Siege of Beirut Would Resurface

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10 Ecosy Congress

10 TH ECOSY CONGRESS Bucharest, 31 March – 3 April 2011 th Reports of the 9 Mandate ECOSY – Young European Socialists “Talking about my generation” CONTENTS Petroula Nteledimou ECOSY President p. 3 Janna Besamusca ECOSY Secretary General p. 10 Brando Benifei Vice President p. 50 Christophe Schiltz Vice President p. 55 Kaisa Penny Vice President p. 57 Nils Hindersmann Vice President p. 60 Pedro Delgado Alves Vice President p. 62 Joan Conca Coordinator Migration and Integration network p. 65 Marianne Muona Coordinator YFJ network p. 66 Michael Heiling Coordinator Pool of Trainers p. 68 Miki Dam Larsen Coordinator Queer Network p. 70 Sandra Breiteneder Coordinator Feminist Network p. 71 Thomas Maes Coordinator Students Network p. 72 10 th ECOSY Congress 2 Held thanks to hospitality of TSD Bucharest, Romania 31 st March - 3 rd April 2011 9th Mandate reports ECOSY – Young European Socialists “Talking about my generation” Petroula Nteledimou, ECOSY President Report of activities, 16/04/2009 – 01/04/2011 - 16-19/04/2009 : ECOSY Congress , Brussels (Belgium). - 24/04/2009 : PES Leaders’ Meeting , Toulouse (France). Launch of the PES European Elections Campaign. - 25/04/2009 : SONK European Elections event , Helsinki (Finland). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. - 03/05/2009 : PASOK Youth European Elections event , Drama (Greece). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. - 04/05/2009 : Greek Women’s Union European Elections debate , Kavala (Greece). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. - 07-08/05/2009 : European Youth Forum General Assembly , Brussels (Belgium). - 08/05/2009 : PES Presidency meeting , Brussels (Belgium). - 09-10/05/2009 : JS Portugal European Election debate , Lisbon (Portugal). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. -

US Foreign Policy and the Multinational Force in Lebanon, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-53973-7 256 BIBLIOGRAPHY

BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCE ARCHIVES Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, Simi Valley Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library. Abilene James Earl Carter Presidential Library, Atlanta United Nations Archives and Record Management, New York City The British National Archives, Kew Central Intelligence Agency Freedom of Information Archives, Online Department of State Freedom of Information ‘Released Documents’ Archive, Online PUBLISHED INTERVIEWS Interview with Fawaaz Traboulsi by Lynn Barbee, Published in MERIP Reports, No.61, October 1970, pp.3–5. Interview with Shaykh Muhammad Husayn Fadlallah by Mahmoud Soueid, Published in Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol.25, No.1, 1995. Interview with Yusif al-Haytham, Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, Published in MERIP Reports, No. 44 February 1976. Speech given by Fawwaz Traboulsi and Assaf Kfoury ‘Lebanon on the Brink’ Lebanese American University, 18 January 2007. Interview with Prince Farid Chehab, Former Director of Public Security, Centre for Arab and Middle Eastern Studies, American University of Beirut, 2007. © The Author(s) 2017 255 C. Varady, US Foreign Policy and the Multinational Force in Lebanon, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-53973-7 256 BIBLIOGRAPHY Interview with Adel Osseiran, President of the Council of Representatives, Lebanon, Centre for Arab and Middle Eastern Studies, American University of Beirut, 2007. Interview with Said Akl, Lebanese Writer and Political Poet, Centre for Arab and Middle Eastern Studies, American University of Beirut, 2007. Interview with Anbara Salam al Khalidi, Conducted by Laila Rostom, Centre for Arab and Middle Eastern Studies, American University of Beirut, 2007. Interview with Raymond Edde, Former Lebanese Presidential Candidate and Former State Ministers, Jan 25 1970, Centre for Arab and Middle Eastern Studies, American University of Beirut, 2007. -

THE PLO and the PALESTINIAN ARMED STRUGGLE by Professor Yezid Sayigh, Department of War Studies, King's College London

THE PLO AND THE PALESTINIAN ARMED STRUGGLE by Professor Yezid Sayigh, Department of War Studies, King's College London The emergence of a durable Palestinian nationalism was one of the more remarkable developments in the history of the modern Middle East in the second half of the 20th century. This was largely due to a generation of young activists who proved particularly adept at capturing the public imagination, and at seizing opportunities to develop autonomous political institutions and to promote their cause regionally and internationally. Their principal vehicle was the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), while armed struggle, both as practice and as doctrine, was their primary means of mobilizing their constituency and asserting a distinct national identity. By the end of the 1970s a majority of countries – starting with Arab countries, then extending through the Third World and the Soviet bloc and other socialist countries, and ending with a growing number of West European countries – had recognized the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. The United Nations General Assembly meanwhile confirmed the right of the stateless Palestinians to national self- determination, a position adopted subsequently by the European Union and eventually echoed, in the form of support for Palestinian statehood, by the United States and Israel from 2001 onwards. None of this was a foregone conclusion, however. Britain had promised to establish a Jewish ‘national home’ in Palestine when it seized the country from the Ottoman Empire in 1917, without making a similar commitment to the indigenous Palestinian Arab inhabitants. In 1929 it offered them the opportunity to establish a self-governing agency and to participate in an elected assembly, but their community leaders refused the offer because it was conditional on accepting continued British rule and the establishment of the Jewish ‘national home’ in what they considered their own homeland. -

