ICL Technical Journal Volume 6 Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Validated Products List, 1995 No. 3: Programming Languages, Database

NISTIR 5693 (Supersedes NISTIR 5629) VALIDATED PRODUCTS LIST Volume 1 1995 No. 3 Programming Languages Database Language SQL Graphics POSIX Computer Security Judy B. Kailey Product Data - IGES Editor U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Technology Administration National Institute of Standards and Technology Computer Systems Laboratory Software Standards Validation Group Gaithersburg, MD 20899 July 1995 QC 100 NIST .056 NO. 5693 1995 NISTIR 5693 (Supersedes NISTIR 5629) VALIDATED PRODUCTS LIST Volume 1 1995 No. 3 Programming Languages Database Language SQL Graphics POSIX Computer Security Judy B. Kailey Product Data - IGES Editor U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Technology Administration National Institute of Standards and Technology Computer Systems Laboratory Software Standards Validation Group Gaithersburg, MD 20899 July 1995 (Supersedes April 1995 issue) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Ronald H. Brown, Secretary TECHNOLOGY ADMINISTRATION Mary L. Good, Under Secretary for Technology NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF STANDARDS AND TECHNOLOGY Arati Prabhakar, Director FOREWORD The Validated Products List (VPL) identifies information technology products that have been tested for conformance to Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) in accordance with Computer Systems Laboratory (CSL) conformance testing procedures, and have a current validation certificate or registered test report. The VPL also contains information about the organizations, test methods and procedures that support the validation programs for the FIPS identified in this document. The VPL includes computer language processors for programming languages COBOL, Fortran, Ada, Pascal, C, M[UMPS], and database language SQL; computer graphic implementations for GKS, COM, PHIGS, and Raster Graphics; operating system implementations for POSIX; Open Systems Interconnection implementations; and computer security implementations for DES, MAC and Key Management. -

IDMS Conversion

IDMS Conversion The Modern Systems IDMS conversion includes the generation of a new relational database to replace the functionality, set relationships, indexes, and data structures that are currently part of the IDMS network database. The new target database can reside on or off the mainframe, and can use any of the standard relational database management systems (RDBMS): Microsoft SQL Server, Oracle or IBM DB2. Database Functionality DB-Shuttle™ provides The Modern Systems solution provides a complete replacement for all IDMS automated technology database functionality: that protects legacy assets, reduces • IDMS record layouts maintenance costs, • Group-level elements, Occurs and Redefines clauses within IDMS record provides agility and definitions flexibility, and enables • Set definitions (record-to-record relationships) Service-Oriented • System-owned indexes Architecture (SOA) • Bill-of-material structures within business-critical • Multi-member sets, multi-set relationships between two record types applications. • Duplicate CALC designations • Sorted sets, Chained sets and NEXT sets Relational Results The resulting database is fully relational. Primary keys, foreign keys and index definitions are automatically created. All constraints are generated into the resulting DDL. Table spaces, indexes, table names and column names are all generated according to your naming standards. Delivered Components As part of the delivery process, Modern Systems generates and delivers the following component types for installation in the new relational -

Technical Details of the Elliott 152 and 153

Appendix 1 Technical Details of the Elliott 152 and 153 Introduction The Elliott 152 computer was part of the Admiralty’s MRS5 (medium range system 5) naval gunnery project, described in Chap. 2. The Elliott 153 computer, also known as the D/F (direction-finding) computer, was built for GCHQ and the Admiralty as described in Chap. 3. The information in this appendix is intended to supplement the overall descriptions of the machines as given in Chaps. 2 and 3. A1.1 The Elliott 152 Work on the MRS5 contract at Borehamwood began in October 1946 and was essen- tially finished in 1950. Novel target-tracking radar was at the heart of the project, the radar being synchronized to the computer’s clock. In his enthusiasm for perfecting the radar technology, John Coales seems to have spent little time on what we would now call an overall systems design. When Harry Carpenter joined the staff of the Computing Division at Borehamwood on 1 January 1949, he recalls that nobody had yet defined the way in which the control program, running on the 152 computer, would interface with guns and radar. Furthermore, nobody yet appeared to be working on the computational algorithms necessary for three-dimensional trajectory predic- tion. As for the guns that the MRS5 system was intended to control, not even the basic ballistics parameters seemed to be known with any accuracy at Borehamwood [1, 2]. A1.1.1 Communication and Data-Rate The physical separation, between radar in the Borehamwood car park and digital computer in the laboratory, necessitated an interconnecting cable of about 150 m in length. -

