EDITOR's INTRODUCTION Ahmad Fauzi Abdul Hamid1 and Muhamad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Najib's Fork-Tongue Shows Again: Umno Talks of Rejuvenation Yet Oldies Get Plum Jobs at Expense of New Blood

NAJIB'S FORK-TONGUE SHOWS AGAIN: UMNO TALKS OF REJUVENATION YET OLDIES GET PLUM JOBS AT EXPENSE OF NEW BLOOD 11 February 2016 - Malaysia Chronicle The recent appointments of Tan Sri Annuar Musa, 59, as Umno information chief, and Datuk Seri Ahmad Bashah Md Hanipah, 65, as Kedah menteri besar, have raised doubts whether one of the oldest parties in the country is truly committed to rejuvenating itself. The two stalwarts are taking over the duties of younger colleagues, Datuk Ahmad Maslan, 49, and Datuk Seri Mukhriz Mahathir, 51, respectively. Umno’s decision to replace both Ahmad and Mukhriz with older leaders indicates that internal politics trumps the changes it must make to stay relevant among the younger generation. In a party where the Youth chief himself is 40 and sporting a greying beard, Umno president Datuk Seri Najib Razak has time and again stressed the need to rejuvenate itself and attract the young. “Umno and Najib specifically have been saying about it (rejuvenation) for quite some time but they lack the political will to do so,” said Professor Dr Arnold Puyok, a political science lecturer from Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. “I don’t think Najib has totally abandoned the idea of ‘peremajaan Umno’ (rejuvenation). He is just being cautious as doing so will put him in a collision course with the old guards.” In fact, as far back as 2014, Umno Youth chief Khairy Jamaluddin said older Umno leaders were unhappy with Najib’s call for rejuvenation as they believed it would pit them against their younger counterparts. He said the “noble proposal” that would help Umno win elections could be a “ticking time- bomb” instead. -

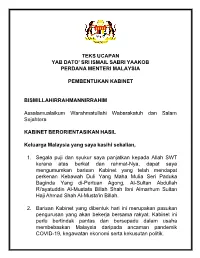

Teks-Ucapan-Pengumuman-Kabinet

TEKS UCAPAN YAB DATO’ SRI ISMAIL SABRI YAAKOB PERDANA MENTERI MALAYSIA PEMBENTUKAN KABINET BISMILLAHIRRAHMANNIRRAHIM Assalamualaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh dan Salam Sejahtera KABINET BERORIENTASIKAN HASIL Keluarga Malaysia yang saya kasihi sekalian, 1. Segala puji dan syukur saya panjatkan kepada Allah SWT kerana atas berkat dan rahmat-Nya, dapat saya mengumumkan barisan Kabinet yang telah mendapat perkenan Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong, Al-Sultan Abdullah Ri'ayatuddin Al-Mustafa Billah Shah Ibni Almarhum Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah Al-Musta'in Billah. 2. Barisan Kabinet yang dibentuk hari ini merupakan pasukan pengurusan yang akan bekerja bersama rakyat. Kabinet ini perlu bertindak pantas dan bersepadu dalam usaha membebaskan Malaysia daripada ancaman pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi serta kekusutan politik. 3. Umum mengetahui saya menerima kerajaan ini dalam keadaan seadanya. Justeru, pembentukan Kabinet ini merupakan satu formulasi semula berdasarkan situasi semasa, demi mengekalkan kestabilan dan meletakkan kepentingan serta keselamatan Keluarga Malaysia lebih daripada segala-galanya. 4. Saya akui bahawa kita sedang berada dalam keadaan yang getir akibat pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi dan diburukkan lagi dengan ketidakstabilan politik negara. 5. Berdasarkan ramalan Pertubuhan Kesihatan Sedunia (WHO), kita akan hidup bersama COVID-19 sebagai endemik, yang bersifat kekal dan menjadi sebahagian daripada kehidupan manusia. 6. Dunia mencatatkan kemunculan Variant of Concern (VOC) yang lebih agresif dan rekod di seluruh dunia menunjukkan mereka yang telah divaksinasi masih boleh dijangkiti COVID- 19. 7. Oleh itu, kerajaan akan memperkasa Agenda Nasional Malaysia Sihat (ANMS) dalam mendidik Keluarga Malaysia untuk hidup bersama virus ini. Kita perlu terus mengawal segala risiko COVID-19 dan mengamalkan norma baharu dalam kehidupan seharian. -

