Dammed by Dammed by Burma's Generals Burma's Generals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MYANMAR Full Moon Festival, Temples and Waterways

MYANMAR Full Moon Festival, Temples and Waterways Dates: Dec. 29, 2017—Jan. 10, 2018 Cost: $3,450 (Double Occupancy) Explore the rich cultural depths of this little known country from Buddhist temples to fishing communities, with the highlight of the Full Moon Festival in Bagan. !1 ! ! ! Daily Itinerary Rooted in history and rich in culture, Myanmar (formerly known as Burma) is a country filled with awe inspiring Buddhist temples and British colonial structures. The diversity of the local people can be seen with the traditional one legged fishing style on Lake Inle to the rituals of the pilgrims at the Shwedagon Pagoda. We will traverse this magnificent country, starting in the south at Yangon, and hopping to the banks of the Ayeyarwady River in Bagan for an unmatchable experience. Bagan will be the site of the Full Moon Festival where we will participate in the festivities and sample the local dishes. Then we set out on Lake Inle to see the fisherman, floating gardens and a variety of wildlife. The trip concludes in the northern city of Mandalay for once last adventure in this captivating country. Day 1 | Friday, December 29 | Yangon Upon midday arrival in Yangon, your local guide will meet and transfer you to the hotel. Once you have a chance to settle in, there will be a group orientation and an invitation to a traditional welcome dinner at the hotel. Grand United Hotel (Ahlone Branch) (D) YANGON (formerly Rangoon) is the former capital of Myanmar and largest city with nearly 7 million inhabitants. The center of political and economic power under British colonial rule, it still boasts a unique mixture of modern buildings and traditional wooden structures with numerous parks, it was known as the “Garden of the East”. -

4-Day Inle Lake and Kakku Discovery

4-Day Inle Lake and Kakku Discovery Downloaded on: 23 Sep 2021 Tour code: PKHCIKDB Tour type ( Private ) Tour Level: Relaxed / Easy Tour Comfort: Standard Tour Period: 4 Days English Heho, Inle Lake, Taunggyi, Kakku highlights tour details Full day boat tour to Indaing to see 14th -18th century pagodas During these 4 Days, explore the fascinating Inle lake and its Explore the 5-day rotating markets surrounding. You will visit the Kakku Pagoda complex near Taunggyi Visit Phaung Daw Oo Pagoda and surroundings which features a cluster of fantastic ancient monuments and is Learn how to make traditional handicrafts located in the heart of the Pao Territory. On the way up or down, stop silk weaving in local workshop in Taunggyi to visit the local market. On other days, visit the main Drive to Kakku via Taunggyi to visit a fascinating range of pagodas sites on the lake going along the floating gardens and the houses on in the Pa-O territory stilts. The fishermen and their unique way of rowing (leg rowers) are of particular interest. why choose this tour? A perfect opportunity to explore fascinating Inle Lake and its surrounding charming areas Discovering the historical background and finest architecture at Kakkku Pagodas Complex in Pa-O region Meeting with the inspiring locals aritsans to observe their traditional techniques and rural ways of life Contact [email protected] www.diethelmtravel.com Copyright © Diethelm Travel Management Limited. All right reserved. 4-Day Inle Lake and Kakku Discovery Contact [email protected] www.diethelmtravel.com Copyright © Diethelm Travel Management Limited. -

