Werowocomoco: Seat of Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The York River: a Brief Review of Its Physical, Chemical and Biological Characteristics

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 1986 The York River: A Brief Review of Its Physical, Chemical and Biological Characteristics Michael E. Bender Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Marine Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Bender, M. E. (1986) The York River: A Brief Review of Its Physical, Chemical and Biological Characteristics. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/V5JD9W This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The York River: A Brief Review of Its Physical, Chemical and Biological Characteristics ·.by · Michael E. Bender .·· Virginia Institute of Marine Science School ofMar.ine Science The College of William and Mary Gloucester, Point; Virginia 23062 The York River: A Brief Review of Its Physical, Chemical and Biological Characteristics by · Michael E. Bender Virginia Institute of Marine Science School of Marine Science The College of William and Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. The York River . 5 2. The York River Basin (to the fall line) .. 6 3. Mean Daily Water Temperatures off VIMS Pier for 1954- 1977 [from Hsieh, 1979]. • . 8 4. Typical Water Temperature Profiles in the Lower York River approximately 10 km from the River Mouth . 10 5. Typical Seasonal Salinity Profiles Along the York River. -

James River Geography

James River Geography Welcome to NOAA's James River Interpretive Buoy, located at latitude 37 degrees 12.25 minutes North, longitude 76 degrees 46.65 minutes West. It lies off Jamestown Island about a quarter-mile south of Captain John Smith's statue, where he can see it well as he looks out over the river. This buoy is anchored in 43 feet of water at the edge of the narrow shoal that runs along the island. The river's channel is deep here, as the James narrows down between Swanns Point on the south and Jamestown on the north, but it quickly shoals as it sweeps through the broad meander curve from Cobham Bay around Hog Island and down toward Burwell Bay. The buoy lies about thirty miles above the mouth of the James at Hampton Roads. Jamestown Island lies at a transition point on the James. Five miles upstream is the mouth of the Chickahominy River, which adds a strong current of fresh water to the heavy flow already coming out of the James watershed from deep in Virginia's uplands, the mountains at the eastern edge of the Alleghany Plateau. In wet years, the water here is nearly fresh. The mouth of the James, however, lies close to the Chesapeake's mouth, so salt water can also flow upriver with the tides. In John Smith's time here, the region suffered a multi-year drought, so the river and the colonists' drinking water was probably brackish, an irritating factor that may account for some of the bickering and poor health that plagued them. -

Werowocomoco Was Principal Residence of Powhatan

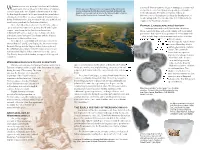

erowocomoco was principal residence of Powhatan, afterwards Werowocomoco began to emerge as a ceremonial paramount chief of 30-some Indian tribes in Virginia’s A bird’s-eye view of Werowocomoco as it appears today in Gloucester W and political center for Algonquian-speaking communities coastal region at the time English colonists arrived in 1607. County. Bordered by the York River, Leigh Creek (left) and Bland Creek (right), the archaeological site is listed on the National Register of Historic in the Chesapeake. The process of place-making at Archaeological research in the past decade has revealed not Places and the Virginia Historic Landmarks Register. Werowocomoco likely played a role in the development of only that the York River site was a uniquely important place social ranking in the Chesapeake after A.D. 1300 and in the during Powhatan’s time, but also that its role as a political and origins of the Powhatan chiefdom. social center predated the Powhatan chiefdom. More than 60 artifacts discovered at Werowocomoco Power, Landscape and History – projectile points, stone tools, pottery sherds and English Landscapes associated with Amerindian chiefdoms – copper – are shown for the fi rst time at Jamestown that is, regional polities with social ranking and institutional Settlement with archaeological objects from collections governance that organized a population of several thousand of the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation and the Virginia – often include large-scale or monumental architecture that Department of Historic Resources. transformed space within sacropolitical centers. Developed in cooperation with Werowocomoco site Throughout the Chesapeake region, Native owners Robert F. and C. Lynn Ripley, the Werowocomoco communities constructed boundary ditches Research Group and the Virginia Indian Advisory Board, and enclosures within select towns, marking the exhibition also explores what Werowocomoco means spaces in novel ways. -

