Jesuits and Eucharistic Concelebration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE EPISTLE St

THE EPISTLE St. Philip’s Episcopal Church 342 East Wood Street Palatine, Illinois 60067-5357 (847) 358-0615 www.stphilipspalatine.org http://www.facebook.com/stphilipspalatine The Rev. Jim Stanley, Rector Dear friend in Christ, What does your faith in Jesus mean to you? Has your Christian faith seen you through some tough times? Does the knowledge that you are "sealed by the Holy Spirit in Baptism and marked as Christ's own forever" (BCP p. 308) bring you hope and comfort for your future? Have there been times when a particular passage of Scripture has lifted you? I'm sure most people reading this know exactly what I mean. I don't want us to simply stop with being grateful for our faith. Be thankful, yes; but the same Lord who has so comforted and encouraged us, has also urged us to serve others. Jesus expects us to work for justice and peace. We are to feed the hungry, advocate for the poor, comfort the widow and orphan. May we never lose sight of this Great Commandment to do to others as we would have done to ourselves! In addition to leaving us with a Great Commandment, our Lord also assigned us a Great Commission. Just before He ascended to His Father in Heaven, Jesus told His disciples -- 1 and by extension, all who would come to believe in Him in the future -- to "Go into all the world and proclaim His Good News, making disciples of all nations and baptizing in the Name of the Holy Trinity." Jesus ordered that His message be taken "to the uttermost parts of the earth". -

The Rites of Holy Week

THE RITES OF HOLY WEEK • CEREMONIES • PREPARATIONS • MUSIC • COMMENTARY By FREDERICK R. McMANUS Priest of the Archdiocese of Boston 1956 SAINT ANTHONY GUILD PRESS PATERSON, NEW JERSEY Copyright, 1956, by Frederick R. McManus Nihil obstat ALFRED R. JULIEN, J.C. D. Censor Lib1·or111n Imprimatur t RICHARD J. CUSHING A1·chbishop of Boston Boston, February 16, 1956 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA INTRODUCTION ANCTITY is the purpose of the "new Holy Week." The news S accounts have been concerned with the radical changes, the upset of traditional practices, and the technical details of the re stored Holy Week services, but the real issue in the reform is the development of true holiness in the members of Christ's Church. This is the expectation of Pope Pius XII, as expressed personally by him. It is insisted upon repeatedly in the official language of the new laws - the goal is simple: that the faithful may take part in the most sacred week of the year "more easily, more devoutly, and more fruitfully." Certainly the changes now commanded ,by the Apostolic See are extraordinary, particularly since they come after nearly four centuries of little liturgical development. This is especially true of the different times set for the principal services. On Holy Thursday the solemn evening Mass now becomes a clearer and more evident memorial of the Last Supper of the Lord on the night before He suffered. On Good Friday, when Holy Mass is not offered, the liturgical service is placed at three o'clock in the afternoon, or later, since three o'clock is the "ninth hour" of the Gospel accounts of our Lord's Crucifixion. -

Saint Patrick Parish ‘A Faith Community Since 1870‘ 1 Cross Street Whitinsville, MA 01588

Saint Patrick Parish ‘A Faith Community since 1870‘ 1 Cross Street Whitinsville, MA 01588 MASS SCHEDULE Office Hours: Monday-Friday 9:00 AM - 4:00 PM Saturday: 4:30 PM Sunday 8:00 AM, 10:00 AM, 5:00 PM Rectory Phone: 508-234-5656 Monday– Wednesday 8:30 AM Rectory Fax: 508-234-6845 Religious Ed. Phone: 508-234-3511 Sacrament of Reconciliation: Parish Website: www.mystpatricks.com Confessions are offered every Saturday from 3:30 - 4:00 PM in the Church or by calling the Find us on Facebook at Parish Office for an appointment. St Patricks Parish Whitinsville St. Patrick Church, Whitinsville MA October 16, 2016 Twenty-Ninth Sunday in Ordinary Time Rev. Tomasz Borkowski: Deacon Patrick Stewart: Deacon Chris Finan: Deacon Pastor Deacon [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Mrs. Christina Pichette: Mrs. Shelly Mombourquette: Pastoral Associate to Youth Ministry Administrative Assistant [email protected] [email protected] Mrs. Maryanne Swartz: Mrs. Mary Contino: Wedding Coordinator Coordinator of Children’s Ministries [email protected] [email protected] Mrs. Jackie Trottier: Operations Manager Mr. Jack Jackson: Cemetery Superintendent: [email protected] [email protected] Ms. Jeanne LeBlanc: Ministry Scheduler Mrs. Marylin Arrigan: Staff Support, Bulletin [email protected] [email protected] RELIGIOUS EDUCATION SCHEDULE OUR LADY OF THE VALLEY REGIONAL SCHOOL Pre school Sunday 10:00 AM - 11:00 AM 71 Mendon Street, Uxbridge, MA 01569 Kindergarten Sunday 10:00 AM - 11:00 AM 508-278-5851 First Grade Sunday 10:00 AM - 11:00 AM www.ourladyofthevalleyregional.com Grades 2 & 3 Sunday 11:20 AM - 12:20 PM Grades 4 & 5 Sunday 8:50 AM - 9:50 AM Free Breakfast every Saturday from 8-10 Children are to attend the 10:00 am Mass and take part AM for those in need. -