Militia Politics

INTRODUCTION Humboldt – Universität zu Berlin Dissertation MILITIA POLITICS THE FORMATION AND ORGANISATION OF IRREGULAR ARMED FORCES IN SUDAN (1985-2001) AND LEBANON (1975-1991) Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil) Philosophische Fakultät III der Humbold – Universität zu Berlin (M.A. B.A.) Jago Salmon; 9 Juli 1978; Canberra, Australia Dekan: Prof. Dr. Gert-Joachim Glaeßner Gutachter: 1. Dr. Klaus Schlichte 2. Prof. Joel Migdal Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 18.07.2006 INTRODUCTION You have to know that there are two kinds of captain praised. One is those who have done great things with an army ordered by its own natural discipline, as were the greater part of Roman citizens and others who have guided armies. These have had no other trouble than to keep them good and see to guiding them securely. The other is those who not only have had to overcome the enemy, but, before they arrive at that, have been necessitated to make their army good and well ordered. These without doubt merit much more praise… Niccolò Machiavelli, The Art of War (2003, 161) INTRODUCTION Abstract This thesis provides an analysis of the organizational politics of state supporting armed groups, and demonstrates how group cohesion and institutionalization impact on the patterns of violence witnessed within civil wars. Using an historical comparative method, strategies of leadership control are examined in the processes of organizational evolution of the Popular Defence Forces, an Islamist Nationalist militia, and the allied Lebanese Forces, a Christian Nationalist militia. The first group was a centrally coordinated network of irregular forces which fielded ill-disciplined and semi-autonomous military units, and was responsible for severe war crimes. -

Fatah and Hamas: the New Palestinian Factional Reality

Order Code RS22395 March 3, 2006 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Fatah and Hamas: the New Palestinian Factional Reality Aaron D. Pina Analyst in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary For the first time in its history, the Palestinian parliament is set to be led by Hamas, which the United States and European Union have designated a foreign terrorist organization. Although some lauded the generally free and fair election in January 2006, others criticized the outcome and accused Hamas of “hijacking” democracy. This report provides an overview of the new political realities in the West Bank and Gaza after the election, the challenges Fatah and Hamas face, and possible implications for U.S. policy. This report will be updated as warranted. For more information on the Palestinians, see CRS Report RL33269, Palestinian Elections, by Aaron D. Pina, CRS Issue Brief IB91137 The Middle East Peace Talks, by Carol Migdalovitz, and CRS Report RS22370, U.S. Assistance to the Palestinians, by Jeremy M. Sharp. Background On January 25, 2006, Palestinians voted in parliamentary elections and Hamas emerged as the clear winner, with 74 out of 132 parliamentary seats. Fatah, the dominant party in the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), won 45 seats, and 13 seats went to other minor parties. Since then, several governments, including the United States, have cautioned that unless Hamas disavows terrorism, recognizes Israel, and accepts all previous Israeli-Palestinian agreements, diplomatic and economic relations with the Palestinian Authority may be circumscribed or ended altogether. Hamas1 During the 1970s and 1980s, Palestinians experienced a rise in political Islam, embodied in Hamas, founded in 1987 by the late Sheik Ahmad Yasin. -

THE CHALLENGE of GAZA: Policy Options and Broader Implications

BROOKINGS 1775 Massachusetts Ave., NW Washington, D.C. 20036-2103 www.brookings.edu ANALYSIS PAPER Number 23, July 2011 THE CHALLENGE OF GAZA: Policy Options and Broader Implications Daniel Byman Gad Goldstein ANALYSIS PAPER Number 23, July 2011 THE CHALLENGE OF GAZA: Policy Options and Broader Implications Daniel Byman Gad Goldstein The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined by any donation. Copyright © 2011 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 www.brookings.edu Table of Contents Executive Summary . iv Acknowledgements . ix The Authors . x Introduction . 1 The Nature of the Challenge in Gaza . 3 Factors Beyond Gaza to Consider . 18 Policy Options . 24 THE CHALLENGE OF GAZA: Policy Options and Broader Implications The Saban Center at BRooKings iii Executive Summary lthough both the United States and Israel Hamas draws on many resources to stay in power . devote tremendous attention to the Middle Most notably, Hamas has long exploited its infra- East peace process, the Gaza Strip and its structure of mosques, social services, and communi- HamasA government have continued to vex Ameri- ty organizations to raise money and attract recruits . -

