Survey of American Literature I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawthorne's Concept of the Creative Process Thesis

48 BSI 78 HAWTHORNE'S CONCEPT OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Retta F. Holland, B. S. Denton, Texas December, 1973 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. HAWTHORNEIS DEVELOPMENT AS A WRITER 1 II. PREPARATION FOR CREATIVITY: PRELIMINARY STEPS AND EXTRINSIC CONDITIONS 21 III. CREATIVITY: CONDITIONS OF THE MIND 40 IV. HAWTHORNE ON THE NATURE OF ART AND ARTISTS 67 V. CONCLUSION 91 BIBLIOGRAPHY 99 iii CHAPTER I HAWTHORNE'S DEVELOPMENT AS A WRITER Early in his life Nathaniel Hawthorne decided that he would become a writer. In a letter to his mother when he was seventeen years old, he weighed the possibilities of entering other professions against his inclinations and concluded by asking her what she thought of his becoming a writer. He demonstrated an awareness of some of the disappointments a writer must face by stating that authors are always "poor devils." This realistic attitude was to help him endure the obscurity and lack of reward during the early years of his career. As in many of his letters, he concluded this letter to his mother with a literary reference to describe how he felt about making a decision that would determine how he was to spend his life.1 It was an important decision for him to make, but consciously or unintentionally, he had been pre- paring for such a decision for several years. The build-up to his writing was reading. Although there were no writers on either side of Hawthorne's family, there was a strong appreciation for literature. -

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

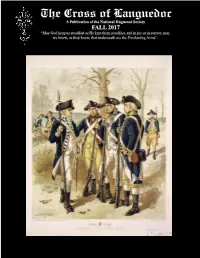

FALL 2017 “May God Keep Us Steadfast As He Kept Them Steadfast, and in Joy Or in Sorrow, May We Know, As They Knew, That Underneath Are the Everlasting Arms”

The Cross of Languedoc A Publication of the National Huguenot Society FALL 2017 “May God keep us steadfast as He kept them steadfast, and in joy or in sorrow, may we know, as they knew, that underneath are the Everlasting Arms”. COVER FEATURE – HUGUENOTS IN THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR By Editor Janice Murphy Lorenz, J.D. Cover Feature image: Infantry: Continental Army, 1779-1783, artist Henry Alexander Ogden; lithograph by G. H. Buek & Col, NY, c1897; edited by Janice Murphy Lorenz. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Expired copyright by Brig. Gen’l S.B. Holabird, Qr. Master Gen’l, U.S.A. Three of the most important values in Huguenot culture are freedom of conscience, patriotism, and courage of conviction. That is why so many men and women of Huguenot descent are prominent in the annals of early American history. One example is the many different ways in which Huguenots contributed to the American cause in the Revolutionary War. As might be imagined from regarding cover lithograph of four soldiers, which depicts the uniforms and weapons used during the period 1779 to 1783, fathers, sons, brothers and cousins fought in the war on both sides, according to their conscience. The following article from 1894 clearly emphasizes the Huguenots’ patriotic service to America’s freedom, while mentioning that some were Loyalists, too. On later pages, you will find a list prepared by Genealogist General Nancy Wright Brennan of approved Huguenot ancestors and their descendants whose patriotic service has been recognized in the patriots database maintained by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). -

F, Sr.Auifuvi

NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE' S USE OF WITCH AND DEVIL LORE APPROVED: Major Professor Consulting Professor Iinor Professor f, sr. auifUvi Chairman of" the Department of English Dean of the Graduate School Robb, Kathleen A., Nathaniel Hawthorne;s Fictional Use of Witch and Devil Lore. Master of Arts (English), December, - v 1970, 119 pp., bibliography, 19 titles. Nathaniel Hawthorne's personal family history, his boy- hood in the Salem area of New England, and his reading of works about New England's Puritan era influenced his choice of witch and Devil lore as fictional material. The witch- ci"aft trials in Salem were evidence (in Hawthorne's inter- pretation) of the errors of judgment and popular belief which are ever-present in the human race. He considered the witch and Devil doctrine of the seventeenth century to be indicative of the superstition, fear, and hatred which governs the lives of men even in later centuries. From the excesses of the witch-hunt period of New England history Hawthorne felt moral lessons could be derived. The historical background of witch and Devil lore, while helpful in illustrating moral lessons, is used by Hawthorne to accomplish other purposes. The paraphernalia of witchcraft with its emphasis on terrible and awesome ceremonies or practices such as Black Sabbaths, Devil compacts, image-magic, spells and curses, the Black Man in'the forest, spectral shapes, and familiar spirits is used by Hawthorne to add atmospheric qualities to his fiction. Use of the diabolic creates the effects of horror, suspense, and mystery. Furthermore, such 2 elements of witch and Devil doctrine (when introduced in The Scarlet Letter, short stories, and historical sketches) also provide an aura of historical authenticity, thus adding a v dimension of reality and concreteness to the author's fiction. -

