Tetepare Visitor Guidebook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title Butterflies Collected in and Around Lambir Hills National Park

Butterflies collected in and around Lambir Hills National Park, Title Sarawak, Malaysia in Borneo ITIOKA, Takao; YAMAMOTO, Takuji; TZUCHIYA, Taizo; OKUBO, Tadahiro; YAGO, Masaya; SEKI, Yasuo; Author(s) OHSHIMA, Yasuhiro; KATSUYAMA, Raiichiro; CHIBA, Hideyuki; YATA, Osamu Contributions from the Biological Laboratory, Kyoto Citation University (2009), 30(1): 25-68 Issue Date 2009-03-27 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/156421 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Contn bioL Lab, Kyoto Univ., Vot. 30, pp. 25-68 March 2009 Butterflies collected in and around Lambir Hills National ParK SarawaK Malaysia in Borneo Takao ITioKA, Takuji YAMAMo'rD, Taizo TzucHiyA, Tadahiro OKuBo, Masaya YAGo, Yasuo SEKi, Yasuhiro OHsHIMA, Raiichiro KATsuyAMA, Hideyuki CHiBA and Osamu YATA ABSTRACT Data ofbutterflies collected in Lambir Hills National Patk, Sarawak, Malaysia in Borneo, and in ks surrounding areas since 1996 are presented. In addition, the data ofobservation for several species wimessed but not caught are also presented. In tota1, 347 butterfly species are listed with biological information (habitat etc.) when available. KEY WORDS Lepidoptera! inventory1 tropical rainforesti species diversity1 species richness! insect fauna Introduction The primary lowland forests in the Southeast Asian (SEA) tropics are characterized by the extremely species-rich biodiversity (Whitmore 1998). Arthropod assemblages comprise the main part of the biodiversity in tropical rainforests (Erwin 1982, Wilson 1992). Many inventory studies have been done focusing on various arthropod taxa to reveal the species-richness of arthropod assemblages in SEA tropical rainforests (e.g. Holloway & lntachat 2003). The butterfly is one of the most studied taxonomic groups in arthropods in the SEA region; the accumulated information on the taxonomy and geographic distribution were organized by Tsukada & Nishiyama (1980), Yata & Morishita (1981), Aoki et al. -

A Compilation and Analysis of Food Plants Utilization of Sri Lankan Butterfly Larvae (Papilionoidea)

MAJOR ARTICLE TAPROBANICA, ISSN 1800–427X. August, 2014. Vol. 06, No. 02: pp. 110–131, pls. 12, 13. © Research Center for Climate Change, University of Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia & Taprobanica Private Limited, Homagama, Sri Lanka http://www.sljol.info/index.php/tapro A COMPILATION AND ANALYSIS OF FOOD PLANTS UTILIZATION OF SRI LANKAN BUTTERFLY LARVAE (PAPILIONOIDEA) Section Editors: Jeffrey Miller & James L. Reveal Submitted: 08 Dec. 2013, Accepted: 15 Mar. 2014 H. D. Jayasinghe1,2, S. S. Rajapaksha1, C. de Alwis1 1Butterfly Conservation Society of Sri Lanka, 762/A, Yatihena, Malwana, Sri Lanka 2 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Larval food plants (LFPs) of Sri Lankan butterflies are poorly documented in the historical literature and there is a great need to identify LFPs in conservation perspectives. Therefore, the current study was designed and carried out during the past decade. A list of LFPs for 207 butterfly species (Super family Papilionoidea) of Sri Lanka is presented based on local studies and includes 785 plant-butterfly combinations and 480 plant species. Many of these combinations are reported for the first time in Sri Lanka. The impact of introducing new plants on the dynamics of abundance and distribution of butterflies, the possibility of butterflies being pests on crops, and observations of LFPs of rare butterfly species, are discussed. This information is crucial for the conservation management of the butterfly fauna in Sri Lanka. Key words: conservation, crops, larval food plants (LFPs), pests, plant-butterfly combination. Introduction Butterflies go through complete metamorphosis 1949). As all herbivorous insects show some and have two stages of food consumtion. -

