The Sacrament of Unity Intercommunion and Some Forgotten Truths

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

File Downloadenglish

CURIA PRIEPOSITI GENERALIS Cur. Gen. 89/8 Jesuit Life SOCIETATIS IESU in the Spirit ROMA · Borgo S. Spirito, 5 TO THE WHOLE SOCIETY Dear Fathers and Brothers, P.C. Introduction With this letter I wish to react to numerous letters which have come to me on Life in the Spirit in the Society today. Prepared in great part with the help of a community meeting or a consultation, these letters witness to the spiritual health of the apostolic body of the Society. And they express the desire to experience a new spiritual vigor, especially with the approach of the Ignatian Year. They do not hide, though, the difficulties common to every life in the Spirit today. Such a life feels at one and the same time the effects of the strong need to live spiritually which so many of our contemporaries experience, of a whole culture in the throes of losing its taste for God, of the mentality fashioned by the currents of our times, and of the search for dubious mysticisms. The letters do not speak of life in the Spirit as if it were a reality only during moments of escape or times of rest. They are faithful to the contemplation on the Incarnation (Sp. Ex. 102 ff.) in expressing the bond which St. Ignatius considered indis pensable for every life in the Spirit: "the greater glory of God and the service of men" (Form. Inst. n.l). "In order to reach this state of contemplation, St. Ignatius demands of you that you be men of prayer," the Holy Father reminded us recently, "in order to be also teachers of prayer; at the same time he expects you to be men of mortification, in order to be visible signs of Gospel values" (John Paul II, Homily, September 2, 1983, at GC 33). -

Implementing Summorum Pontificum in the Diocese of Davenport

DIOCESE OF DAVENPORT Policies for Implementing Summorum Pontificum in the Diocese of Davenport These pages may be reproduced by parish and Diocesan staff for their use Policy promulgated at the Pastoral Center of the Diocese of Davenport–effective September 14, 2007 Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross Revised November 27, 2011 Revised October 15, 2012 Most Reverend Martin Amos Bishop of Davenport TABLE OF CONTENTS §IV-249 POLICIES FOR IMPLEMENTING SUMMORUM PONTIFICUM IN THE DIOCESE OF DAVENPORT: INTRODUCTION 1 §IV-249.1 THE ROLE OF THE BISHOP 2 §IV-249.2 FACULTIES 3 §IV-249.3 REQUIREMENTS FOR THE CELEBRATION OF MASS 4 §IV-249.4 REQUIREMENTS FOR THE CELEBRATION OF THE OTHER SACRAMENTS AND RITES 6 §IV-249.5 REPORTING REQUIREMENTS 6 APPENDICES Appendix A: Documentation Form 7 Appendix B: Resources 8 0 §IV-249 Policies for Implementing Summorum Pontificum in the Diocese of Davenport §IV-249 POLICIES IMPLEMENTING SUMMORUM PONTIFICUM IN THE DIOCESE OF DAVENPORT Introduction In the 1980s, Pope John Paul II established a way to allow priests with special permission to celebrate Mass and the other sacraments using the rites that were in use before Vatican II (the 1962 Missal, also called the Missal of John XXIII or the Tridentine Mass). Effective September 14, 2007, Pope Benedict XVI loosened the restrictions on the use of the 1962 Missal, such that the special permission of the bishop is no longer required. This action was taken because, as universal shepherd, His Holiness has a heart for the unity of the Church, and sees the option of allowing a more generous use of the Mass of 1962 as a way to foster that unity and heal any breaches that may have occurred after Vatican II. -

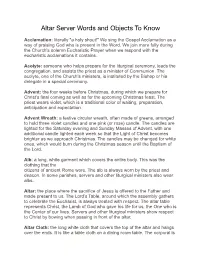

Altar Server Words and Objects to Know

Altar Server Words and Objects To Know Acclamation: literally "a holy shout!" We sing the Gospel Acclamation as a way of praising God who is present in the Word. We join more fully during the Church's solemn Eucharistic Prayer when we respond with the eucharistic acclamations it contains. Acolyte: someone who helps prepare for the liturgical ceremony, leads the congregation, and assists the priest as a minister of Communion. The acolyte, one of the Church's ministers, is instituted by the Bishop or his delegate in a special ceremony. Advent: the four weeks before Christmas, during which we prepare for Christ's final coming as well as for the upcoming Christmas feast. The priest wears violet, which is a traditional color of waiting, preparation, anticipation and expectation. Advent Wreath: a festive circular wreath, often made of greens, arranged to hold three violet candles and one pink (or rose) candle. The candles are lighted for the Saturday evening and Sunday Masses of Advent, with one additional candle lighted each week so that the Light of Christ becomes brighter as we approach Christmas. The candles may be changed for white ones, which would burn during the Christmas season until the Baptism of the Lord. Alb: a long, white garment which covers the entire body. This was the clothing that the citizens of ancient Rome wore. The alb is always worn by the priest and deacon. In some parishes, servers and other liturgical ministers also wear albs. Altar: the place where the sacrifice of Jesus is offered to the Father and made present to us. -

