Performance-Related Pay and the Teaching Profession: a Review of the Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Orientation Guide for New Or Transferring IOM Staff Members

ME TO THE CO IO EL M W Orientation Guide IN E D M UC AM TION PROGR An orientation guide for new or transferring IOM staff members This Orientation Guide is designed to be a dynamic and informative document that will be updated at regular intervals. This document provides an overview of the policies and procedures applicable at the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and reflects the IOM statutory texts at the time of writing; however, the Guide is not meant to replace the existing body of IOM regulations, rules and instructions. In case of any conflict between this Guide and the regulations, rules and instructions, the latter prevail. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration, advance understanding of migration issues, encourage social and economic development through migration, and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher: International Organization for Migration 17 route des Morillons P.O. Box 17 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 717 91 11 Fax: +41 22 798 61 50 Email: [email protected] Website: www.iom.int © 2018 International Organization for Migration (IOM) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 26_18 WELCOME TO THE IOM Orientation Guide An orientation guide for new or transferring IOM staff members This document presents an overview of the work of the International Organization for Migration (IOM), for new or transferring staff members. -

Action Plan on Bullying – Report of the Anti

Action Plan On Bullying Report of the Anti-Bullying Working Group to the Minister for Education and Skills January 2013 Anti-Bullying Action Plan – Design Template Table of Contents Programme for Government Commitment ................................................................ - 5 - Welcome from Minister ................................................................................................ - 6 - Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... - 8 - Introduction and Background .................................................................................... - 11 - What is bullying? ......................................................................................................... - 15 - Impact of bullying ...................................................................................................... - 31 - What do children and young people say about bullying? .................................... - 45 - What are schools already required to do? .............................................................. - 51 - Do we need more legislation? .................................................................................. - 69 - Responses to bullying in schools............................................................................... - 75 - This is not a problem schools can solve alone ........................................................ - 93 - Action Plan on Bullying ........................................................................................... -

Counter-Bullying Policy

COUNTER-BULLYING POLICY CONTENTS OVERVIEW 1 AIMS 1 LAW AND GUIDANCE 2 CRIMINAL LAW 2 WHAT IS BULLYING? 2 CYBER-BULLYING 3 PREVENTION 3 INVOLVEMENT OF PARENTS 3 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 3 INVOLVEMENT OF PUPILS 4 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 4 REGULAR EVALUATION AND UPDATING 5 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 5 IMPLEMENTATION OF DISCIPLINARY SANCTIONS 5 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 5 OPEN DISCUSSION OF DIFFERENCES 5 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 5 CHARITABLE WORK – ENHANCEMENT OF CHARACTER 6 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 6 PROVISION OF EFFECTIVE STAFF TRAINING 6 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 6 LIAISON WITH LOCAL EXTERNAL AGENCIES 6 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 6 CLEAR AND EASY LINES OF COMMUNICATION FOR BOYS 6 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 7 CREATION OF AN INCLUSIVE ENVIRONMENT 7 WHAT DOES THE SCHOOL DO? 7 PROCEDURES FOR HANDLING BULLYING 7 WHERE BULLYING HAS SEVERE IMPACT 7 INTERVENTION – DISCIPLINE AND TACKLING UNDERLYING ISSUES OF BULLYING 8 DISCIPLINE AND SANCTIONS 8 TACKLING UNDERLYING ISSUES 8 APPENDIX A: PROCEDURES FOR DEALING WITH BULLYING TYPE BEHAVIOUR 9 APPENDIX B: COUNTER-BULLYING GUIDANCE FOR BOYS 1 OVERVIEW The School recognises that it has a duty of care to maintain a working environment for its staff and a learning environment for its pupils in which honesty, integrity and respect are reflected in personal behaviour and standards of conduct, where the welfare of pupils is paramount and where the working environment is safe. In turn, members of staff must recognise that that they are each accountable for their actions. They have a duty not only to keep young people safe but also to protect them from physical and emotional harm. -

