Arxiv:1902.03828V1 [Cond-Mat.Mtrl-Sci] 11 Feb 2019 Experimental Demonstrations That the Ground State Is a 7–9 ‘Post-Perovskite’ Phase

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Al, Si Retained

Abstracts of Workshop on Transport Properties of the Lower Mantle, Yunishigawa-onsen, Tochigi-ken, Japan, 2008 Scale limits on free-silica seismic scatterers in the lower mantle Craig R. Bina Dept. of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Northwestern University, U.S.A. Seismic velocity anomalies and scatterers of seismic energy in the lower mantle often are attributed to subducted oceanic lithosphere. In particular, silica-saturated basalts in oceanic crust (MORB) under lower mantle conditions should contain high-pressure phases of free silica among assemblages otherwise dominated by silicate perovskite. Free silica phases such as stishovite are expected to generate seismic velocity anomalies that are fast by a few percent relative to surrounding ultramafic peridotite or harzburgite assemblages (Mattern et al. 2002, Bina 2003a, Ricard et al. 2005), and post-stishovite phases such as CaCl2-structured silica may also generate locally slow shear-wave velocity anomalies due to displacive shear-mode transitions (Bina 2003b, Lakshtanov 2007, Konishi et al. 2008). Such models, however, must address the thermodynamic instability of free silica phases in the presence of peridotites or harzburgites, as the silica will react with adjacent ferropericlase (magnesiowüstite) to form silicate perovskite. Thus, any free silica phases preserved in the lower mantle may persist as armored relics, in which silica phases are insulated from surrounding ferropericlase phases by coronas of silicate perovskite. This parallels the situation in crustal metamorphic rocks where, for example, staurolite crystals are often found as armored relics within garnet phases or spinel crystals can be found as relics armored by staurolite poikiloblasts (Whitney 1991, Gil Ibarguchi et al. -

Electrical Conductivity of Minerals and Rocks

1 Electrical conductivity of minerals and rocks Shun-ichiro Karato1 and Duojun Wang1,2 1: Yale University Department of Geology and Geophysics New Haven, CT, USA 2: Key Laboratory of Computational Geodynamics, Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences College of Earth Sciences Beijing 100049, China to be published in “Physics and Chemistry of the Deep Earth” (edited by S. Karato) Wiley-Blackwell 2 SUMMARY Electrical conductivity of most minerals is sensitive to hydrogen (water) content, temperature, major element chemistry and oxygen fugacity. The influence of these parameters on electrical conductivity of major minerals has been characterized for most of the lower crust, upper mantle and transition zone minerals. When the results of properly executed experimental studies are selected, the main features of electrical conductivity in minerals can be interpreted by the physical models of impurity-assisted conduction involving ferric iron and hydrogen-related defects. Systematic trends in hydrogen-related conductivity are found among different types of hydrogen-bearing minerals that are likely caused by the difference in the mobility of hydrogen. A comparison of experimental results with geophysically inferred conductivity shows: (1) Electrical conductivity of the continental lower crust can be explained by a combination of high temperature, high (ferric) iron content presumably associated with dehydration. (2) Electrical conductivity of the asthenosphere can be explained by a modest amount of water (~10-2 wt% in most regions, less than 10-3 wt% in the central/western Pacific). (3) Electrical conductivity of the transition zone requires a higher water content (~10-1 wt% in most regions, ~10-3 wt% in the southern European transition zone, ~1 wt% in the East Asian transition zone). -

