Interactive Documentary: Setting the Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intra-Actions with Educational Media at the National Film Board of Canada, 1960-2016

Making Waves: Intra-actions with Educational Media at the National Film Board of Canada, 1960-2016 CAROLYN STEELE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PRODRAM IN COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE APRIL 2017 YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO © Carolyn Steele 2017 ABSTRACT This dissertation aims to excavate the narrative of educational programming at the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) from 1960 to 2016. The producers and creative staff of Studio G – the epicentre of educational programming at the NFB for over thirty years – produced extraordinarily diverse and innovative multimedia for the classroom. ‘Multimedia’ is here understood as any media form that was not film, including filmstrips, slides, overhead projecturals, laserdiscs and CDs. To date, there have been no attempts to document the history of educational programming at the NFB generally, nor to situate the history of Studio G within that tradition. Over the course of five years, I have interviewed thirty-four NFB technicians, administrators, producers and directors in the service of creating a unique collective narrative tracing the development of educational media and programming at the NFB over the past fifty- six years and began to piece together an archive of work that has largely been forgotten. Throughout this dissertation, I argue that the forms of media engagement pioneered by Studio G and its descendants fostered a desire for, and eventually an expectation for specific media affordances, namely the ability to sequence or navigate media content, to pace one’s progress through media, to access media on demand and to modify media content. -

May 6–15, 2011 Festival Guide Vancouver Canada

DOCUMENTARY FILM FESTIVAL MAY 6–15, 2011 FESTIVAL GUIDE VANCOUVER CANADA www.doxafestival.ca facebook.com/DOXAfestival @doxafestival PRESENTING PARTNER ORDER TICKETS TODAY [PAGE 5] GET SERIOUSLY CREATIVE Considering a career in Art, Design or Media? At Emily Carr, our degree programs (BFA, BDes, MAA) merge critical theory with studio practice and link you to industry. You’ll gain the knowledge, tools and hands-on experience you need for a dynamic career in the creative sector. Already have a degree, looking to develop your skills or just want to experiment? Join us this summer for short courses and workshops for the public in visual art, design, media and professional development. Between May and August, Continuing Studies will off er over 180 skills-based courses, inspiring exhibits and special events for artists and designers at all levels. Registration opens March 31. SUMMER DESIGN INSTITUTE | June 18-25 SUMMER INSTITUTE FOR TEENS | July 4-29 Table of Contents Tickets and General Festival Info . 5 Special Programs . .15 The Documentary Media Society . 7 Festival Schedule . .42 Acknowledgements . 8 Don’t just stand there — get on the bus! Greetings from our Funders . .10 Essay by John Vaillant . 68. Welcome from DOXA . 11 NO! A Film of Sexual Politics — and Art Essay by Robin Morgan . 78 Awards . 13 Youth Programs . 14 SCREENINGS OPEning NigHT: Louder Than a Bomb . .17 Maria and I . 63. Closing NigHT: Cave of Forgotten Dreams . .21 The Market . .59 A Good Man . 33. My Perestroika . 73 Ahead of Time . 65. The National Parks Project . 31 Amnesty! When They Are All Free . -

NFB TEAM Producer Mixing Hugues Sweeney Serge Boivin Geoffrey Mitchell Administrator Jean-Paul Vialard Manon Provencher Luc Léger

