Palestinian Reconciliation and the Potential of Transitional Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaza-Israel: the Legal and the Military View Transcript

Gaza-Israel: The Legal and the Military View Transcript Date: Wednesday, 7 October 2015 - 6:00PM Location: Barnard's Inn Hall 07 October 2015 Gaza-Israel: The Legal and Military View Professor Sir Geoffrey Nice QC General Sir Nick Parker For long enough commentators have usually assumed the Israel - Palestine armed conflict might be lawful, even if individual incidents on both sides attracted condemnation. But is that assumption right? May the conflict lack legality altogether, on one side or both? Have there been war crimes committed by both sides as many suggest? The 2014 Israeli – Gaza conflict (that lasted some 52 days and that was called 'Operation Protective Edge' by the Israeli Defence Force) allows a way to explore some of the underlying issues of the overall conflict. General Sir Nick Parker explains how he advised Geoffrey Nice to approach the conflict's legality and reality from a military point of view. Geoffrey Nice explains what conclusions he then reached. Were war crimes committed by either side? Introduction No human is on this earth as a volunteer; we are all created by an act of force, sometimes of violence just as the universe itself arrived by force. We do not leave the world voluntarily but often by the force of disease. As pressed men on earth we operate according to rules of nature – gravity, energy etc. – and the rules we make for ourselves but focus much attention on what to do when our rules are broken, less on how to save ourselves from ever breaking them. That thought certainly will feature in later lectures on prison and sex in this last year of my lectures as Gresham Professor of Law but is also central to this and the next lecture both on Israel and on parts of its continuing conflict with Gaza. -

Examples of Iraq and Syria

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2017 The Unraveling of the Nation-State in the Middle East: Examples of Iraq and Syria Zachary Kielp Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kielp, Zachary, "The Unraveling of the Nation-State in the Middle East: Examples of Iraq and Syria" (2017). MSU Graduate Theses. 3225. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3225 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNRAVELING OF THE NATION-STATE IN THE MIDDLE EAST: EXAMPLES OF IRAQ AND SYRIA A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Defense and Strategic Studies By Zachary Kielp December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Zachary Kielp ii THE UNRAVELING OF THE NATION-STATE IN THE MIDDLE EAST: EXAMPLES OF IRAQ AND SYRIA Defense and Strategic Studies Missouri State University, December 2017 Master of Science Zachary Kielp ABSTRACT After the carnage of World War One and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire a new form of political organization was brought to the Middle East, the Nation-State. -

10 Ecosy Congress

10 TH ECOSY CONGRESS Bucharest, 31 March – 3 April 2011 th Reports of the 9 Mandate ECOSY – Young European Socialists “Talking about my generation” CONTENTS Petroula Nteledimou ECOSY President p. 3 Janna Besamusca ECOSY Secretary General p. 10 Brando Benifei Vice President p. 50 Christophe Schiltz Vice President p. 55 Kaisa Penny Vice President p. 57 Nils Hindersmann Vice President p. 60 Pedro Delgado Alves Vice President p. 62 Joan Conca Coordinator Migration and Integration network p. 65 Marianne Muona Coordinator YFJ network p. 66 Michael Heiling Coordinator Pool of Trainers p. 68 Miki Dam Larsen Coordinator Queer Network p. 70 Sandra Breiteneder Coordinator Feminist Network p. 71 Thomas Maes Coordinator Students Network p. 72 10 th ECOSY Congress 2 Held thanks to hospitality of TSD Bucharest, Romania 31 st March - 3 rd April 2011 9th Mandate reports ECOSY – Young European Socialists “Talking about my generation” Petroula Nteledimou, ECOSY President Report of activities, 16/04/2009 – 01/04/2011 - 16-19/04/2009 : ECOSY Congress , Brussels (Belgium). - 24/04/2009 : PES Leaders’ Meeting , Toulouse (France). Launch of the PES European Elections Campaign. - 25/04/2009 : SONK European Elections event , Helsinki (Finland). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. - 03/05/2009 : PASOK Youth European Elections event , Drama (Greece). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. - 04/05/2009 : Greek Women’s Union European Elections debate , Kavala (Greece). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. - 07-08/05/2009 : European Youth Forum General Assembly , Brussels (Belgium). - 08/05/2009 : PES Presidency meeting , Brussels (Belgium). - 09-10/05/2009 : JS Portugal European Election debate , Lisbon (Portugal). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. -

Case #2 United States of America (Respondent)