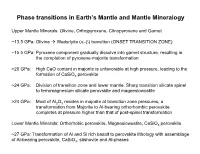

Phase Transitions in Earth's Mantle and Mantle Mineralogy

Phase transitions in Earth’s Mantle and Mantle Mineralogy Upper Mantle Minerals: Olivine, Orthopyroxene, Clinopyroxene and Garnet ~13.5 GPa: Olivine Æ Wadsrlyite (DE) transition (ONSET TRANSITION ZONE) ~15.5 GPa: Pyroxene component gradually dissolve into garnet structure, resulting in the completion of pyroxene-majorite transformation >20 GPa: High CaO content in majorite is unfavorable at high pressure, leading to the formation of CaSiO3 perovskite ~24 GPa: Division of transition zone and lower mantle. Sharp transition silicate spinel to ferromagnesium silicate perovskite and magnesiowustite >24 GPa: Most of Al2O3 resides in majorite at transition zone pressures, a transformation from Majorite to Al-bearing orthorhombic perovskite completes at pressure higher than that of post-spinel transformation Lower Mantle Minerals: Orthorhobic perovskite, Magnesiowustite, CaSiO3 perovskite ~27 GPa: Transformation of Al and Si rich basalt to perovskite lithology with assemblage of Al-bearing perovskite, CaSiO3, stishovite and Al-phases Upper Mantle: olivine, garnet and pyroxene Transition zone: olivine (a-phase) transforms to wadsleyite (b-phase) then to spinel structure (g-phase) and finally to perovskite + magnesio-wüstite. Transformations occur at P and T conditions similar to 410, 520 and 660 km seismic discontinuities Xenoliths: (mantle fragments brought to surface in lavas) 60% Olivine + 40 % Pyroxene + some garnet Images removed due to copyright considerations. Garnet: A3B2(SiO4)3 Majorite FeSiO4, (Mg,Fe)2 SiO4 Germanates (Co-, Ni- and Fe- -

Revision 2 Invited Centennial Review

Revision 2 Invited Centennial Review High-Pressure Minerals Oliver Tschauner ORCID: 0000-0003-3364-8906 University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Geoscience, 4505 Maryland Parkway, Las Vegas, Nevada 89154-4010, U.S.A. This article is dedicated to occurrence, relevance, and structure of minerals whose formation involves high pressure. This includes minerals that occur in the interior of the Earth as well as minerals that are found in shock-metamorphized meteorites and terrestrial impactites. I discuss the chemical and physical reasons which render the definition of high-pressure minerals meaningful, in distinction from minerals that occur under surface-near conditions on Earth or at high temperatures in space or on Earth. Pressure-induced structural transformations in rock- forming minerals define the basic divisions of Earth’s mantle in the upper mantle, transition zone, and lower mantle. Moreover, solubility of minor chemical components in these minerals and the occurrence of accessory phases are influential in mixing and segregating chemical elements in Earth as an evolving planet. Brief descriptions of the currently known high-pressure minerals are presented. Over the past ten years more high-pressure minerals have been discovered than during the previous fifty years, based on the list of minerals accepted by the IMA. The previously unexpected richness in distinct high-pressure mineral species allows for assessment of differentiation processes in the deep Earth. Introduction 1.General aspects of compression of matter over large pressure ranges The pressure in Earth ranges from atmospheric to 136 GPa at the core-mantle boundary, and further, to 360 GPa in the center of the Earth (Dziewonski and Anderson 1981). -

First-Principles Anharmonic Vibrational Study of the Structure of Calcium Silicate Perovskite Under Lower Mantle Conditions

PHYSICAL REVIEW B 99, 064101 (2019) First-principles anharmonic vibrational study of the structure of calcium silicate perovskite under lower mantle conditions Joseph C. A. Prentice,1,2 Ryo Maezono,3 and R. J. Needs2 1Departments of Materials and Physics, and The Thomas Young Centre for Theory and Simulation of Materials, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, United Kingdom 2TCM Group, Cavendish Laboratory, University of Cambridge, J. J. Thomson Avenue, Cambridge CB3 0HE, United Kingdom 3School of Information Science, JAIST, 1-1 Asahidai, Nomi, Ishikawa 923-1292, Japan (Received 29 November 2018; published 6 February 2019) Calcium silicate perovskite (CaSiO3) is one of the major mineral components of the lower mantle, but has been the subject of relatively little work compared to the more abundant Mg-based materials. One of the major problems related to CaSiO3 that is still the subject of research is its crystal structure under lower mantle conditions—a cubic Pm3¯m structure is accepted in general, but some have suggested that lower-symmetry structures may be relevant. In this paper, we use a fully first-principles vibrational self-consistent field method to perform high accuracy anharmonic vibrational calculations on several candidate structures at a variety of points along the geotherm near the base of the lower mantle to investigate the stability of the cubic structure and related distorted structures. Our results show that the cubic structure is the most stable throughout the lower mantle, and that this result is robust against the effects of thermal expansion. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevB.99.064101 I. INTRODUCTION has been relatively neglected, although it is thought to have an effect on the shear velocities of seismic waves as they Of the various layers that make up the internal structure of travel through the Earth, potentially having significance for the Earth, the lower mantle is by far the largest by volume, understanding earthquakes [4,11–13]. -

