Studia Podlaskie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transnational Influences on Women's Arguments

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Undergraduate Honors Theses 2020-03-20 “Women Thus Educated”: Transnational Influences on omenW ’s Arguments for Female Education in Seventeenth-Century England Miranda Jessop Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studentpub_uht BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Jessop, Miranda, "“Women Thus Educated”: Transnational Influences on omenW ’s Arguments for Female Education in Seventeenth-Century England" (2020). Undergraduate Honors Theses. 119. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studentpub_uht/119 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Honors Thesis “WOMEN THUS EDUCATED”: TRANSNATIONAL INFLUENCES ON WOMEN’S ARGUMENTS FOR FEMALE EDUCATION IN SEVENTEETH-CENTURY ENGLAND by Miranda Jessop Submitted to Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of graduation requirements for University Honors History Department Brigham Young University April 2020 Advisor: Rebecca de Schweinitz Honors Coordinator: Shawn Miller ii ABSTRACT “WOMEN THUS EDUCATED”: TRANSNATIONAL INFLUENCES ON WOMEN’S ARGUMENTS FOR FEMALE EDUCATION IN SEVENTEETH-CENTURY ENGLAND Miranda Jessop History Department Bachelor of Arts This thesis explores the intellectual history of proto-feminist thought in early modern England and seeks to better understand the transnational elements of and influences on proto- feminist theorists’ arguments in favor of women’s education in the late seventeenth century. A close reading of Bathsua Makin and Anna Maria Van Schurman’s essays in relation to one another, and within their social and historical context, reveals the importance of ideas of religion and social order, especially class, in understanding and justifying women’s education. -

Anna Maria Van Schurman

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen English, 1593 - 1661 Anna Maria van Schurman 1657 oil on panel overall: 31 x 24.4 cm (12 3/16 x 9 5/8 in.) Inscription: center left, below the cathedral, in the portrait medallion: Cornelius Ionson / Van Ceulen / fecit / 1657 Gift of Joseph F. McCrindle 2002.35.1 ENTRY This monochrome panel painting, or grisaille, [1] made in preparation for an engraving by Cornelis van Dalen the Younger (Dutch, 1638 - 1664) [fig. 1], depicts a learned lady of international renown: Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678). [2] Van Schurman was born in Cologne on November 5, 1607, to Frederik van Schurman and Eva von Harff, both of whom came from wealthy and noble Protestant families. [3] By 1615 Anna’s parents had settled in Utrecht, where she soon demonstrated remarkable talent in embroidery, calligraphy, and the making of intricate paper cuttings. In the 1630s she took lessons in drawing and engraving from Magdalena van de Passe (Dutch, 1600 - 1638), daughter of the engraver Crispijn van de Passe I (Dutch, c. 1565 - 1637). Van Schurman began making small portraits, including self-portraits, in a variety of mediums, among them pastels and oils, and small sculptures made of boxwood or wax. In recognition of her artistic abilities, the Saint Luke’s Guild of Utrecht gave her an honorary membership in 1643. [4] Van Schurman was renowned even more for her intellectual concerns than for her artistic accomplishments. Referred to as the Utrecht “Minerva,” she exchanged poems and corresponded with some of the greatest minds of the day, including Anna Maria van Schurman 1 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), René Descartes (1596–1650), and Jacob Cats (1577–1660). -