Die Karen: Ideologie, Interessen Und Kultur

Die Karen: Ideologie, Interessen und Kultur Eine Analyse der Feldforschungsberichte und Theorienbildung Magisterarbeit zur Erlangung der Würde des Magister Artium der Philosophischen Fakultäten der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität zu Freiburg i. Br. 1992 vorgelegt von Reiner Buergin aus Weil am Rhein (Ausdruck vom Februar 2000) Inhaltsverzeichnis: Einleitung 1 Thema, Ziele, Vorgehensweise 5 2 Übersicht über die Literatur 6 I Die Karen in Südostasien/Einführung 9 1 Bezeichnungen und Sprache 9 2 Verbreitung der verschiedenen Gruppen und Demographie 10 3 Wirtschaftliche Verhältnisse 12 a) Brandrodungsfeldbau 12 b) Naßreisanbau 13 c) Sonstige wirtschaftliche Tätigkeiten und ökomische Krise 14 4 Soziale und politische Organisation 15 a) Entwicklung der Siedlungsform 15 b) Familie und Haushalt 16 c) Verwandtschaftsstrukturen und -gruppen 17 d) Die Dorfgemeinschaft 17 e) Die Territorialgemeinschaft 18 f) Nationalstaatliche Integration 19 5 Religion und Weltbild 20 a) Traditionelle Religionsformen 20 b) Religiöser Wandel, Buddhismus und Christentum 21 c) Mythologie, Weltbild und Werthaltung 22 II Geschichte der verschiedenen Gruppen 1 Ursprung und Einwanderung nach Hinterindien 24 a) Ursprung der Karen 24 b) Einwanderung nach Hinterindien 25 2 Karen in Hinterindien von ca. 1200 - 1800 25 a) Sgaw und Pwo in Burma 25 b) Die Kayah 27 c) Karen in Thailand 28 3 Karen in Burma und Thailand im 19. Jh. 29 a) Sgaw und Pwo in Burma 29 b) Sgaw und Pwo in Siam 31 c) Sgaw und Pwo in Nordthailand 32 d) Die Kayah im 19. Jahrhundert 33 2 4 Karen in Burma und Thailand -

BURMA (MYANMAR) COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

BURMA (MYANMAR) COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service 17 June 2011 BURMA (MYANMAR) 17 JUNE 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN BURMA FROM 16 MAY TO 17 JUNE 2011 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON BURMA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 16 MAY AND 17 JUNE 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY (INDEPENDENCE (1948) – NOVEMBER 2010) ................................................ 3.01 Constitutional referendum – 2008....................................................................... 3.03 Build up to 2010 elections ................................................................................... 3.05 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS (NOVEMBER 2010 – MARCH 2011)....................................... 4.01 November 2010 elections .................................................................................... 4.01 Release of Aung San Suu Kyi ............................................................................. 4.13 Opening of Parliament ......................................................................................... 4.16 5. CONSTITUTION......................................................................................................... -

Legends of the Golden Land the Road

The University of North Carolina General Alumni Association LLegendsegends ooff thethe GGoldenolden LLandand aandnd tthehe RRoadoad ttoo MMandalayandalay with UNC’s Peter A. Coclanis February 10 to 22, 2014 ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Dear Carolina Alumni and Friends: Myanmar, better known as Burma, has recently re-emerged from isolation after spending decades locked away from the world. Join fellow Tar Heels and friends and be among the fi rst Americans to experience this golden land of deeply spiritual Buddhist beliefs, old world traditions and more than one million pagodas. You will become immersed in the country’s rich heritage, the incredible beauty of its landscape and the warmth of friendly people who take great pride in welcoming you to their ancient and enchanting land. Breathtaking moments await you amid the lush greenery and golden plains as you discover great kingdoms that have risen and fallen through thousands of years of history. See the legacy of Britain’s former colony in its architecture and tree-lined boulevards, and the infl uences of China, India and Thailand evident in the art, dance and dress of Myanmar today. Observe and interact with skilled artisans who practice the traditional arts of textile weaving, goldsmithing, lacquerware and wood carving. Meet fascinating people, local experts and musicians who will enhance your experience with educational lectures and insightful presentations. And, along the streets and in the markets you will sense the metta bhavana, the culture of loving kindness that the Burmese extend to you, their special guest. This comprehensive itinerary features colonial Yangon, the archaeological sites of Bagan, the palace of Mandalay and the exquisite Inle Lake, with forays along the fabled Irrawaddy River. -

Adoption of Small-Scale Aquaculture Technologies by Smallholder Farmers in Myanmar; Challenges and Opportunities