nfb.ca/mytribe An interActive documentAry thAt Allows us to experience the worlds of 8 music fAns And see how the internet trAnsforms their interpersonAl relAtionships And helps forge their identity. 8 chArActers, 8 music styles, 8 views of the web And sociAl networks. PRESS KIT An interActive documentAry thAt Allows us to experience the worlds of 8 music fAns And see how the internet trAnsforms their interpersonAl relAtionships And helps forge their identity. 8 chArActers, 8 music styles, 8 views of the web And sociAl networks. nfb.ca/mytribe from reallife? is it a powerful conversely, engine for the distinctions construction or, of new communities? Can the virtual even be dissociated apprehend the world’s diversity if they are systematically searching for what is But “the can same?” Does the the reassurance Internet offered erase cultural by this virtual social life result in isolation, even to the exclusion of reality? “safe virtual home”,aspaceinwhichtoopenupandrevealone’strueself. How do users a becomes thus Web The validated. been has identity their that proof opinions—all and approval, of signs comments, receive to for their “fellows,” they choose a tribe to which to belong. In return for expressing themselves, sharing and posting, they expect Online social networks enable people to images share and music, emotions. information, Looking vehicle for forging an identity. each To his own “tribe”: Goth, emo, reggae, rap, vampire … Music is often more than a simple cultural product; it acts as a born between1982and1996.Thispermanentconnectionnecessarilychangeshowtheyseetheworld. users “connected”)—Web (for “C” Generation is This online. week a hours twenty than more spending are Quebecers young went, goes virtual, the definition remains unchanged but the practice revolutionizesTwenty everyday years after life. -

2012–2013 NFB Annual Report

Annual Report T R L REPO A NNU 20 1 2 A 201 3 TABLE 03 Governance OF CONTENTS 04 Management 01 Message from 05 Summary of the NFB Activities 02 Awards Received 06 Financial Statements Annex I NFB Across Canada Annex II Productions Annex III Independent Film Projects Supported by ACIC and FAP Photos from French Program productions are featured in the French-language version of this annual report at http://onf-nfb.gc.ca/rapports-annuels. © 2013 National Film Board of Canada ©Published 2013 National by: Film Board of Canada Corporate Communications PublishedP.O. Box 6100,by: Station Centre-ville CorporateMontreal, CommunicationsQuebec H3C 3H5 P.O. Box 6100, Station Centre-ville Montreal,Phone:© 2012 514-283-2469 NationalQuebec H3CFilm Board3H5 of Canada Fax: 514-496-4372 Phone:Internet:Published 514-283-2469 onf-nfb.gc.ca by: Fax:Corporate 514-496-4372 Communications Internet:ISBN:P.O. Box 0-7722-1272-4 onf-nfb.gc.ca 6100, Station Centre-ville Montreal, Quebec H3C 3H5 4th quarter 2013 ISBN: 0-7722-1272-4 4thPhone: quarter 514-283-2469 2013 GraphicFax: 514-496-4372 design: Oblik Communication-design GraphicInternet: design: ONF-NFB.gc.ca Oblik Communication-design ISBN: 0-7722-1271-6 4th quarter 2012 Cover: Stories We Tell, Sarah Polley Graphic design: Folio et Garetti Cover: Stories We Tell, Sarah Polley Cover: Soldier Brother Printed in Canada/100% recycled paper Printed in Canada/100% recycled paper Printed in Canada/100% recycled paper 2012–2013 NFB Annual Report 2012–2013 93 Independent film projects IN NUMBERS supported by the NFB (FAP and ACIC) 76 Original NFB films and 135 co-productions Awards 8 491 New productions on Interactive websites NFB.ca/ONF.ca 83 33,721 Digital documents supporting DVD units (and other products) interactive works sold in Canada * 7,957 2 Public installations Public and private screenings at the NFB mediatheques (Montreal and Toronto) and other community screenings 3 Applications for tablets 6,126 Television broadcasts in Canada * The NFB mediatheques were closed on September 1, 2012, and the public screening program was expanded. -