Crystal Structures of Minerals in the Lower Mantle

6 Crystal Structures of Minerals in the Lower Mantle June K. Wicks and Thomas S. Duffy ABSTRACT The crystal structures of lower mantle minerals are vital components for interpreting geophysical observations of Earth’s deep interior and in understanding the history and composition of this complex and remote region. The expected minerals in the lower mantle have been inferred from high pressure‐temperature experiments on mantle‐relevant compositions augmented by theoretical studies and observations of inclusions in natural diamonds of deep origin. While bridgmanite, ferropericlase, and CaSiO3 perovskite are expected to make up the bulk of the mineralogy in most of the lower mantle, other phases such as SiO2 polymorphs or hydrous silicates and oxides may play an important subsidiary role or may be regionally important. Here we describe the crystal structure of the key minerals expected to be found in the deep mantle and discuss some examples of the relationship between structure and chemical and physical properties of these phases. 6.1. IntrODUCTION properties of lower mantle minerals [Duffy, 2005; Mao and Mao, 2007; Shen and Wang, 2014; Ito, 2015]. Earth’s lower mantle, which spans from 660 km depth The crystal structure is the most fundamental property to the core‐mantle boundary (CMB), encompasses nearly of a mineral and is intimately related to its major physical three quarters of the mass of the bulk silicate Earth (crust and chemical characteristics, including compressibility, and mantle). Our understanding of the mineralogy and density, -

Melting of Iron-Magnesium- Silicate Perovskite

Melting of Iron-Magnesium- Silicate Perovskite Sweeney and Hei nz (1993), GRL 20, 855-858 1 1 Introduction 1. Purpose of study 2. Experimental method 3. Results of the experiments 4. Implications for the lower mantle and CMB 5. Conclusions 2 2 Why study the melting behavior of Fe-Mg-silicate perovskite? • Fe-Mg-silicate perovskite is believed to be the primary mineral phase in the lower mantle and the CMB. • The melting curve of this phase places an upper bound on the temperature of the lower mantle. • Previous studies identified lower and upper bounds of the melting curve; this study identified actual melting temperatures. 3 1. From 670 km down to CMB 2. Implications for style of solid-state convection in the lower mantle 3. Implications for chemical evolution of the mantle 3 Experiments Fe.14Mg.86SiO3 was melted in a laser-heated diamond anvil cell. 1. Enstatite + ruby (80% and 20%) loaded in 100µm sample chambers; without a pressure medium to prevent unwanted reactions. 2. After P calibration, the samples were converted to high P phases. 3. Heated to 1500 K by scanning with stabilized laser. 4. Linearly increase in temperature from 1500K, over four seconds. 5. Thermal analysis to determine the melting temperature. 6. P determined in center and at 3 µm from center to determine “Pby measuring spring-length of the diamond anvil cell. 4 1. 2. relaxation of samples and volume changes due to phase transitions decreased peak pressures by <10 percent. This decrease was compensated by thermal pressure at laser-heated spots. Results will show that the melting behavior is virtually independent of P 3. -

