Claudia Macedo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Report Clinical Report of a 17Q12 Microdeletion with Additionally Unreported Clinical Features

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Genetics Volume 2014, Article ID 264947, 6 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/264947 Case Report Clinical Report of a 17q12 Microdeletion with Additionally Unreported Clinical Features Jennifer L. Roberts,1 Stephanie K. Gandomi,2 Melissa Parra,2 Ira Lu,2 Chia-Ling Gau,2 Majed Dasouki,1,3 and Merlin G. Butler1 1 The University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA 2 Ambry Genetics, Aliso Viejo, CA 92656, USA 3 King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Riyadh 12713, Saudi Arabia Correspondence should be addressed to Stephanie K. Gandomi; [email protected] Received 18 March 2014; Revised 13 May 2014; Accepted 14 May 2014; Published 2 June 2014 Academic Editor: Philip D. Cotter Copyright © 2014 Jennifer L. Roberts et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Copy number variations involving the 17q12 region have been associated with developmental and speech delay, autism, aggression, self-injury, biting and hitting, oppositional defiance, inappropriate language, and auditory hallucinations. We present a tall- appearing 17-year-old boy with marfanoid habitus, hypermobile joints, mild scoliosis, pectus deformity, widely spaced nipples, pes cavus, autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, and psychiatric manifestations including physical and verbal aggression, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, and oppositional defiance. An echocardiogram showed borderline increased aortic root size. An abdominal ultrasound revealed a small pancreas, mild splenomegaly with a 1.3 cm accessory splenule, and normal kidneys and liver. -

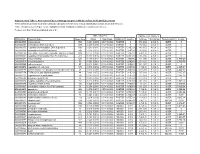

Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B Activin a Receptor, Type IB

Table S1. Kinase clones included in human kinase cDNA library for yeast two-hybrid screening Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B activin A receptor, type IB ADCK2 aarF domain containing kinase 2 ADCK4 aarF domain containing kinase 4 AGK multiple substrate lipid kinase;MULK AK1 adenylate kinase 1 AK3 adenylate kinase 3 like 1 AK3L1 adenylate kinase 3 ALDH18A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family, member A1;ALDH18A1 ALK anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Ki-1) ALPK1 alpha-kinase 1 ALPK2 alpha-kinase 2 AMHR2 anti-Mullerian hormone receptor, type II ARAF v-raf murine sarcoma 3611 viral oncogene homolog 1 ARSG arylsulfatase G;ARSG AURKB aurora kinase B AURKC aurora kinase C BCKDK branched chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase BMPR1A bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type IA BMPR2 bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type II (serine/threonine kinase) BRAF v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 BRD3 bromodomain containing 3 BRD4 bromodomain containing 4 BTK Bruton agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase BUB1 BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog (yeast) BUB1B BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog beta (yeast) C9orf98 chromosome 9 open reading frame 98;C9orf98 CABC1 chaperone, ABC1 activity of bc1 complex like (S. pombe) CALM1 calmodulin 1 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM2 calmodulin 2 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM3 calmodulin 3 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CAMK1 calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I CAMK2A calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM kinase) II alpha CAMK2B calcium/calmodulin-dependent -

The Title of the Article

Mechanism-Anchored Profiling Derived from Epigenetic Networks Predicts Outcome in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Xinan Yang, PhD1, Yong Huang, MD1, James L Chen, MD1, Jianming Xie, MSc2, Xiao Sun, PhD2, Yves A Lussier, MD1,3,4§ 1Center for Biomedical Informatics and Section of Genetic Medicine, Department of Medicine, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637 USA 2State Key Laboratory of Bioelectronics, Southeast University, 210096 Nanjing, P.R.China 3The University of Chicago Cancer Research Center, and The Ludwig Center for Metastasis Research, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637 USA 4The Institute for Genomics and Systems Biology, and the Computational Institute, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637 USA §Corresponding author Email addresses: XY: [email protected] YH: [email protected] JC: [email protected] JX: [email protected] XS: [email protected] YL: [email protected] - 1 - Abstract Background Current outcome predictors based on “molecular profiling” rely on gene lists selected without consideration for their molecular mechanisms. This study was designed to demonstrate that we could learn about genes related to a specific mechanism and further use this knowledge to predict outcome in patients – a paradigm shift towards accurate “mechanism-anchored profiling”. We propose a novel algorithm, PGnet, which predicts a tripartite mechanism-anchored network associated to epigenetic regulation consisting of phenotypes, genes and mechanisms. Genes termed as GEMs in this network meet all of the following criteria: (i) they are co-expressed with genes known to be involved in the biological mechanism of interest, (ii) they are also differentially expressed between distinct phenotypes relevant to the study, and (iii) as a biomodule, genes correlate with both the mechanism and the phenotype. -