Exploitation of Lycaenid-Ant Mutualisms by Braconid Parasitoids

31(3-4):153-168,Journal of Research 1992 on the Lepidoptera 31(3-4):153-168, 1992 153 Exploitation of lycaenid-ant mutualisms by braconid parasitoids Konrad Fiedler1, Peter Seufert1, Naomi E. Pierce2, John G. Pearson3 and Hans-Thomas Baumgarten1 1 Theodor-Boveri-Zentrum für Biowissenschaften, Lehrstuhl Zoologie II, Universität Würzburg, Am Hubland, D-97074 Würzburg, Germany 2 Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, 26 Oxford Street, Cambridge, MA 02138-2902, USA 3 Division of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Western State College, Gunnison, CO 81230, USA Abstract. Larvae of 17 Lycaenidae butterfly species from Europe, North America, South East Asia and Australia were observed to retain at least some of their adaptations related to myrmecophily even after parasitic braconid larvae have emerged from them. The myrme- cophilous glandular organs and vibratory muscles of such larval carcasses remain functional for up to 8 days. The cuticle of lycaenid larvae contains extractable “adoption substances” which elicit anten- nal drumming in their tending ants. These adoption substances, as well, appear to persist in a functional state beyond parasitoid emer- gence, and the larval carcasses are hence tended much like healthy caterpillars. In all examples, the braconids may receive selective advantages through myrmecophily of their host larvae, instead of being suppressed by the ant guard. Interactions where parasitoids exploit the ant-mutualism of their lycaenid hosts have as yet been recorded only from the Apanteles group in the Braconidae- Microgasterinae. KEY WORDS: Lycaenidae, Formicidae, myrmecophily, adoption sub- stances, parasitoids, Braconidae, Apanteles, defensive mechanisms INTRODUCTION Parasitoid wasps or flies are major enemies of the early stages of most Lepidoptera (Shaw 1990, Weseloh 1993). -

Land and Maritime Connectivity Project: Road Component Initial

Land and Maritime Connectivity Project (RRP SOL 53421-001) Initial Environmental Examination Project No. 53421-001 Status: Draft Date: August 2020 Solomon Islands: Land and Maritime Connectivity Project – Multitranche Financing Facility Road Component Prepared by Ministry of Infrastructure Development This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to any particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Solomon Islands: Land and Maritime Connectivity Project Road Component – Initial Environmental Examination Table of Contents Abbreviations iv Executive Summary v 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to the Project 1 1.2 Scope of the Environmental Assessment 5 2 Legal and Institutional Framework 6 2.1 Legal and Planning Framework 6 2.1.1 Country safeguard system 6 2.1.2 Other legislation supporting the CSS 7 2.1.3 Procedures for implementing the CSS 9 2.2 National Strategy and Plans 10 2.3 Safeguard Policy Statement 11 3 Description of the Subprojects 12 3.1 Location and Existing Conditions – SP-R1 12 3.1.1 Existing alignment 12 3.1.2 Identified issues and constraints 14 3.2 Location and Existing Conditions – SP-R5 15 3.2.1 Location -

Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae: Lipteninae) Uses a Color-Generating Mechanism Widely Applied by Butterflies