A Model for the Layered Upper Mantle

PHYSICS OFTHE EARTH : , "| AND PLAN ETARY INTERIORS ELSEVIER Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 100 (1997) 197 -212 A model for the layered upper mantle Tibor Gasparik Center for Nigh Pressure Research, Department of Earth and Space Sciences, State Universi~ of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY 1 1794, USA Received 15 August 1995; accepted 21 May 1996 Abstract Numerical modeling of mantle convection by Liu (1994, Science, 264: 1904-1907) favors a two-layer convection, if the results are reinterpreted for the correct phase relations in (Mg,Fe)zSiO 4. The resulting chemical isolation of the upper and lower mantle suggests a highly differentiated and layered upper mantle to account for the discrepancy between the observed compositions of mantle xenoliths and the cosmic abundances of elements. It is shown that a layered upper mantle with a hidden reservoir can have a structure consistent with the observed seismic velocity profiles and an average bulk composition corresponding to the cosmic abundances. The evolution of the upper mantle and the origin of komatiites are discussed in the context of the proposed model. © 1997 Elsevier Science B.V. I. Introduction join (Gasparik, 1989). Until then, the transformation from (Mg,Fe)2SiO 4 olivine to beta phase was the Major progress in our understanding of the Earth's only explanation based on a phase transition. How- interior has been made in the last decade, primarily ever, the concept of a refractory shell residing in the owing to advances in seismology, experimental upper mantle (Gasparik, 1990a) was crucial in find- petrology, geochemistry and mineral physics. -

Partitioning of Iron Between Magnesian Silicate Perovskite and Magnesiowüstite at About 1 Mbar S.E

Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 131 (2002) 295–310 Partitioning of iron between magnesian silicate perovskite and magnesiowüstite at about 1 Mbar S.E. Kesson∗, J.D. Fitz Gerald, H.St.C. O’Neill, J.M.G. Shelley Research School of Earth Sciences, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia Received 3 December 2001; accepted 3 June 2002 Abstract The disproportionation products of olivine Fo90 in diamond–anvil cell experiments at about 1 Mbar are magnesian silicate perovskite Mg# ∼94 and a series of magnesiowüstites Mg# 85–90, yielding a recommended value of 0.4 ± 0.1 for the 2+ distribution coefficient that defines the exchange of Mg and Fe between the two phases (KD). The distinctive compositional trends which would signify that ferric iron had been stabilised during experiments are lacking. Pressure does not exert any significant effect on distribution behaviour, despite thermodynamic predictions of major reallocation of Fe2+ from magnesiowüstite into and in favour of perovskite, towards the base of the lower mantle. Nor does the presence of Al3+ in magnesian silicate perovskite in amounts appropriate for the lower mantle substantially modify distribution behaviour, and hence phase chemistry, provided the oxygen content of the system remains essentially constant. Wood’s [Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 174 (2000) 341] multi-anvil study has been used to link KD with temperature and to calculate that magnesian silicate perovskite Mg# 93.0±0.6 would coexist with magnesiowüstite Mg# 82.6±0.9 just beyond the 660 km discontinuity (1800 K), whilst at the core–mantle boundary (2650 K) the corresponding values would be 91.9 ± 0.4 and 84.9 ± 0.8. -

An Introduction to Post-Perovskite: the Last Mantle Phase Transition

GM01018_CH02.qxd 20/10/07 1:45 PM Page 1 An Introduction to Post-Perovskite: The Last Mantle Phase Transition Kei Hirose1, John Brodholt2, Thorne Lay3, and David A. Yuen4 Discovery of the perovskite to post-perovskite phase transition in MgSiO3, expected to occur for deep mantle conditions, was first announced in April 2004. This immediately stimulated numerous studies in experimental and theoretical mineral physics, seismology, and geodynamics evaluating the implications of a major lower mantle phase change. A resulting revolution in our understanding of the D″ region in the lowermost mantle is well underway. This monograph presents the multidisciplinary advances to date ensuing from interpreting deep mantle seis- mological structures and dynamical processes in the context of the experimentally and theoretically determined properties of the post-perovskite phase change; the last silicate phase change likely to occur with increasing pressure in lowermost mantle rocks. INTRODUCTION boundary. Demonstration of the presence of a well-charac- terized lower mantle phase change raises the prospect of rev- The importance of mineralogical phase transitions in the olutionary improvements in our understanding of lower deep Earth was anticipated in the 1950s by Francis Birch, mantle properties and dynamics. and over the past half century interpretation of seismologi- Following the discovery of silicate perovskite by Liu cal structures by mineralogical phase equilibria has guided [1974], MgSiO3 perovskite has become recognized as the compositional, thermal and dynamical models of the planet’s principal mineral occurring in Earth’s lower mantle. For sev- interior. Confident seismological detection of the occur- eral decades, MgSiO3 perovskite has been extensively stud- rence of a specific predicted phase change at depth enables ied to clarify its physical properties, crystal chemistry, and a cascade of constraints to be placed on deep properties that role in mantle dynamics. -