Malaysian Prime Minister Hosted by HSBC at Second Belt and Road Forum

News Release 30 April 2019 Malaysian Prime Minister hosted by HSBC at second Belt and Road Forum Peter Wong, Deputy Chairman and Chief Executive, the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, together with Stuart Milne, Chief Executive Officer, HSBC Malaysia, hosted a meeting for a Malaysian government delegation led by Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, Prime Minister of Malaysia, with HSBC’s Chinese corporate clients. The meeting took place in Beijing on the sidelines of the Second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, in which Mr. Wong represented HSBC. Dr. Mahathir together with the Malaysian Ministers met with Mr. Wong and executives from approximately 20 Chinese companies to discuss opportunities in Malaysia in relation to the Belt and Road Initiative. Also present at the meeting were Saifuddin Abdullah, Minister of Foreign Affairs; Mohamed Azmin Ali, Minister of Economic Affairs; Darell Leiking, Minister of International Trade and Industry; Anthony Loke, Minister of Transport; Zuraida Kamaruddin, Minister of Housing and Local Government; Salahuddin Ayub, Minister of Agriculture and Agro- Based Industry; and Mukhriz Mahathir, Chief Minister of Kedah. Ends/more Media enquiries to: Marlene Kaur +603 2075 3351 [email protected] Joanne Wong +603 2075 6169 [email protected] About HSBC Malaysia HSBC's presence in Malaysia dates back to 1884 when the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited (a company under the HSBC Group) established its first office in the country, on the island of Penang, with permission to issue currency notes. HSBC Bank Malaysia Berhad was locally incorporated in 1984 and is a wholly-owned subsidiary of The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited. -

Mw Singapore

VOLUME 4, ISSUE 2 JUNE – DECEMBER 2018 MW SINGAPORE NEWSLETTER OF THE HIGH COMMISSION OF MALAYSIA IN SINGAPORE OFFICIAL VISIT OF PRIME MINISTER YAB TUN DR MAHATHIR MOHAMAD TO SINGAPORE SINGAPORE, NOV 12: YAB Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad undertook an official visit to Singapore, at the invitation of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Singapore, His Excellency Lee Hsien Loong from 12 to 13 November 2018, followed by YAB Prime Minister’s participation at the 33rd ASEAN Summit and Relat- ed Summits from 13 to 15 November 2018. The official visit was part of YAB Prime Minister’s high-level introductory visits to ASEAN countries after being sworn in as the 7th Prime Minister of Malaysia. YAB Tun Dr Mahathir was accompanied by his wife YABhg Tun Dr Siti Hasmah Mohd Ali; Foreign Minister YB Dato’ Saifuddin Abdullah; Minister of Economic Affairs YB Dato’ Seri Mohamed Azmin Ali and senior offi- cials from the Prime Minister’s Office as well as Wisma Putra. YAB Prime Minister’s official programme at the Istana include the Welcome Ceremony (inspection of the Guards of Honour), courtesy call on President Halimah Yacob, four-eyed meeting with Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong which was followed by a Delegation Meeting, Orchid-Naming ceremony i.e. an orchid was named Dendrobium Mahathir Siti Hasmah in honour of YAB Prime Minister and YABhg. Tun Dr Siti Hasmah Mohd Ali, of which the pro- grammes ended with an official lunch hosted by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and Mrs Lee. During his visit, YAB Prime Minister also met with the members of Malaysian diaspora in Singapore. -

