A Historical Perspective of the Development of British Computer Manufacturers with Particular Reference to Staffordshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish Bulletin 31.05.20.Pub

THE CATHOLIC PASTORAL PARTNERSHIP OF BIDDULPH, GOLDENHILL, KIDSGROVE & PACKMOOR UNDER THE PATRONAGE AND PROTECTION OF OUR LADY OF GRACE SUNDAY BULLETIN PENTECOST SUNDAY SUNDAY 31ST MAY 2020 CHURCHES A WORD FROM THE PARISH PRIEST Biddulph English Martyrs’ Church, Church Road, Biddulph, tion of how we will come guidance is at the moment) ST8 6NE out of the lockdown clo- not be over 70 years old, Goldenhill St Joseph’s Church, sure of churches. It is likely nor have underlying health High Street, Stoke-on-Trent, ST6 to take place in July. The conditions. This is because 5RD first stage will be that we, under the law, have a Kidsgrove St John the Evange- churches will be open for duty of care to volunteers list’s Church, The Avenue, personal prayer, before to safeguard their health Kidsgrove, ST7 1AE being opened again for and safety as far as possi- Packmoor St Patrick’s Church, public celebration of Mass. ble. We have the next Mellor Street, Packmoor, Stoke- The Vicar General has indi- month to get everything in on-Trent, ST7 4SN I wish you a blessed Feast cated that only churches place so that we are ready of Pentecost! Some of you that can guarantee the re- to re-open when the word KEY CONTACTS have been following the quired social distancing comes from the hierarchy Parish Priest nine days of the Pentecost will be able to open. As I that we are able. Rev Fr Julian C Green Novena with me online. I said last week, in our part- Assistant Priest Opening the churches hope that it was a blessed nership, when we open, it Rev Fr Prabhakar Pamisetty MF physically is as nothing time for you, and that the will be St Joseph’s and St Joseph’s Presbytery compared to opening up consecration to the Holy English Martyrs’ which 715 High Street the life of the Church Spirit that we make today will be the first to open. -

Technical Details of the Elliott 152 and 153

Appendix 1 Technical Details of the Elliott 152 and 153 Introduction The Elliott 152 computer was part of the Admiralty’s MRS5 (medium range system 5) naval gunnery project, described in Chap. 2. The Elliott 153 computer, also known as the D/F (direction-finding) computer, was built for GCHQ and the Admiralty as described in Chap. 3. The information in this appendix is intended to supplement the overall descriptions of the machines as given in Chaps. 2 and 3. A1.1 The Elliott 152 Work on the MRS5 contract at Borehamwood began in October 1946 and was essen- tially finished in 1950. Novel target-tracking radar was at the heart of the project, the radar being synchronized to the computer’s clock. In his enthusiasm for perfecting the radar technology, John Coales seems to have spent little time on what we would now call an overall systems design. When Harry Carpenter joined the staff of the Computing Division at Borehamwood on 1 January 1949, he recalls that nobody had yet defined the way in which the control program, running on the 152 computer, would interface with guns and radar. Furthermore, nobody yet appeared to be working on the computational algorithms necessary for three-dimensional trajectory predic- tion. As for the guns that the MRS5 system was intended to control, not even the basic ballistics parameters seemed to be known with any accuracy at Borehamwood [1, 2]. A1.1.1 Communication and Data-Rate The physical separation, between radar in the Borehamwood car park and digital computer in the laboratory, necessitated an interconnecting cable of about 150 m in length. -

Staffordshire 30Undar Es W Th Cheshire Derbyshire Wa Rw Ckshiir and Refg Rid an D Worcester Local

