Integrating People Management Into Public Service Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Governor Genera. and the Head of State Functions

The Governor Genera. and the Head of State Functions THOMAS FRANCK* Lincoln, Nebraska In most, though by no means all democratic states,' the "Head o£ State" is a convenient legal and political fiction the purpose of which is to personify the complex political functions of govern- ment. What distinguishes the operations of this fiction in Canada is the fact that the functions of head of state are not discharged by any one person. Some, by legislative enactment, are vested in the Governor General. Others are delegated to the Governor General by the Crown. Still others are exercised by the Queen in person. A survey of these functions will reveal, however, that many more of the duties of the Canadian head of state are to-day dis- charged by the Governor General than are performed by the Queen. Indeed, it will reveal that some of the functions cannot be dis- charged by anyone else. It is essential that we become aware of this development in Canadian constitutional practice and take legal cognizance of the consequently increasing stature and importance of the Queen's representative in Canada. Formal Vesting of Head of State Functions in Constitutional Governments ofthe Commonnealth Reahns In most of the realms of the Commonwealth, the basic constitut- ional documents formally vest executive power in the Queen. Section 9 of the British North America Act, 1867,2 states: "The Executive Government and authority of and over Canada is hereby declared to continue and be vested in the Queen", while section 17 establishes that "There shall be one Parliament for Canada, consist- ing of the Queen, an Upper House, styled the Senate, and the *Thomas Franck, B.A., LL.B. -

Strategic Choices in Reforming Public Service Employment an International Handbook

Strategic Choices in Reforming Public Service Employment An International Handbook Edited by Carlo Dell’Aringa, Guiseppe Della Rocca and Berndt Keller dell'aringa/96590/crc 16/7/01 12:44 pm Page 1 Strategic Choices in Reforming Public Service Employment dell'aringa/96590/crc 16/7/01 12:44 pm Page 2 dell'aringa/96590/crc 16/7/01 12:44 pm Page 3 Strategic Choices in Reforming Public Service Employment An International Handbook Edited by Carlo Dell’Aringa Giuseppe Della Rocca and Berndt Keller dell'aringa/96590/crc 16/7/01 12:44 pm Page 4 Editorial matter and selection © Carlo Dell’Aringa, Giuseppe Della Rocca and Berndt Keller 2001 Chapters 1–9 © Palgrave Publishers Ltd 2001 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2001 by PALGRAVE Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE is the new global academic imprint of St. -

An Orientation Guide for New Or Transferring IOM Staff Members

ME TO THE CO IO EL M W Orientation Guide IN E D M UC AM TION PROGR An orientation guide for new or transferring IOM staff members This Orientation Guide is designed to be a dynamic and informative document that will be updated at regular intervals. This document provides an overview of the policies and procedures applicable at the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and reflects the IOM statutory texts at the time of writing; however, the Guide is not meant to replace the existing body of IOM regulations, rules and instructions. In case of any conflict between this Guide and the regulations, rules and instructions, the latter prevail. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration, advance understanding of migration issues, encourage social and economic development through migration, and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher: International Organization for Migration 17 route des Morillons P.O. Box 17 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 717 91 11 Fax: +41 22 798 61 50 Email: [email protected] Website: www.iom.int © 2018 International Organization for Migration (IOM) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 26_18 WELCOME TO THE IOM Orientation Guide An orientation guide for new or transferring IOM staff members This document presents an overview of the work of the International Organization for Migration (IOM), for new or transferring staff members. -

Action Plan on Bullying – Report of the Anti

Action Plan On Bullying Report of the Anti-Bullying Working Group to the Minister for Education and Skills January 2013 Anti-Bullying Action Plan – Design Template Table of Contents Programme for Government Commitment ................................................................ - 5 - Welcome from Minister ................................................................................................ - 6 - Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... - 8 - Introduction and Background .................................................................................... - 11 - What is bullying? ......................................................................................................... - 15 - Impact of bullying ...................................................................................................... - 31 - What do children and young people say about bullying? .................................... - 45 - What are schools already required to do? .............................................................. - 51 - Do we need more legislation? .................................................................................. - 69 - Responses to bullying in schools............................................................................... - 75 - This is not a problem schools can solve alone ........................................................ - 93 - Action Plan on Bullying ........................................................................................... -