Journal of Insect Science, (2018) 18(3): 6; 1–8 doi: 10.1093/jisesa/iey046 Research The Only Blue Mimeresia (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae: Lipteninae) Uses a Color-Generating Mechanism Widely Applied by Butterflies Zsolt Bálint,1,5 Szabolcs Sáfián,2 Adrian Hoskins,3 Krisztián Kertész,4 Antal Adolf Koós,4 Zsolt Endre Horváth,4 Gábor Piszter,4 and László Péter Biró4 1Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest, Hungary, 2Faculty of Forestry, University of West Hungary, Sopron, Hungary, 3Royal Entomological Society, London, United Kingdom, 4Institute of Technical Physics and Materials Science, Centre for Energy Research, Budapest, Hungary, and 5Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Subject Editor: Konrad Fiedler Received 21 February 2018; Editorial decision 25 April 2018 Abstract The butterflyMimeresia neavei (Joicey & Talbot, 1921) is the only species in the exclusively African subtribal clade Mimacraeina (Lipteninae: Lycaenidae: Lepidoptera) having sexual dimorphism expressed by structurally blue- colored male and pigmentary colored orange–red female phenotypes. We investigated the optical mechanism generating the male blue color by various microscopic and experimental methods. It was found that the blue color is produced by the lower lamina of the scale acting as a thin film. This kind of color production is not rare in day-flying Lepidoptera, or in other insect orders. The biological role of the blue color of M. neavei is not yet well understood, as all the other species in the clade lack structural coloration, and have less pronounced sexual dimorphism, and are involved in mimicry-rings. Key words: Africa, Lycaenidae, mimicry, thin film, wing scale The late John Nevill Eliot in his fundamental work on Lycaenidae blue dorsal wing surface, whilst the female with its bright orange classification subdivided the family into sections, tribes, and sub- appearance is a typical mimeresine. -

CONSERVATION STRATEGY for the ISLAND of TETEPARE Report Prepared by Bill

CONSERVATION STRATEGY FOR THE ISLAND OF TETEPARE Report prepared by Bill Carter with the assistance of Friends of Tetepare and WWF South Pacific Program August 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This strategy is the result of a Skills for Community Based Conservation Workshop conducted as part of the World Wide Fund for Nature’s Solomon Islands Community Resource and Conservation and Development Project in June 1997. The workshop was attended by 24 descendants of the people of Tetepare who departed the Island c1850. It follows an initial workshop in November 1996 facilitated by WWF South Pacific Program. The strategy is strongly based on the outputs of these workshops and to this extent, the contribution of Niva Aloni, John Aqorau, Mary Bea, Kido Dalipada, Tennet Dalipada, Darald Galo, Elaine Galo, Matthew Garunu, Tui Kavusu, Katalulu Mapioh, Isaac Molia, Julie Poa, Glen Pulekolo, Kenneth Roga, Peter Siloko, Sara Siloko, Pitrie Sute, Medos Tivikera and Bili Vinajama must be recognized. Any misrepresentation of fact, opinion or intentions expressed by workshop participants is solely the error of the author. In the absence of published information on Tetepare, this strategy has relied heavily on workshop participant information and reports and records provided by the Solomon Islands Ministry of Forest, Environment and Conservation as well as the excellent and unpublished archaeological work of Kenneth Roga (Western province, Division of Culture, Environment, Tourism and Women). The foundation laid by Kath Means, Seri Hite and Lorima Tuke of WWF in conducting the November 1996 workshop, assisting in June 1997 workshop and their support in preparing this strategy is gratefully acknowledged. However, it is the Friends of Tetepare who, through its Chair Isaac Molia and Coordinator Kido Dalipada, deserve most credit for this initiative. -

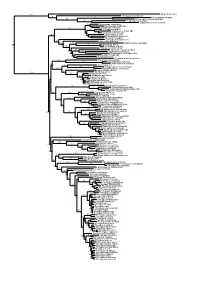

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

Phylogenetic Perspectives on Viviparity, Gene-Tree Discordance, and Introgression in Lizards (Squamata)