Adoption of small-scale aquaculture technologies by smallholder farmers in Myanmar; challenges and opportunities Manjurul Karim, Kimio Leemans WorldFish, Myanmar PRESENTATION STRUCTURE • WorldFish • MYCulture project • Geographical focus • Key interventions • Key findings from PAR and conclusion • Shan Aquaculture • Way forward WorldFish’s mission and geographic focus Our goal is to reduce poverty and hunger by India improving fisheries and aquaculture Timor-leste MYCulture Project objectives •Promoting SSA to increase income and improve nutrition in Myanmar Donors and Partners Donor PARTNERS 1. PARTNERS Map of project areas Townships • Bogalae • Pyapon • Mawgyun • Dedaye • Zalon State and region • Kyaiklat • Kayin State • Yinmarbin • Bago Region • Meiktila • Mon State • Pale • Nay Pyi Taw • Maubin • Central Dry Zone • Ottayathiri • Ayeyarwady region • Poppathiri • Thaton • Paung • Hpaan • Waw Study objective and methods - Assessing performance of aquaculture technologies promoted by the project Tools used Participatory Community Appraisal to learn about current situation and local preferences Study participants : 649 farmers from 76 villages Cultured species No. of Treatments: 29 Treatment ID Fish species (mono and polyculture mixes) T1 (n=94) Tilapia T2 (n=44) Rohu T21 (n=37) Rohu + (mrigal) + (catla) T22 (n=63) Rohu + mrigal T3 (n=52) Pangasius T32 (n=26) Pangasius + rohu T4 (n=74) Mola + (tilapia) + (rohu) + mrigal T5 (n=22) Silver Barb T51 (n=21) Silver Barb + rohu + mrigal Total = 423 Resources identified for SSA Chan Myaung Ponds -

Inle Lake Long Term Restoration & Conservation Plan

Foreword Inle Lake is one of the priority conservation areas in Myanmar due to its unique ecology, historical, religious, cultural, traditional background and natural beauty. It is one of the most popular tourist destinations in Myanmar and tourism is expected to rise significantly with the opening up of the country. Realization that widespread soil erosion on the mountain ranges flanking Inle Lake could eventually cause problems that would threaten the future existence of the Lake prevailed since late 19th century. Measures were introduced, but were ineffective as they were not developed progressively enough. Several droughts occurred since 1989, but the severe drought that occurred in 2010 was the wakeup call, which brought about serious concerns and recognition that urgent planning and mitigation measures in a comprehensive and integrated manner was imperative, if the Lake was to be saved. Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry (MOECAF) organized a National Workshop in 2011 at Nay Pyi Taw; basic elements required to draw up a Long Term Action Plan were identified and a resolution to formulate a Long Term Restoration and Conservation Plan for Inle Lake was adopted. MOECAF requested UN-Habitat to assist in formulation of the Long Term Restoration and Conservation Plan for Inle Lake and the Royal Norwegian Government kindly provided necessary financial assistance. The Team of experts engaged by UN-Habitat identified the main causes, both natural and human induced, that have impacted adversely on the Lake and its environment. Fall out of climatic variations, irresponsible clearing of soil cover, various forms of change in land use patterns in the Watershed areas caused widespread soil erosion, resulting in heavy loads of sediment entering the main feeder streams and ultimately into the Lake, causing it to become very much smaller in size and shallower in depth. -

Ethnic Armed Actors and Justice Provision in Myanmar

Ethnic Armed Actors and Justice Provision in Myanmar Brian McCartan and Kim Jolliffe October 2016 Preface As a result of decades of ongoing civil war, large areas of Myanmar remain outside government rule, or are subject to mixed control and governance by the government and an array of ethnic armed actors (EAAs). These included ethnic armed organizations, with ceasefires or in conflict with the state, as well as state-backed ethnic paramilitary organizations, such as the Border Guard Forces and People’s Militia Forces. Despite this complexity, order has been created in these areas, in large part through customary justice mechanisms at the community level, and as a result of justice systems administered by EAAs. Though the rule of law and the workings of Myanmar’s justice system are receiving increasing attention, the role and structure of EAA justice systems and village justice remain little known and therefore, poorly understood. As such, The Asia Foundation is pleased to present this research on justice provision and ethnic armed actors in Myanmar, as part of the Foundation’s Social Services in Contested Areas in Myanmar series. The study details how the village, and village-based mechanisms, are the foundation of stability and order for civilians in most of these areas. These systems have then been built through EAA justice systems, which maintain a hierarchy of courts above the village level. Understanding the continuity and stability of these village systems, and the heterogeneity of the EAA justice systems which work alongside them, is essential for understanding civilians’ experiences of justice and security across Myanmar, as well as the opportunities for positive change that exist in Myanmar’s ongoing peace process and governance reforms. -