Tridentine Community News July 26, 2009

Tridentine Community News July 26, 2009 In Defense of Individual Celebration of the Holy Mass side altars lining the walls of its chapel. Older churches such as our own were constructed with side altars for the same reason, to The 1983 Code of Canon Law urges priests to celebrate the Holy allow the assisting priests in residence at the parish to offer their Sacrifice of the Mass every day. Canon 276 §2 n. 2 states: own Masses each day. In an interesting sign of the times, at the “…priests are earnestly invited to offer the eucharistic sacrifice Fraternity of St. Peter’s seminary in Nebraska, priests celebrate daily…”. (Key point: It is not mandatory.) their individual Masses in a room cluttered with mismatched side altars salvaged from various churches. Priests living in a religious community, such as at a monastery, often have a regularly scheduled daily Mass. If they follow the A little-known fact is that there is one time that a priest may Ordinary Form, this Community Mass can be one in which some concelebrate at a or all of the priests concelebrate the Mass. Tridentine Mass, and that is at a If the religious community, or an individual priest, follows the Mass of Extraordinary Form, concelebration is not permitted. Each priest Ordination. Each must celebrate his own individual Mass. The below historic photo ordinand shows priests celebrating private Masses at Orchard Lake’s Ss. concelebrates the Cyril & Methodius Seminary, pre-Vatican II. Mass with the bishop. Each new priest is assisted by an experienced priest at his side, as pictured in the adjacent photo from an Institute of Christ the King ordination. -

Jesuits and Eucharistic Concelebration

JesuitsJesuits and Eucharistic Concelebration James J. Conn, S.J.S.J. Jesuits,Jesuits, the Ministerial PPriesthood,riesthood, anandd EucharisticEucharistic CConcelebrationoncelebration JohnJohn F. Baldovin,Baldovin, S.J.S.J. 51/151/1 SPRING 2019 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits is a publication of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States. The Seminar on Jesuit Spirituality is composed of Jesuits appointed from their provinces. The seminar identifies and studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially US and Canadian Jesuits, and gath- ers current scholarly studies pertaining to the history and ministries of Jesuits throughout the world. It then disseminates the results through this journal. The opinions expressed in Studies are those of the individual authors. The subjects treated in Studies may be of interest also to Jesuits of other regions and to other religious, clergy, and laity. All who find this journal helpful are welcome to access previous issues at: [email protected]/jesuits. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR Note: Parentheses designate year of entry as a seminar member. Casey C. Beaumier, SJ, is director of the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. (2016) Brian B. Frain, SJ, is Assistant Professor of Education and Director of the St. Thomas More Center for the Study of Catholic Thought and Culture at Rock- hurst University in Kansas City, Missouri. (2018) Barton T. Geger, SJ, is chair of the seminar and editor of Studies; he is a research scholar at the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies and assistant professor of the practice at the School of Theology and Ministry at Boston College. -

LECTIONARY Sundays and Solemnities

THE ROMAN MISSAL Revised by decree of the Second Vatican Council and published by authority of Pope Paul VI LECTIONARY Sundays and Solemnities Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops Ottawa – Canada 1992 LECTIONARY Sundays and Solemnities Approved by the National Liturgical Office for use in Canada Imprimatur: Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, Ottawa, October 16, 1991. This edition of the Lectionary is based on O rdo Lectionum Missae, editio typica altera, Ty p i s Polyglottis Vaticanus 1981. The Scripture quotations contained herein are adapted from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyrighted, 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America, and are used by permission. All rights reserved. The English translation of the decrees and the General Introduction, the psalm responses, the alleluia and gospel acclamations and verses, the titles, introduction and conclusion of the readings from the L e c t i o n ay r for Mass (Second Typical Edition) © 1969, 1980, 1981, 1992, International Committee on English in the Liturgy, Inc. All rights reserved. Sequence for Easter and Pentecost, copyright © Peter J. Scagnelli. All rights reserved. Lectionary, Sundays and Solemnities,copyright © Concacan Inc., 1992. All rights reserved. Edited by Published by National Liturgical Office Publications Service Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops 90 Parent Avenue Ottawa, Canada K1N 7B1 ISBN 0-88997-269-9 Legal Deposit: National Library, Ottawa, Canada Printed -

