Renewable Energy Through Agency Action Amy L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tesla Motors

AUGUST 2014 TESLA MOTORS: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY, OPEN INNOVATION, AND THE CARBON CRISIS DR MATTHEW RIMMER AUSTRALIAN RESEARCH COUNCIL FUTURE FELLOW ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF LAW The Australian National University College of Law, Canberra, ACT, 0200 Work Telephone Number: (02) 61254164 E-Mail Address: [email protected] 1 Introduction Tesla Motors is an innovative United States manufacturer of electric vehicles. In its annual report for 2012, the company summarizes its business operations: We design, develop, manufacture and sell high-performance fully electric vehicles and advanced electric vehicle powertrain components. We own our sales and service network and have operationally structured our business in a manner that we believe will enable us to rapidly develop and launch advanced electric vehicles and technologies. We believe our vehicles, electric vehicle engineering expertise, and operational structure differentiates us from incumbent automobile manufacturers. We are the first company to commercially produce a federally-compliant electric vehicle, the Tesla Roadster, which achieves a market-leading range on a single charge combined with attractive design, driving performance and zero tailpipe emissions. As of December 31, 2012, we had delivered approximately 2,450 Tesla Roadsters to customers in over 30 countries. While we have concluded the production run of the Tesla Roadster, its proprietary electric vehicle powertrain system is the foundation of our business. We modified this system -

Comparative Review of a Dozen National Energy Plans: Focus on Renewable and Efficient Energy

Technical Report A Comparative Review of a Dozen NREL/TP-6A2-45046 National Energy Plans: Focus on March 2009 Renewable and Efficient Energy Jeffrey Logan and Ted L. James Technical Report A Comparative Review of a Dozen NREL/TP-6A2-45046 National Energy Plans: Focus on March 2009 Renewable and Efficient Energy Jeffrey Logan and Ted L. James Prepared under Task No. SAO7.9C50 National Renewable Energy Laboratory 1617 Cole Boulevard, Golden, Colorado 80401-3393 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC Contract No. DE-AC36-08-GO28308 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. Available electronically at http://www.osti.gov/bridge Available for a processing fee to U.S. -

Beyond Solyndra: Examining the Department of Energy's Loan Guarantee Program Hilary Kao

William & Mary Environmental Law and Policy Review Volume 37 | Issue 2 Article 4 Beyond Solyndra: Examining the Department of Energy's Loan Guarantee Program Hilary Kao Repository Citation Hilary Kao, Beyond Solyndra: Examining the Department of Energy's Loan Guarantee Program, 37 Wm. & Mary Envtl. L. & Pol'y Rev. 425 (2013), http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr/vol37/iss2/4 Copyright c 2013 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr BEYOND SOLYNDRA: EXAMINING THE DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY’S LOAN GUARANTEE PROGRAM HILARY KAO* ABSTRACT In the year following the Fukushima nuclear disaster in March 2011, the renewable and clean energy industries faced significant turmoil— from natural disasters, to political maelstroms, from the Great Recession, to U.S. debt ceiling debates. The Department of Energy’s Loan Guarantee Program (“DOE LGP”), often a target since before it ever received a dollar of appropriations, has been both blamed and defended in the wake of the bankruptcy filing of Solyndra, a California-based solar panel manufac- turer, in September 2011, because of the $535 million loan guarantee made to it by the Department of Energy (“DOE”) in 2009.1 Critics have suggested political favoritism in loan guarantee awards and have questioned the government’s proper role in supporting renewable energy companies and the renewable energy industry generally.2 This Article looks beyond the Solyndra controversy to examine the origin, structure and purpose of the DOE LGP. It asserts that loan guaran- tees can serve as viable policy tools, but require careful crafting to have the potential to be effective programs. -