File Downloadenglish

CURIA PRIEPOSITI GENERALIS Cur. Gen. 89/8 Jesuit Life SOCIETATIS IESU in the Spirit ROMA · Borgo S. Spirito, 5 TO THE WHOLE SOCIETY Dear Fathers and Brothers, P.C. Introduction With this letter I wish to react to numerous letters which have come to me on Life in the Spirit in the Society today. Prepared in great part with the help of a community meeting or a consultation, these letters witness to the spiritual health of the apostolic body of the Society. And they express the desire to experience a new spiritual vigor, especially with the approach of the Ignatian Year. They do not hide, though, the difficulties common to every life in the Spirit today. Such a life feels at one and the same time the effects of the strong need to live spiritually which so many of our contemporaries experience, of a whole culture in the throes of losing its taste for God, of the mentality fashioned by the currents of our times, and of the search for dubious mysticisms. The letters do not speak of life in the Spirit as if it were a reality only during moments of escape or times of rest. They are faithful to the contemplation on the Incarnation (Sp. Ex. 102 ff.) in expressing the bond which St. Ignatius considered indis pensable for every life in the Spirit: "the greater glory of God and the service of men" (Form. Inst. n.l). "In order to reach this state of contemplation, St. Ignatius demands of you that you be men of prayer," the Holy Father reminded us recently, "in order to be also teachers of prayer; at the same time he expects you to be men of mortification, in order to be visible signs of Gospel values" (John Paul II, Homily, September 2, 1983, at GC 33). -

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms Liturgical Objects Used in Church The chalice: The The paten: The vessel which golden “plate” that holds the wine holds the bread that that becomes the becomes the Sacred Precious Blood of Body of Christ. Christ. The ciborium: A The pyx: golden vessel A small, closing with a lid that is golden vessel that is used for the used to bring the distribution and Blessed Sacrament to reservation of those who cannot Hosts. come to the church. The purificator is The cruets hold the a small wine and the water rectangular cloth that are used at used for wiping Mass. the chalice. The lavabo towel, The lavabo and which the priest pitcher: used for dries his hands after washing the washing them during priest's hands. the Mass. The corporal is a square cloth placed The altar cloth: A on the altar beneath rectangular white the chalice and cloth that covers paten. It is folded so the altar for the as to catch any celebration of particles of the Host Mass. that may accidentally fall The altar A new Paschal candles: Mass candle is prepared must be and blessed every celebrated with year at the Easter natural candles Vigil. This light stands (more than 51% near the altar during bees wax), which the Easter Season signify the and near the presence of baptismal font Christ, our light. during the rest of the year. It may also stand near the casket during the funeral rites. The sanctuary lamp: Bells, rung during A candle, often red, the calling down that burns near the of the Holy Spirit tabernacle when the to consecrate the Blessed Sacrament is bread and wine present there. -