Phylogenetic Perspectives on Viviparity, Gene-Tree Discordance, and Introgression in Lizards (Squamata) Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Lambert, Shea Maddock Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 08:50:17 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/630229 1 PHYLOGENETIC PERSPECTIVES ON VIVIPARITY, GENE-TREE DISCORDANCE, AND INTROGRESSION IN LIZARDS (SQUAMATA). by Shea Maddock Lambert ____________________________ Copyright © Shea Maddock Lambert 2018 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 THEUNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE Asmembers of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Shea M. Lambert, titled "Phylogenetic perspectives on viviparity,gene-tree discordance, and introgressionin lizards {Squamata)" and recomme11dthat it be accepted as fulfillingthe dissertation requirem�t for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _.c.---� ---------Date: May 21, 2018 _wJohn__ . �e� --�_:-_:-__:_ W_ -----�----'-------------------Date: May 21, 2018 Michael Barker M ichael ( s��t=t ��A". =----.�+o/-�i � -\.\----�--------._______ Date: May 21, 2018 Noa�man Final approval and acceptance· of this dissertation is contingent uporithe candidate's submission of the final copies of the· dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my ditettion and recommend that it be accepted as fulfillin_;the �issertation requirement. -

Asia-Pacific UN Office in Bankok Association Association Coordinator@Kibca,Org 1968

Name of the Name of the Title Address/Country Telephone/Fax/e- Website Language(s) Question #1 Question #2 Question #3 Question #4 candidate Organization or mail Spoken Network Ferguson Vaghi Kolombangara Programme Kolombangara Mobile: 677 www. 1. English Kolombangara Island Biodiversity Our own experience is good example. KIBCA believes in multi_stakeholder engagement. We do have an advisory arrangements with UN-REDD and Island Biodiversity Coordinator Island Biodiversity 7401198 kolombangara.org 2.Pinjin Conservation Association interest is in We have a Community Conservation Agreement the Solomon Islands Government Ministry of Environment. Conservation Conservation email: 3.Nduke Conservation and Biological Management. Kolombangara island has been logged since with the American Museum of natural History, With Financial support from Asia-Pacific UN office in Bankok Association Association coordinator@kibca,org 1968. Since then the effects of logging have This organization supports us in Conservation and i have been invited to attend the anti-corruption training in (KIBCA), Our Associations function is to promote & been felt by the local Communities in terms Biological management. It collaborates in 5 major Bankok in November 2011. P O Box 199, encourage Sustainable resource of climate change, soil degradation, water sites in the Solomons. We also have partnership Gizo, Management. To protect the rights of the pollution, social breakdown and the with the Solomon Islands Government Ministry of The American museum of natural history with the clear sky Western Province. resource owners in terms of exploitation of destruction of the basis of our livelihood and Forestry and the Ministry of Environment. The consultancy have done a training on REDD+ in our project Solomon Islands resources by corrupt practices through a continuation of illegal logging in the Island. -

Species Boundaries, Biogeography, and Intra-Archipelago Genetic Variation Within the Emoia Samoensis Species Group in the Vanuatu Archipelago and Oceania" (2008)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 Species boundaries, biogeography, and intra- archipelago genetic variation within the Emoia samoensis species group in the Vanuatu Archipelago and Oceania Alison Madeline Hamilton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Recommended Citation Hamilton, Alison Madeline, "Species boundaries, biogeography, and intra-archipelago genetic variation within the Emoia samoensis species group in the Vanuatu Archipelago and Oceania" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3940. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3940 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SPECIES BOUNDARIES, BIOGEOGRAPHY, AND INTRA-ARCHIPELAGO GENETIC VARIATION WITHIN THE EMOIA SAMOENSIS SPECIES GROUP IN THE VANUATU ARCHIPELAGO AND OCEANIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Biological Sciences by Alison M. Hamilton B.A., Simon’s Rock College of Bard, 1993 M.S., University of Florida, 2000 December 2008 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my graduate advisor, Dr. Christopher C. Austin, for sharing his enthusiasm for reptile diversity in Oceania with me, and for encouraging me to pursue research in Vanuatu. His knowledge of the logistics of conducting research in the Pacific has been invaluable to me during this process. -