•Œintimacy With

Please HONOR the copyright of these documents by not retransmitting or making any additional copies in any form (Except for private personal use). We appreciate your respectful cooperation. ___________________________ Theological Research Exchange Network (TREN) P.O. Box 30183 Portland, Oregon 97294 USA Website: www.tren.com E-mail: [email protected] Phone# 1-800-334-8736 ___________________________ Ministry Focus Paper Approval Sheet This ministry focus paper entitled “INTIMACY WITH GOD: PRACTICING THE PRESENCE OF GOD”: A MASTER’S LEVEL COURSE Written by Patricia H. West and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry has been accepted by the Faculty of Fuller Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned readers: _____________________________________ Tom Schwanda _____________________________________ Kurt Fredrickson Date Received: August 30, 2012 “INTIMACY WITH GOD: PRACTICING THE PRESENCE OF GOD”: A MASTER’S LEVEL COURSE A MINISTRY FOCUS PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY FULLER THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY PATRICIA H. WEST AUGUST 2012 ABSTRACT “Intimacy with God: Practicing the Presence of God”: A Master’s Level Course Patricia H. West Doctor of Ministry School of Theology, Fuller Theological Seminary 2012 The purpose of this study is to establish and address the need for a graduate course, “Intimacy with God: Practicing the Presence of God,” among seminary students that includes experiential learning in regards to growing a deeper relationship with God. This project argues that scriptural knowledge alone cannot fulfill students’ needs for the intimacy they seek with God. -

Warning Against the Pietists: the World of Wilhelmus À Brakel

chapter 12 Warning against the Pietists: The World of Wilhelmus à Brakel Fred van Lieburg Abstract In 1700 the Reformed minister Wilhelmus à Brakel published a voluminous compen- dium of theology in the vernacular for a Dutch lay audience. The book immediately proved a best-seller. Still in print, it remains highly valued as a work of devotional lit- erature among Dutch neo-calvinists. In the third edition (1707) the author added a new chapter, delineating Reformed orthodoxy against various forms of ‘natural’ reli- gion. Brakel appears to have been very apprehensive of the developments in German Pietism. The genesis and content of the new chapter, warning his audience ‘against Pietists, Quietists, and … Spiritless Religion Under the Guise of Spirituality’ show how a prominent minister like Brakel found himself moving the frontiers between Reformed orthodoxy and rationalism, reacting against some of the pietisms of his day, and evolving towards a ‘new Protestantism.’ 1 Between Reason and Piety At the turn of the eighteenth century, Wilhelmus à Brakel (1635–1711), ‘Minister of the Divine Word’ in Rotterdam, published his Λογικη λατρεια, dat is Redelyke godts-dienst (Logikè Latreia, that is Reasonable Religion). The author could not have predicted that his voluminous work would become and remain a best- seller.1 Although the title might suggest a commitment to contemporary ratio- nalism, in reality it referred to the apostolic vocabulary of earliest Christianity (Paul’s letter to the Romans, 12,1). In ecclesiastical historiography Brakel is associated with post-Reformation confessionalism or even early Pietism. As a 1 Wilhelmus à Brakel, Logikè latreia, dat is Redelyke godts-dienst. -

PROVISIONAL PROGRAM HNA Conference 2022

PROVISIONAL PROGRAM HNA Conference 2022 Amsterdam and The Hague, Netherlands HNA CONFERENCE 2022 Amsterdam and The Hague 2-4 June 2022 Program committee: Stijn Bussels, Leiden University (chair) Edwin Buijsen, Mauritshuis Suzanne Laemers, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History Judith Noorman, University of Amsterdam Gabri van Tussenbroek, University of Amsterdam | City of Amsterdam Abbie Vandivere, Mauritshuis and University of Amsterdam KEYNOTE LECTURES ClauDia Swan, Washington University A Taste for Piracy in the Dutch Republic 1 The global baroque world was a world of goods. Transoceanic trade routes compounded travel over land for commercial gain, and the distribution of wares took on global dimensions. Precious metals, spices, textiles, and, later, slaves were among the myriad commodities transported from west to east and in some cases back again. Taste followed trade—or so the story tends to be told. This lecture addresses the traffic in global goods in the Dutch world from a different perspective—piracy. “A Taste for Piracy in the Dutch Republic” will present and explore exemplary narratives of piracy and their impact and, more broadly, the contingencies of consumption and taste- making as the result of politically charged violence. Inspired by recent scholarship on ships, shipping, maritime pictures, and piracy this lecture offers a new lens onto the culture of piracy as well as the material goods obtained by piracy, and how their capture informed new patterns of consumption in the Dutch Republic. Jan Blanc, University of Geneva Dutch Seventeenth Century or Dutch Golden Age? Words, concepts and ideology Historians of seventeenth-century Dutch art have long been accustomed to studying not only works of art and artists, but also archives and textual sources. -