Bioinformatic Analyses of Integral Membrane Transport Proteins Encoded Within the Genome of the Planctomycetes Species, Rhodopirellula Baltica

UC San Diego UC San Diego Previously Published Works Title Bioinformatic analyses of integral membrane transport proteins encoded within the genome of the planctomycetes species, Rhodopirellula baltica. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0f85q1z7 Journal Biochimica et biophysica acta, 1838(1 Pt B) ISSN 0006-3002 Authors Paparoditis, Philipp Västermark, Ake Le, Andrew J et al. Publication Date 2014 DOI 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.08.007 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1838 (2014) 193–215 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biochimica et Biophysica Acta journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bbamem Bioinformatic analyses of integral membrane transport proteins encoded within the genome of the planctomycetes species, Rhodopirellula baltica Philipp Paparoditis a, Åke Västermark a,AndrewJ.Lea, John A. Fuerst b, Milton H. Saier Jr. a,⁎ a Department of Molecular Biology, Division of Biological Sciences, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA, 92093–0116, USA b School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, 9072, Australia article info abstract Article history: Rhodopirellula baltica (R. baltica) is a Planctomycete, known to have intracellular membranes. Because of its un- Received 12 April 2013 usual cell structure and ecological significance, we have conducted comprehensive analyses of its transmembrane Received in revised form 8 August 2013 transport proteins. The complete proteome of R. baltica was screened against the Transporter Classification Data- Accepted 9 August 2013 base (TCDB) to identify recognizable integral membrane transport proteins. 342 proteins were identified with a Available online 19 August 2013 high degree of confidence, and these fell into several different classes. -

Transcriptional Regulation of RKIP in Prostate Cancer Progression

Health Science Campus FINAL APPROVAL OF DISSERTATION Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Sciences Transcriptional Regulation of RKIP in Prostate Cancer Progression Submitted by: Sandra Marie Beach In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Sciences Examination Committee Major Advisor: Kam Yeung, Ph.D. Academic William Maltese, Ph.D. Advisory Committee: Sonia Najjar, Ph.D. Han-Fei Ding, M.D., Ph.D. Manohar Ratnam, Ph.D. Senior Associate Dean College of Graduate Studies Michael S. Bisesi, Ph.D. Date of Defense: May 16, 2007 Transcriptional Regulation of RKIP in Prostate Cancer Progression Sandra Beach University of Toledo ACKNOWLDEGMENTS I thank my major advisor, Dr. Kam Yeung, for the opportunity to pursue my degree in his laboratory. I am also indebted to my advisory committee members past and present, Drs. Sonia Najjar, Han-Fei Ding, Manohar Ratnam, James Trempe, and Douglas Pittman for generously and judiciously guiding my studies and sharing reagents and equipment. I owe extended thanks to Dr. William Maltese as a committee member and chairman of my department for supporting my degree progress. The entire Department of Biochemistry and Cancer Biology has been most kind and helpful to me. Drs. Roy Collaco and Hong-Juan Cui have shared their excellent technical and practical advice with me throughout my studies. I thank members of the Yeung laboratory, Dr. Sungdae Park, Hui Hui Tang, Miranda Yeung for their support and collegiality. The data mining studies herein would not have been possible without the helpful advice of Dr. Robert Trumbly. I am also grateful for the exceptional assistance and shared microarray data of Dr. -

Download The

PROBING THE INTERACTION OF ASPERGILLUS FUMIGATUS CONIDIA AND HUMAN AIRWAY EPITHELIAL CELLS BY TRANSCRIPTIONAL PROFILING IN BOTH SPECIES by POL GOMEZ B.Sc., The University of British Columbia, 2002 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Experimental Medicine) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) January 2010 © Pol Gomez, 2010 ABSTRACT The cells of the airway epithelium play critical roles in host defense to inhaled irritants, and in asthma pathogenesis. These cells are constantly exposed to environmental factors, including the conidia of the ubiquitous mould Aspergillus fumigatus, which are small enough to reach the alveoli. A. fumigatus is associated with a spectrum of diseases ranging from asthma and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis to aspergilloma and invasive aspergillosis. Airway epithelial cells have been shown to internalize A. fumigatus conidia in vitro, but the implications of this process for pathogenesis remain unclear. We have developed a cell culture model for this interaction using the human bronchial epithelium cell line 16HBE and a transgenic A. fumigatus strain expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP). Immunofluorescent staining and nystatin protection assays indicated that cells internalized upwards of 50% of bound conidia. Using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), cells directly interacting with conidia and cells not associated with any conidia were sorted into separate samples, with an overall accuracy of 75%. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling using microarrays revealed significant responses of 16HBE cells and conidia to each other. Significant changes in gene expression were identified between cells and conidia incubated alone versus together, as well as between GFP positive and negative sorted cells. -