Miami-Dade County

MIAMI-DADE COUNTY Cognos Business Analytics and IDMS Integration at Miami-Dade County Abstract of the Program Miami-Dade County led the way as the first company in the world to successfully extract information from a CA IDMS network database using IBM Cognos Business Analytics. Miami- Dade County stores the majority of their critical data, such as Criminal Justice, Payroll, Traffic and Building information in CA IDMS mainframe databases and traditionally extracts this data using Computer Associates CA IDMS tools (CA ADS ADS/O and IDMS/Cobol/IDMS). Through the collaboration of CA Computer Associates, IBM, and Miami-Dade County, a driver was created for IBM Cognos to access this data directly by using Business Analytics tools without the need for exporting the data into a contemporary distributed environment. The problem or need for the program IDMS (Integrated Database Management System) is primarily a network (CODASYL) database management system for mainframes. Only CA tools could access IDMS data. IDMS mainframe technology did not have the capability to be accessed directly by contemporary business analytics software solutions. This limitation required data extraction, file transfer protocols, and script loading processes to expose IDMS, IMS, and DB2 mainframe data to contemporary technologies, including business analytics tools like IBM Cognos Analytics. Multiple data warehouses and operational data stores are loaded from the primary data sources originating from the IDMS mainframe platform and other relational data sources. More than 50 production IDMS databases are actively supported and used county-wide at Miami- Dade County. Access to data by the distributed world such as making the data available on an Oracle or MSSQL database requires adding multiple intermediate steps, using multiple technologies, and multiple points of failure to migrate data and make it available to analytic technologies. -

David Hartley a Promise of Funding Has Been Received and an Outline Plan Including Cost Estimates and Timescales Has Been Drawn Up

Issue Number 54 Spring 2011 Computer Conservation Society Aims and objectives The Computer Conservation Society (CCS) is a co-operative venture between the British Computer Society (BCS), the Science Museum of London and the Museum of Science and Industry (MOSI) in Manchester. The CCS was constituted in September 1989 as a Specialist Group of the British Computer Society. It is thus covered by the Royal Charter and charitable status of the BCS. The aims of the CCS are: To promote the conservation of historic computers and to identify existing computers which may need to be archived in the future, To develop awareness of the importance of historic computers, To develop expertise in the conservation and restoration of historic computers, To represent the interests of Computer Conservation Society members with other bodies, To promote the study of historic computers, their use and the history of the computer industry, To publish information of relevance to these objectives for the information of Computer Conservation Society members and the wider public. Membership is open to anyone interested in computer conservation and the history of computing. The CCS is funded and supported by voluntary subscriptions from members, a grant from the BCS, fees from corporate membership, donations, and by the free use of the facilities of both museums. Some charges may be made for publications and attendance at seminars and conferences. There are a number of active Projects on specific computer restorations and early computer technologies and software. -

Computer Conservation Society

Issue Number 88 Winter 2019/20 Computer Conservation Society Aims and Objectives The Computer Conservation Society (CCS) is a co-operative venture between BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT; the Science Museum of London; and the Science and Industry Museum (SIM) in Manchester. The CCS was constituted in September 1989 as a Specialist Group of the British Computer Society. It is thus covered by the Royal Charter and charitable status of BCS. The objects of the Computer Conservation Society (“Society”) are: To promote the conservation, restoration and reconstruction of historic computing systems and to identify existing computing systems which may need to be archived in the future; To develop awareness of the importance of historic computing systems; To develop expertise in the conservation, restoration and reconstruction of historic computing systems; To represent the interests of the Society with other bodies; To promote the study of historic computing systems, their use and the history of the computer industry; To publish information of relevance to these objectives for the information of Society members and the wider public. Membership is open to anyone interested in computer conservation and the history of computing. The CCS is funded and supported by a grant from BCS and from donations. There are a number of active projects on specific computer restorations and early computer technologies and software. Younger people are especially encouraged to take part in order to achieve skills transfer. The CCS also enjoys a close relationship with the National Museum of Computing. Resurrection The Journal of the Computer Conservation Society ISSN 0958-7403 Number 88 Winter 2019/20 Contents Society Activity 2 News Round-Up 9 The Data Curator 10 Paul Cockshott From Tea Shops to Computer Company: The Improbable 15 Story of LEO John Aeberhard Book Review: Early Computing in Britain Ferranti Ltd. -

Latest Results from the Procedure Calling Test, Ackermann's Function

Latest results from the procedure calling test, Ackermann’s function B A WICHMANN National Physical Laboratory, Teddington, Middlesex Division of Information Technology and Computing March 1982 Abstract Ackermann’s function has been used to measure the procedure calling over- head in languages which support recursion. Two papers have been written on this which are reproduced1 in this report. Results from further measurements are in- cluded in this report together with comments on the data obtained and codings of the test in Ada and Basic. 1 INTRODUCTION In spite of the two publications on the use of Ackermann’s Function [1, 2] as a mea- sure of the procedure-calling efficiency of programming languages, there is still some interest in the topic. It is an easy test to perform and the large number of results ob- tained means that an implementation can be compared with many other systems. The purpose of this report is to provide a listing of all the results obtained to date and to show their relationship. Few modern languages do not provide recursion and hence the test is appropriate for measuring the overheads of procedure calls in most cases. Ackermann’s function is a small recursive function listed on page 2 of [1] in Al- gol 60. Although of no particular interest in itself, the function does perform other operations common to much systems programming (testing for zero, incrementing and decrementing integers). The function has two parameters M and N, the test being for (3, N) with N in the range 1 to 6. Like all tests, the interpretation of the results is not without difficulty. -