Foreign and Security Policy in the New Malaysia

Foreign and security policy in Elina Noor the New Malaysia November 2019 FOREIGN AND SECURITY POLICY IN THE NEW MALAYSIA The Lowy Institute is an independent policy think tank. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia — economic, political and strategic — and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high-quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Analyses are short papers analysing recent international trends and events and their policy implications. The views expressed in this paper are entirely the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute or the institutions with which the author is affiliated. FOREIGN AND SECURITY POLICY IN THE NEW MALAYSIA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Malaysia’s historic changE oF govErnment in May 2018 rEturnEd Former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad to ofFice supported by an eclectic coalition of parties and interests under the Pakatan Harapan (AlliancE of HopE) bannEr. This raisEd quEstions about how thE sElF-declared Malaysia Baharu (NEw Malaysia) would EngagE with thE rest of thE world. AftEr thE ElEction, it was gEnErally assumEd that Malaysia’s ForEign policy would largEly stay thE coursE, with some minor adjustments. This trajEctory was confirmEd with thE SEptembEr 2019 relEasE of thE Foreign Policy Framework of the New Malaysia: Change in Continuity, thE country’s First major Foreign policy restatement under the new government. -

Malaysia Politics

March 10, 2020 Malaysia Politics PN Coalition Government Cabinet unveiled Analysts PM Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin unveiled his Cabinet with no DPM post and replaced by Senior Ministers, and appointed a banker as Finance Minister. Suhaimi Ilias UMNO and PAS Presidents are not in the lineup. Cabinet formation (603) 2297 8682 reduces implementation risk to stimulus package. Immediate challenges [email protected] are navigating politics and managing economy amid risk of a no Dr Zamros Dzulkafli confidence motion at Parliament sitting on 18 May-23 June 2020 and (603) 2082 6818 economic downsides as crude oil price slump adds to the COVID-19 [email protected] outbreak. Ramesh Lankanathan No DPM but Senior Ministers instead; larger Cabinet (603) 2297 8685 reflecting coalition makeup; and a banker as [email protected] Finance Minister William Poh Chee Keong Against the long-standing tradition, there is no Deputy PM post in this (603) 2297 8683 Cabinet. The Constitution also makes no provision on DPM appointment. [email protected] ECONOMICS Instead, Senior Minister status are assigned to the Cabinet posts in charge of 1) International Trade & Industry, 2) Defence, 3) Works, and 4) Education portfolios. These Senior Minister posts are distributed between what we see as key representations in the Perikatan Nasional (PN) coalition i.e. former PKR Deputy President turned independent Datuk Seri Azmin Ali (International Trade & Industry), UMNO Vice President Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob (Defence), Gabungan Parti Sarawak (GPS) Chief Whip Datuk Seri Fadillah Yusof (Works) and PM’s party Parti Pribumi Malaysia Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu) Supreme Council member Dr Mohd Radzi Md Jidin (Education). -

Federal Government of Malaysia Cabinet Members 2013

Federal Government of Malaysia Cabinet Members 2013 PRIME MINISTER MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND HIGHER YAB Dato’ Sri Haji Mohd. Najib Bin Tun Haji Abdul Razak EDUCATION MINISTER I : YAB Tan Sri Dato’ Haji Muhyiddin Bin DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER Mohd. Yassin YAB Tan Sri Dato’ Haji Muhyiddin Bin Mohd. Yassin MINISTER II : YB Dato’ Seri Haji Idris Bin Jusoh DEPUTY MINISTER I : YB Datuk Mary Yap Kain Ching PRIME MINISTER’S DEPARTMENT DEPUTY MINISTER II : YB Tuan P. Kamalanathan A/L P. MINISTER : YB Mejar Jeneral Dato’ Seri Jamil Khir Bin Panchanathan Baharom YB Senator Dato’ Sri Idris Jala MINISTRY OF DEFENCE YB Tan Sri Datuk Seri Panglima Joseph MINISTER : YB Dato’ Seri Hishammuddin Bin Tun Kurup Hussein YB Datuk Joseph Entulu Anak Belaun DEPUTY MINISTER : YB Datuk Abd Rahim Bin Bakri YB Dato’ Seri Shahidan Bin Kassim YB Senator Dato’ Sri Abdul Wahid Bin MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT Omar MINISTER (ACTING) : YB Dato’ Seri Hishammuddin Bin Tun YB Senator Datuk Paul Low Seng Kwan Hussein YB Puan Hajah Nancy Binti Shukri DEPUTY MINISTER : YB Datuk Ab. Aziz Bin Kaprawi DEPUTY MINISTER : YB Dato’ Razali Hj. Ibrahim YB Senator Tuan Waytha Moorthy MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS Ponnusamy MINISTER : YB Dato’ Seri Dr. Ahmad Zahid Bin Hamidi MINISTRY OF FINANCE DEPUTY MINISTER : YB Datuk Dr. Wan Junaidi Bin Tuanku MINISTER I : YAB Dato’ Sri Haji Mohd. Najib Bin Tun Haji Jaafar Abdul Razak MINISTER II : YB Dato’ Seri Ahmad Husni Bin Mohamad MINISTRY OF WORKS Hanadzlah MINISTER : YB Datuk Haji Fadillah Bin Yusof DEPUTY MINISTER : YB Datuk Haji Ahmad Bin Haji Maslan DEPUTY MINISTER : YB Datuk Rosnah Binti Haji Abdul Rashid Shirlin MINISTRY OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND MINISTRY OF FEDERAL TERRITORIES INDUSTRY MINISTER : YB Datuk Seri Tengku Adnan Bin Tengku MINISTER : YB Dato’ Sri Mustapa Bin Mohamed Mansor DEPUTY MINISTER : YB Tuan Ir. -