Class 7: Elisabeth of Bohemia (1618-80) (From Women

Class 7: Elisabeth of Bohemia (1618-80) works’ (ibid.). Today she is one of the best-known early modern women philosophers—despite the fact (from Women Philosophers of the Seven- that she left no systematic philosophical writings of her teenth Century by Jacqueline Broad) own, and that her key philosophical contributions are in the form of letters. Other than her correspondence Recent commentators have raised methodological with Descartes, there are only a handful of letters from questions about how women philosophers of the past Elisabeth to other male thinkers, such as Nicolas can be incorporated into the philosophical canon.1 Malebranche,3 Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz,4 and the One common and useful method of inclusion is to Quaker Robert Barclay (1648-90).5 show that these women participated in the great intellectual debates of their time, and that they were Nevertheless, historians of philosophy agree that perceptive critics of their famous male contempor- there is also something limiting about the ‘add women aries. This is the usual approach taken to the philo- and stir’ approach to women philosophers of the past. sophical writings of Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, In the case of Elisabeth, this ‘assimilation’ method has the friend and correspondent of René Descartes. On meant that until recently the study of her own the basis of her famous exchange of letters with philosophical themes remained incomplete. Commen- Descartes (from 1643 to 1649), Elisabeth is celebrated tators examined the philosophical import of Elisa- as one of the first writers to raise the problem of mind– beth’s objections to Descartes, and acknowledged the impact that her queries had on Descartes’ subsequent body interaction for Cartesian dualism. -

The Rhetoric of Self-Denial in the Mystical Theologies of Anna Maria Van Schurman and Madame Jeanne Guyon Franciscanum

Franciscanum. Revista de las ciencias del espíritu ISSN: 0120-1468 [email protected] Universidad de San Buenaventura Colombia Lee, Bo Karen Sacrifice and Desire: The Rhetoric of Self-Denial in the Mystical Theologies of Anna Maria van Schurman and Madame Jeanne Guyon Franciscanum. Revista de las ciencias del espíritu, vol. LI, núm. 151, enero-junio, 2009, pp. 207-239 Universidad de San Buenaventura Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=343529805009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 207 Sacrifice and Desire: The Rhetoric of Self-Denial in the Mystical Theologies of Anna Maria van Schurman and Madame Jeanne Guyon Bo Karen Lee* Resumen Anna Maria van Schurman (1607-1678), calvinista holandesa, y Madame Jeanne Guyon (1648-1717), católica francesa, desafiaron la organización religiosa en la Europa del siglo XVII y transgredieron las fronteras institucionales en medio del conflicto religioso. ¿Qué tenían en común estas dos mujeres, a pesar de la controversia teoló- gica entre católicos y calvinistas? Tanto van Schurman como Madame Guyon argumentaban que “el fin último de la humanidad” es “gozar a Dios”, y su preocupación principal era cómo lograr la unión con el objeto de deseo y disfrutar ese summum bonum. Asimismo, las dos consideraban que la unión con Dios es posible, en esta vida, negán- dose a sí mismo/a o autodestrucción y las dos encontraban placer en esta autonegación, integrando una a teología del sacrificio con una teología del deseo y del placer. -

JOHN HUGO and an AMERICAN CATHOLIC THEOLOGY of NATURE and GRACE Dissertation Submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences of Th

