meaning to, the iron nesses to the most colorful epoch in the game puzzle that each of us carries annals of British strengthdom. The around, unfinished, in his mind. But closer to the fact-ness of the past event, even more, it’s sweet to feel, in the sto- the better and more authoritative the ryteller’s telling, his love for our won- history. But truly objective history derful game and its history. doesn’t exist. However stoutly pur- When Terry and Jan Todd returned sued, there is, in history, always the from a recent trip to England, they alloy of the teller’s perception, preju- spoke glowingly about meeting and dice, and predisposition: in short, his working out with Joe Assirati (of the personality. And without this aura of famous Assirati clan, cousin of Bert), personality, there would be no joy in a marvelous specimen of weight- stories and their telling, and (to come trained manhood, 87-years-old, an full circle) without stories and their inveterate storyteller. Encouraged by telling, there would be precious little the Todds, I wrote to Joe and discov- history. -

Kapitoly Z Vývoje Sportovních Disciplín Utvářejících Dnešní Podobu Fitness

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE Fakulta tělesné výchovy a sportu Kapitoly z vývoje sportovních disciplín utvářejících dnešní podobu fitness Diplomová práce Vedoucí diplomové práce: Zpracoval: PhDr. František Kolář, CSc. Jan Lufinka srpen 2010 ABSTRAKT Název práce: Kapitoly z vývoje sportovních disciplín utvářejících dnešní podobu fitness. Cíle práce: Cíl mojí diplomové práce je především v co možném nejširším náhledu představit sportovní disciplíny a jejich vývoj od počátku civilizace do současnosti, které daly základ dnešnímu modernímu trendu fitness ve světě i v České republice. Dále je mým cílem shromáždit co nejvíce poznatků a materiálů o těchto disciplínách. Které chci podrobněji popsat a představit čtenářovi tak, aby pochopil, že právě zde je historický základ trendu zvaný fitness. Metoda: Při sestavování této diplomové práce jsem čerpal především z literatury, zabývající se odvětvím fitness, kulturistikou, vzpíráním, těžkou atletikou, historií, bájemi a mýty. Dále jsem čerpal z internetu, z archivních pramenů, statistik, rozhovorů a časopisů. Velmi mi také pomohly vlastní zkušenosti v oboru fitness. Výsledky: Ukazují a popisují historii fitness a podobných sportovních aktivit od počátku civilizace ve světě a v České republice. Klíčová slova: fitness, kulturistika, těžká atletika, historie, tělovýchova. ABSTRACT Work title: Chapters from the evolution of sporting disciplines forming the appearance of today's fitness. Work objectives: Purpose of my thesis is first of all to introduce in the broadest possible view sporting disciplines and their evolution, from early civilization to the present, which gave the basis for today's modern trend fitness in the world and in the Czech Republic. Furthermore, my object is to gather as much pieces of knowledge and materials about these disciplines. -

Dinosaur Training Lost Secrets of Strength And

DINOSAUR TRAINING LOST SECRETS OF STRENGTH AND DEVELOPMENT Brooks D. Kubik Dinosaur Training – Brooks Kubik TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................ 2 PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION............................................................................... 3 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION .......................................................................... 6 CHAPTER ONE: THE DINOSAUR ALTERNATIVE......................................................... 7 CHAPTER TWO: PRODUCTIVE TRAINING.................................................................. 13 CHAPTER THREE: AN OUTLINE OF DINOSAUR TRAINING .................................... 17 CHAPTER FOUR: HARD WORK .................................................................................... 26 CHAPTER FIVE: DINOSAUR EXERCISES .................................................................... 33 CHAPTER SIX: ABBREVIATED TRAINING.................................................................. 39 CHAPTER SEVEN: HEAVY WEIGHTS .......................................................................... 43 CHAPTER EIGHT: POUNDAGE PROGRESSION.......................................................... 50 CHAPTER NINE: DEATH SETS ...................................................................................... 56 CHAPTER TEN: MULTIPLE SETS OF LOW REPS ........................................................ 59 CHAPTER ELEVEN: SINGLES......................................................................................