Subject Index, Volume 84, 1999

American Mineralogist, Volume 84, pages 1985–1992, 1999 SUBJECT INDEX, VOLUME 84, 1999 Aenigmatite 257 andalusite 1727 ites and related rocks. By A.F. Aerinite 1467 Annealing 1213, 1224, 1235 Glazner 1210 AFM (SFM, STM) 620, 884 Anion-centered tetrahedra 1099 Coppens, P.: X-Ray Charge hematite 1061 Anomalous scattering 294 Densities and Chemical Bonding. ilmenite 1384 Arnhemite 193 By J.W.Downs 690 pyrite 1549 Apatite 581, 977, 1213, 1224, 1235, Dyar, M.D., McCammon, C. Akimotite 226, 233, 267 1346 and Schaefer M.W.: Mineral Al2SiO5 group 1152 dental 1406 Spectroscopy: A Tribute to Roger Albite 27, 333, 726, 746, 1144 Armenite 86, 92 G. Burns. By A. Treiman 211 melting 1830 Arsenides 639 Grew, E.S. and Anovitz, L.M.: ALH84001 1569 Ashanite 688 Boron: Mineralogy, Petrology Alkali basalt 357 Au, As in pyrite 1071 and Geochemistry. By E.E Allanite 1346 Auorthosites 806 Foord, J.T. O’Connor 1209 Almandine 374 Au2SbO2(OH) 197 Hughes, R.W.: Ruby and Sapphire. AlO6 octahedral chains 1152 Averievite 685 By J. Sinkankas 211 Aluminosilicates 152, 311, 345, 465, Awards Moore, D.M. and Reynolds, R. C., Jr.: 983 Distinguished Public Service X-ray Diffraction and the Identifi- Alunite-group minerals 1687 Medal, acceptance of 1207 cation and Analysis of Clay Miner- Amphibole 1, 86, 102, 1033, 1304 Distinguished Public Service als, second edition. By S.P. Altaner, Analcime 112 Medal, presentation of 1205 689 Analysis chem. (mineral) 1170 Mineralogical Society of America, Young, D.A.: N.L. Bowen and aenigmatite 257 acceptance of 1203 cystallization—differentation: amphibole 102 Mineralogical Society of America, The evolution of a theory.By bederite 1674 presentation of 1202 H.S. -

Chemistry of the Lower Mantle

18 Chemistry of the Lower Mantle Daniel J. Frost and Robert Myhill ABSTRACT Various lines of evidence have been used to argue that the lower mantle is chemically distinct in major elements from the upper mantle. One of the few approaches that may clarify this would be to compare observed seismic velocities with estimates computed from mineral physical models. This requires a method for determining the chemistry and modes of mantle minerals for a given bulk composition as a function of pressure and tempera- ture. Aside from phase changes near the core‐mantle boundary, the main change taking place throughout the bulk of an isochemical mantle will be the exchange of Fe between the principal minerals ferropericlase and bridgmanite. Here we review experimental data for this exchange and present simple models to describe this behavior. All experimental data to date seem to indicate that bridgmanite will contain subequal proportions of both Fe2+ and Fe3+ throughout much of the lower mantle. If the entire mantle is isochemical, the low Fe3+ contents of the upper mantle imply that metallic Fe should exist in the lower mantle. An alternative hypothesis is that the lower mantle is oxygen enriched but becomes reduced by the oxidation of species such as carbon during upwelling. 18.1. IntrODUCTION constraints on the processes involved in the accretion and differentiation of Earth would be lost if element concen- Earth’s lower mantle, extending from 660 to 2891 km trations in the upper mantle could not be reliably assumed depth, contains ~70% of the mass of the mantle and is to reflect the mantle as a whole.