Cadmium Telluride Photovoltaics - Wikipedia 1 of 13

Cadmium telluride photovoltaics - Wikipedia 1 of 13 Cadmium telluride photovoltaics Cadmium telluride (CdTe) photovoltaics describes a photovoltaic (PV) technology that is based on the use of cadmium telluride, a thin semiconductor layer designed to absorb and convert sunlight into electricity.[1] Cadmium telluride PV is the only thin film technology with lower costs than conventional solar cells made of crystalline silicon in multi-kilowatt systems.[1][2][3] On a lifecycle basis, CdTe PV has the smallest carbon footprint, lowest water use and shortest energy payback time of any current photo voltaic technology. PV array made of cadmium telluride (CdTe) solar [4][5][6] CdTe's energy payback time of less than a year panels allows for faster carbon reductions without short- term energy deficits. The toxicity of cadmium is an environmental concern mitigated by the recycling of CdTe modules at the end of their life time,[7] though there are still uncertainties[8][9] and the public opinion is skeptical towards this technology.[10][11] The usage of rare materials may also become a limiting factor to the industrial scalability of CdTe technology in the mid-term future. The abundance of tellurium—of which telluride is the anionic form— is comparable to that of platinum in the earth's crust and contributes significantly to the module's cost.[12] CdTe photovoltaics are used in some of the world's largest photovoltaic power stations, such as the Topaz Solar Farm. With a share of 5.1% of worldwide PV production, CdTe technology accounted for more than half of the thin film market in 2013.[13] A prominent manufacturer of CdTe thin film technology is the company First Solar, based in Tempe, Arizona. -

AS You Sow on Creating Greener Solar PV Panels

AS You Sow on Creating Greener Solar PV Panels Andrew Burger. March 28, 2012 Advocating solar PV manufacturers adopt a set of industry best practices, a new survey and report highlights the environmental benefits of using solar photovoltaic (PV) energy as compared to fossil fuels, while at the same time criticizing ongoing, outsized government support for fossil fuel production. “Even though there are toxic compounds used in the manufacturing of many solar panels, the generation of electricity from solar energy is much safer to both the environment and workers than production of electricity from coal, natural gas, or nuclear,” stated Amy Galland, PhD and research director at non-profit group As You Sow. “For example, once a solar panel is installed, it generates electricity with no emissions of any kind for decades, whereas coal-fired power plants in the U.S. emitted nearly two billion tons of carbon dioxide and millions of tons of toxic compounds in 2010 alone.” Based on an international survey of more than 100 solar PV manufac- turers, the best practices in As You Sow’s report, “Clean & Green: Best Practices in Photovoltaics” aim to protect the employee and community health and safety, as well as the broader environment. Also analyzed are investor considerations regarding environmental, social and govern- ance for responsible management of solar PV manufacturing business- es. The best practices listed were determined in consultation with sci- entists, engineers, academics, government labs and industry consult- ants. Solar PV CSR survey and report card “We have been working with solar companies to study and minimize the environmental health and safety risks in the production of solar panels and the industry has embraced the opportunities,” Vasilis Fthenakis, PhD and director of the National PV Environmen- tal Health and Safety Research Center at Brookhaven National Laboratory and director of the Center for Life Cycle Analysis at Columbia University, explained. -

Working on Climate: How Union Labor Can Power a Green Future

ISSUE BRIEF • SEPTEMBER 2019 Working on Climate: How Union Labor Can Power A Green Future The United States is one of the biggest contributors of climate change-inducing fossil fuel emissions.1 Scientists warn that continued reliance on fossil fuels will warm the planet.2 If we exceed the 1.5 degree Celsius warming threshold, increased temperatures could cause irreversibly destructive climate change, potentially making parts of the planet uninhabitable this century.3 Climate change has a disproportionate impact on renewable energy is necessary to stave off the worsening communities of color and vulnerable populations.4 If effects of this climate catastrophe.6 The IPCC report we keep emitting climate pollutants from fossil fuel warns that rapid warming would bring increasing facilities, marginalized communities will bear the droughts, wildfires, food shortages, coral reef die- biggest brunt. According to a 2018 report from the offs and other ecological and humanitarian crises by United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate 2040 — far earlier than expected.7 But greenhouse gas Change (IPCC), a warming climate “would dispropor- emissions such as carbon dioxide could be drastically tionately affect disadvantaged and vulnerable popula- reduced if we implement a “strategic shift” away from tions through food insecurity, higher food prices, fossil fuels and rely on renewable power for energy income losses, lost livelihood opportunities, adverse generation, accompanied by increased use of energy health impacts and population displacements.”5 efficiency technologies in buildings.8 Instead of doubling down on new fossil fuel facilities, Technology for a large-scale transition to renewables the United States must massively invest in clean energy. -