Interactive Project Proposals: the Early Stages

Working With the NFB’s Digital Studio June 2015 Working With the NFB’s Digital Studio As a unique creative and cultural laboratory, The NFB is eager to explore what it means to “create” and “connect” with Canadians in the age of technology. We are looking to work with a wide range of Canadian artists and media-makers interested in experimenting with the creative application of platforms and technology to story and form. Filmmakers, Interactive Designers, Photographers, Social Media Producers, Graphic Artists, Information Architects, Writers, Video and Sound Artists, Musicians, etc. We are excited by the collaborative nature of media today and are open to receiving project proposals from all types of artists and creators. What Kinds of Creations? As a public producer we have a duty to contribute to the ongoing social discourse of the day through the production of creative audiovisual works. We remain convinced of the powerful and transformative effects of art and imagination for the public good. We have a strong code of ethics that guides our work including the importance of an artistic voice and a diversity of voices, authenticity and creative excellence, innovation and risk taking, social relevance and the promotion of a civic, inclusive democratic culture. Our approach to story is innovative, open-ended, and participatory. We strive to create groundbreaking works that harness the appropriate technologies for each story and/or audience group, and contain built-in channels that open the project up for direct engagement. We are currently looking to produce new works that help us achieve our mission including interactive documentaries, mobile and locative media, interactive animations, photographic art and essays, data visualizations, physical installations, community media, interactive video, user- generated media, etc. -

No Classes, University Open) Oct

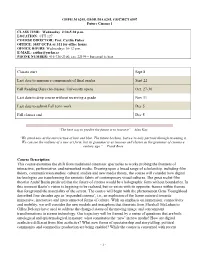

GS/FILM 6245, GS/HUMA 6245, GS/CMCT 6507 Future Cinema 1 CLASS TIME: Wednesday 2:30-5:30 p.m. LOCATION: CFT 127 COURSE DIRECTOR: Prof. Caitlin Fisher OFFICE: 303F GCFA or 311 for office hours OFFICE HOURS: Wednesdays 10-12 p.m. E-MAIL: [email protected] PHONE NUMBER: 416-736-2100, ext. 22199 – but email is best Classes start Sept 8 Last date to announce components of final grades Sept 22 Fall Reading Days (no classes, University open) Oct. 27-30 Last date to drop course without receiving a grade Nov 11 Last date to submit Fall term work Dec 5 Fall classes end Dec 5 “The best way to predict the future is to invent it” – Alan Kay “We stand now at the intersection of lure and blur. The future beckons, but we’re only partway through inventing it. We can see the outlines of a new art form, but its grammar is as tenuous and elusive as the grammar of cinema a century ago.” – Frank Rose Course Description This course examines the shift from traditional cinematic spectacles to works probing the frontiers of interactive, performative, and networked media. Drawing upon a broad range of scholarship, including film theory, communication studies, cultural studies and new media theory, the course will consider how digital technologies are transforming the semiotic fabric of contemporary visual cultures. The great realist film theorist André Bazin predicted that the future of cinema would be a holographic form without boundaries. In this moment Bazin’s vision is begining to be realized, but co-exists with its opposite: frames within frames that foreground the materiality of the screen. -

Immersion in Interactive Documentaries: a Game-Studies-Driven Approach in a Case Study of Bear 71

IMMERSION IN INTERACTIVE DOCUMENTARIES: A GAME-STUDIES-DRIVEN APPROACH IN A CASE STUDY OF BEAR 71 Simo Hakalisto University of Tampere Faculty of Communication Sciences (COMS) Master’s Degree Programme in Internet and Game Studies Master’s Thesis December 2017 UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE, Faculty of Communication Sciences (COMS) Master’s Degree Programme in Internet and Game Studies HAKALISTO, SIMO: Immersion in Interactive Documentaries: A Game-Studies-Driven Approach in a Case Study of Bear 71 Master’s thesis, 78 pages, 7 pages of appendices December 2017 Interactive documentaries can engage and involve their users in ways differing from traditional narrative-affective viewing experience of a documentary film. Interactive platforms can encourage for example more participative, kinaesthetic, playful and social interaction. However, interactive documentaries have in some degree failed to find and engage their users. Consequently, understanding the variety of users’ experiences with interactive documentaries has become increasingly important. The purpose of this thesis is to provide understanding of the variety of user engagement and immersion in interactive documentaries through a case study of NFB’s web-based interactive documentary Bear 71. Since interactive documentaries and games share increasingly similar characteristics, a game immersion studies framework, Calleja’s Player Involvement Model, is applied in the study. Immersion and the means to engage with documentary artefact are closely related to textual interpretation and meaning- making. Thus, the study combines methodologies from interactive documentary reception studies and game immersion studies to create methodological triangulation suitable for understanding different aspects of immersive interactive documentary experience. Two main modes of immersion were found in the case study, i.e. -

