1 Copyright Ellyn L. Bartges 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All-Time Coaching Ledger

all-time coaching ledger JILL HUTCHISON GOOCH FOSTER JENNY YOPP Years Active: 1971-73, 1974-99 Years Active: 1973-74 Years Active: 1999-2003 Record: 461-323 (.588) [28 seasons] Record: 17-4 (.810) [One season] Record: 25-83 (.231) [Four seasons] • Redbird basketball all-time wins • 1974 AIAW State Champions YOPP YEAR-BY-YEAR leader (men’s and women’s). • 1974 AIAW Regional 1999-2000 ..................................6-20 • Three NCAA Tournament bids. Champions 2000-01 ......................................5-22 • Six WNIT bids. • Finished the season ranked 2001-02 ......................................7-20 • Three-time conference coach of No. 12 in the nation 2002-03 ......................................7-21 the year (1985, 1988, 1996). • Coached 13 first-team FOSTER YEAR-BY-YEAR all-conference players, two All- 1973-74 ......................................17-4 Americans and two Olympians. • Illinois State Athletics Hall of Fame member (1984). • Missouri Valley Conference Hall of Fame member (2008). • Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame member (2009). HUTCHISON YEAR-BY-YEAR *1970-71 .....................................13-9 1971-72 ...................................... 11-6 ROBIN PINGETON Years Active: 2003-10 1972-73 ......................................17-5 Record: 144-81 (.640) [Seven seasons] 1974-75 ......................................14-9 MELINDA FISCHER 1975-76 ....................................18-12 Years Active: 1980-85 • Two NCAA Tournament bids 1976-77 ......................................20-6 Record: 113-47 (.810) [Five -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

2010-11 Women's Basketball Game Notes

BRADLEY 2010-11 Women’s Basketball Game Notes Jim Rea, Associate Director of Communications • O: (309) 677-3869 • C: (309) 256-4379 • F: (309) 677-2626 • E-Mail: [email protected] • www.BradleyBraves.com Bradley University Quick Facts This Week In Bradley Women’s Basketball General Information Game #10 Location Peoria, Ill. Bradley Braves (6-3 overall) Founded 1897 vs. Northern Illinois Huskies (5-5 overall) Enrollment 5,801 Renaissance Coliseum (4,200) • Peoria, Ill. Type Co-educational, private Saturday, December 18, 2010 • 7:05 p.m. Affiliation NCAA Division I-AAA Television: None vs. Conference Missouri Valley Radio: 1290 AM WIRL Athletics Nickname Braves Internet: Live video & audio streams at http://www.bradleybraves.com/liveEvents/liveEvents.dbml?DB_OEM_ID=3400 Colors Red (PMS 186) and White Live Stats: http://www.bubraves.com/liveStats/liveStats.dbml?&DB_OEM_ID=3400 President Joanne K. Glasser, Esq. Series History: NIU leads 7-4 Director of Athletics Michael Cross, PhD Last Meeting: NIU won 86-73 in DeKalb, Ill., on Nov. 13, 2009 Executive Associate A.D./SWA Virnette House-Browning For Starters three starters from last year’s squad which finished 10-19 Bradley (6-3 overall) plays its first game after finals at home overall and was fifth in the West Division of the Mid-American Basketball Information Saturday against Northern Illinois before kicking off a three- Conference (4-12). Bradley and NIU have one common opponent Home Arena Renaissance Coliseum game road swing next week. The Braves bring a three-game to date in Western Illinois, with both teams picking up road Capacity 4,200 win streak into the contest with the Huskies and have won five wins in Macomb against the Leathernecks. -

Interview with Lorene Ramsey # DGB-V-D-2004-013 Interview Date: October 18, 2004 Interviewer: Ellyn Bartges

Interview with Lorene Ramsey # DGB-V-D-2004-013 Interview Date: October 18, 2004 Interviewer: Ellyn Bartges COPYRIGHT The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of either Ellyn Bartges (Interviewer) or the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 A Note to the Reader This transcript is based on an interview recorded by Ellyn Bartges. Readers are reminded that the interview of record is the original video or audio file, and are encouraged to listen to portions of the original recording to get a better sense of the interviewee's personality and state of mind. The interview has been transcribed in near-verbatim format, then edited for clarity and readability, and reviewed by the interviewee. For many interviews, the ALPL Oral History Program retains substantial files with further information about the interviewee and the interview itself. Please contact us for information about accessing these materials. This is a copy of the interview that I had with Lorene Ramsey from Illinois Central College, former basketball and head softball coach there for thirty-four years. The interview took place on October 18, 2004, and I'm transferring it over from an RCA recorder for sound quality. Bartges: It is October eighteenth here at Illinois Central College, and I am interviewing Lorene Ramsey, former head women's basketball and softball coach at ICC [Illinois Central College], and she currently resides in Arizona. -