Legitimization of Terrorism by Fatah and the Palestinian Authority

רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ" ) רמה כרמ כ ז ז מל מה ו י תשר עד מל מה ו ד ו י ד ע י י ע ן י ן ו ל ( רט למ ו מ" ר ) כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ול רט ו רור Legitimization of Terrorism by Fatah and the Palestinian Authority: Glorification of the Murder of the Israeli Athletes at the Munich Olympic Games November 11, 2018 Overview On September 5, 2018, the anniversary of the terrorist attack at the 1972 Munich Olympics was marked, in which 11 Israelis were murdered1. The Fatah Movement, which carried out the terrorist attack, mentioned the anniversary of the event in posts posted on its official Facebook pages. These posts glorified the attack (“a high-quality military operation”) and praised its perpetrators. The terrorists who carried out the murder are referred to in the post of the Fatah Movement in Nablus as “the heroes of the Munich operation;” and in the post of the Fatah Movement in Bethlehem they are referred to as “heroes of the Fatah Movement, sons of Yasser [Arafat].” The portrayal of the terrorist attack in Munich is also expressed favorably in a Palestinian Authority history textbook, in which the murder is described as an act carried out by Fedayeen (who sacrifice their lives by carrying out a military operation) with the aim of “attacking Israeli interests abroad” (History Studies, 11th Grade, Part 2 (2017), p. 54)2. The glorification of terrorists who carried out murderous terrorist attacks is a common phenomenon in the Palestinian Authority and Fatah. -

Awardee: Emily Nasrallah Writer, Lebanon

Awardee: Emily Nasrallah Writer, Lebanon Emily Nasrallah is one of the most well-known writers in the Arab world. In her works written for adults and children, she has found a poetic language to describe everyday life in war-torn Lebanon. In this way, she has contributed over the years to reconciliation between the different populations in Lebanon. Besides war, her main themes are the life of village women and migration. Her first novel, Birds of September (1962), is not only read regularly in Lebanon’s schools today, but is also considered a classic of Arabic literature. Born in 1931, Emily Nasrallah grew up in a Christian family in a village in southern Lebanon. After studying education at the American University in Beirut, she worked as a teacher, then as a journalist and freelance writer. In 1962, her debut novel, Touyour Ayloul (Birds of September), was published and went on to receive three Arabic literary awards. In addition to novels, essays and short stories for adults, Nasrallah has also published seven children’s books. Her writings’ mainly focus on village life in Lebanon, women’s emancipation efforts, identity issues in the Lebanese civil war and migration. Many of her books have been translated into other languages, including English, Spanish, Dutch, Finnish, Thai and German. Although her home and possessions were destroyed in various bomb attacks during the Lebanese civil war, Nasrallah refused to go into exile. Together with a group of female writers, described as the “Beirut Decentrists”, the mother of four remained in Beirut, where she still lives today. -

What Drives Terrorist Innovation? Lessons from Black September And

What Drives Terrorist Innovation? Lessons from Black September and Munich 1972 Authors: Andrew Silke, Cranfield Forensic Institute, Cranfield University, Shrivenham, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Anastasia Filippidou, Centre for International Security and Resilience, Cranfield University, Shrivenham, UK. Abstract: Understanding terrorist innovation has emerged as a critical research question. Terrorist innovation challenges status quo assumptions about the nature of terrorist threats and emphasises a need for counterterrorism policy and practice to attempt to not simply react to changes in terrorist tactics and strategies but also to try to anticipate them. This study focused on a detailed examination of the 1972 Munich Olympics attack and draws on the wide range of open source accounts available, including from terrorists directly involved but also from among the authorities and victims. Using an analytical framework proposed by Rasmussen and Hafez (2010), several key drivers are identified and described, both internal to the group and external to its environment. The study concludes that the innovation shown by Black September was predictable and that Munich represented a profound security failure as much as it did successful terrorist innovation. Keywords: terrorism, terrorist innovation, Munich 1972, Black September 1 Introduction A growing body of research has attempted to identify and understand the factors associated with innovation in terrorism (e.g. Dolnik, 2007; Rasmussen and Hafez, 2010; Horowitz, 2010; Jackson and Loidolt, 2013; Gill, 2017; Rasmussen, 2017). In part this increased attention reflects a concern that more innovative terrorist campaigns might potentially be more successful and/or simply more dangerous. Successful counterterrorist measures and target hardening efforts render previous terrorist tactics ineffective, forcing terrorists to innovate and adapt in order to overcome countermeasures. -