General Practice Nursing Induction Template

General Practice Nursing Induction Template 1 CONTENTS Background 3 Introduction 3 Aims and Objectives 4 Glossary of Terms 4 General Practice Nursing 5 Orientation 32 Employers 34 Education 41 Resources 49 Acknowledgements 49 External Review Panel 50 References 51 2 Background The General Practice Nursing 10 Point Plan (GPN10PP) (https://www.england.nhs.uk/ leadingchange/staff-leadership/general-practice-nursing/) has given an investment of £15 million from the General Practice Forward View (GPFV) funding allocation, to support action which will address the significant workforce challenges and support improvements in General Practice nursing (GPN) by 2020. The plan was initially led by Professor Jane Cummings, Chief Nursing Officer for England and its overarching focus is to build and develop the capacity and capability that is needed across the whole primary care workforce, as well as building GPN capability to support improved and innovative approaches in delivering health and wellbeing. The basis of this work has now been taken up by the new CNO, Dr Ruth May, who maintains that: “Nursing staff will be at the heart of all plans to provide care fit for the 21st century and the nurse leadership voice is crucial to the broad health and care policy debate.” Nursing in Practice (2019) Within General Practice, it has been identified that there are significant variations between different practices in relation to orientation and induction of GPNs into this new work environment. Some nurses are offered structured courses that develop and steer them into the role gradually, while others are given as little as a week’s induction before being expected to work alone. -

Probationary Policy

PROBATIONARY POLICY RATIFIED BY THE TRUST BOARD IN: APRIL 2020 NEXT REVIEW DATE: APRIL 2020 April 2020 1 PROBATIONARY POLICY Person responsible for this policy: Angela Ransby Policy author: Angela Ransby Date to Trust Board: April 2020 Date Ratified: April 2020 Date to be Reviewed: April 2021 Policy displayed on website: Yes CEO Signature: A Ransby Trust Board Signature: R Fern Updates made: Date: Appendix 1 – updated induction programme 23 October 2020 added P3 – extension period amended to 9 months in 28 June 2021 line with contracts Introduction It is the Raedwald Trust’s policy to operate probationary periods for all new employees, and in some cases, at the Trust’s discretion, in respect of employees who have been transferred or promoted into different posts within the school. This policy allows both the employee and Raedwald Trust to assess objectively whether or not the employee is suitable for the role. The Raedwald Trust believes that the use of probationary periods increases the likelihood that new employees will perform effectively in their employment. April 2020 2 The Head Teacher is responsible for ensuring that all new employees are properly monitored during their probationary period. If any problems arise, the Head Teacher should address these promptly and in accordance with the policy. The employee should be made aware that some aspects of their performance or conduct is unsatisfactory. This will help prevent the problem from escalating and hopefully lead to sufficient improvements. Where the employee is the Head Teacher, the CEO shall be responsible for managing the probation process and determining whether their employment is confirmed or their employment is terminated. -

An Analysis of the Influence of Induction Programmes on Beginner Teachers’ Professional Development in the Erongo Region of Namibia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository An analysis of the influence of induction programmes on beginner teachers’ professional development in the Erongo Region of Namibia by Twahafifwa Ndahekelekwa Tupavali Nghaamwa Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Masters in Public Administration in the faculty of Management Science at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Zwelinzima Ndevu March 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (safe to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This empirical study is based on the need to analyse how induction programmes influence the personal growth and professional development of beginner teachers in the Erongo Region, Namibia. This perceived need prompted the interest to carry out an empirical study to ascertain how induction programmes in the Erongo Region influenced the personal and professional growth of novice teachers. In order to augment the study, the following research objectives were formulated with an aim to determine the extent to which induction programmes influence the beginner teachers’ personal growth and professional development. In operationalising the study, the qualitative research methodology in which a phenomenological research design was used, was utilized to come up with the intended outcomes. -