The Lincoln- Mcclellan Relationship in Myth and Memory

The Lincoln- McClellan Relationship in Myth and Memory MARK GRIMSLEY Like many Civil War historians, I have for many years accepted invita- tions to address the general public. I have nearly always tried to offer fresh perspectives, and these have generally been well received. But almost invariably the Q and A or personal exchanges reveal an affec- tion for familiar stories or questions. (Prominent among them is the query “What if Stonewall Jackson had been present at Gettysburg?”) For a long time I harbored a private condescension about this affec- tion, coupled with complete incuriosity about what its significance might be. But eventually I came to believe that I was missing some- thing important: that these familiar stories, endlessly retold in nearly the same ways, were expressions of a mythic view of the Civil War, what the amateur historian Otto Eisenschiml memorably labeled “the American Iliad.”1 For Eisenschiml “the American Iliad” was merely a clever title for a compendium of eyewitness accounts of the conflict, but I take the term seriously. In Homer’s Iliad the anger of Achilles, the perfidy of Agamemnon, the doomed gallantry of Hector—and the relationships between them—have enormous, uncontested, unchanging, and almost primal symbolic meaning. So too do certain figures in the American Iliad. Prominent among these are the butcher Grant, the Christ-like Lee, and the rage- filled Sherman. I believe that the traditional Civil War narrative functions as a national myth of central importance to our understanding of ourselves as Americans. And like the classic mythologies of old, it contains timeless wisdom about what it means to be a human being. -

Fall 2004 Understanding 19Th-Century Industry • The

UNDERSTANDING 19TH-CENTURY INDUSTRY • THE BIRTH OF THE MAYA • PREHISTORY DEFROSTED FALL 2004 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 8 No. 3 43> $3.95 7525274 91765 archaeological tours led by noted scholars superb itineraries, unsurpassed service For the past 29 years, Archaeological Tours has been arranging specialized tours for a discriminating clientele. Our tours feature distinguished scholars who stress the historical, anthropological and archaeological aspects of the areas visited. We offer a unique opportunity for tour participants to see and understand historically important and culturally significant areas of the world. Professor Barbara Barletta in Sicily SICILY & SOUTHERN ITALY VIETNAM GREAT MUSEUMS: Byzantine to Baroque Touring includes the Byzantine and Norman monuments Beginning with Hanoi’s rmuseums and ancient pagodas, As we travel from Assisi to Venice, this spectacular tour of Palermo, the Roman Villa in Casale, unique for its 37 we continue into the heartland to visit some of the ethnic will offer a unique opportunity to trace the development rooms floored with exquisite mosaics, Phoenician Motya minorities who follow the traditions of their ancester’s. We of art and history out of antiquity toward modernity in and classical Segesta, Selinunte, Agrigento and will see the temples and relics of the ancient Cham both the Eastern and Western Christian worlds. The Siracusa — plus, on the mainland, Paestum, Pompeii, peoples, and the villages and religious institutions of the tour begins with four days in Assisi, including a day trip Herculaneum and the incredible "Bronzes of Riace." modern Cham. In the imperial city of Hue, marvelous to medieval Cortona. -

Success Stories

SUCCESS STORIES PLANT NAME AND LOCATION YORK RIVER TREATMENT PLANT (HAMPTON ROADS SANITATION DISTRICT) - YORK RIVER, VA DESIGN DAILY FLOW / PEAK FLOW 0.5 MGD (1893 M3/DAY) / 0.5 MGD (1893 M3/DAY) AQUA-AEROBIC SOLUTION SINGLE-BASIN AquaSBR® SYSTEM, 4-DISK AquaDisk® FILTER AQUA-AEROBIC TECHNOLOGIES CHOSEN FOR FIRST MUNICIPAL- INDUSTRIAL WATER REUSE PROJECT IN VIRGINIA! Hampton Roads Sanitation District (HRSD) was created in 1940 to reduce pollution in the Chesapeake Bay. It currently serves a population of approximately 1.6 million with nine regional wastewater treatment plants in Hampton Roads and four smaller plants on Virginia’s Middle Peninsula. HRSD set the goal to reuse its treated wastewater for nonpotable purposes in the 1980s. An oil refi nery located next to their York River Treatment Plant (YRTP) approached HRSD in 1996 to supply reclaimed water for the refi nery’s cooling and process water. Previously, the refi nery utilized increasingly expensive potable water and upgrading its own treatment facilities was too large an investment. In December 2000, HRSD signed a 20-year agreement to provide the refi nery with 0.5 MGD of reclaimed water. This was Virginia’s fi rst municpal-industrial water reuse project! York River’s AquaSBR® basin in operation. Since the existing activated sludge treatment process at water can be fed to the AquaDisk fi lter from either the full- HRSD’s York River Treatment Plant couldn’t reliably meet the scale plant effl uent or the sidestream AquaSBR system. refi nery’s special target requirements for both low turbidity and year-round ammonia concentration, other treatment HRSD sells the reclaimed water to the refi nery at cost, processes had to be investigated. -