No. 5H2 Review of Non-Metropolitan Counties. COUNTY OF STAFFORDSHIRE 30UNDAR ES W TH CHESHIRE DERBYSHIRE WA RW CKSHIIR AND REFG RID AN D WORCESTER LOCAL BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOH ENGLAND RETORT NO •5112 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Mr G J Ellerton CMC MBE DEPUTY CHAIRMAN Mr J G Powell CBE FRICS FSVA Members Mr K F J Ennals CB Mr G R Prentice Mrs H R V Sarkany PATTEN.PPD THE RT. HON. CHRIS PATTEN HP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT REVIEW OF NON-METROPOLITAN COUNTIES COUNTY OF STAFFORDSHIRE: BOUNDARIES WITH CHESHIRE, DERBYSHIRE,. WARWICKSHIRE, AND HEREFORD AND WORCESTER COMMISSION'S FINAL REPORT AND PROPOSALS INTRODUCTION 1. On 26 July 1985 we wrote to Staffordshire County Council announcing our intention to undertake a review of the County under Section 48(1) of the Local Government Act 1972. Copies of our letter were sent to all the principal local authorities and parishes in Staffordshire, and in the adjoining counties of Cheshire, Derbyshire, West Midlands, Shropshire, Warwickshire, Hereford and Worcester and Leicestershire; to the National and County Associations of Local Councils; to the Members of Parliament with constituency interests and to the headquarters of the main political parties. In addition copies were sent to those government departments with an interest; regional health authorities; public utilities in the area; the English Tourist Board; the editors of the Municipal Journal and Local Government Chronicle; and to local television and radio stations serving the area. 2. The County Councils were requested to co-operate as necessary with each other, and with the District Councils concerned, to assist us in publicising the start of the review, by inserting a notice for two successive weeks in local newspapers so as to give a wide coverage in the areas concerned. -

Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan

Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council October 2020 Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Prepared for: Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council AECOM Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan Table of Contents 1. Foreword ......................................................................................................... 5 2. Executive Summary ......................................................................................... 6 3. Contextual analysis ......................................................................................... 9 Kidsgrove Town Deal Investment Area ............................................................................................................. 10 Kidsgrove’s assets and strengths .................................................................................................................... 11 Challenges facing the town ............................................................................................................................. 15 Key opportunities for the town ......................................................................................................................... 19 4. Strategy ......................................................................................................... 24 Vision ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Annual Report FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS

2019 Annual Report FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS Some of the information we provide in this document is forward-looking and therefore INSIDE FRONT COVER could change over time to reflect changes in the environment in which GE competes. For details on the uncertainties that may cause our actual results to be materially different Wysheka Austin, Senior Operations than those expressed in our forward-looking statements, see https://www.ge.com/ Manager, works on a combustion unibody investor-relations/important-forward-looking-statement-information. for GE Gas Power’s 7HA gas turbine in Greenville, South Carolina. We do not undertake to update our forward-looking statements. NON-GAAP FINANCIAL MEASURES COVER We sometimes use information derived from consolidated financial data but not presented Kevin Jones, a Development Assembly in our financial statements prepared in accordance with U.S. generally accepted accounting Mechanic, performs a perfection review on principles (GAAP). Certain of these data are considered “non-GAAP financial measures” the propulsor for GE Aviation’s GE9X engine under the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission rules. These non-GAAP financial before it is shipped for certification testing. measures supplement our GAAP disclosures and should not be considered an alternative to the GAAP measure. The reasons we use these non-GAAP financial measures and the reconciliations to their most directly comparable GAAP financial measures can be found on pages 43-49 of the Management’s Discussion and Analysis within our Form 10-K and in GE’s fourth-quarter 2019 earnings materials posted to ge.com/investor, as applicable. Dear fellow shareholder, Over 60 GE wind turbines work together at Meikle Wind Farm, the largest wind farm in Western Canada, to generate enough energy to power over 54,000 homes in British Columbia. -