Concelebration with Agafangel

■ Yet more historic pages in the chronicle of the Orthodox Resistance Greek and Russian Anti-Ecumenists Embrace in Concelebration An historic visit lory to God for all things! The Holy Synod in Resistance had the especial blessing of welcoming His Eminence, Bishop Agafangel ofG Odessa and Tauris to its Headquarters, that is, to the Holy Monastery of Sts. Cyprian and Justina, in Phyle, Attica, offering him hospitality thereat from November 15 to November 20, 2007 (Old Style). ■ Our momentous and multilevel interaction with His Eminence, Bishop Agafangel took on the nature of a truly historic visit, in view of the fact that this blessed Hierarch already heads that large segment of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA) which not only has not accepted the false union, this past May, between the ROCA and the Moscow Patriarchate, but which is fully conscious that it constitutes the continuation of the original Rus- sian Orthodox Church Abroad, since it continues to preserve the latter’s Historical Heritage. * * * On Wednesday, November 15, around 7:00 p.m., our Holy Synod welcomed His Eminence, Bishop Agafangel with gladness and rejoicing to its Synodal Headquarters. At the conclusion of the Doxology service in the Monastery’s new Cathedral, His Grace, Bishop Cyprian of Oreoi, Acting President of the Holy Synod, addressed His Eminence, conveying to him welcoming wishes from our ailing and much-revered First Hierarch, Metropolitan Cyprian, and also from the oth- er members of our Hierarchy. “In your person,” said His Grace, the Act- ing President, “we behold Holy Russia, from the times of St. -

Materialien Für Das Projekt: Syrische Anaphoren

Materialien fur¨ das Projekt: Syrische Anaphoren Thomas Klampfl 5.12.2008 Brock, S., Syriac Studies. A Classified Bibliography (1960–1990), Kaslik (Li- ban) 1996. Enth¨alt folgende Bibliographien: Brock, S., Syriac Studies. A Classified Bibliography (1960–1970), in: Parole de l’Orient 4 (1973) 393–465. Brock, S., Syriac Studies. A Classified Bibliography (1971–1980), in: Parole de l’Orient 10 (1981/82) 291–412. Brock, S., Syriac Studies. A Classified Bibliography (1981–1985), in: Parole de l’Orient 14 (1987) 289–360. Brock, S., Syriac Studies. A Classified Bibliography (1986–1990), in: Parole de l’Orient 17 (1992) 211–301. → Manuscripts → Catalogues and descriptions of manuscripts (209– 212): Allen, N., Syriac fragments in the Wellcome Institute Library, in: JRAS 1987, 43–7. Assfalg, J., Verzeichnis der orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland. 5. Syrische Handschriften, Wiesbaden 1963. Berkers, J.N., Catalogue des manuscrits du fond patriarcal de Rahmani con- serv´es `aCharfet, contenant des Anaphores, in: POC 12 (1962) 224–42. Bernheimer, C., Catalogo dei manoscritti orientali della Bibliotheca Estense, Rome 1960. Brock, S.P., The Syriac manuscripts in the National Library, Athens, in: LM 79 (1966) 165–84. Brock, S.P., Two Syriac manuscripts in the Library of Selwyn College, Cam- bridge, in: OC 55 (1971) 149–60. Brock, S.P., Catalogue des manuscrits du Centre Franciscain d’´etudes orien- tales chr´etiennes, Le Caire. 1. Syriac Manuscripts, in: SOCC 18 (1985) 213–8. Brock, S.P., Syriac manuscripts copied on the Black Mountain, near Antioch, in: Festgabe J. Assfalg, 59–67. Cecchelli, C. / Furlani, G. / Salmi, M., The Rabbula Gospel. -

Concelebration Card, Eucharistic Prayer II

EucHARISTIC PRAYER II For Concelebration • The parts for all concelebrants are to be recited in a low voice and in such a way that the voice of the principal celebrant is clearly heard by the people. (See General Instruction of the Roman Missal, no. 218.) The principal celebrant, with hands extended, says: After this, the principal celebrant and all concelebrants continue: 'W" ou are indeed Holy, 0 Lord, In a similar way, when supper was ended, ll the fount of all holiness. he took the chalice and, once more giving thanks, The principal celebrant and all concelebrants, holding their he gave it to his disciples, saying: hands extended toward the offerings, say: Make holy, therefore, these gifts, we pray, Each concelebrant extends his right hand toward the by sending down your Spirit upon them chalice, if this seems appropriate. like the dewfall, TAKE THIS, ALL OF YOU, AND DRINK FROM IT, FOR THIS IS THE CHALICE OF MY BLOOD, The principal celebrant joins his hands and makes the THEBLOODOFTHENEWANDETERNALCOVENANT, Sign of the Cross once over the bread and the chalice together, saying: WHICH WILL BE POURED OUT FOR YOU AND so that they may become for us FOR MANY the Body and ~ Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ. FOR THE FORGIVENESS OF SINS. Do THIS IN MEMORY OF ME. They join their hands. At the time he was betrayed The concelebrants join their hands, look toward the chalice and entered willingly into his Passion, as it is shown, and after this bow profoundly. he took bread and, giving thanks, broke it, and gave it to his disciples, saying: Then the principal celebrant says: The mystery of faith. -