Entomologische Zeitung Stettin

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Entomologische Zeitung Stettin Jahr/Year: 1908 Band/Volume: 69 Autor(en)/Author(s): Fruhstorfer Hans Artikel/Article: Neue Curetis und Übersicht der bekannten Arten 49-59 ©Biodiversity Heritage Library, www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zobodat.at 49 Neue Curetis und Uebersicht der bekannten Arten von II. Frulistorfer. Wenngleich mir aus Süd-Asien 135 und allein aus Java 80 Exempl. vorliegen ist es mir nicht möglich mehr als 5 Arten Curetis zu unterscheiden, während de Niceville in Butterflies India nicht weniger als ,,13 Arten" nur aus Nord-Indien und Birma, und Distant, Rhopalocera Malayana deren 5 von der Malay. Halbinsel registriert. In der Hauptsache haben wir es mit 2 Gruppen von Individuen zu tun, die sich recht gut insgesamt auf 4 Species alter Autoren zurückführen lassen. Die vielen Moore'schen und Felder'schen ,, Species" bezeichnen dagegen fast aus- schließlich Lokalrassen, Zeitformen und vielfach sogar nur individuelle Formen. Bei den Ctiretis macht sich nämlich ein bei den Lycae- niden kaum beobachteter, weitgehender männlicher Poly- morphismus bemerklich, wie wir ihn in noch höherem Grade, unter den Nymphaliden etwa bei einigen Euthaliiden und Euphaedra-Arten wiederfinden und dieser Polymorphismus verleitete die Autoren zur Creierung der vielen Arten! Meine heutigen Zeilen sollen dazu beitragen die Sy- nonymie der Curetis etwas zu klären und die Kenntnis einiger neuer Formen meiner letzten Reisen vermitteln. I. Gruppe. Hinterflügel rundlich. A. $ mit weißen Discalflecken. I. Curetis thetis Drury. a) thetis thetis Drury. Bombay (Drury). = P. phaedrus F. ,,Habitat in India orientali" (^. = P. aesopus F. -

Species-Edition-Melanesian-Geo.Pdf

Nature Melanesian www.melanesiangeo.com Geo Tranquility 6 14 18 24 34 66 72 74 82 6 Herping the final frontier 42 Seahabitats and dugongs in the Lau Lagoon 10 Community-based response to protecting biodiversity in East 46 Herping the sunset islands Kwaio, Solomon Islands 50 Freshwater secrets Ocean 14 Leatherback turtle community monitoring 54 Freshwater hidden treasures 18 Monkey-faced bats and flying foxes 58 Choiseul Island: A biogeographic in the Western Solomon Islands stepping-stone for reptiles and amphibians of the Solomon Islands 22 The diversity and resilience of flying foxes to logging 64 Conservation Development 24 Feasibility studies for conserving 66 Chasing clouds Santa Cruz Ground-dove 72 Tetepare’s turtle rodeo and their 26 Network Building: Building a conservation effort network to meet local and national development aspirations in 74 Secrets of Tetepare Culture Western Province 76 Understanding plant & kastom 28 Local rangers undergo legal knowledge on Tetepare training 78 Grassroots approach to Marine 30 Propagation techniques for Tubi Management 34 Phantoms of the forest 82 Conservation in Solomon Islands: acts without actions 38 Choiseul Island: Protecting Mt Cover page The newly discovered Vangunu Maetambe to Kolombangara River Island endemic rat, Uromys vika. Image watershed credit: Velizar Simeonovski, Field Museum. wildernesssolomons.com WWW.MELANESIANGEO.COM | 3 Melanesian EDITORS NOTE Geo PRODUCTION TEAM Government Of Founder/Editor: Patrick Pikacha of the priority species listed in the Critical Ecosystem [email protected] Solomon Islands Hails Partnership Fund’s investment strategy for the East Assistant editor: Tamara Osborne Melanesian Islands. [email protected] Barana Community The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) Contributing editor: David Boseto [email protected] is designed to safeguard Earth’s most biologically rich Prepress layout: Patrick Pikacha Nature Park Initiative and threatened regions, known as biodiversity hotspots.