Nematostella Genome

Sea anemone genome reveals the gene repertoire and genomic organization of the eumetazoan ancestor Nicholas H. Putnam[1], Mansi Srivastava[2], Uffe Hellsten[1], Bill Dirks[2], Jarrod Chapman[1], Asaf Salamov[1], Astrid Terry[1], Harris Shapiro[1], Erika Lindquist[1], Vladimir V. Kapitonov[3], Jerzy Jurka[3], Grigory Genikhovich[4], Igor Grigoriev[1], JGI Sequencing Team[1], Robert E. Steele[5], John Finnerty[6], Ulrich Technau[4], Mark Q. Martindale[7], Daniel S. Rokhsar[1,2] [1] Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, Walnut Creek, CA 94598 [2] Center for Integrative Genomics and Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of California, Berkeley CA 94720 [3] Genetic Information Research Institute, 1925 Landings Drive, Mountain View, CA 94043 [4] Sars International Centre for Marine Molecular Biology, University of Bergen, Thormoeøhlensgt 55; 5008, Bergen, Norway [5] Department of Biological Chemistry and the Developmental Biology Center, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697 [6] Department of Biology, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215 [7] Kewalo Marine Laboratory, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96813 Abstract Sea anemones are seemingly primitive animals that, along with corals, jellyfish, and hydras, constitute the Cnidaria, the oldest eumetazoan phylum. Here we report a comparative analysis of the draft genome of an emerging cnidarian model, the starlet anemone Nematostella vectensis. The anemone genome is surprisingly complex, with a gene repertoire, exon-intron structure, and large-scale gene linkage more similar to vertebrates than to flies or nematodes. These results imply that the genome of the eumetazoan ancestor was similarly complex, and that fly and nematode genomes have been modified via sequence divergence, gene and intron loss, and genomic rearrangement. -

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

Knowledge Management Enviroments for High Throughput Biology

Knowledge Management Enviroments for High Throughput Biology Abhey Shah A Thesis submitted for the degree of MPhil Biology Department University of York September 2007 Abstract With the growing complexity and scale of data sets in computational biology and chemoin- formatics, there is a need for novel knowledge processing tools and platforms. This thesis describes a newly developed knowledge processing platform that is different in its emphasis on architecture, flexibility, builtin facilities for datamining and easy cross platform usage. There exist thousands of bioinformatics and chemoinformatics databases, that are stored in many different forms with different access methods, this is a reflection of the range of data structures that make up complex biological and chemical data. Starting from a theoretical ba- sis, FCA (Formal Concept Analysis) an applied branch of lattice theory, is used in this thesis to develop a file system that automatically structures itself by it’s contents. The procedure of extracting concepts from data sets is examined. The system also finds appropriate labels for the discovered concepts by extracting data from ontological databases. A novel method for scaling non-binary data for use with the system is developed. Finally the future of integrative systems biology is discussed in the context of efficiently closed causal systems. Contents 1 Motivations and goals of the thesis 11 1.1 Conceptual frameworks . 11 1.2 Biological foundations . 12 1.2.1 Gene expression data . 13 1.2.2 Ontology . 14 1.3 Knowledge based computational environments . 15 1.3.1 Interfaces . 16 1.3.2 Databases and the character of biological data . -

Aneuploidy: Using Genetic Instability to Preserve a Haploid Genome?