Implementing Summorum Pontificum in the Diocese of Davenport

DIOCESE OF DAVENPORT Policies for Implementing Summorum Pontificum in the Diocese of Davenport These pages may be reproduced by parish and Diocesan staff for their use Policy promulgated at the Pastoral Center of the Diocese of Davenport–effective September 14, 2007 Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross Revised November 27, 2011 Revised October 15, 2012 Most Reverend Martin Amos Bishop of Davenport TABLE OF CONTENTS §IV-249 POLICIES FOR IMPLEMENTING SUMMORUM PONTIFICUM IN THE DIOCESE OF DAVENPORT: INTRODUCTION 1 §IV-249.1 THE ROLE OF THE BISHOP 2 §IV-249.2 FACULTIES 3 §IV-249.3 REQUIREMENTS FOR THE CELEBRATION OF MASS 4 §IV-249.4 REQUIREMENTS FOR THE CELEBRATION OF THE OTHER SACRAMENTS AND RITES 6 §IV-249.5 REPORTING REQUIREMENTS 6 APPENDICES Appendix A: Documentation Form 7 Appendix B: Resources 8 0 §IV-249 Policies for Implementing Summorum Pontificum in the Diocese of Davenport §IV-249 POLICIES IMPLEMENTING SUMMORUM PONTIFICUM IN THE DIOCESE OF DAVENPORT Introduction In the 1980s, Pope John Paul II established a way to allow priests with special permission to celebrate Mass and the other sacraments using the rites that were in use before Vatican II (the 1962 Missal, also called the Missal of John XXIII or the Tridentine Mass). Effective September 14, 2007, Pope Benedict XVI loosened the restrictions on the use of the 1962 Missal, such that the special permission of the bishop is no longer required. This action was taken because, as universal shepherd, His Holiness has a heart for the unity of the Church, and sees the option of allowing a more generous use of the Mass of 1962 as a way to foster that unity and heal any breaches that may have occurred after Vatican II. -

Altar Server Words and Objects to Know

Altar Server Words and Objects To Know Acclamation: literally "a holy shout!" We sing the Gospel Acclamation as a way of praising God who is present in the Word. We join more fully during the Church's solemn Eucharistic Prayer when we respond with the eucharistic acclamations it contains. Acolyte: someone who helps prepare for the liturgical ceremony, leads the congregation, and assists the priest as a minister of Communion. The acolyte, one of the Church's ministers, is instituted by the Bishop or his delegate in a special ceremony. Advent: the four weeks before Christmas, during which we prepare for Christ's final coming as well as for the upcoming Christmas feast. The priest wears violet, which is a traditional color of waiting, preparation, anticipation and expectation. Advent Wreath: a festive circular wreath, often made of greens, arranged to hold three violet candles and one pink (or rose) candle. The candles are lighted for the Saturday evening and Sunday Masses of Advent, with one additional candle lighted each week so that the Light of Christ becomes brighter as we approach Christmas. The candles may be changed for white ones, which would burn during the Christmas season until the Baptism of the Lord. Alb: a long, white garment which covers the entire body. This was the clothing that the citizens of ancient Rome wore. The alb is always worn by the priest and deacon. In some parishes, servers and other liturgical ministers also wear albs. Altar: the place where the sacrifice of Jesus is offered to the Father and made present to us. -

Tridentine Community News July 26, 2009

Tridentine Community News July 26, 2009 In Defense of Individual Celebration of the Holy Mass side altars lining the walls of its chapel. Older churches such as our own were constructed with side altars for the same reason, to The 1983 Code of Canon Law urges priests to celebrate the Holy allow the assisting priests in residence at the parish to offer their Sacrifice of the Mass every day. Canon 276 §2 n. 2 states: own Masses each day. In an interesting sign of the times, at the “…priests are earnestly invited to offer the eucharistic sacrifice Fraternity of St. Peter’s seminary in Nebraska, priests celebrate daily…”. (Key point: It is not mandatory.) their individual Masses in a room cluttered with mismatched side altars salvaged from various churches. Priests living in a religious community, such as at a monastery, often have a regularly scheduled daily Mass. If they follow the A little-known fact is that there is one time that a priest may Ordinary Form, this Community Mass can be one in which some concelebrate at a or all of the priests concelebrate the Mass. Tridentine Mass, and that is at a If the religious community, or an individual priest, follows the Mass of Extraordinary Form, concelebration is not permitted. Each priest Ordination. Each must celebrate his own individual Mass. The below historic photo ordinand shows priests celebrating private Masses at Orchard Lake’s Ss. concelebrates the Cyril & Methodius Seminary, pre-Vatican II. Mass with the bishop. Each new priest is assisted by an experienced priest at his side, as pictured in the adjacent photo from an Institute of Christ the King ordination. -

Theological Basis and Canonical Implications of Involvement of Religious in the Local Church