Pocahontas and Captain John Smith Revisited

Pocahontas and Captain John Smith Revisited FREDERIC W. GLEACH Cornell University The story of Pocahontas and Captain John Smith is one that all school children in the United States seem to learn early on, and one that has served as the basis for plays, epic poems, and romance novels as well as historical studies. The lyrics of Peggy Lee's hit song Fever exemplify these popular treatments: Captain Smith and Pocahontas Had a very mad affair. When her daddy tried to kill him She said, 'Daddy, oh don't you dare — He gives me fever ... with his kisses, Fever when he holds me tight; Fever — I'm his Mrs. Daddy won't you treat him right.' (Lee et al 1958) The incident referred to here, Pocahontas's rescue of Smith from death at the orders of her father, the paramount chief Powhatan, was originally recorded by the only European present — Smith himself. While the factu- ality of Smith's account has been questioned since the mid-19th century, recent textual analysis by Lemay (1992) supports the more widely held opinion that it most likely occurred as Smith reported. Other recent studies have employed methods and models imported from literary criticism, gen erally to demonstrate the nature of English colonial and historical modes of apprehending otherness.1 While my work may be easily contrasted to these approaches, two re cent studies must be mentioned which have employed understandings and methods similar to my own. Kidwell (1992:99-101) used Pocahontas as an example in her discussion of "Indian Women as Cultural Mediators", 1ln addition to the comments of participants in the Algonquian Conference I have had the benefit of discussion with members of the Department of Anthropol ogy of Cornell University, where I presented some of these ideas in a departmental colloquium. -

Simulated Changes in Salinity in the York and Chickahominy Rivers from Projected Sea-Level Rise in Chesapeake Bay

Prepared in cooperation with the City of Newport News Simulated Changes in Salinity in the York and Chickahominy Rivers from Projected Sea-Level Rise in Chesapeake Bay Open-File Report 2011–1191 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover photograph: St. Michaels Marina, Chesapeake Bay, Maryland. Simulated Changes in Salinity in the York and Chickahominy Rivers from Projected Sea-Level Rise in Chesapeake Bay By Karen C. Rice, Mark R. Bennett, and Jian Shen Prepared in cooperation with the City of Newport News Open-File Report 2011–1191 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2011 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Rice, K.C., Bennett, M.R., and Shen, Jian, 2011, Simulated changes in salinity in the York and Chickahominy Rivers from projected sea-level rise in Chesapeake Bay: U.S. -

Hydrogeologic Framework of the Shallow Aquifer System of York County, Virginia

Hydrogeologic Framework of the Shallow Aquifer System of York County, Virginia By Alien R. Brockman and Donna L. Richardson U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 92-4111 Prepared in cooperation with the YORK COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES, and VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY Richmond, Virginia 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director First Printing March1992 Second Printing (with corrections) January 1995 For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Earth Science Information Center 3600 West Broad Street Open-File Reports Section Room 606 60x25286, MS 517 Richmond, VA 23230 Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 CONTENTS Page Abstract............................................................................... 1 Introduction........................................................................... 1 Purpose and scope.................................................................. 2 Previous investigations.............................................................. 2 Approach.......................................................................... 3 Acknowledgments.................................................................. 3 Description of study area................................................................ 3 Location and physiographic setting ................................................... 4 Geology.......................................................................... -

Itinerary: Jamestown , Williamsburg , Yorktown

Itinerary: Jamestown , Williamsburg , Yorktown Take the free shuttle of Jamestown which will lead you to Historic Jamestown, Jamestown Glasshouse and Jamestown Settlement. The shuttle of Yorktown will bring you to Yorktown Battlefield and Yorktown Victory Center. (Shuttles operate seasonally April-October) Day 1: Colonial Williamsburg Offers you a variety of activities making you discover the way lived the inhabitants of the capital of the Virginia during the 18th century. You will find more than 30 reconstructions of colonial houses, governmental buildings and craftsmen's workshops there exposing tools and techniques of colonial period. The historic district is a full of life village presenting also more than about twenty shops, restaurants and hotels. Hours: 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. 2009 Rates: Adults $34.95 $44.95* Youth (ages 6-17) $17.45 $22.45* Senior (age 62 and above) $34.45 $40.45* Possibility of on-line purchase *includes governor’s palace tour and two consecutive days’ access Contact: http://www.history.org/ P. O. Box 1776-Williamsburg, VA 23187-1776 ▪ Phone: (757) 229-1000 Day 2: Bush Gardens USA Voted the world’s “Most Beautiful Theme Park” for 18 consecutive years, Busch Gardens combines 17th century charm with 21st century technology to create the ultimate family experience. Situated on 100 action-packed acres, Busch Gardens boasts more than 50 thrilling rides and attractions, nine main stage shows, a wide variety of award-winning cuisine and world-class shops. He constitutes an ideal park to spend pleasant moments in family or with friends Hours: 9:00 a.m. -