Laying the Foundation for a Bright Future: Assessing Progress

Laying the Foundation for a Bright Future Assessing Progress Under Phase 1 of India’s National Solar Mission Interim Report: April 2012 Prepared by Council on Energy, Environment and Water Natural Resources Defense Council Supported in part by: ABOUT THIS REPORT About Council on Energy, Environment and Water The Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) is an independent nonprofit policy research institution that works to promote dialogue and common understanding on energy, environment, and water issues in India and elsewhere through high-quality research, partnerships with public and private institutions and engagement with and outreach to the wider public. (http://ceew.in). About Natural Resources Defense Council The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) is an international nonprofit environmental organization with more than 1.3 million members and online activists. Since 1970, our lawyers, scientists, and other environmental specialists have worked to protect the world’s natural resources, public health, and the environment. NRDC has offices in New York City; Washington, D.C.; Los Angeles; San Francisco; Chicago; Livingston and Beijing. (www.nrdc.org). Authors and Investigators CEEW team: Arunabha Ghosh, Rajeev Palakshappa, Sanyukta Raje, Ankita Lamboria NRDC team: Anjali Jaiswal, Vignesh Gowrishankar, Meredith Connolly, Bhaskar Deol, Sameer Kwatra, Amrita Batra, Neha Mathew Neither CEEW nor NRDC has commercial interests in India’s National Solar Mission, nor has either organization received any funding from any commercial or governmental institution for this project. Acknowledgments The authors of this report thank government officials from India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), NTPC Vidyut Vyapar Nigam (NVVN), and other Government of India agencies, as well as United States government officials. -

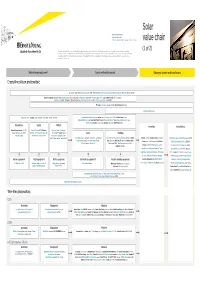

Lsoar Value Chain Value Chain

Solar Private companies in black Public companies in blue Followed by the founding date of companies less than 15 years old value chain (1 of 2) This value chain publication contains information gathered and summarized mainly from Lux Research and a variety of other public sources that we believe to be accurate at the time of ppggyublication. The information is for general guidance only and not intended to be a substitute for detailed research or the exercise of professional judgment. Neither EYGM Limited nor any other member of the global Ernst & Young organization nor Lux Research can accept responsibility for loss to any person relying on this publication. Materials and equipment Components and products Balance of system and installations Crystalline silicon photovoltaic GCL Silicon, China (2006); LDK Solar, China (2005); MEMC, US; Renewable Energy Corporation ASA, Norway; SolarWorld AG, Germany (1998) Bosch Solar Energy, Germany (2000); Canadian Solar, Canada/China (2001); Jinko Solar, China (2006); Kyocera, Japan; Sanyo, Japan; SCHOTT Solar, Germany (2002); Solarfun, China (2004); Tianwei New Energy Holdings Co., China; Trina Solar, China (1997); Yingli Green Energy, China (1998); BP Solar, US; Conergy, Germany (1998); Eging Photovoltaic, China SOLON, Germany (1997) Daqo Group, China; M. Setek, Japan; ReneSola, China (2003); Wacker, Germany Hyundai Heavy Industries,,; Korea; Isofoton,,p Spain ; JA Solar, China (();2005); LG Solar Power,,; Korea; Mitsubishi Electric, Japan; Moser Baer Photo Voltaic, India (2005); Motech, Taiwan; Samsung -

Tesla, Inc. Form 10-K Annual Report Filed 2017-03-01

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 10-K Annual report pursuant to section 13 and 15(d) Filing Date: 2017-03-01 | Period of Report: 2016-12-31 SEC Accession No. 0001564590-17-003118 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER Tesla, Inc. Mailing Address Business Address 3500 DEER CREEK RD 3500 DEER CREEK RD CIK:1318605| IRS No.: 912197729 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 1231 PALO ALTO CA 94070 PALO ALTO CA 94070 Type: 10-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-34756 | Film No.: 17655025 650-681-5000 SIC: 3711 Motor vehicles & passenger car bodies Copyright © 2017 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2016 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 001-34756 Tesla, Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 91-2197729 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 3500 Deer Creek Road Palo Alto, California 94304 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (650) 681-5000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, $0.001 par value The NASDAQ Stock Market LLC Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