Stoke-On-Trent ST8 7DN A

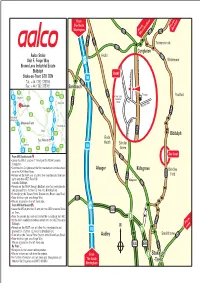

From The North From Warrington Buxton A54 From A54 MacclesfieldA34 A50 Timbersbrook A5022 A534 Congleton Aalco Stoke Arclid A527 J17 T Whitemoor Unit F, Forge Way u n s Brown Lees Industrial Estate t al A34 Biddulph l R Inset y o a Stoke-on-Trent ST8 7DN a W M6 d A533 e Brown Le g Tel: +44 1782 375700 r o Fax: +44 1782 375701 Sandbach F A50 A34 A60 e Texaco Brown Lees s Poolfold M6 Congleton A614 A53 M1 Industrial R Estate oad J17 A6 Mansfield ay A534 ria W Biddulph Victo J28 A533 A38 J16 A52 A527 Newcastle- Under-Lyme J26 ay W J15 Stoke-on-Trent t c Nottingham e p A53 A50 J25 s Derby o r A527 A453 P Biddulph A34 J24 Rode East Midlands A34 Heath Scholar Stafford A46 M6 A38 Green M6 A51 A42 M1 A6 See Inset From M6 Southbound A50 Leave the M6 at junction 17 and join the A534 towards Congleton. A533 Continue into Congleton at the first roundabout continue ahead Alsager Kidsgrove Brindley onto the A34 West Road. Remain on the A34 over a further two roundabouts then turn Ford A527 right onto the A527 Rood Hill. A34 Kidsgrove A50 towards Biddulph. Remain on the A534 through Biddulph over four roundabouts and proceed for a further 1/2 mile into Brindley Ford. Turn right at the Texaco Petrol Station onto Brown Lees Road. Take the first right onto Forge Way. A500 We are situated on the left hand side. From M6 Northbound J16 Leave the M6 at junction 16 and join the A500 towards Stoke A500 on Trent. -

2016 Annual Report Table of Contents

Association of the United States Army 2016 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President & CEO . 3. Education . 4. Professional Development . .4 . Publications . 7. Digital & Social Media . 10. Advocacy & Outreach . .11 . Government Affairs. 11 Family Readiness . .14 . NCO & Soldier Programs . 15. Membership & Chapters. 16 Financials . .18 . Awards . 19 Sustaining Members . 21. 2 LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT & CEO In 2016 we experienced a year full of change—for our nation, for the Army and for the Association of the United States Army (AUSA). During what can only be described as a tumultuous political year, our nation experienced a presidential campaign unlike any other I can recall. National security factored promi- nently in the campaign, particularly in several of the debates. AUSA, true to our non-par- tisan tradition, provided a platform for the advancement of a strong defense based on our uniquely American values. “America’s Purpose,” a short, but impactful, document published by AUSA, offered thoughts of how the next president, irrespective of party, might craft an effective foreign policy. This initiative, led by GEN Gordon Sullivan, U.S. Army Retired, LTG Guy Swan, U.S. Army Retired, LTC Douglas Merritt and Richard Lim, presented GEN Carter F. Ham, U.S. Army “America’s Purpose” to the most senior advisors to both leading presidential candidates. Retired, President & CEO, AUSA You’ll find “America’s Purpose” in the Publications section of our website and I encourage you to read it. For us at the AUSA National Office, the biggest change was the retirement of General Sullivan after more than 18 years as president & chief executive officer. -

Submission to the Local Boundary Commission for England Further Electoral Review of Staffordshire Stage 1 Consultation

Submission to the Local Boundary Commission for England Further Electoral Review of Staffordshire Stage 1 Consultation Proposals for a new pattern of divisions Produced by Peter McKenzie, Richard Cressey and Mark Sproston Contents 1 Introduction ...............................................................................................................1 2 Approach to Developing Proposals.........................................................................1 3 Summary of Proposals .............................................................................................2 4 Cannock Chase District Council Area .....................................................................4 5 East Staffordshire Borough Council area ...............................................................9 6 Lichfield District Council Area ...............................................................................14 7 Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council Area ....................................................18 8 South Staffordshire District Council Area.............................................................25 9 Stafford Borough Council Area..............................................................................31 10 Staffordshire Moorlands District Council Area.....................................................38 11 Tamworth Borough Council Area...........................................................................41 12 Conclusions.............................................................................................................45 -