The Straits Times, Wednesday, June 12, 2019

A12 WORLD | THE STRAITS TIMES | WEDNESDAY, JUNE 12, 2019 | Retired general Kivlan Zen, who is in police Ex-general behind Jakarta custody, was allegedly behind the plot to kill four senior state officials and assassination plot: Police a high-profile pollster. PHOTO: KIVLAN ZEN/FACEBOOK Protesters Second suspect, believed to be shooting fireworks at involved in procurement of police during firearms, said to be PPP politician clashes in Jakarta last month. Francis Chan According to Indonesia Bureau Chief statements of In Jakarta suspected hitmen currently in police Retired Indonesian army general custody, the Kivlan Zen was behind the plot to assassinations assassinate four senior state offi- were supposed cials, as well as a high-profile poll- to take place ster, during the riots in Jakarta last amid the chaos month, said the police yesterday. of the riots. At a press conference, Adjunct ST PHOTO: Chief Police Commissioner Ade Ary ARIFFIN JAMAR Syam Indradi disclosed that a local politician with the initials HM was also involved in the procurement of firearms for the alleged hit. Indonesian police typically do not name suspects in ongoing inves- tigations, but several local media reports identified the politician as United Development Party (PPP) cadre member Habil Marati. The PPP is one of nine political parties that nominated President Joko Widodo for re-election. Both men are now in police cus- tody pending further investiga- tions, said Commissioner Ade, who is Jakarta police deputy director for general criminal investigations. “Based on facts, the testimony of witnesses and evidence, they con- mand and a close ally of presiden- FIVE TARGETS ON HIT LIST ments indicate that he had master- rupiah to conduct surveillance as sorted to direct the premeditated tial candidate Prabowo Subianto. -

Malaysia and Singapore - Cpa Uk Diplomatic Visit Report Summary 17 - 20 February 2020

MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE - CPA UK DIPLOMATIC VISIT REPORT SUMMARY 17 - 20 FEBRUARY 2020 PROGRAMME OVERVIEW From 17-20 February 2020, a four-member Commonwealth Parliamentary Association UK (CPA UK) cross-party delegation visited Malaysia and Singapore for a diplomatic visit. Against the backdrop of the Covid-19 outbreak, this visit proved to be unique in so many ways. The visit focused on four key themes; trade, economic links, human rights and civil liberties and defence and security. Although Malaysia and Singapore have a shared history, in the context of the above themes, there are clear differences between the two countries and their respective approaches to them. Both countries still have close links to the UK and the Commonwealth and this was evident during our time in country, with clear similarities including both respective Parliaments following the Westminster committee system. This report outlines some of the key learnings from the visit. IMPACT & OUTCOMES Impact A stronger relationship between the UK, Malaysian and Singaporean Parliaments by building knowledge and understanding among parliamentarians of the issues facing the UK, Malaysia and Singapore. Outcomes a) UK parliamentarians have a deeper understanding of Malaysia’s and Singapore’s political systems and parliaments. The CPA UK delegation in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia b) UK, Malaysian and Singaporean parliamentarians PROGRAMME PARTNERS & SUPPORTERS have shared challenges and solutions in parliamentary management practice and procedure, security and reform. c) UK parliamentarians have a deeper understanding of the political landscape and current salient issues in Malaysia and Singapore. MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE - CPA UK DIPLOMATIC VISIT FULL REPORT 17 - 20 FEBRUARY 2020 CPA UK & MALAYSIA In recent years, parliamentarians from the UK and Malaysia have participated in regular activities facilitated by the CPA UK. -