JOHN HUGO AND AN AMERICAN CATHOLIC THEOLOGY OF NATURE AND GRACE Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Benjamin T. Peters UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio May, 2011 JOHN HUGO AND AN AMERICAN CATHOLIC THEOLOGY OF NATURE AND GRACE Name: Peters, Benjamin Approved by: ________________________________________________________________ William Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _______________________________________________________________ Dennis Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ______________________________________________________________ Kelly Johnson, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _____________________________________________________________ Sandra Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _____________________________________________________________ Michael Baxter, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _____________________________________________________________ Sandra Yocum, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Benjamin Tyler Peters All right reserved 2011 iii ABSTRACT JOHN HUGO AND AN AMERICAN CATHOLIC THEOLOGY OF NATURE AND GRACE Name: Peters, Benjamin Tyler University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. William L. Portier This dissertation examines the theological work of John Hugo by looking at its roots within the history of Ignatian spirituality, as well as within various nature-grace debates in Christian history. It also attempts to situate Hugo within the historical context of early twentieth-century Catholicism and America, particularly the period surrounding the Second World War. John Hugo (1911-1985) was a priest from Pittsburgh who is perhaps best known as Dorothy Day‟s spiritual director and leader of “the retreat” she memorialized in The Long Loneliness. Throughout much of American Catholic scholarship, Hugo‟s theology has been depicted as rigorist and even labeled as Jansenist, yet it was embraced by and had a great influence upon Day and many others. -

Anna Maria Van Schurman and Antoinette Bourignon As Contrasting Examples

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Groningen Digital Archive Gender, genre and authority in seventeenth-century religious writing: Anna Maria van Schurman and Antoinette Bourignon as contrasting examples Mirjam de Baar (University of Groningen) Publishing entails publicity or at least an intervention in the public sphere. Wo- men in the early modern period, however, were not allowed to speak in public. In accordance with the admonitions of the apostle Paul (I Cor. 14:34 and I Tim. 2:11-12) they were meant to observe silence. A woman who wanted to publish her thoughts was suspected of being willing to make her body available as well. This injunction to female silence was so strong that the majority of women who did publish felt the need to justify their audacity. In addition to these cultural admonitions advocating female silence, Merry Wiesner, author of Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe , mentions two other barriers that prevented women in early modern Europe from publishing: their relative lack of educational opportunities and economic factors. 1 These barriers might explain why women throughout the early modern period repre- sented only a tiny share of the total amount of printed material, though their share did increase during this period. Patricia Crawford has shown that in England between 1600 and 1640 publications by women accounted for only 0.5 percent of the total, increasing in the next six decades to 1.2 percent. 2 The majority of early modern women’s published works were religious, particularly in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when the vast majority of all publications were religious. -

Dutch Women in New Netherland and New York in the Seventeenth Century

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2001 Dutch women in New Netherland and New York in the seventeenth century Michael Eugene Gherke West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Gherke, Michael Eugene, "Dutch women in New Netherland and New York in the seventeenth century" (2001). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 1430. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/1430 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dutch Women in New Netherland and New York in the Seventeenth Century Michael E. Gherke Dissertation submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Mary Lou Lustig, Ph.D., chair Jack Hammersmith, Ph.D. Matthew Vester, Ph.D. Caroline Litzenberger, Ph.D. Martha Shattuck, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 2001 copyright © Gherke, Michael E. -