1 Theological basis and Canonical Implications of Involvement of Religious in the Local Church 1. Introduction There are two states in the church – the clergy and the laity. The two groups of persons are referred to as hierarchical/institutional and charismatic/prophetic. There are different categories of people in the church – the clergy, the consecrated people and the laity. The three categories are to work in collaboration with each other in order to evangelise and build the Body of Christ. The consecrated persons/religious are in the vanguard of the mission of the church. They are encouraged to be enterprising in their initiatives and undertakings in keeping with the charismatic and prophetic nature of religious life. But they depend on the hierarchical/institutional church for discernment and approval of their charism and apostolate. Working together does cause some conflict and tensions. Hence a proper understanding of these two groups along with the theological basis of consecrated life, their roles and dependence (canonical implications), will help to clarify the relationships and bring about more effectiveness in ministry. If they work in partnership, with dialogue and mutual consultation, the church will benefit and the kingdom that Christ inaugurated will be furthered. 2. Brief History of Consecrated life How did consecrated life begin? What were its essentials? What is its present form? What was the role of the hierarchy in approving it? In order to seek an answer to these questions, we will have to look into a brief history of consecrated life. In early Christian communities there were virgins, widows and ascetics who lived a life distinguished from the ordinary life by its leaning to perfection, continence and sometimes the renunciation of riches. -

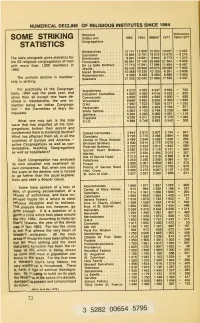

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

Traditional Latin Mass (TLM), Otherwise Known As the Extraordinary Form, Can Seem Confusing, Uncomfortable, and Even Off-Putting to Some

For many who have grown up in the years following the liturgical changes that followed the Second Vatican Council, the Traditional Latin Mass (TLM), otherwise known as the Extraordinary Form, can seem confusing, uncomfortable, and even off-putting to some. What I hope to do in a series of short columns in the bulletin is to explain the mass, step by step, so that if nothing else, our knowledge of the other half of the Roman Rite of which we are all a part, will increase. Also, it must be stated clearly that I, in no way, place the Extraordinary Form above the Ordinary or vice versa. Both forms of the Roman Rite are valid, beautiful celebrations of the liturgy and as such deserve the support and understanding of all who practice the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church. Before I begin with the actual parts of the mass, there are a few overarching details to cover. The reason the priest faces the same direction as the people when offering the mass is because he is offering the sacrifice on behalf of the congregation. He, as the shepherd, standing in persona Christi (in the person of Christ) leads the congregation towards God and towards heaven. Also, it’s important to note that a vast majority of what is said by the priest is directed towards God, not towards us. When the priest does address us, he turns around to face us. Another thing to point out is that the responses are always done by the server. If there is no server, the priest will say the responses himself. -

THE RELATIONSHIP of the LAY CAMILLIAN FAMILY with the ORDER of CAMILLIANS and the CHURCH Rome, 16 October 2018

THE RELATIONSHIP OF THE LAY CAMILLIAN FAMILY WITH THE ORDER OF CAMILLIANS AND THE CHURCH Rome, 16 October 2018 Fr. Angelo Brusco Introduction The prophecy of St. Camillus who predicted the spread throughout the world of the little plant of the Order that he had founded has also been fulfilled as regards the Lay Camillian Family (LCF). Indeed, today the LCF is present in all the continents of the world, multiplying the number of arms stretched out towards those who find themselves going through the difficult season of suffering. The pathway that has led this association to the point at which it is today is very variegated and has been conditioned by numerous factors of a socio- cultural and religious character. My paper does not have the goal of addressing in a detailed way the history of the Lay Camillian Family, which, indeed, has already been the subject of numerous articles, including mine, even though we still do not have a systematic analysis of the history of the LCF. In a necessary reference to its history, I will thus confine myself to referring solely to the events that help us to understand the relationship of this association with the Order of Camillians and the Church. The Relationship with the Order of Camillians Father Mario Vanti, the most authoritative historian of our Institute, wrote that within the Order of Camillians an ‘almost congenital’ need has been present to aggregate lay people to the exercise of its apostolic mission. This need was perceived as early as the beginnings of the Institute, as is attested to by the Bull that founded the Order, Illius qui pro gregis , which was emanated in 1591 by Gregory XIV.