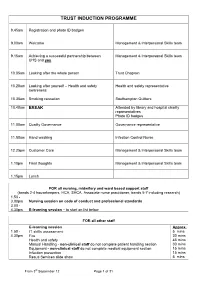

Trust Induction Programme

TRUST INDUCTION PROGRAMME 8.45am Registration and photo ID badges 9.00am Welcome Management & Interpersonal Skills team 9.15am Achieving a successful partnership between Management & Interpersonal Skills team UHS and you 10.05am Looking after the whole person Trust Chaplain 10.20am Looking after yourself – Health and safety Health and safety representative awareness 10.35am Smoking cessation Southampton Quitters 10.40am BREAK Attended by library and hospital charity representatives Photo ID badges 11.00am Quality Governance Governance representative 11.50am Hand washing Infection Control Nurse 12.25pm Customer Care Management & Interpersonal Skills team 1.10pm Final thoughts Management & Interpersonal Skills team 1.15pm Lunch FOR all nursing, midwifery and ward based support staff (bands 2-4 housekeepers, HCA, SHCA, Associate nurse practitioner, bands 5-7 including research) 1.50 - 3.00pm Nursing session on code of conduct and professional standards 3.00 - 4.30pm E-learning session – to start on list below FOR all other staff E-learning session Approx. 1.50 - IT skills assessment 5 mins 4.30pm Fire 30 mins Health and safety 45 mins Manual Handling - non-clinical staff do not complete patient handling section 30 mins Equipment - non-clinical staff do not complete medical equipment section 15 mins Infection prevention 15 mins Resus Services slide show 5 mins From 3rd September 12 Page 1 of 31 CCoonntteennttss ppaaggee From 3rd September 12 Page 2 of 31 Welcome to University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust This folder aims to help you in the initial period of your employment with UHS by providing a checklist of information that is paced over your first three months. -

Induction Programme Settling in Your New Starter

Induction Programme Settling in your new starter Frankly; it’s not just about recruitment. Fantastic, we have found you the perfect candidate for your role. Our job doesn’t end there. We want to support you and your new member of staff during the “settling in period”. Do you have a plan? Starting a new job and joining an established team can be terrifying and the fear of looking stupid debilitating. If the feeling of unease is strong enough you may lose the candidate you worked so hard to find. It is therefore worth spending the time on an effective induction. A well planned, well managed induction will avoid accidents and will increase the speed of full productivity as well as avoid costs incurred in unnecessary recruitment to replace the lost employee. The First Contact Usually the first contact will be with HR or a Line Manager. This person should aim to give a clear picture of the working of the business. • A warm welcome to the company – don’t leave your new starter hanging around waiting for you! • Pay – Address method of payment, holiday entitlements, hours of work and any benefits. • Take payroll information • Provide a staff handbook if available or make clear information on absence reporting, policy and procedures • Do they smoke? Communicate smoking areas and policies • Confirm induction process • Ensure the employee has opportunity to ask questions . Induction Checklist – HR/Line Manager 1. Management Structure Information 2. Take copies of ID, qualifications 3. Take emergency contact details 4. Give salary details 5. Method of salary payment 6. -

One Team: a Historical Analysis of Inequalities Between Men's and Women's Professional Soccer Allyson O

College of the Holy Cross CrossWorks Gender, Sexuality and Women's Studies Student Gender, Sexuality and Women's Studies Scholarship 5-9-2018 One Team: A Historical Analysis of Inequalities between Men's and Women's Professional Soccer Allyson O. Braciska College of the Holy Cross, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/gsw_stu_scholarship Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Income Distribution Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Braciska, Allyson O., "One Team: A Historical Analysis of Inequalities between Men's and Women's Professional Soccer" (2018). Gender, Sexuality and Women's Studies Student Scholarship. 13. https://crossworks.holycross.edu/gsw_stu_scholarship/13 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Gender, Sexuality and Women's Studies at CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gender, Sexuality and Women's Studies Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of CrossWorks. One Nation, One Team: A Historical Analysis of Inequalities between Men's and Women's Professional Soccer Allyson Braciska GSWS Capstone Professor Anne Blaschke 5/9/2017 One Nation, One Team: A Historical Analysis of Inequalities Between Men's and Women's Professional Soccer Braciska Background: The sport of soccer is one of the oldest and most popular organized athletic activities in the world. When comparing participation rates, revenue figures, and overall popularity, there is no doubt that soccer deserves the title of “the world’s sport.” It has been utilized to bring many nations together by rallying for a common cause, fostering incorporation and participation, and providing a source of entertainment to millions. -