Federal-State Relations Under the Pakatan Harapan Government

FEDERAL-STATE RELATIONS UNDER THE PAKATAN HARAPAN GOVERNMENT Tricia Yeoh TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS12/20s ISSUE ISBN 978-9-814951-13-5 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 12 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 4 9 5 1 1 3 5 2020 TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 20-J07166 01 Trends_2020-12.indd 1 5/10/20 2:25 PM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 20-J07166 01 Trends_2020-12.indd 2 5/10/20 2:25 PM FEDERAL-STATE RELATIONS UNDER THE PAKATAN HARAPAN GOVERNMENT Tricia Yeoh ISSUE 12 2020 20-J07166 01 Trends_2020-12.indd 3 5/10/20 2:25 PM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2020 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

Crisis Committee Issue: Transition of Power in Malaysia Student Officer

Shanghai Model United Nations XX 2018 | Research Reports Forum: Crisis Committee Issue: Transition of Power in Malaysia Student Officer: Wesley Chiu Position: Crisis Chair Mohamad Sabu (Minister of Defense) From a culinary graduate to the Minister of Defense, Mat Sabu’s rise in Malaysian politics is widely considered as one of the most bizarre journey. Sabu, unlike many other military personnel, is a charismatic and holistic leader who constantly speaks out racial and religious tensions in Malaysia. Despite not being a typical military officer, Sabu has a grand vision for the Malaysian military. With the deteriorating state of most equipments and the rapidly advancing military technology, Sabu intents to implement a whole scale change in the military by brining in drone aircrafts and introducing the use of Artificial Intelligence into the military. However, understanding that the government is currently on a tight budget, Subu recognizes that his vision might take a certain level of patience before becoming a reality. Mohamed Azmin Ali (Minister of Economic Affairs) While it is true that the Malaysian people has just elected a new Prime Minister, Mohamed Azmin Ali has been tipped to become the long-term solution to Malaysian leadership. A relatively reserved and quiet politician, Azmin has been involved in Malaysian politics for 30 years. Like many other progressive politicians in the current administration, Azmin shares the same worry about religion and racial devision. However, as the head of the Minister of Economic Affairs (a newly created ministry in the current administration), Azmin is more troubled by the economic aftermaths of failed programs such as the BR1M. -

Annual Report | 2019-20 Ministry of External Affairs New Delhi

Ministry of External Affairs Annual Report | 2019-20 Ministry of External Affairs New Delhi Annual Report | 2019-20 The Annual Report of the Ministry of External Affairs is brought out by the Policy Planning and Research Division. A digital copy of the Annual Report can be accessed at the Ministry’s website : www.mea.gov.in. This Annual Report has also been published as an audio book (in Hindi) in collaboration with the National Institute for the Empowerment of Persons with Visual Disabilities (NIEPVD) Dehradun. Designed and Produced by www.creativedge.in Dr. S Jaishankar External Affairs Minister. Earlier Dr S Jaishankar was President – Global Corporate Affairs at Tata Sons Private Limited from May 2018. He was Foreign Secretary from 2015-18, Ambassador to United States from 2013-15, Ambassador to China from 2009-2013, High Commissioner to Singapore from 2007- 2009 and Ambassador to the Czech Republic from 2000-2004. He has also served in other diplomatic assignments in Embassies in Moscow, Colombo, Budapest and Tokyo, as well in the Ministry of External Affairs and the President’s Secretariat. Dr S. Jaishankar is a graduate of St. Stephen’s College at the University of Delhi. He has an MA in Political Science and an M. Phil and Ph.D in International Relations from Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi. He is a recipient of the Padma Shri award in 2019. He is married to Kyoko Jaishankar and has two sons & and a daughter. Shri V. Muraleedharan Minister of State for External Affairs Shri V. Muraleedharan, born on 12 December 1958 in Kanuur District of Kerala to Shri Gopalan Vannathan Veettil and Smt.