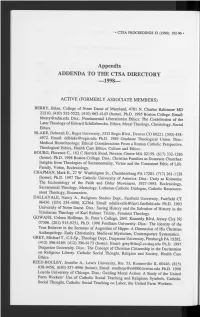

Appendix ADDENDA to the CTSA DIRECTORY —1998—

• CTSA PROCEEDINGS 53 (1998): 192-96 • Appendix ADDENDA TO THE CTSA DIRECTORY —1998— ACTIVE (FORMERLY ASSOCIATE MEMBERS) BERRY, Brian, College of Notre Dame of Maryland, 4701 N. Charles Baltimore MD 21210. (410) 532-5522; (410) 663-4143 (home). Ph.D. 1995 Boston College. Email: [email protected] Diss.: Fundamental Liberationist Ethics: The Contribution of the Later Theology of Edward Schillebeeckx. Ethics, Moral Theology, Christology, Social Ethics. BLAKE, Deborah D., Regis University, 3333 Regis Blvd., Denver CO 80221. (303) 458- 4972. Email: [email protected] Ph.D. 1989 Graduate Theological Union. Diss.: Medical Biotechnology: Ethical Considerations From a Roman Catholic Perspective. Theological Ethics, Health Care Ethics, Culture and Ethics. BOURG, Florence C., 162 C Herrick Road, Newton Centre MA 02159. (617) 332-1286 (home). Ph.D. 1998 Boston College. Diss.: Christian Families as Domestic Churches: Insights from Theologies of Sacramentality, Virtue and the Consistent Ethic of Life. Family, Virtue, Ecclesiology. CHAPMAN, Mark E., 27 W. Washington St., Chambersburg PA 17201. (717) 261-1128 (home); Ph.D. 1997 The Catholic University of America. Diss.: Unity as Koinonia: The Ecclesiology of the Faith and Order Movement, 1927-1993. Ecclesiology, Sacramental Theology, Mariology, Lutheran-Catholic Dialogue, Catholic Ressource- ment Theology, Ecumenism. DALLAVALE, Nancy A., Religious Studies Dept., Fairfield University, Fairfield CT 06430. (203) 254-4000, X2364; Email: [email protected] Ph.D. 1993 University of Notre Dame. Diss.: Saving History and the Salvation of History in the Trinitarian Theology of Karl Rahner. Trinity, Feminist Theology. GOWANS, Coleen Hoffman, St. Peter's College, 2641 Kennedy Blvd, Jersey City NJ 07306. (201) 915-9231, Ph.D. -

RELIGIEUS BEGRAVEN Levensbeschouwingen Geven

RELIGIEUS BEGRAVEN Levensbeschouwingen geven antwoord op de drie belangrijkste levensvragen: verleden: de vraag naar de oorsprong heden: de vraag naar zingeving toekomst: de vraag naar ‘na de dood’ In het antwoord op de vraag wat er na de dood gebeurt, zijn drie antwoorden te onderscheiden: hiermaals: het leven is eindig, de dood is het einde hiernamaals: het leven is eindig, de dood is een grens hiernanogmaals: het leven is niet eindig, de dood is een overgang naar een nieuw leven Het levensbeschouwelijke landschap is zeer divers. Hoe is op begraafplaatsen die levensbeschouwelijke, c.q. religieuze verscheidenheid terug te vinden? RELIGIE 11 - LABADISTEN Labadisten. Ze bestaan niet meer, ze zijn niet meer dan een klein vlekje in de geschiedenis van religieuze bewegingen, die zich voelden geïnspireerd door de Heilige Geest. De Labadisten vormden in de 17e eeuw een Nederlandse piëtistische godsdienstige sekte onder leiding van Jean de Labadie. Wat er nog aan hen herinnert zijn enkele regels uit het bekende kinderliedje Er kwam ene boer uit Zwitserland (…) labadie, labada, labadonia, de Labadistendyk in Wieuwerd en de mummies in de graf- kelder van de Hervormde kerk van Wieuwerd. Jean de Labadie (1610-1674) De Labadisten ontlenen hun naam aan Jean de Labadie uit Bourg-de-Gironde (bij Bordeaux), die achter- eenvolgens jezuïet, seculier priester, afvallig katholiek, jansenist, en calvinist werd. In 1659 werd hij predikant in Genève. Hier bouwde hij een reputatie op als iemand die een diepgaande vernieuwing van de kerk wilde. Zijn roem ging tot over de grenzen, tot in Nederland toe. Via haar broer Johan Gottschalck van Schurman, hoorde de beroemde Anna Maria van Schurman over hem en o.a.