Non-Linearity, Multiple Points of View and Intercultural Understanding. Interactive Documentaries As Sets of Possibilities to Ta

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Anna Wiehl; Judith Aston Non-linearity, multiple points of view and intercultural understanding. Interactive documentaries as sets of possibilities to tackle the complexities of 21st century's socio-cultural reality 2016 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3644 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Wiehl, Anna; Aston, Judith: Non-linearity, multiple points of view and intercultural understanding. Interactive documentaries as sets of possibilities to tackle the complexities of 21st century's socio-cultural reality. In: AugenBlick. Konstanzer Hefte zur Medienwissenschaft. Heft 65/66: Die Herstellung von Evidenz (2016), S. 113– 118. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3644. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. -

Nfb Films and Photos at Montréal-Trudeau Airport Shine Spotlight on Montreal

NFB FILMS AND PHOTOS AT MONTRÉAL-TRUDEAU AIRPORT SHINE SPOTLIGHT ON MONTREAL Montreal, May 11, 2011 – What has brought two such very different Canadian institutions together? The desire to make Canadian art by local artists accessible to Canadians and visitors. Aéroports de Montréal (ADM) and the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) have joined forces to show NFB photographs, films and animated works at Montréal-Trudeau Airport under the Montréal Identity program, better known as L’Aérogalerie. Over the next year or so, three locations at the terminal will be the venue for selected works specially adapted for the occasion. The NFB’s French Program is also considering producing original works for Aéroports de Montréal. “Once again, the NFB is finding innovative ways to make its works accessible to as many people as possible. With this new partnership, the NFB and ADM are offering some 13 million visitors to the air terminal a unique cultural experience and a novel way of viewing Montreal and the work of great Canadian creators, whether expressed through conventional film techniques, animation or multimedia,” said Tom Perlmutter, Government Film Commissioner and Chairperson of the National Film Board of Canada. “The exhibition is part of the Montréal Identity program, also known as L’Aérogalerie, an initiative that we implemented in 2005 with the aim of infusing the airport facilities with a typically ‘Montreal’ character, as well as helping support the city’s artistic and cultural development. Our partnership with the NFB will enhance the program. I know our passengers will love these films and photographs,” said Christiane Beaulieu, ADM’s Vice President of Public Affairs and Communications. -

Future of Storytelling and Museum of the Moving Image Announce Immersive Media Exhibition 'Sensory Stories'

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FUTURE OF STORYTELLING AND MUSEUM OF THE MOVING IMAGE ANNOUNCE IMMERSIVE MEDIA EXHIBITION ‘SENSORY STORIES’ Featuring seventeen virtual-reality and interactive works that engage sight, hearing, touch, and smell April 18–July 26, 2015 New York, New York, April 14, 2015—Museum of the Moving Image and the Future of StoryTelling present Sensory Stories, an exhibition that reveals how an emerging group of artists and companies are using innovative digital techniques to change the way audiences experience storytelling. The exhibition, which includes virtual-reality experiences, interactive films, participatory installations, and new touch responsive interfaces, opens on April 18, 2015, and will be on view through July 26, 2015, at the Museum. “Technology has driven the evolution of moving image entertainment since the invention of film,” said Carl Goodman, the Museum’s Executive Director. “Today, new technologies and interfaces aim to bring the body, mind, and senses into a new relationship with the moving image, one which eliminates the gap between the real and the virtual, the physical and the digital. We asked Future of Storytelling to develop an exhibition for the Museum because of their unique expertise in these important developments.” Conceived and organized by the Future of StoryTelling (FoST), Sensory Stories invites visitors to participate in narratives that merge traditional storytelling with groundbreaking new technologies, incorporating full-body immersion, and interaction that includes sight, hearing, touch, -