Counter-Bullying Policy

COUNTER-BULLYING POLICY CONTENTS OVERVIEW 1 AIMS 1 LAW AND GUIDANCE 2 CRIMINAL LAW 2 WHAT IS BULLYING? 2 CYBER-BULLYING 3 PREVENTION 3 INVOLVEMENT OF PARENTS 3 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 3 INVOLVEMENT OF PUPILS 4 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 4 REGULAR EVALUATION AND UPDATING 5 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 5 IMPLEMENTATION OF DISCIPLINARY SANCTIONS 5 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 5 OPEN DISCUSSION OF DIFFERENCES 5 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 5 CHARITABLE WORK – ENHANCEMENT OF CHARACTER 6 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 6 PROVISION OF EFFECTIVE STAFF TRAINING 6 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 6 LIAISON WITH LOCAL EXTERNAL AGENCIES 6 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 6 CLEAR AND EASY LINES OF COMMUNICATION FOR BOYS 6 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 7 CREATION OF AN INCLUSIVE ENVIRONMENT 7 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 7 PROCEDURES FOR HANDLING BULLYING 7 WHERE BULLYING HAS SEVERE IMPACT 7 INTERVENTION – DISCIPLINE AND TACKLING UNDERLYING ISSUES OF BULLYING 8 DISCIPLINE AND SANCTIONS 8 TACKLING UNDERLYING ISSUES 8 APPENDIX A: PROCEDURES FOR DEALING WITH BULLYING TYPE BEHAVIOUR 9 APPENDIX B: COUNTER-BULLYING GUIDANCE FOR BOYS 1 OVERVIEW The School recognises that it has a duty of care to maintain a working environment for its staff and a learning environment for its pupils in which honesty, integrity and respect are reflected in personal behaviour and standards of conduct, where the welfare of pupils is paramount and where the working environment is safe. In turn, members of staff must recognise that that they are each accountable for their actions. They have a duty not only to keep young people safe but also to protect them from physical and emotional harm. -

General Practice Nursing Induction Template

General Practice Nursing Induction Template 1 CONTENTS Background 3 Introduction 3 Aims and Objectives 4 Glossary of Terms 4 General Practice Nursing 5 Orientation 32 Employers 34 Education 41 Resources 49 Acknowledgements 49 External Review Panel 50 References 51 2 Background The General Practice Nursing 10 Point Plan (GPN10PP) (https://www.england.nhs.uk/ leadingchange/staff-leadership/general-practice-nursing/) has given an investment of £15 million from the General Practice Forward View (GPFV) funding allocation, to support action which will address the significant workforce challenges and support improvements in General Practice nursing (GPN) by 2020. The plan was initially led by Professor Jane Cummings, Chief Nursing Officer for England and its overarching focus is to build and develop the capacity and capability that is needed across the whole primary care workforce, as well as building GPN capability to support improved and innovative approaches in delivering health and wellbeing. The basis of this work has now been taken up by the new CNO, Dr Ruth May, who maintains that: “Nursing staff will be at the heart of all plans to provide care fit for the 21st century and the nurse leadership voice is crucial to the broad health and care policy debate.” Nursing in Practice (2019) Within General Practice, it has been identified that there are significant variations between different practices in relation to orientation and induction of GPNs into this new work environment. Some nurses are offered structured courses that develop and steer them into the role gradually, while others are given as little as a week’s induction before being expected to work alone. -

Probationary Policy

PROBATIONARY POLICY RATIFIED BY THE TRUST BOARD IN: APRIL 2020 NEXT REVIEW DATE: APRIL 2020 April 2020 1 PROBATIONARY POLICY Person responsible for this policy: Angela Ransby Policy author: Angela Ransby Date to Trust Board: April 2020 Date Ratified: April 2020 Date to be Reviewed: April 2021 Policy displayed on website: Yes CEO Signature: A Ransby Trust Board Signature: R Fern Updates made: Date: Appendix 1 – updated induction programme 23 October 2020 added P3 – extension period amended to 9 months in 28 June 2021 line with contracts Introduction It is the Raedwald Trust’s policy to operate probationary periods for all new employees, and in some cases, at the Trust’s discretion, in respect of employees who have been transferred or promoted into different posts within the school. This policy allows both the employee and Raedwald Trust to assess objectively whether or not the employee is suitable for the role. The Raedwald Trust believes that the use of probationary periods increases the likelihood that new employees will perform effectively in their employment. April 2020 2 The Head Teacher is responsible for ensuring that all new employees are properly monitored during their probationary period. If any problems arise, the Head Teacher should address these promptly and in accordance with the policy. The employee should be made aware that some aspects of their performance or conduct is unsatisfactory. This will help prevent the problem from escalating and hopefully lead to sufficient improvements. Where the employee is the Head Teacher, the CEO shall be responsible for managing the probation process and determining whether their employment is confirmed or their employment is terminated. -

THE DECLINE of MINISTERIAL ACCOUNTABILITY in CANADA by M. KATHLEEN Mcleod Integrated Studies Project Submitted to Dr.Gloria

THE DECLINE OF MINISTERIAL ACCOUNTABILITY IN CANADA By M. KATHLEEN McLEOD Integrated Studies Project submitted to Dr.Gloria Filax in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Integrated Studies Athabasca, Alberta Submitted April 17, 2011 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................. ii Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 The Westminster System of Democratic Government ................................................................... 3 Ministerial Accountability: All the Time, or Only When it is Convenient? ................................... 9 The Richard Colvin Case .................................................................................................................. 18 The Over-Arching Power of the Prime Minister ............................................................................ 24 Michel Foucault and Governmentality ............................................................................................ 31 Governmentality .......................................................................................................................... 31 Governmentality and Stephen Harper ............................................................................................ 34 Munir Sheikh and the Long Form Census ....................................................................................... -