Girls' Sports Reading List

Girls’ Sports Reading List The books on this list feature girls and women as active participants in sports and physical activity. There are books for all ages and reading levels. Some books feature champion female athletes and others are fiction. Most of the books written in the 1990's and 2000’s are still in print and are available in bookstores. Earlier books may be found in your school or public library. If you cannot find a book, ask your librarian or bookstore owner to order it. * The descriptions for these books are quoted with permission from Great Books for Girls: More than 600 Books to Inspire Today’s Girls and Tomorrow’s Women, Kathleen Odean, Ballantine Books, New York, 1997. ~ The descriptions for these books are quoted from Amazon.com. A Turn for Lucas, Gloria Averbuch, illustrations by Yaacov Guterman, Mitten Press, Canada, 2006. Averbuch, author of best-selling soccer books with legends like Brandi Chastain and Anson Dorrance, shares her love of the game with children in this book. This is a story about Lucas and Amelia, the soccer-playing twins who share this love of the game. A Very Young Skater, Jill Krementz, Dell Publishing, New York, NY, 1979. Ages 7-10, 52 p., ($6.95). The story of a 10-year-old female skater told in words and pictures. A Winning Edge, Bonnie Blair with Greg Brown, Taylor Publishing, Dallas, TX, 1996. Ages 8- 12, 38 p., ($14.95). Bonnie Blair shares her passion and motivation for skating, the obstacles that she’s faced, the sacrifices and the victories. -

She Rose from Nothing to Become the Decorated Head Coach for Women's Track and Field at the University of Texas, Winning

b y m i m i s w a r t z FAILURE is not AN OPTION She rose from nothing to become the decorated head coach for women’s track and field at the University of Texas, winning six NCAA championships, sending countless athletes to the Olympics, and turning the school’s program into the country’s standard for excellence. Then Bev Kearney was abruptly forced to resign because of an illicit affair. But she didn’t get to where she is by giving up without a fight. PORTRAITS BY MICHAEL CROUSER because you have to, because you long for Olympic gold medalist Sanya Richards- movement—the sight of tall pines shooting Ross. Inside the stadium, they crammed Imagine, for a moment, that you are sev- by as you fly down a dirt road. That move- into the bleachers to watch as the runners enteen, just a slip of a thing, all elbows and ment is home. burned up the track, wearing uniforms in knees but with bright, determined eyes. At electric shades of purple and red, green and the mercy of your mama, you have lived in yellow—and, for UT, bright white. so many places and gone to so many schools It was a mostly black crowd, unusual you can’t remember them all. Mississippi, March 30, 2013, in Austin was the kind in Austin, maybe, but not in the world of California, Illinois, Nebraska. Sometimes of spring day that portends the unbear- track and field, a sport dominated in the you and your little brother spend all day hid- able summer to come. -

Effort Reversal

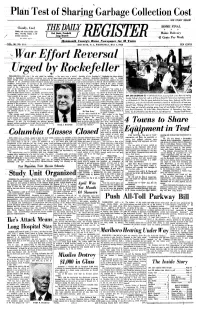

Test of Sharing Garbage Collection Cost SEE STORY BELOW Cloudy, Cool * * * Cloudy and unseasonably cool today. Clearing tonight, A bit Home Delivery warmer tomorrow. (See Details, Page 2) ' ' 45 Gents Per Week Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 89 Years 1,1968 ' TEN CENTS .. Effort Reversal PHILADELPHIA (AP)-Gov. He also called for building —"We must seek a settle- Speaking of the President's Regarding the Asian nations, Nelson A. • Rockefeller, in the and protecting local govern- ment whose aims and guaran- peace initiative, Rockefeller Rockefeller said "a lasting major foreign policy address ments, and broadening of the tees safeguard the freedom and said "I do not believe that this peace must embrace the lives promised in his presidential South Vietnamese national gov- security of all Southeast Asia." time of renewed hope is a time of all the hundreds of millions candidacy announcement yes- ernment in his speech be/ore tc stand in silence"—an appar living in the great crescent terday, today called for a re- the World Affairs Council of ent reference to the Vietnam from | Japan throughout India versal of the "Americaniza- Philadelphia. stand of Richard M. Nixon, his to Iran." tion" of the Vietnam war ef- His remarks were prepared only major rival for the Re He urged "our calling of a fort and the convening of a for delivery. publican nomination. conference of all these govern- ' council of Asian nations to work Rockefeller praised President The governor declared: "We ments to discuss and to define for economic progress and po- Johnson for "his initiative in must, before the world at large, joint efforts for fostering eco- litical stability in the area. -