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War INCLUDING Lightning Canberra Harrier Vulcan www.keypublishing.com RARE IMAGES AND PERIOD CUTAWAYS ISSUE 38 £7.95 AA38_p1.indd 1 29/05/2018 18:15 Your favourite magazine is also available digitally. DOWNLOAD THE APP NOW FOR FREE. FREE APP In app issue £6.99 2 Months £5.99 Annual £29.99 SEARCH: Aviation Archive Read on your iPhone & iPad Android PC & Mac Blackberry kindle fi re Windows 10 SEARCH SEARCH ALSO FLYPAST AEROPLANE FREE APP AVAILABLE FOR FREE APP IN APP ISSUES £3.99 IN APP ISSUES £3.99 DOWNLOAD How it Works. Simply download the Aviation Archive app. Once you have the app, you will be able to download new or back issues for less than newsstand price! Don’t forget to register for your Pocketmags account. This will protect your purchase in the event of a damaged or lost device. It will also allow you to view your purchases on multiple platforms. PC, Mac & iTunes Windows 10 Available on PC, Mac, Blackberry, Windows 10 and kindle fire from Requirements for app: registered iTunes account on Apple iPhone,iPad or iPod Touch. Internet connection required for initial download. Published by Key Publishing Ltd. The entire contents of these titles are © copyright 2018. All rights reserved. App prices subject to change. 321/18 INTRODUCTION 3 RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War cramble! Scramble! The aircraft may change, but the ethos keeping world peace. The threat from the East never entirely dissipated remains the same. -

Auction Results June 2021

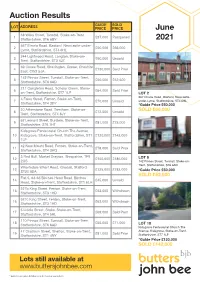

Auction Results GUIDE SOLD LOT ADDRESS PRICE PRICE June 38 Wilks Street, Tunstall, Stoke-on-Trent, 1 £37,000 Postponed Staffordshire, ST6 6BY 2021 567 Etruria Road, Basford, Newcastle-under- 2 £50,000 £66,000 Lyme, Staffordshire, ST4 6HL 244 Lightwood Road, Longton, Stoke-on- 3 £90,000 Unsold Trent, Staffordshire, ST3 4JZ 69 Crewe Road, Shavington, Crewe, Cheshire 4 £130,000 Sold Prior East, CW2 5JA 142 Pinnox Street, Tunstall, Stoke-on-Trent, 5 £50,000 £52,500 Staffordshire, ST6 6AD 211 Congleton Road, Scholar Green, Stoke- 6 £64,000 Sold Prior on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST7 1LP LOT 2 567 Etruria Road, Basford, Newcastle- 4 Foley Street, Fenton, Stoke-on-Trent, 7 £70,000 Unsold under-Lyme, Staffordshire, ST4 6HL Staffordshire, ST4 3DY *Guide Price £50,000 20 Atherstone Road, Trentham, Stoke-on- 8 £72,500 Unsold SOLD £66,000 Trent, Staffordshire, ST4 8JY 62 Leonard Street, Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, 9 £81,000 £75,000 Staffordshire, ST6 1HT Kidsgrove Pentecostal Church The Avenue, 10 Kidsgrove, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST7 £120,000 £142,000 1LP 42 New Mount Road, Fenton, Stoke-on-Trent, 11 £78,000 Sold Prior Staffordshire, ST4 3HQ 3 Red Bull, Market Drayton, Shropshire, TF9 12 £150,000 £186,000 LOT 5 2QS 142 Pinnox Street, Tunstall, Stoke-on- Trent, Staffordshire, ST6 6AD Wharfedale Wharf Road, Gnosall, Stafford 13 £125,000 £182,000 ST20 0DA *Guide Price £50,000 Flat 5, 63-65 Birches Head Road, Birches SOLD £52,500 14 £45,000 Unsold Head, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST1 6LH 527b King Street, Fenton, Stoke-on-Trent, 15 £63,000 Withdrawn -

English Electric Factory Makes Switch Gear and Fuse Gear, and Domestic Appli.Ances Such As {Ridges and Washing Machi.Nes