Sold to Be Soldiers the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma

October 2007 Volume 19, No. 15(C) Sold to be Soldiers The Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma Map of Burma........................................................................................................... 1 Terminology and Abbreviations................................................................................2 I. Summary...............................................................................................................5 The Government of Burma’s Armed Forces: The Tatmadaw ..................................6 Government Failure to Address Child Recruitment ...............................................9 Non-state Armed Groups....................................................................................11 The Local and International Response ............................................................... 12 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................. 14 To the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) ........................................ 14 To All Non-state Armed Groups.......................................................................... 17 To the Governments of Thailand, Laos, Bangladesh, India, and China ............... 18 To the Government of Thailand.......................................................................... 18 To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)....................... 18 To UNICEF ........................................................................................................ -

Northern Thailand

© Lonely Planet Publications 339 Northern Thailand The first true Thai kingdoms arose in northern Thailand, endowing this region with a rich cultural heritage. Whether at the sleepy town of Lamphun or the famed ruins of Sukhothai, the ancient origins of Thai art and culture can still be seen. A distinct Thai culture thrives in northern Thailand. The northerners are very proud of their local customs, considering their ways to be part of Thailand’s ‘original’ tradition. Look for symbols displayed by northern Thais to express cultural solidarity: kàlae (carved wooden ‘X’ motifs) on house gables and the ubiquitous sêua mâw hâwm (indigo-dyed rice-farmer’s shirt). The north is also the home of Thailand’s hill tribes, each with their own unique way of life. The region’s diverse mix of ethnic groups range from Karen and Shan to Akha and Yunnanese. The scenic beauty of the north has been fairly well preserved and has more natural for- est cover than any other region in Thailand. It is threaded with majestic rivers, dotted with waterfalls, and breathtaking mountains frame almost every view. The provinces in this chapter have a plethora of natural, cultural and architectural riches. Enjoy one of the most beautiful Lanna temples in Lampang Province. Explore the impressive trekking opportunities and the quiet Mekong river towns of Chiang Rai Province. The exciting hairpin bends and stunning scenery of Mae Hong Son Province make it a popular choice for trekking, river and motorcycle trips. Home to many Burmese refugees, Mae Sot in Tak Province is a fascinating frontier town. -

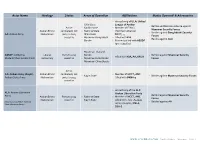

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

Decentralization, Empowerment and Tourism Development:Pai Title Town in Mae Hong Son, Thailand

Decentralization, Empowerment and Tourism Development:Pai Title Town in Mae Hong Son, Thailand Author(s) LORTANAVANIT, Duangjai Citation 東南アジア研究 (2009), 47(2): 150-179 Issue Date 2009-09-30 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/108385 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 47, No. 2, September 2009 Decentralization, Empowerment and Tourism Development: Pai Town in Mae Hong Son, Thailand Duangjai LORTANAVANIT* Abstract In the once-remote valley of Pai in Mae Hong Son Province in northwestern Thailand, tourism has been a powerful force shaping dramatic changes. However, tourism is a complex subject involving a range of actors and actions both within and outside the valley. It has occurred simultaneously with other trans- formational processes in Thai society. This paper focuses on Viengtai, the market and administrative center of Pai District, drawing on observations made from 1997 to the present, including dissertation field work in 2005 and 2006. This study seeks to describe and interpret processes and practices at work in Pai, where a range of social actors compete and negotiate over resources and notions of culture and locality, with an emphasis on political decentralization. It will describe the interaction between actors in resource management for tourism development in Pai from the 1980s to the present. It describes the distinct fea- tures of the negotiations and conflicts regarding resources and notions of culture and locality among local communities, entrepreneurs, tourists, NGOs, and state and local administration in the era of political decentralization in Thailand. Keywords: community tourism, empowerment, decentralization I Introduction Tourism is a leading foreign exchange earner of the Thai economy, and has been the focus of investment, state policy and media attention in recent decades.