Some Notes on the Bema in the East and West Syrian Traditions

VII Some Notes on the Bema etc. 327 I,. Bouyer even goes so far as to claim that what is now generally accepted as the " Syrian arrangement " was formerly that of the ~~zantikerite as well ('). Because of the importance of this quesfion for the history of worship, it might be profitable to re- view the archeological and liturgical evidence. Some Notes on the Bema The most common solution to the problem of church anange- ment in both East and West was to place the seats for the clergy in the East and West Syrian Traditions in an apse at one end - usually the east - of the church. Before the clergy, at the beginning of the nave (or in the transept, or in the apse itself, depending on the architecture of the church) stood the altar. Beyond, further into the nave, stood the ambon Since the publication of H. C. Butler's Early Chwches of or ambons for the psalmody and readings. The congregation Syria (Princeton, 1929). archeologists and liturgiologists have occupied, it seems, not so much the central nave as today, but shown considerable interest in certain peculiarities in the liturgical the side naves, thus leaving the center of the church free for pro- disposition of a number of ancient churches in North Syria ('). cessions and other comings and goings of the ministers demanded by the various rites ('). (1) A partial list of recent works dealing with this problem would But modern archeological discoveries have shown that two include: H. C. BUTLER, Early Churches of Syria, Princeton. 1929,and Syria, areas of early Christianity followed a plan of their own: North Publications of the Princeton University Archeological Expedition to Syria Africa, and parts of Northern Syria and Mesopotamia. -

Robert Taft Ex Oriente Lux? Some Reflections on Eucharistic Concelebration

Robert Taft Ex Oriente Lux? Some Reflections on Eucharistic Concelebration The following notes on concelebration do not pretend to offer a complete study of the Eastern tradition, nor definitive solutions to the growing dissatisfaction with the restored roman rite of Eucharistic concelebration. But they may help to clarify the status quaestionis, rectify misinterpretations of early Eucharistic discipline, and dispel misconceptions concerning the antiquity and normative value of Eastern usage. It has long been a theological device to turn eastwards in search of supporting liturgical evidence for what one has already decided to do anyway. Something like this was at work in certain pre-Vatican II discussion on the possibility of restoring concelebration in the Roman rite. The underlying presupposition seems to be that Eastern practice will reflect a more ancient- indeed the ancient - tradition of thee undivided Church. 1. Concelebration in the Christian East Today The information on contemporary Eastern forms of Eucharistic concelebration given by McGowan and King is generally accurate, with a few exceptions that will be corrected here. The Armenians practice Eucharistic concelebration only at Episcopal and presbyteral ordinations, a custom they may have borrowed from the Latins. The Maronites, also influenced by the Latins, probably owe their practice of verbal co-consecration to scholastic theology of the (P.81) Eucharist, Before the seventeenth century, concelebration without co-consecration was in use. In the Coptic Orthodox Church several presbyters participate in the common Eucharist vested, in the sanctuary. Only the main celebrant (who is not the presiding celebrant if a bishop is present) stands at the altar, but the prayers are shared among the several priests. -

The Sacramentary

211111111111112 The Sacramentary Volume Two Part 2 211111111111112 EUCHARISTIC PRAYERS I-IV Let us give thanks to the Lord our God PREFACE DIALOGUE EUCHARISTIC PRAYER I (THE ROMAN CANON) The priest leads the assembly in the eucharistic prayer. The people take part reverently and attentively and make the acclamations. The eucharistic prayer may be sung (see page 821). The priest begins the eucharistic prayer. Extending his hands, he sings or says: & œœœœœ˙ The Lord be with you. The people answer: & œœœ œ ˙ And al - so with you. He lifts up his hands and continues: & œ- œ œ œ œ ˙ Lift up your hearts. The people answer: & œœ œ œœ œ ˙ We lift them up to the Lord. With hands outstreched, he continues: & œ œ œ œœœ œ œ œ ˙ Let us give thanks to the Lord our God. The people answer: & œœ œœœ œ œ œ œ˙˙ It is right to give thanks and praise. 702 THE ORDER OF MASS The priest continues the preface with hands outstretched. Alternative openings for the prefaces may be found on pages 508–509. At the end of the preface, the priest joins his hands and, together with the people, sings or says: & ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ œ œ œœœœ œ ˙ œ œ œœœ Ho - ly, ho - ly, ho- ly Lord, God of power and might, heav- en and earth are & œ œœ œ˙ œ œ œœœ ˙ ˙ œ œ œœ œ full of your glo - ry. Ho - san - na in the high - est. Bless - ed is he who & œœœ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œœœ ˙ ˙ comes in the name of the Lord.