A Bibliography of Edwin Arlington Robinson, 1941-1963

Colby Quarterly Volume 7 Issue 1 March Article 3 March 1965 A Bibliography of Edwin Arlington Robinson, 1941-1963 William White Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 7, no.1, March 1965, p.1-26 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. White: A Bibliography of Edwin Arlington Robinson, 1941-1963 Colby Library Quarterly Series VII March 1965 No.1 A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF EDWIN ARLINGTON ROBINSON, 1941-1963 By WILLIAM WHITE HIS bibliography of Edwin Arlington Robinson is a supple T ment to Charles Beecher Hogan's "Edwin Arlington Robin son: New Bibliographical Notes," The Papers of the Biblio graphical Society of America (New York), Vol. XXXV, pp. 115-144, Second Quarter 1941, which itself supplements Mr. Hogan's admirable A Bibliography of Edwin Arlington Robin son (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936). I have fol lowed Mr. Hogan's organization and style, with some slight modifications, particularly in the descriptions of books by Robinson. Although an attempt has been made to be as com plete as possible, I certainly do not approach Mr. Hogan's work in this respect. While he says (on p. iii of his Bibliography) that his book is "intended primarily for collectors," the present supplement is meant for scholars and critics who would like to know what has been written on the creator of "Luke Havergal" and "Miniver Cheevy" in the past t\venty-two years. -

April Showers

PARTART 2 Realism and Naturalism Mrs. Charles Thursby, 1897–1898. John Singer Sargent. 3 Oil on canvas, 78 x 39 /4 in. Collection of The Newark Museum. “There are two ways of spreading light: to be The candle or the mirror that reflects it.” —Edith Wharton, “Vesalius in Zante” 531 The Newark Museum/Art Resource, NY 0531 U4P2-845481.indd 531 4/7/06 6:06:33 PM LITERARY HISTORY The Two Faces of Urban America N THE LATE NINETEENTH AND EARLY twentieth centuries, despite the emergence of a Igrowing middle class, rapid industrialization created two sharply contrasting urban classes: wealthy entrepreneurs and poor immigrants from Europe and Asia who provided them with cheap labor. Although dependent upon each other, these two groups seldom met, as they lived in starkly different neighborhoods. The wealthiest families established fashionable districts in the hearts of cities, where they built fabulous mansions. By contrast, the majority of factory workers squeezed into dark, overcrowded tenements where crime, violence, fire, and disease were constant threats. U.S. writers of the time responded to and reflected these urban conditions in their novels, stories, essays, and articles. Picnicking in Central Park, 1885. Robert L. Bracklow. Black and white photograph. “The entire metropolitan center possessed a high and mighty air her heroine Lily Bart’s descent from wealth into poverty is mirrored by a decline in the houses she is calculated to overawe and abash the forced to inhabit. common applicant, and to make the Wharton’s older contemporary and friend Henry James gulf between poverty and success was born into a distinguished Boston family in 1843. -

Edwin Arlington Robinson's Interpretation of Tristram

/ EDWIN ARLINGTON ROBINSON’S INTERPRETATION OF TRISTRAM BY MARY EDNA MOLSEED 'r A THESIS Submitted to the Faculty of The Creighton University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of E n g l i s h OMAHA, 1937 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE F O R E W O R D ................................................. i I. AN INTRODUCTION TO ROBINSON .......................... 1 II. THE POSSIBLE ORIGIN OF THE TRISTRAM L E G E N D ..................................................... 13 III. SOME CHARACTERISTICS OF THE TRISTAN STORY BY THOMAS ........................................ 19 IV. LATER VERSIONS OF TRISTRAM .......................... 24 V. ROBINSON'S INTERPRETATION OF TRISTRAM .............33 BIBLIOGRAPHY 44 i FOREWORD ■ The third great epic, Tristram, which was to complete the Arthurian trilogy, so majestically and movingly in terpreted the world-famous medieval romance that the out standing excellences of Robinson's verse, thus far ignored by the large reading public, forced themselves into recognition, and he, after thirty years' patient waiting and unflagging trust in his own genius, at last was greeted with universal applause. Although America in the interval had witnessed an exceptional efflorescence of good poetry, he was hailed, not only as the dean, but as the prince of American bards.* The writer, who considers this statement as valid, bases her thesis on the premise that Robinson did appeal to the modem reader. She aims, first, through a study of the poet in general, to show how he appealed to the public. Because Tristram is classed as a medieval character, she will consider the possible origin of the story. -

Hawthorne's Conception of History: a Study of the Author's Response to Alienation from God and Man

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1979 Hawthorne's Conception of History: a Study of the Author's Response to Alienation From God and Man. Lloyd Moore Daigrepont Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Daigrepont, Lloyd Moore, "Hawthorne's Conception of History: a Study of the Author's Response to Alienation From God and Man." (1979). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3389. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3389 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