Chickahominy Riverfront Park Raw Water Intake and Water Treatment Facility Public Information Meeting July 25, 2016 PERMITS THAT DETERMINE AVAILABLE WATER CAPACITY

Chickahominy Riverfront Park Raw Water Intake and Water Treatment Facility Public Information Meeting July 25, 2016 PERMITS THAT DETERMINE AVAILABLE WATER CAPACITY GROUNDWATER WATERWORKS OPERATION WITHDRAWAL PERMIT PERMIT ANNUAL AVG = 8.8 MGD MAX = 9.973 MGD MAX MONTH = 11.8 MGD 2 Why do we need a new water supply? Eastern Virginia GroundwaterEastern Virginia Groundwater Management AreaManagement Area • Declining groundwater levels • Advancing salt water intrusion • Land subsidence JCSA Permitted Groundwater Withdrawal Reduction (DEQ Proposal: 8.8 mgd reduced to 3.8-4.0 mgd) 3 JCSA Water Supply . Existing Supply DEQ VDH Capacity Production Facility Annual Withdrawal (mgd) (mgd) Five Forks WTP 5.9 5.000 7 Well Locations 2.9 4.973 • Owens-Illinois • Stonehouse • Ford’s Colony • Kristiansands • The Pottery • Canterbury Hills • Ewell Hall and Olde Towne Road TOTAL 8.8 9.973 . Potential Future Water Supply Newport News Waterworks (NNWW) Purchase Agreement = 2 mgd (drought condition)* *JCSA infrastructure improvements required for delivery. 4 Average water demand is projected to increase. 5 Future demand will exceed existing permitted capacity. Average Day Demand Maximum Day Demand 6 Reduction in DEQ permitted groundwater withdrawal to 4.0 mgd will result in immediate deficit. Current DEQ Groundwater Withdrawal Reduced DEQ Groundwater Withdrawal IMMEDIATE DEFICIT 7 Reduction in DEQ permitted groundwater withdrawal to 4.0 mgd impacts VDH permitted maximum capacity Current DEQ Groundwater Withdrawal Reduced DEQ Groundwater Withdrawal IMMEDIATE DEFICIT 8 Water Supply Alternatives No Action Water Conservation Only Alternative Water Supply with Water Conservation 9 Water Conservation Measures – Already in Effect . Water conservation and drought management program . Install low water use fixtures – Building Code . -

Pocahontas Revealed

Original broadcast: May 8, 2007 BEFORE WATCHING Pocahontas Revealed 1 Ask students to work in groups to make a time line of major events from the initial discovery of America by Paleo-Indians up PROGRAM OVERVIEW until 1607 when the Jamestown NOVA brings together ancient artisans, Colony was founded. Who were the main inhabitants of America when historians, and archeologists to provide a Jamestown was settled? fresh look at the myth of Pocahontas. 2 In this program, scientists are The program: discovering a new perspective on • reviews how Virginia’s Jamestown became an historic event. Organize students into groups and have the first permanent English settlement in each group choose an event in U.S. the New World in 1607. history to investigate from different • recounts that Captain John Smith and other English settlers came perspectives. (Some events to America to hunt for exploitable resources. students may want to explore are • notes that the English settlers planned to trade goods for food with the Boston Tea Party, the Battle of the Alamo, the Battle of the Indians* rather than grow their own. Gettysburg, or the desegregation • recounts how Smith came to be captured by the Indians and was of Little Rock Central High.) Ask eventually taken to their political center, Werowocomoco. each group to present its findings. • presents Smith’s recollection of the historical meeting—written 17 years after it occurred—that took place between him and Chief Powhatan in which Pocahontas reportedly saved his life. AFTER WATCHING • traces how archeologists determined where the Werowocomoco site was and documents key findings indicating the location of the 1 Many of the James Fort colonists died and the community was on longhouse in which the fabled meeting is said to have taken place.