Sperry Rand's Third-Generation Computers 1964–1980

Sperry Rand’s Third-Generation Computers 1964–1980 George T. Gray and Ronald Q. Smith The change from transistors to integrated circuits in the mid-1960s marked the beginning of third-generation computers. A late entrant (1962) in the general-purpose, transistor computer market, Sperry Rand Corporation moved quickly to produce computers using ICs. The Univac 1108’s success (1965) reversed the company’s declining fortunes in the large-scale arena, while the 9000 series upheld its market share in smaller computers. Sperry Rand failed to develop a successful minicomputer and, faced with IBM’s dominant market position by the end of the 1970s, struggled to maintain its position in the computer industry. A latecomer to the general-purpose, transistor would be suitable for all types of processing. computer market, Sperry Rand first shipped its With its top management having accepted the large-scale Univac 1107 and Univac III comput- recommendation, IBM began work on the ers to customers in the second half of 1962, System/360, so named because of the intention more than two years later than such key com- to cover the full range of computing tasks. petitors as IBM and Control Data. While this The IBM 360 did not rely exclusively on lateness enabled Sperry Rand to produce rela- integrated circuitry but instead employed a tively sophisticated products in the 1107 and combination of separate transistors and chips, III, it also meant that they did not attain signif- called Solid Logic Technology (SLT). IBM made icant market shares. Fortunately, Sperry’s mili- a big event of the System/360 announcement tary computers and the smaller Univac 1004, on 7 April 1964, holding press conferences in 1005, and 1050 computers developed early in 62 US cities and 14 foreign countries. -

FEBRUARY 1981 R

THE ISSN 004-8917 AUSTRALIAN COMPUTER JOURNAL VOLUME 13, NUMBER 1, FEBRUARY 1981 r CONTENTS INVITED PAPER 1-6 Software and Hardware Technology for the ICL Distributed Array Processor R.W. GOSTICK ADVANCED TUTORIALS 7-12 On Understanding Binary Search B.P. KIDMAN 13-23 Some Trends in System Design Methodologies I.T. HAWRYSZKIEWYCZ SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 24-25 NEBALL and FINGRP: New Programs for Multiple Nearest- Neighbour Analysis D.J. ABEL and W.T. WILLIAMS 26 Program INVER Revisited D.J. ABEL and W.T. WILLIAMS 27-28 A Comparison between PASCAL, FORTRAN and PL/1 D.J. KEWLEY SPECIAL FEATURES 29 Book Reviews 30-31 Letters to the Editor 32 Call for Papers V J Published for Australian Computer Society Incorporated Registered for Posting as a Publication — Category B “This wouldn't have happened, Fenwick, with a Tandem NonStop™ System," When your computers down, are you out or business? You can bank on it. Timing couldn’t be worse. No question about it. Your busiest season. Customers pounding for service. When you’re on a Tandem NonStop™ System, your information All it takes is one small failure somewhere in the system. One files and your processes are protected from contamination in a disc or disc controller. One input/output channel. way no other system can match. We’ve built in safeguards other For want of an alternative, the system is down and business is suppliers can only dream about. You’ve heard the war stories about lost. Sometimes forever. restart and restore data base on other systems. They’re not exaggerations, but they can be a thing of the past. -