Induction Programme Guidance for Managers of Social Care Workers How to Support Your Staff Introduction

Induction Programme Guidance for Managers of Social Care Workers How to Support Your Staff Introduction The Northern Ireland Social Care Council The Social Care Council Induction (Social Care Council) was established in Programme identifies the fundamental 2001 as the regulatory body for the social knowledge required by new workers to allow care workforce in Northern Ireland. them to do their job safely and effectively. The Social Care Council regulates the workforce by As a manager, you are responsible for supporting new maintaining a register and setting standards for the workers in their training and development to help them conduct, practice and training of social care workers to advance the skills and knowledge they will need in order ensure that the quality of care provided to service users to practise competently. and carers is of a high standard. This guide provides sample questions and managers’ Our register is a public record which indicates that those notes to help you use the Social Care Council Induction registered have met the requirements for entry onto the Programme effectively with your employees. The register and have agreed to follow the Social Care programme’s aim is to ensure that workers provide high Council Standards of Conduct and Practice. quality care and support, offering them the first step in continuing professional career development. Standards for Employers of Social Workers and Social Care Workers Social Care employers must meet the standards set out in the Social Care Council Standards for Employers of Social Workers and Social Care Workers (2017). The standards require employers to establish a competent workforce and to support employees to develop their skills and knowledge. -

Sample Induction Policy and Checklist INDUCTION

INDUCTION The aim of an induction program to enable staff to be introduced into a new post and working environment quickly, so that they can contribute effectively as soon as possible. The induction policy, associated procedures and guidelines aim to set out general steps for managers and staff to follow during the induction process. It is expected that all managers and staff will adhere to this policy. The Company expects that the implementation of good induction practice by managers/supervisors will: • Enable new employees to settle into the Company quickly and become productive and efficient members of staff within a short period of time. • Ensure that new entrants are highly motivated and that this motivation is reinforced. • Assist in reducing staff turnover, lateness, absenteeism and poor performance generally. Assist in developing a management style where the emphasis is on leadership. • Ensure that employees operate in a safe working environment. • Will reduce costs associated with repeated recruitment, training and lost production. Sample Induction Policy and Checklist POLICY STATEMENT 1. GENERAL <Company> believes that all new employees MUST be given timely induction training. This training is regarded as a vital part of staff recruitment and integration into the working environment. This policy, associated procedures and guidelines define the Company’s commitment to ensure that all staff are supported during the period of induction, to the benefit of the employee and Company alike. 2. AIM It is the aim of the Company to ensure that staff induction is dealt with in an organised and consistent manner, to enable staff to be introduced into a new post and working environment quickly, so that they can contribute effectively as soon as possible. -

Safeguarding 2

ANTI-BULLYING POLICY SAFEGUARDING 2: ANTI-BULLYING POLICY Issued by: Assistant Directors of Boarding Last review: January 2020 Next review due: January 2021 Most recent edit: September 2020 Circulation: Governing Council Staff Website Parents Students KMD 1 ANTI-BULLYING POLICY Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Definition of Bullying .................................................................................................................................. 3 Types of Bullying ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Severe Bullying ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Vulnerability to Bullying ............................................................................................................................ 4 Symptoms of Bullying .............................................................................................................................. 4 Procedures for Responding to Bullying ................................................................................................... 5 Sanctions ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Cyberbullying .............................................................................................................................................