Your Nonprofit Community News Source Since 1958

LETTERS Your nonprofit community news source since 1958 CONTINUED FROM PAGE 6 home be built without a thorough that new middle-income families are Vote yes on amendment and and complete review, including water just not able to make it work. The Town Plan articles supply, wastewater, traffic safety etc., etc. Some of you know this very well, Many of you know that I have focused Dear Charlotte friends and neighbors, while others possibly do not know since my historic community service time you may be newer residents. on land conservation, and with great Charlotte News I am calling with a sense of urgency success, largely because Charlotte is Thursday, February 11, 2021 | Volume LXIII Number 16 to ask that you please become well In this new round of plan and blessed with abundant and fabulous informed about the town plan and regulation updates for the East Village, nature to nurture. And largely because regulation articles coming up for vote the proposed village-related articles our town has a generous desire to give this year at town meeting. I am reaching are simply proposing potential to allow money to protect our natural assets. out to friends and neighbors right now for a modest amount of new homes This richness is only a problem if we to say: VOTE YES in support of the to be built on one-acre lots (vs less do not provide for an economically and proposed articles on Town Meeting affordable five-acre lots) in the village socio-diverse community. For the sake Day. commercial district only. -

The Daily Egyptian, December 12, 1979

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC December 1979 Daily Egyptian 1979 12-12-1979 The aiD ly Egyptian, December 12, 1979 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_December1979 Volume 64, Issue 72 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, December 12, 1979." (Dec 1979). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1979 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in December 1979 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Daily 73gyptian Wednesday. December !2. 1m-Vol. 64. No. n Southern Illinois University Gus says wben Maee gets through dlnying up tbe athletics fee. some aibletes wiD be more equal than others. lAC endorses proposed increase in athletics fee By Paula Donner Walter' November board meeting that mentioocd that the Faculty Although Women's Athletics of the Admi"strat:ve and Staff Writer an audit of the athletics Senate asked that the board Director Charlotte West did not Professional Council, all voted The Intercollegiate AthletICS department would be con- delay action unless the increase specifically say she was in favor 1.1 oppose the fee increase "at Committee voted Tuesday to ducted. At that time, Lesar said is supported by a student of the increase, she implied the this time." That motion was recommend that the Sill Board he did not expect the audit to be. referendum. Brown was pdr need for it. citing the lil"ited defeated. 6-4, of Trustees apprt've the completed by the December ticipating in the lAC weeling as budget of her program. -

2003 NCAA Women's Basketball Records Book

AwWin_WB02 10/31/02 4:47 PM Page 99 Award Winners All-American Selections ................................... 100 Annual Awards ............................................... 103 Division I First-Team All-Americans by Team..... 106 Divisions II and III First-Team All-Americans by Team ....................................................... 108 First-Team Academic All-Americans by Team.... 110 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners by Team ....................................................... 112 AwWin_WB02 10/31/02 4:47 PM Page 100 100 ALL-AMERICAN SELECTIONS All-American Selections Annette Smith, Texas; Marilyn Stephens, Temple; Joyce Division II: Jennifer DiMaggio, Pace; Jackie Dolberry, Kodak Walker, LSU. Hampton; Cathy Gooden, Cal Poly Pomona; Jill Halapin, Division II: Carla Eades, Central Mo. St.; Francine Pitt.-Johnstown; Joy Jeter, New Haven; Mary Naughton, Note: First selected in 1975. Voted on by the Women’s Perry, Quinnipiac; Stacey Cunningham, Shippensburg; Stonehill; Julie Wells, Northern Ky.; Vanessa Wells, West Basketball Coaches Association. Claudia Schleyer, Abilene Christian; Lorena Legarde, Port- Tex. A&M; Shannon Williams, Valdosta St.; Tammy Wil- son, Central Mo. St. 1975 land; Janice Washington, Valdosta St.; Donna Burks, Carolyn Bush, Wayland Baptist; Marianne Crawford, Dayton; Beth Couture, Erskine; Candy Crosby, Northeast Division III: Jessica Beachy, Concordia-M’head; Catie Immaculata; Nancy Dunkle, Cal St. Fullerton; Lusia Harris, Ill.; Kelli Litsch, Southwestern Okla. Cleary, Pine Manor; Lesa Dennis, Emmanuel (Mass.); Delta St.; Jan Irby, William Penn; Ann Meyers, UCLA; Division III: Evelyn Oquendo, Salem St.; Kaye Cross, Kimm Lacken, Col. of New Jersey; Louise MacDonald, St. Brenda Moeller, Wayland Baptist; Debbie Oing, Indiana; Colby; Sallie Maxwell, Kean; Page Lutz, Elizabethtown; John Fisher; Linda Mason, Rust; Patti McCrudden, New Sue Rojcewicz, Southern Conn. St.; Susan Yow, Elon. -