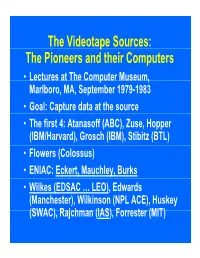

P the Pioneers and Their Computers

The Videotape Sources: The Pioneers and their Computers • Lectures at The Compp,uter Museum, Marlboro, MA, September 1979-1983 • Goal: Capture data at the source • The first 4: Atanasoff (ABC), Zuse, Hopper (IBM/Harvard), Grosch (IBM), Stibitz (BTL) • Flowers (Colossus) • ENIAC: Eckert, Mauchley, Burks • Wilkes (EDSAC … LEO), Edwards (Manchester), Wilkinson (NPL ACE), Huskey (SWAC), Rajchman (IAS), Forrester (MIT) What did it feel like then? • What were th e comput ers? • Why did their inventors build them? • What materials (technology) did they build from? • What were their speed and memory size specs? • How did they work? • How were they used or programmed? • What were they used for? • What did each contribute to future computing? • What were the by-products? and alumni/ae? The “classic” five boxes of a stored ppgrogram dig ital comp uter Memory M Central Input Output Control I O CC Central Arithmetic CA How was programming done before programming languages and O/Ss? • ENIAC was programmed by routing control pulse cables f ormi ng th e “ program count er” • Clippinger and von Neumann made “function codes” for the tables of ENIAC • Kilburn at Manchester ran the first 17 word program • Wilkes, Wheeler, and Gill wrote the first book on programmiidbBbbIiSiing, reprinted by Babbage Institute Series • Parallel versus Serial • Pre-programming languages and operating systems • Big idea: compatibility for program investment – EDSAC was transferred to Leo – The IAS Computers built at Universities Time Line of First Computers Year 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 ••••• BTL ---------o o o o Zuse ----------------o Atanasoff ------------------o IBM ASCC,SSEC ------------o-----------o >CPC ENIAC ?--------------o EDVAC s------------------o UNIVAC I IAS --?s------------o Colossus -------?---?----o Manchester ?--------o ?>Ferranti EDSAC ?-----------o ?>Leo ACE ?--------------o ?>DEUCE Whirl wi nd SEAC & SWAC ENIAC Project Time Line & Descendants IBM 701, Philco S2000, ERA.. -

CASE STUDY GE CAPITAL ASSESSING, CONVERTING, & REPLATFORMING a MASSIVE BUSINESS CRITICAL APPLICATION with ASTONISHING RESULTS Introduction

CASE STUDY GE CAPITAL ASSESSING, CONVERTING, & REPLATFORMING A MASSIVE BUSINESS CRITICAL APPLICATION WITH ASTONISHING RESULTS Introduction GE Capital is the financial services unit of the American conglomerate General Electric, it provides commercial lending and leasing, as well as a range of financial services for consumers. Most of GE Capital’s commercial loans are to small and midsized companies, spread across multiple industries and geographies, and secured by tangible assets. GE Capital’s consumer lending activities are also diversified by product and geography and include operations in 55 countries. Project Summary GE Capital was looking to move their PMS suite of $ 2014 Net Income: $7.0 billion applications from ADS/O and COBOL/IDMS running 2014 Assets: $499 billion on a mainframe, to COBOL running with Oracle on Unix without changing the user interface in the Operations in 40+ Countries process. PMS was built by GE Capital in 1987 500,000+ Commercial Customers and began its life as a 20,000 account schedule system without any interfaces. 35,000+ Employees As with most homegrown systems, it was built out of necessity and to serve the business as it existed at the time. Over the decades, this small system grew in size and complexity to become the central nervous system of both GE Capital’s direct and indirect business units comprised of four highly customized implementations. With over 5 million account schedules, 382 interfaces, 1,700 concurrent users, and 3.5 million transactions per day running against 71 million lines of code, the PMS system had come a long way from its humble roots. -

Legal Picture of the Law of the Sea Would in Any Case Be Confusing

THE BAI TIC STRAITS oastal StateS. In What Nay be its prinCi al h evement, UNCLOShas developed such a re i See also ibid., at . 121 ~ " ' i convention, however, thee UNCLOSUNC straits destined to serve as a powerfulf mod.el deve Lopment o f a new customarus omary law1 of straits ~t tI Some may even que stion. whet her a sin le multi- Caraca.s Convention wo u lda equately cover of physical, navigational a, po 1'itical, and ems e ar anelles, G braltax', Malacca, the Danish Straits Bah 1- e Qt er nar rows. These skepticsep ics mayma askk bi 1 ate.ra l or specia 1 regional agreements . geweniq, ~eu re, note 1, p. 67. COMMENTARY Ib R. Andreasen Ambassador Ministry of Foreign Affairs Denmark I was indeed very honoredwhen the Lawof the Sea Institute asked me to be one of the commentators on the subject of "TheBaltic Straits." Knowingthe usualvery high academicstandards of the Conferences of the Institute, I heSitated in OfferingNy VieW- pointsin sucha distinguishedgathering. Being here andseeing so manywell knownprofessors of interna- tional law, andespecialLy after listeningto the ex- tremelyinteresting and comprehensive speech by Pro- fessorVitzthum, I think I shouldhave hesitated even Nore. Qnthe otherhand, it mightafter all beof interestto the conferenceto have an input on the Straitsissue which originates more from practical experiencethan f romacademic studies. Beforecommenting onthe Straits issue I would, however,like to makesome general remarks in rela- tionto ProfessorVitzthum's introduction. I under- stoodhim to saythat, irrespective ofwhether ornot a newLaw of theSea Convention cameinto force, the legalpicture of thelaw of the sea would inany case beconfusing.