Bankrupt Companies

The List of Fallen Solar Companies: 2015 to 2009: S.No Year/Status Company Name and Details 118 2015 Enecsys (microinverters) bankrupt -- Enecsys raised more than $55 million in VC from investors including Wellington Partners, NES Partners, Good Energies and Climate Change Capital Private Equity for its microinverter technology. 117 2015 QBotix (trackers) closed -- QBotix had a two-axis solar tracker system where the motors, instead of being installed two per tracker, were moved around by a rail-mounted robot that adjusted each tracker every 40 minutes. But while QBotix was trying to gain traction, single-axis solar trackers were also evolving and driving down cost. QBotix raised more than $19.5 million from Firelake, NEA, DFJ JAIC, Siemens Ventures, E.ON and Iberdrola. 116 2015 Solar-Fabrik (c-Si) bankrupt -- German module builder 115 2015 Soitec (CPV) closed -- France's Soitec, one of the last companies with a hope of commercializing concentrating photovoltaic technology, abandoned its solar business. Soitec had approximately 75 megawatts' worth of CPV projects in the ground. 114 2015 TSMC (CIGS) closed -- TSMC Solar ceased manufacturing operations, as "TSMC believes that its solar business is no longer economically sustainable." Last year, TSMC Solar posted a champion module efficiency of 15.7 percent with its Stion- licensed technology. 113 2015 Abengoa -- Seeking bankruptcy protection 112 2014 Bankrupt, Areva's solar business (CSP) closed -- Suffering through a closed Fukushima-inspired slowdown in reactor sales, Ausra 111 2014 Bankrupt, -

Wind Power Today

Contents BUILDING A NEW ENERGY FUTURE .................................. 1 BOOSTING U.S. MANUFACTURING ................................... 5 ADVANCING LARGE WIND TURBINE TECHNOLOGY ........... 7 GROWING THE MARKET FOR DISTRIBUTED WIND .......... 12 ENHANCING WIND INTEGRATION ................................... 14 INCREASING WIND ENERGY DEPLOYMENT .................... 17 ENSURING LONG-TERM INDUSTRY GROWTH ................. 21 ii BUILDING A NEW ENERGY FUTURE We will harness the sun and the winds and the soil to fuel our cars and run our factories. — President Barack Obama, Inaugural Address, January 20, 2009 n 2008, wind energy enjoyed another record-breaking year of industry growth. By installing 8,358 megawatts (MW) of new Wind Energy Program Mission: The mission of DOE’s Wind Igeneration during the year, the U.S. wind energy industry took and Hydropower Technologies Program is to increase the the lead in global installed wind energy capacity with a total of development and deployment of reliable, affordable, and 25,170 MW. According to initial estimates, the new wind projects environmentally responsible wind and water power completed in 2008 account for about 40% of all new U.S. power- technologies in order to realize the benefits of domestic producing capacity added last year. The wind energy industry’s renewable energy production. rapid expansion in 2008 demonstrates the potential for wind energy to play a major role in supplying our nation with clean, inexhaustible, domestically produced energy while bolstering our nation’s economy. Protecting the Environment To explore the possibilities of increasing wind’s role in our national Achieving 20% wind by 2030 would also provide significant energy mix, government and industry representatives formed a environmental benefits in the form of avoided greenhouse gas collaborative to evaluate a scenario in which wind energy supplies emissions and water savings. -

Climate Law and Policy in North America: Prospects for Regionalism†

CRAIK-DIMENTO[1] (DO NOT DELETE) 2/5/2016 12:39 PM Climate Law and Policy in North America: Prospects for Regionalism† NEIL CRAIK* JOSEPH F.C. DIMENTO** TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 196 II. CONTEXT: MULTI-LEVEL AND MULTI-TRACK CLIMATE-CHANGE GOVERNANCE ...................................................................... 197 III. THE EXISTING GOVERNANCE LANDSCAPE: CLIMATE CHANGE COMMITMENTS AND POLICIES .............................................................. 202 A. North American GHG Emissions ............................................................. 202 B. International Commitments and Programs .............................................. 205 C. Domestic Policies .................................................................................... 213 † This paper was originally presented at the IUCN Academy of Environmental Law Conference on Climate Law in Developing Countries Post 2012: North and South Perspectives held in Ottawa, Canada on September 26-28, 2008. The paper was also presented at a Research Workshop on Regional Climate Change Governance in North America held at the Tecnologico de Monterrey in Mexico City on January 19-20, 2009. The authors are grateful to the participants of these events for the discussion of ideas related to the paper. The writing of the paper was supported by grants from the Harrison McCain Foundation, The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and the Department of