Model International Court of Justice (MICJ) Case #2 United States of America (Respondent) Relocation of the United States Embassy to Jerusalem (Palestine v. United States of America) Arkansas Model United Nations (AMUN) November 20-21, 2020 Teeter 1 Historical Context For years, there has been a consistent struggle between the State of Israel and the State of Palestine led by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). In 2018, United States Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that the U.S. embassy located in Tel Aviv would be moving to the city of Jerusalem.1 Palestine, angered by the embassy moving, filed a case with the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 2018.2 The history of this case, U.S. relations with Israel and Palestine, current events, and why the ICJ should side with the United States will be covered in this research paper. Israel and Palestine have an interesting relationship between war and competition. In 1948, Israel captured the west side of Jerusalem, and the Palestinians captured the east side during the Arab-Israeli War. Israel declared its independence on May 14, 1948. In 1949, the Lausanne Conference took place, and the UN came to the decision for “corpus separatum” which split Jerusalem into a Jewish zone and an Arab zone.3 At this time, the State of Israel decided that Jerusalem was its “eternal capital.”4 “Corpus separatum,” is a Latin term meaning “a city or region which is given a special legal and political status different from its environment, but which falls short of being sovereign, or an independent city-state.”5 1 Office of the President, 82 Recognizing Jerusalem as the Capital of the State of Israel and Relocating the United States Embassy to Israel to Jerusalem § (2017). -

Israel: Background and U.S

Israel: Background and U.S. Relations in Brief Updated September 20, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44245 SUMMARY R44245 Israel: Background and U.S. Relations in Brief September 20, 2019 The following matters are of particular significance to U.S.-Israel relations: Jim Zanotti Israel’s ability to address threats. Israel relies on a number of strengths—including Specialist in Middle regional conventional military superiority—to manage potential threats to its security, Eastern Affairs including evolving asymmetric threats such as rockets and missiles, cross-border tunneling, drones, and cyberattacks. Additionally, Israel has an undeclared but presumed nuclear weapons capability. Against a backdrop of strong bilateral cooperation, Israel’s leaders and supporters routinely make the case that Israel’s security and the broader stability of the region remain critically important for U.S. interests. A 10-year bilateral military aid memorandum of understanding (MOU)— signed in 2016—commits the United States to provide Israel $3.3 billion in Foreign Military Financing annually from FY2019 to FY2028, along with additional amounts from Defense Department accounts for missile defense. All of these amounts remain subject to congressional appropriations. Some Members of Congress criticize various Israeli actions and U.S. policies regarding Israel. In recent months, U.S. officials have expressed some security- related concerns about China-Israel commercial activity. Iran and the region. Israeli officials seek to counter Iranian regional influence and prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons. In April 2018, Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu presented historical information about Iran’s nuclear program that Israeli intelligence apparently seized from an Iranian archive. -

Protest and State–Society Relations in the Middle East and North Africa

SIPRI Policy Paper PROTEST AND STATE– 56 SOCIETY RELATIONS IN October 2020 THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA dylan o’driscoll, amal bourhrous, meray maddah and shivan fazil STOCKHOLM INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE SIPRI is an independent international institute dedicated to research into conflict, armaments, arms control and disarmament. Established in 1966, SIPRI provides data, analysis and recommendations, based on open sources, to policymakers, researchers, media and the interested public. The Governing Board is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. GOVERNING BOARD Ambassador Jan Eliasson, Chair (Sweden) Dr Vladimir Baranovsky (Russia) Espen Barth Eide (Norway) Jean-Marie Guéhenno (France) Dr Radha Kumar (India) Ambassador Ramtane Lamamra (Algeria) Dr Patricia Lewis (Ireland/United Kingdom) Dr Jessica Tuchman Mathews (United States) DIRECTOR Dan Smith (United Kingdom) Signalistgatan 9 SE-169 72 Solna, Sweden Telephone: + 46 8 655 9700 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.sipri.org Protest and State– Society Relations in the Middle East and North Africa SIPRI Policy Paper No. 56 dylan o’driscoll, amal bourhrous, meray maddah and shivan fazil October 2020 © SIPRI 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of SIPRI or as expressly permitted by law. Contents Preface v Acknowledgements vi Summary vii Abbreviations ix 1. Introduction 1 Figure 1.1. Classification of countries in the Middle East and North Africa by 2 protest intensity 2. State–society relations in the Middle East and North Africa 5 Mass protests 5 Sporadic protests 16 Scarce protests 31 Highly suppressed protests 37 Figure 2.1. -