Health Science Campus FINAL APPROVAL OF DISSERTATION Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science (Cancer Biology) Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Submitted by: Ramona Ramdath In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science Examination Committee Signature/Date Major Advisor: David Allison, M.D., Ph.D. Academic James Trempe, Ph.D. Advisory Committee: David Giovanucci, Ph.D. Randall Ruch, Ph.D. Ronald Mellgren, Ph.D. Senior Associate Dean College of Graduate Studies Michael S. Bisesi, Ph.D. Date of Defense: April 10, 2009 Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Ramona Ramdath University of Toledo, Health Science Campus 2009 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my grandfather who died of lung cancer two years ago, but who always instilled in us the value and importance of education. And to my mom and sister, both of whom have been pillars of support and stimulating conversations. To my sister, Rehanna, especially- I hope this inspires you to achieve all that you want to in life, academically and otherwise. ii Acknowledgements As we go through these academic journeys, there are so many along the way that make an impact not only on our work, but on our lives as well, and I would like to say a heartfelt thank you to all of those people: My Committee members- Dr. James Trempe, Dr. David Giovanucchi, Dr. Ronald Mellgren and Dr. Randall Ruch for their guidance, suggestions, support and confidence in me. My major advisor- Dr. David Allison, for his constructive criticism and positive reinforcement. -

Literature Mining Sustains and Enhances Knowledge Discovery from Omic Studies

LITERATURE MINING SUSTAINS AND ENHANCES KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM OMIC STUDIES by Rick Matthew Jordan B.S. Biology, University of Pittsburgh, 1996 M.S. Molecular Biology/Biotechnology, East Carolina University, 2001 M.S. Biomedical Informatics, University of Pittsburgh, 2005 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Medicine in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF MEDICINE This dissertation was presented by Rick Matthew Jordan It was defended on December 2, 2015 and approved by Shyam Visweswaran, M.D., Ph.D., Associate Professor Rebecca Jacobson, M.D., M.S., Professor Songjian Lu, Ph.D., Assistant Professor Dissertation Advisor: Vanathi Gopalakrishnan, Ph.D., Associate Professor ii Copyright © by Rick Matthew Jordan 2016 iii LITERATURE MINING SUSTAINS AND ENHANCES KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM OMIC STUDIES Rick Matthew Jordan, M.S. University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Genomic, proteomic and other experimentally generated data from studies of biological systems aiming to discover disease biomarkers are currently analyzed without sufficient supporting evidence from the literature due to complexities associated with automated processing. Extracting prior knowledge about markers associated with biological sample types and disease states from the literature is tedious, and little research has been performed to understand how to use this knowledge to inform the generation of classification models from ‘omic’ data. Using pathway analysis methods to better understand the underlying biology of complex diseases such as breast and lung cancers is state-of-the-art. However, the problem of how to combine literature- mining evidence with pathway analysis evidence is an open problem in biomedical informatics research. -

Table S4. Trophoblast Differentiation-Associated Genes

Table S4. Trophoblast differentiation-associated genes Gene Stem Chromosomal Affymetrix ID Gene Title Symbol Ave Dif Ave GenBank Location dif/ stem t-test 1390511_at LOC308394 Cgm4 10 1863 BI285801 1 193.51 0.006 1378534_at similar to brain carcinoembryonic antigen LOC308394 10 1746 NM_001025679 1q21 183.10 0.001 1388433_at keratin complex 1, acidic, gene 19 Krt1-19 53 7958 NM_199498 10q32.1 149.07 0.022 1369029_at phospholipid scramblase 1 Plscr1 20 2050 NM_057194 8q31 101.12 0.028 1389856_at carcinoembryonic antigen gene family 4 Cgm4 57 5073 NM_012525 1q21 89.73 0.001 carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell 1368996_at adhesion molecule 3 Ceacam3 202 17879 NM_012702 1q21 88.71 0.001 1392832_at similar to angiopoietin-like 1 LOC684489 17 1398 XM_001068284 --- 83.66 0.001 1377666_at choline dehydrogenase Chdh 26 1571 NM_198731 16p16 60.59 0.003 cytochrome P450, family 11, subfamily a, 1368468_at polypeptide 1 Cyp11a1 196 9216 NM_017286 8q24 47.11 0.000 1376934_x_at similar to brain carcinoembryonic antigen Cgm4 53 2146 BI285801 1 40.22 0.000 stimulated by retinoic acid gene 6 homolog 1390525_a_at (mouse) Stra6 28 1037 NM_001029924 8q24 37.44 0.001 1382690_at carcinoembryonic antigen gene family 4 Cgm4 81 2729 NM_012525 1q21 33.86 0.001 1367809_at prolactin family 4, subfamily a, member 1 Prl4a1 683 22573 NM_017036 17p11 33.05 0.004 calcium channel, voltage-dependent, L type, 1383458_at alpha 1D subunit Cacna1d 26 802 BF403759 16 30.89 0.001 1370852_at spleen protein 1 precursor LOC171573 692 20968 NM_138537 8q21 30.29 0.003 1376036_at transporter