Palestinian Groups

1 Ron’s Web Site • North Shore Flashpoints • http://northshoreflashpoints.blogspot.com/ 2 Palestinian Groups • 1955-Egypt forms Fedayeem • Official detachment of armed infiltrators from Gaza National Guard • “Those who sacrifice themselves” • Recruited ex-Nazis for training • Fatah created in 1958 • Young Palestinians who had fled Gaza when Israel created • Core group came out of the Palestinian Students League at Cairo University that included Yasser Arafat (related to the Grand Mufti) • Ideology was that liberation of Palestine had to preceed Arab unity 3 Palestinian Groups • PLO created in 1964 by Arab League Summit with Ahmad Shuqueri as leader • Founder (George Habash) of Arab National Movement formed in 1960 forms • Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in December of 1967 with Ahmad Jibril • Popular Democratic Front for the Liberation (PDFLP) for the Liberation of Democratic Palestine formed in early 1969 by Nayif Hawatmah 4 Palestinian Groups Fatah PFLP PDFLP Founder Arafat Habash Hawatmah Religion Sunni Christian Christian Philosophy Recovery of Palestine Radicalize Arab regimes Marxist Leninist Supporter All regimes Iraq Syria 5 Palestinian Leaders Ahmad Jibril George Habash Nayif Hawatmah 6 Mohammed Yasser Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf Arafat al-Qudwa • 8/24/1929 - 11/11/2004 • Born in Cairo, Egypt • Father born in Gaza of an Egyptian mother • Mother from Jerusalem • Beaten by father for going into Jewish section of Cairo • Graduated from University of King Faud I (1944-1950) • Fought along side Muslim Brotherhood -

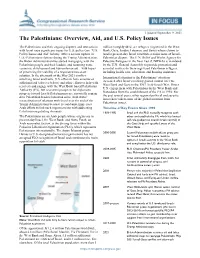

The Palestinians: Overview, 2021 Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues

Updated September 9, 2021 The Palestinians: Overview, Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues The Palestinians and their ongoing disputes and interactions million (roughly 44%) are refugees (registered in the West with Israel raise significant issues for U.S. policy (see “U.S. Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) whose claims to Policy Issues and Aid” below). After a serious rupture in land in present-day Israel constitute a major issue of Israeli- U.S.-Palestinian relations during the Trump Administration, Palestinian dispute. The U.N. Relief and Works Agency for the Biden Administration has started reengaging with the Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is mandated Palestinian people and their leaders, and resuming some by the U.N. General Assembly to provide protection and economic development and humanitarian aid—with hopes essential services to these registered Palestinian refugees, of preserving the viability of a negotiated two-state including health care, education, and housing assistance. solution. In the aftermath of the May 2021 conflict International attention to the Palestinians’ situation involving Israel and Gaza, U.S. officials have announced additional aid (also see below) and other efforts to help with increased after Israel’s military gained control over the West Bank and Gaza in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Direct recovery and engage with the West Bank-based Palestinian U.S. engagement with Palestinians in the West Bank and Authority (PA), but near-term prospects for diplomatic progress toward Israeli-Palestinian peace reportedly remain Gaza dates from the establishment of the PA in 1994. For the past several years, other regional political and security dim. -

The Fatah-Hamas Reconciliation Agreement of October 2017

Introduction Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Comments The Fatah–Hamas Reconciliation Agreement of October 2017 WP S An Opportunity to End Gaza’s Humanitarian Crisis and Permanently Overcome the Blockade Muriel Asseburg Ten years after Hamas violently seized power in Gaza, and following a string of failures to reconcile the Palestinian factions, there are now signs of a rapprochement between Fatah and Hamas. In September 2017 the Hamas leadership announced it would dis- solve the administrative committee it had established in March, opening the way for the Palestinian Authority (PA) to take over the government in the Gaza Strip. In mid- October representatives of Hamas and Fatah signed an Egyptian-mediated reconcilia- tion agreement. On 1 November PA forces were deployed to the Palestinian side of the Rafah border crossing with Egypt. Even if there are still major obstacles to merging the two security apparatuses, establishing a unity government, restoring the democratic process and achieving comprehensive reconciliation – the chances of the rapproche- ment preventing another round of armed conflict and improving the situation for the population in crisis-ridden Gaza are considerably better this time around. Germany and its European partners should help to accentuate the positive dynamics, support permanent improvements of the situation in Gaza through practical steps and work towards comprehensive reconciliation between the Palestinian factions. In practical terms the 12 October 2017 agree- further reconciliation measures are also to ment between the two largest Palestinian be discussed. On 21 November the smaller factions foresees the Palestinian Authority Palestinian factions are invited to put their assuming control of Gaza’s border crossings signatures to the agreement in Cairo, too.