Women's Basketball Award Winners

WOMEN’S BASKETBALL AWARD WINNERS All-America Teams 2 National Award Winners 15 Coaching Awards 20 Other Honors 22 First Team All-Americans By School 25 First Team Academic All-Americans By School 34 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners By School 39 ALL-AMERICA TEAMS 1980 Denise Curry, UCLA; Tina Division II Carla Eades, Central Mo.; Gunn, BYU; Pam Kelly, Francine Perry, Quinnipiac; WBCA COACHES’ Louisiana Tech; Nancy Stacey Cunningham, First selected in 1975. Voted on by the Wom en’s Lieberman, Old Dominion; Shippensburg; Claudia Basket ball Coaches Association. Was sponsored Inge Nissen, Old Dominion; Schleyer, Abilene Christian; by Kodak through 2006-07 season and State Jill Rankin, Tennessee; Lorena Legarde, Portland; Farm through 2010-11. Susan Taylor, Valdosta St.; Janice Washington, Valdosta Rosie Walker, SFA; Holly St.; Donna Burks, Dayton; 1975 Carolyn Bush, Wayland Warlick, Tennessee; Lynette Beth Couture, Erskine; Baptist; Marianne Crawford, Woodard, Kansas. Candy Crosby, Northern Ill.; Immaculata; Nancy Dunkle, 1981 Denise Curry, UCLA; Anne Kelli Litsch, Southwestern Cal St. Fullerton; Lusia Donovan, Old Dominion; Okla. Harris, Delta St.; Jan Pam Kelly, Louisiana Tech; Division III Evelyn Oquendo, Salem St.; Irby, William Penn; Ann Kris Kirchner, Rutgers; Kaye Cross, Colby; Sallie Meyers, UCLA; Brenda Carol Menken, Oregon St.; Maxwell, Kean; Page Lutz, Moeller, Wayland Baptist; Cindy Noble, Tennessee; Elizabethtown; Deanna Debbie Oing, Indiana; Sue LaTaunya Pollard, Long Kyle, Wilkes; Laurie Sankey, Rojcewicz, Southern Conn. Beach St.; Bev Smith, Simpson; Eva Marie St.; Susan Yow, Elon. Oregon; Valerie Walker, Pittman, St. Andrews; Lois 1976 Carol Blazejowski, Montclair Cheyney; Lynette Woodard, Salto, New Rochelle; Sally St.; Cindy Brogdon, Mercer; Kansas. -

2012 DC Program.Pub

Rotary District 7680 2012 Conference April 20-22, 2012 Asheville, NC Renaissance—Asheville District Governor—H. Allen Langley What’s in it for ME?!? C.A.R.T. Fund Raiser With the Kannapolis Intimidators! Mark Your Calendar for Sunday, JUNE 3! District 7680 at the Kannapolis In- timidators Gametime: 5:05pm with Family of Rotary Fellowship Proceeds to benefit the Coins for Alz- heimer’s Research Trust (CART) Fund! For more information contact Karen Shore (contact information is in the District and Club Database) 2 Paul P. Harris, a lawyer, was the founder of Rotary, the world's first and most international service club. Born in Racine Wisconsin, USA on 19 April 1868, Paul was the second of six children to George N. Harris and Corne- lia Bryan Harris. At age 3 he moved to Wallingford, Vermont where he grew up in the care of his paternal grandparents. Married to Jean Thompson Harris (1881 - 1963), they had no children. He re- ceived an L.L.B. from the University of Iowa and received an honorary L.L.D. from the University of Vermont. Paul Harris worked as a newspaper re- porter, a business teacher, stock com- pany actor, cowboy, and traveled exten- sively in the U.S.A. and Europe selling marble and granite. In 1896, he went to Chicago to practice law. One eve- ning Paul visited the suburban home of a professional friend. After dinner, as they strolled through the neighborhood, Paul's friend introduced him to various tradesmen in their stores. It was here Paul conceived the idea of a club that could recapture some of the friendly spirit among business- men in small communities.