German Hegemony and the Socialist International's Place in Interwar

02_EHQ 31/1 articles 30/11/00 1:53 pm Page 101 William Lee Blackwood German Hegemony and the Socialist International’s Place in Interwar European Diplomacy When the guns fell silent on the western front in November 1918, socialism was about to become a governing force throughout Europe. Just six months later, a Czech socialist could marvel at the convocation of an international socialist conference on post- war reconstruction in a Swiss spa, where, across the lake, stood buildings occupied by now-exiled members of the deposed Habsburg ruling class. In May 1923, as Europe’s socialist parties met in Hamburg, Germany, finally to put an end to the war-induced fracturing within their ranks by launching a new organization, the Labour and Socialist International (LSI), the German Communist Party’s main daily published a pull-out flier for posting on factory walls. Bearing the sarcastic title the International of Ministers, it presented to workers a list of forty-one socialists and the national offices held by them in Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Belgium, Poland, France, Sweden, and Denmark. Commenting on the activities of the LSI, in Paris a Russian Menshevik émigré turned prominent left-wing pundit scoffed at the new International’s executive body, which he sarcastically dubbed ‘the International Socialist Cabinet’, since ‘all of its members were ministers, ex-ministers, or prospec- tive ministers of State’.1 Whether one accepted or rejected its new status, socialism’s virtually overnight transformation from an outsider to a consummate insider at the end of Europe’s first total war provided the most striking measure of the quantum leap into what can aptly be described as Europe’s ‘social democratic moment’.2 Moreover, unlike the period after Europe’s second total war, when many of socialism’s basic postulates became permanently embedded in the post-1945 social-welfare-state con- European History Quarterly Copyright © 2001 SAGE Publications, London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi, Vol. -

Moving-Nowhere.Pdf

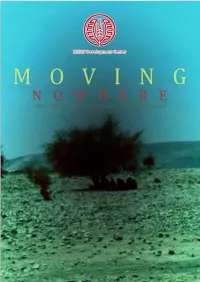

MA’AN Development Center MOVINGMOVING NOWHERE: FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY NOWHERE FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY 1 2 MOVINGMOVING NOWHERE: FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY NOWHERE FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY 2015 3 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Physical Security 6 Eviction Orders And Demolition Orders 10 Psychological Security 18 Livelihood Reductions 22 Environmental Concerns 24 Water 26 Settler Violence 28 Isuues Faced By Other Communities In Area C 32 International Humanitarian Law 36 Conclusion 40 Photo by Hamza Zbiedat Hamza by Photo 4 Moving Nowhere Introduction Indirect and direct forcible transfer is currently at the forefront of Israel’s ideological agenda in area C. Firing zones, initially established as a means of land control, are now being used to create an environment so hostile that Palestinians are forced to leave the area or live in conditions of deteriorating security. re-dating the creation of the state of Israel, there was an ideological agenda within Pcertain political spheres predicated on the notion that Israel should exist from the sea to the Jordan River. Upon creation of the State the subsequent governments sought to establish this notion. This has resulted in an uncompromising programme of colonisation, ethnic cleansing and de-development in Palestine. The conclusion of the six day war in 1967 marked the beginning of the ongoing occupation, under which the full force of the ideological agenda has been extended into the West Bank. Israel has continuously led projects and policies designed to appropriate vast amounts of Palestinian land in the West Bank, despite such actions being illegal under international law. -

“Is the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process Dead?” April 19, 2019 PART

The Brookings Institution Brookings Cafeteria Podcast “Is the Israeli-Palestinian peace process dead?” April 19, 2019 PARTICIPANTS: FRED DEWS Host KHALED ELGINDY Nonresident Fellow - Foreign Policy, Center for Middle East Policy TAMARA COFMAN WITTES Senior Fellow - Foreign Policy, Center for Middle East Policy DAVID WESSEL Senior Fellow, Economic Studies Director, The Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy 1 (MUSIC) DEWS: Welcome to the Brookings Cafeteria, the podcast about ideas and the experts who have them. I'm Fred Dews. On today's episode, an interview with Khaled Elgindy, author of a new book from the Brookings Institution Press, Blind Spot: America and the Palestinians, from Balfour to Trump. Elgindy is a nonresident fellow in the Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings and previously served as an advisor to the Palestinian leadership in Ramallah on permanent status negotiations with Israel from 2004 to 2009 and was a key participant in the Annapolis negotiations throughout 2008. Conducting the interview is Tamara Cofman Wittes. Senior fellow in the Center for Middle East Policy, she served as deputy assistant secretary of state for near eastern affairs from 2009 into 2012. Also, on today's show, Wessel's Economic Update. Today, Senior Fellow David Wessel, offers three reasons why we don't necessarily have to address the rising U.S. budget deficit through increased taxes and cutting spending right now. You can follow the Brookings podcast network on Twitter @policypodcasts to get information about and links to all of our shows, including our new podcast, The Current, which is replacing our 5 on 45 podcast. -