E.-Michael-Jones-Hawthorne-The-Angel-And-The-Machine.Pdf

FAITH & REASON THE JOURNAL OF CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE Fall 1982 | Vol. VIII, No. 3 Hawthorne: The Angel and the Machine E. Michael Jones Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864) is justly famous as one of America’s premier novelists and short story writers. Over a writing career stretching from 1829 until his death, Hawthorne consistently probed the moral and spiritual conficts which he observed in his own life and, mainly, in the lives of the Puritan and Transcendentalist New Englanders with whom he spent most of his life. Both Puritanism and Transcendentalism, of course, deal with the material world and the human body in ways which tend to make them either confict with or irrelevant to the human spirit. Therefore, Hawthorne was never far in his works from a struggle with the fundamental identity of man as a unity of body and soul. As Michael Jones points out below The Blithedale Romance is a novel uniquely situated in Haw- thorne’s life and experience to lend itself to an illuminating examination of the confict within the author about human na- ture. This examination in turn sheds light on a whole chapter of American history as well as some of the recurring spiritual tensions of our own time. “He is a man, after all!” thought I--his Maker’s own truest image, a philanthropic man!-not that steel engine of the Devil’s contrivance, a philanthropist!”-But, in my wood-walks, and in my silent chamber, the dark face frowned at me again. “We must trust for intelligent sympathy to our guardian angels, if any there be,” said Zenobia. -

James Russell Lowell - Poems

Classic Poetry Series James Russell Lowell - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive James Russell Lowell(22 February 1819 – 12 August 1891) James Russell Lowell was an American Romantic poet, critic, editor, and diplomat. He is associated with the Fireside Poets, a group of New England writers who were among the first American poets who rivaled the popularity of British poets. These poets usually used conventional forms and meters in their poetry, making them suitable for families entertaining at their fireside. Lowell graduated from Harvard College in 1838, despite his reputation as a troublemaker, and went on to earn a law degree from Harvard Law School. He published his first collection of poetry in 1841 and married Maria White in 1844. He and his wife had several children, though only one survived past childhood. The couple soon became involved in the movement to abolish slavery, with Lowell using poetry to express his anti-slavery views and taking a job in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania as the editor of an abolitionist newspaper. After moving back to Cambridge, Lowell was one of the founders of a journal called The Pioneer, which lasted only three issues. He gained notoriety in 1848 with the publication of A Fable for Critics, a book-length poem satirizing contemporary critics and poets. The same year, he published The Biglow Papers, which increased his fame. He would publish several other poetry collections and essay collections throughout his literary career. Maria White died in 1853, and Lowell accepted a professorship of languages at Harvard in 1854. -

Modem Women's Poetry 1910—1929

Modem Women’s Poetry 1910—1929 Jane Dowson Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester. 1998 UMI Number: U117004 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U117004 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Modern Women9s Poetry 1910-1929 Jane Dowson Abstract In tracing the publications and publishing initiatives of early twentieth-century women poets in Britain, this thesis reviews their work in the context of a male-dominated literary environment and the cultural shifts relating to the First World War, women’s suffrage and the growth of popular culture. The first two chapters outline a climate of new rights and opportunities in which women became public poets for the first time. They ran printing presses and bookshops, edited magazines and wrote criticism. They aimed to align themselves with a male tradition which excluded them and insisted upon their difference. Defining themselves antithetically to the mythologised poetess of the nineteenth century and popular verse, they developed strategies for disguising their gender through indeterminate speakers, fictional dramatisations or anti-realist subversions. -

October 9 Update 2FALL 2018 SYLLABUS Engl E 182A POETRY

Poetry in America: From the Mayflower Through Emerson Harvard Extension School: ENGL E-182a (CRN 15383) SYLLABUS | Fall 2018 COURSE TEAM Instructor Elisa New PhD, Powell M. Cabot Professor of American Literature, Harvard University Teaching Instructor Gillian Osborne, PhD ([email protected]) Teaching Fellows Field Brown, PhD candidate, Harvard University ([email protected]) Jacob Spencer, PhD, Harvard University ([email protected]) Course Manager Caitlin Ballotta Rajagopalan, Manager of Online Education, Poetry in America ([email protected]) ABOUT THIS COURSE This course, an installment of the multi-part Poetry in America series , covers American poetry in cultural context through the year 1850. The course begins with Puritan poets—some orthodox, some rebel spirits—who wrote and lived in early New England. Focusing on Anne Bradstreet, Edward Taylor, and Michael Wigglesworth, among others, we explore the interplay between mortal and immortal, Europe and wilderness, solitude and sociality in English North America. The second part of the course spans the poetry of America's early years, directly before and after the creation of the Republic. We examine the creation of a national identity through the lens of an emerging national literature, focusing on such poets as Phillis Wheatley, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Edgar Allen Poe, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, among others. Distinguished guest discussants in this part of the course include writer Michael Pollan, economist Larry Summers, Vice President Al Gore, Mayor Tom Menino, and others. Many of the course segments have been filmed in historic places—at Cape Cod; on the Freedom Trail in Boston; in marshes, meadows, churches, and parlors, and at sites of Revolutionary War battle.