uorlrpf puz sburllrqS o^ I LL 'oN sarras lalqdrued lorluoc ,sra4JoAA Jol olnlllsul I I I l I I I I I t : -l .l ..i\l { l- Auedur cl,l ll lelouaD 3 3-33 3 Contents Page 2 1. Prelace to 2nd Edition 6 2. Foreward to 1st Editon ,l 3. Background to the OccuPation ID 4. The Facts about GEC-AEI-EE 21 5. The Role of the Government' 23 6. The Roie of the Unions. Policy for the Labour 7. The Alternative 24 Movement' 27 L New Politics, new Trade Unionism' INSTITUTE FOR WORKERS' CONTROL 45 Gambte Street Forest Road West Nottingham NG7 4ET Tel: (0602) 74504 2nd Edition 24 SePtember 1 969 1 sr Edition 1 2.SePtember 1 969 PREFACE TO SECOND EDITION So the Liverpool factory occupations are not, for the present at any rate, going to take place. Of course, there i.s widespread disappointrnent about the news that broke on September 17/1Bth just before the proposed occuparlon was due to take p1ace. The shop stewards of the GECAction Committee, with thei.r staunch allies on the District Commi_ ttee and in the 1ocal offices of the unj.ons concerned., have, in the courageous struggle, won deep admiration all over the country. From the terrific mail which has come to the offices of the Instifute Jor WorkersrControl, we can say without doubt that_sympathy for the proposed action extended throughout the whole country, and into every major industry and trade union. A body like the lnstitute, which exists to co-ordinate research and inlormation services, cannot, of course, offer any sensible advice about how particular actions should be undertaken. -

List of Selected Core Partners in CPW01 Proposed for Membership1

List of selected Core Partners in CPW01 proposed for Membership1 Core Partners and Affiliated Third Parties ITD/IADP Country (ATP) ADVANCED LABORATORY ON EMBEDDED [SYS] IT SYSTEMS S.r.L. AERNNOVA AEROSPACE S.A.U. [AIR, LPA] ES ‒ AERNNOVA ENGINEERING DIVISION ‒ [AIR, LPA] ‒ ES SAU (ATP) ‒ AERNNOVA COMPOSITES ILLESCAS ‒ [AIR, LPA] ‒ ES S.A. (ATP) ‒ AERNNOVA AEROESTRUCTURAS ‒ [AIR, LPA] ‒ ES ALAVA, S.A. (ATP) ‒ INTERNACIONAL DE COMPOSITES SA ‒ [AIR, LPA] ‒ ES (ATP) ‒ FIBERTECNIC (ATP) ‒ [AIR] ‒ ES ‒ COMPONENTES AERONAUTICOS ‒ [AIR] ‒ ES COASA, S.A. (ATP) ‒ AEROMAC MECANIZADOS ‒ [AIR] ‒ ES AERONAUTICOS SA (ATP) AEROTEX UK LLP [AIR] UK ARTUS SAS [AIR] FR CENTRO ITALIANO RICERCHE [AIR, REG] IT AEROSPAZIALI SPA CT INGENIEROS AERONAUTICOS DE [AIR] ES AUTOMOCION E INDUSTRIALES SL DEUTSCHES ZENTRUM FUER LUFT - UND [AIR, ENG, LPA] DE RAUMFAHRT EV DSPACE DIGITAL SIGNAL PROCESSING AND [SYS] DE CONTROL ENGINEERING GMBH FUNDACION ANDALUZA PARA EL [AIR] ES DESARROLLO AEROESPACIAL FUNDACION CENTRO DE TECNOLOGIAS [AIR] ES AERONAUTICAS FUNDACION PARA LA INVESTIGACION, [AIR, LPA] ES DESARROLLO Y APLICACION DE MATERIALES COMPUESTOS FUNDACION TECNALIA RESEARCH & [AIR] ES INNOVATION GE AVIO SRL [ENG, FRC] IT ‒ GE AVIATION CZECH S.R.O. ‒ [ENG] ‒ CZ ‒ POLONIA AERO SP. Z O.O. ‒ [LPA, FRC] ‒ PL LABORATORIUM BADAŃ NAPĘDÓW 1 Disclaimer: The selected participating affiliates (ATP) of Core Partners in the meaning of Clean Sky 2 Joint Undertaking Regulation n° 558/2014 shall be considered Members upon signature of the letter of endorsement of the Statutes. CS-GB-2015-06-23 doc8 CPW01 Accession_Acceptance of membership Page 1 of 2 Core Partners and Affiliated Third Parties ITD/IADP Country (ATP) LOTNICZYCH (ATP) ‒ GENERAL ELECTRIC DEUTSCHLAND ‒ [ENG, FRC, ‒ DE HOLDING GMBH (ATP) LPA] ‒ GE AVIATION SYSTEMS LTD (ATP) ‒ [ENG] ‒ UK ‒ GECP – General Electric Company Polska ‒ [ENG, FRC] ‒ PL Sp.