Palestinian Forces

Center for Strategic and International Studies Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy 1800 K Street, N.W. • Suite 400 • Washington, DC 20006 Phone: 1 (202) 775 -3270 • Fax : 1 (202) 457 -8746 Email: [email protected] Palestinian Forces Palestinian Authority and Militant Forces Anthony H. Cordesman Center for Strategic and International Studies [email protected] Rough Working Draft: Revised February 9, 2006 Copyright, Anthony H. Cordesman, all rights reserved. May not be reproduced, referenced, quote d, or excerpted without the written permission of the author. Cordesman: Palestinian Forces 2/9/06 Page 2 ROUGH WORKING DRAFT: REVISED FEBRUARY 9, 2006 ................................ ................................ ............ 1 THE MILITARY FORCES OF PALESTINE ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 2 THE OSLO ACCORDS AND THE NEW ISRAELI -PALESTINIAN WAR ................................ ................................ .............. 3 THE DEATH OF ARAFAT AND THE VICTORY OF HAMAS : REDEFINING PALESTINIAN POLITICS AND THE ARAB - ISRAELI MILITARY BALANCE ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .... 4 THE CHANGING STRUCTURE OF PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY FORC ES ................................ ................................ .......... 5 Palestinian Authority Forces During the Peace Process ................................ ................................ ..................... 6 The -

Israel, Palestine, and the Olso Accords

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 23, Issue 1 1999 Article 4 Israel, Palestine, and the Olso Accords JillAllison Weiner∗ ∗ Copyright c 1999 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Israel, Palestine, and the Olso Accords JillAllison Weiner Abstract This Comment addresses the Middle East peace process, focusing upon the relationship be- tween Israel and Palestine. Part I discusses the background of the land that today comprises the State of Israel and its territories. This Part summarizes the various accords and peace treaties signed by Israel, the Palestinians, and the other surrounding Arab Nations. Part II reviews com- mentary regarding peace in the Middle East by those who believe Israel needs to surrender more land and by those who feel that Palestine already has received too much. Part II examines the conflict over the permanent status negotiations, such as the status of the territories. Part III argues that all the parties need to abide by the conditions and goals set forth in the Oslo Accords before they can realistically begin the permanent status negotiations. Finally, this Comment concludes that in order to achieve peace, both sides will need to compromise, with Israel allowing an inde- pendent Palestinian State and Palestine amending its charter and ending the call for the destruction of Israel, though the circumstances do not bode well for peace in the Middle East. ISRAEL, PALESTINE, AND THE OSLO ACCORDS fillAllison Weiner* INTRODUCTION Israel's' history has always been marked by a juxtaposition between two peoples-the Israelis and the Palestinians 2-each believing that the land is rightfully theirs according to their reli- gion' and history.4 In 1897, Theodore Herzl5 wrote DerJeden- * J.D. -

Using a Civil Suit to Punish/Deter Sponsors of Terrorism: Connecting Arafat & the PLO to the Terror Attacks in the Second In

Digital Commons at St. Mary's University Faculty Articles School of Law Faculty Scholarship 2014 Using a Civil Suit to Punish/Deter Sponsors of Terrorism: Connecting Arafat & the PLO to the Terror Attacks in the Second Intifada Jeffrey F. Addicott St. Mary's University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/facarticles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey F. Addicott, Using a Civil Suit to Punish/Deter Sponsors of Terrorism: Connecting Arafat & the PLO to the Terror Attacks in the Second Intifada, 4 St. John’s J. Int’l & Comp. L. 71 (2014). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USING A CIVIL SUIT TO PUNISH/DETER SPONSORS OF TERRORISM: CONNECTING ARAFAT & THE PLO TO THE TERROR ATTACKS IN THE SECOND INTIFADA Dr. Jeffery Addicott* INTRODUCTION “All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.”1 -Edmund Burke As the so-called “War on Terror” 2 continues, it is imperative that civilized nations employ every possible avenue under the rule of law to punish and deter those governments and States that choose to engage in or provide support to terrorism.3 *∗Professor of Law and Director, Center for Terrorism Law, St. Mary’s University School of Law.