Actuarial Report on the Pension Plan for the Public Service of Canada (PSPP) Was Made Pursuant to the Public Pensions Reporting Act (PPRA)

ACTUARIAL REPORT on the Pension Plan for the PUBLIC SERVICE OF CANADA as at 31 March 2017 Office of the Chief Actuary Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada 12th Floor, Kent Square Building 255 Albert Street Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0H2 Facsimile: 613-990-9900 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2018 Cat. No. IN3-16/10E-PDF ISSN 1701-8269 ACTUARIAL REPORT Pension Plan for the PUBLIC SERVICE OF CANADA as at 31 March 2017 7 September 2018 The Honourable Scott Brison, P.C., M.P. President of the Treasury Board Ottawa, Canada K1A 0R5 Dear Minister: Pursuant to Section 6 of the Public Pensions Reporting Act, I am pleased to submit the report on the actuarial review as at 31 March 2017 of the pension plan for the Public Service of Canada. This actuarial review is in respect of pension benefits and contributions which are defined by Parts I, III and IV of the Public Service Superannuation Act, the Special Retirement Arrangements Act and the Pension Benefits Division Act. Yours sincerely, Jean-Claude Ménard, F.S.A., F.C.I.A. Chief Actuary Office of the Chief Actuary ACTUARIAL REPORT Pension Plan for the PUBLIC SERVICE OF CANADA as at 31 March 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 7 A. Purpose of Actuarial Report ............................................................................................. 7 B. Valuation Basis ............................................................................................................... -

Members' Allowances and Services Manual

MEMBERS’ ALLOWANCES AND SERVICES Table of Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1-1 2. Governance and Principles ....................................................................................... 2-1 1. Introduction ................................................................................................. 2-2 2. Governing Principles .................................................................................... 2-2 3. Governance Structure .................................................................................. 2-6 4. House Administration .................................................................................. 2-7 3. Members’ Salary and Benefits .................................................................................. 3-1 1. Introduction ................................................................................................. 3-2 2. Members’ Salary .......................................................................................... 3-2 3. Insurance Plans ............................................................................................ 3-3 4. Pension ........................................................................................................ 3-5 5. Relocation .................................................................................................... 3-6 6. Employee and Family Assistance Program .................................................. 3-8 7. -

An Analysis of the Influence of Induction Programmes on Beginner Teachers’ Professional Development in the Erongo Region of Namibia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository An analysis of the influence of induction programmes on beginner teachers’ professional development in the Erongo Region of Namibia by Twahafifwa Ndahekelekwa Tupavali Nghaamwa Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Masters in Public Administration in the faculty of Management Science at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Zwelinzima Ndevu March 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (safe to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This empirical study is based on the need to analyse how induction programmes influence the personal growth and professional development of beginner teachers in the Erongo Region, Namibia. This perceived need prompted the interest to carry out an empirical study to ascertain how induction programmes in the Erongo Region influenced the personal and professional growth of novice teachers. In order to augment the study, the following research objectives were formulated with an aim to determine the extent to which induction programmes influence the beginner teachers’ personal growth and professional development. In operationalising the study, the qualitative research methodology in which a phenomenological research design was used, was utilized to come up with the intended outcomes. -

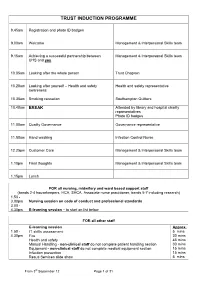

Trust Induction Programme

TRUST INDUCTION PROGRAMME 8.45am Registration and photo ID badges 9.00am Welcome Management & Interpersonal Skills team 9.15am Achieving a successful partnership between Management & Interpersonal Skills team UHS and you 10.05am Looking after the whole person Trust Chaplain 10.20am Looking after yourself – Health and safety Health and safety representative awareness 10.35am Smoking cessation Southampton Quitters 10.40am BREAK Attended by library and hospital charity representatives Photo ID badges 11.00am Quality Governance Governance representative 11.50am Hand washing Infection Control Nurse 12.25pm Customer Care Management & Interpersonal Skills team 1.10pm Final thoughts Management & Interpersonal Skills team 1.15pm Lunch FOR all nursing, midwifery and ward based support staff (bands 2-4 housekeepers, HCA, SHCA, Associate nurse practitioner, bands 5-7 including research) 1.50 - 3.00pm Nursing session on code of conduct and professional standards 3.00 - 4.30pm E-learning session – to start on list below FOR all other staff E-learning session Approx. 1.50 - IT skills assessment 5 mins 4.30pm Fire 30 mins Health and safety 45 mins Manual Handling - non-clinical staff do not complete patient handling section 30 mins Equipment - non-clinical staff do not complete medical equipment section 15 mins Infection prevention 15 mins Resus Services slide show 5 mins From 3rd September 12 Page 1 of 31 CCoonntteennttss ppaaggee From 3rd September 12 Page 2 of 31 Welcome to University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust This folder aims to help you in the initial period of your employment with UHS by providing a checklist of information that is paced over your first three months.