Surviving Progress

SURVIVING PROGRESS DIRECTOR Mathieu ROY CO-DIRECTOR Harold CROOKS PRODUCED BY Daniel LOUIS Denise ROBERT WRITTEN BY Harold CROOKS & Mathieu ROY EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS Mark ACHBAR BIG PICTURE MEDIA CORPORATION Betsy CARSON PRODUCER Gerry FLAHIVE NFB EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Silva BASMAJIAN NFB EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS Martin SCORSESE Emma TILLINGER KOSKOFF SURVIVING PROGRESS SYNOPSIS Every time history repeats itself the price goes up. Surviving Progress presents the story of human advancement as awe-inspiring and dou- ble-edged. It reveals the grave risk of running the 21st century’s software — our know- how — on the ancient hardware of our primate brain which hasn’t been upgraded in \HDUV:LWKULFKLPDJHU\DQGLPPHUVLYHVRXQGWUDFNÀOPPDNHUV0DWKLHX5R\DQG Harold Crooks launch us on journey to contemplate our evolution from cave-dwellers to space explorers. 5RQDOG:ULJKWZKRVHEHVWVHOOHU´$6KRUW+LVWRU\2I3URJUHVVµLQVSLUHGWKLVÀOPUHYHDOV KRZFLYLOL]DWLRQVDUHUHSHDWHGO\GHVWUR\HGE\´SURJUHVVWUDSVµ³DOOXULQJWHFKQRORJLHV serve immediate needs, but ransom the future. With intersecting stories from a Chinese FDUGULYLQJ FOXE D :DOO 6WUHHW LQVLGHU ZKR H[SRVHV DQ RXWRIFRQWURO HQYLURQPHQWDOO\ UDSDFLRXVÀQDQFLDOHOLWHDQGHFRFRSVGHIHQGLQJDVFRUFKHG$PD]RQWKHÀOPOD\VVWDUN evidence before us. In the past, we could use up a region’s resources and move on. But if today’s global civilization collapses from over-consumption, that’s it. We have no back-up planet. Surviving Progress brings us thinkers who have probed our primate past, our brains, DQGRXUVRFLHWLHV6RPHDPSOLI\:ULJKWҋVXUJHQWZDUQLQJZKLOHRWKHUVKDYHIDLWKWKDWWKH -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2014–2015 © 2016 National Film Board of Canada Published by Strategic Planning and Government Relations P.O. Box 6100, Station Centre-ville Montreal, Quebec H3C 3H5 Internet : onf-nfb.gc.ca E-mail: [email protected] Cover page: MCLAREN MUR À MUR (McLaren Wall-to-Wall), Quartier des spectacles | NFB, Montreal ISBN 0-7722-1276-7 1st Quarter 2016 Printed in Canada TABLE OF CONTENTS IN NUMBERS GOVERNMENT FILM COMMISSIONER’S MESSAGE FOREWORD HIGHLIGHTS AWARDS GOVERNANCE MANAGEMENT SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Annex I: NFB ACROSS CANADA Annex II: PRODUCTIONS Annex III: INDEPENDENT FILM PROJECTS SUPPORTED BY ACIC AND FAP FRAME X FRAME: ANIMATED FILM AT THE NFB Exhibit at Musée de la civilisation, Quebec City Photo: Jessy Bernier, Perspective Photo, 0148_relv_0001 December 4, 2015 The Honourable Mélanie Joly Minister of Canadian Heritage Ottawa, Ontario Minister: I have the honour of submitting to you, in accordance with the provisions of sec- tion 20(1) of the National Film Act, the Annual Report of the National Film Board of Canada for the period ended March 31, 2015. The report also provides highlights of noteworthy events of this fiscal year. Yours respectfully, Claude Joli-Coeur Government Film Commissioner and Chairperson of the National Film Board of Canada IN NUMBERS CAMPUS, A POWERFUL TEACHING TOOL FOR THE 21ST-CENTURY CLASSROOM P.4 | 2014-2015 2014–2015 – IN NUMBERS 61 10 5 3 original NFB films interactive public applications and co-productions websites installations for tablets digital documents supporting