Domination and the Arts of Resistance : Hidden Transcripts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voegelin's History of Political Ideas and the Problem of Christian Order

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Voegelin's History of Political Ideas and the problem of Christian order: a critical appraisal Jeffrey Charles Herndon Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Herndon, Jeffrey Charles, "Voegelin's History of Political Ideas and the problem of Christian order: a critical appraisal" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2487. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2487 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. VOEGELIN’S HISTORY OF POLITICAL IDEAS AND THE PROBLEM OF CHRISTIAN ORDER: A CRITICAL APPRAISAL A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of Political Science By Jeffrey C. Herndon B.A., Southwest Texas State University, 1989 M.A., Southwest Texas State University, 1993 May 2003 Acknowledgements Contrary to the mythology of authorship, the writing of a book is really a collective enterprise. While invariably the names of one or two people appear on the title page, my own experience leads me to believe that no book would ever be finished without the help, love, support, and some degree of gentle authoritarianism on the part of those prodding the author forward in his or her work. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Ambivalence of Resistance: West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2c73n9k4 Author Boyle, Michael Shane Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence By Michael Shane Boyle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair Professor Anton Kaes Professor Shannon Steen Fall 2012 The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence © Michael Shane Boyle All Rights Reserved, 2012 Abstract The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance After the Age of Affluence by Michael Shane Boyle Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair While much humanities scholarship focuses on the consequence of late capitalism’s cultural logic for artistic production and cultural consumption, this dissertation asks us to consider how the restructuring of capital accumulation in the postwar period similarly shaped activist practices in West Germany. From within the fields of theater and performance studies, “The Ambivalence of Resistance: West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence” approaches this question historically. It surveys the types of performance that decolonization and New Left movements in 1960s West Germany used to engage reconfigurations in the global labor process and the emergence of anti-imperialist struggles internationally, from documentary drama and happenings to direct action tactics like street blockades and building occupations. -

The Commune Movement During the 1960S and the 1970S in Britain, Denmark and The

The Commune Movement during the 1960s and the 1970s in Britain, Denmark and the United States Sangdon Lee Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2016 i The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement ⓒ 2016 The University of Leeds and Sangdon Lee The right of Sangdon Lee to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 ii Abstract The communal revival that began in the mid-1960s developed into a new mode of activism, ‘communal activism’ or the ‘commune movement’, forming its own politics, lifestyle and ideology. Communal activism spread and flourished until the mid-1970s in many parts of the world. To analyse this global phenomenon, this thesis explores the similarities and differences between the commune movements of Denmark, UK and the US. By examining the motivations for the communal revival, links with 1960s radicalism, communes’ praxis and outward-facing activities, and the crisis within the commune movement and responses to it, this thesis places communal activism within the context of wider social movements for social change. Challenging existing interpretations which have understood the communal revival as an alternative living experiment to the nuclear family, or as a smaller part of the counter-culture, this thesis argues that the commune participants created varied and new experiments for a total revolution against the prevailing social order and its dominant values and institutions, including the patriarchal family and capitalism. -

The Imaginative Tension in Henry David Thoreau's Political Thought

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Arcadian Exile: The Imaginative Tension in Henry David Thoreau’s Political Thought A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Politics School of Arts and Sciences of the Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Joshua James Bowman Washington, D.C. 2016 Arcadian Exile: The Imaginative Tension in Henry David Thoreau’s Political Thought Joshua James Bowman, Ph.D. Director: Claes G. Ryn, Ph.D. Henry David Thoreau‘s writings have achieved a unique status in the history of American literature. His ideas influenced the likes of Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., and play a significant role in American environmentalism. Despite this influence his larger political vision is often used for purposes he knew nothing about or could not have anticipated. The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze Thoreau’s work and legacy by elucidating a key tension within Thoreau's imagination. Instead of placing Thoreau in a pre-conceived category or worldview, the focus on imagination allows a more incisive reflection on moral and spiritual questions and makes possible a deeper investigation of Thoreau’s sense of reality. Drawing primarily on the work of Claes Ryn, imagination is here conceived as a form of consciousness that is creative and constitutive of our most basic sense of reality. The imagination both shapes and is shaped by will/desire and is capable of a broad and qualitatively diverse range of intuition which varies depending on one’s orientation of will. -

The State of the Arts in the Middle East

Viewpoints Special Edition The State of the Arts in the Middle East The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mei.edu Cover photos are credited, where necessary, in the body of the collection. 2 The Middle East Institute Viewpoints: The State of the Arts in the Middle East • www.mei.edu Viewpoints Special Edition The State of the Arts in the Middle East The Middle East Institute Viewpoints: The State of the Arts in the Middle East • www.mei.edu 3 Also in this series.. -

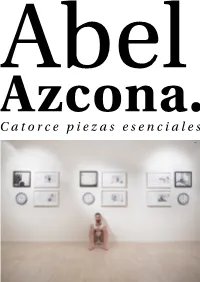

Azcona. Catorce Piezas Esenciales 1 Abel Azcona

Abel Azcona. Catorce piezas esenciales 1 Abel Azcona. Nació el 1 de abril de 1988, fruto de un embarazo no deseado, en la Clínica Montesa de Madrid, institución regentada por una congregación religiosa dirigida a personas en si- tuación de riesgo de exclusión social e indigencia. De padre desconocido, su madre, una joven en ejercicio de la prostitución y politoxicomania llamada Victoria Luján Gutierrez le abandonó en la propia maternidad a los pocos días de nacer. Las religiosas entregaron al recién nacido a un hombre vinculado a su madre, que insistió en su paternidad, a pesar de haber conocido a Victoria ya embarazada y haber sido compañero sentimental esporádico. Azcona se crio desde entonces en la ciudad de Pamplona con la familia de este, igualmente desestructurada y vinculada al narcotráfico y la delincuencia, al estar él entrando y saliendo de prisión de forma continuada. Los primeros cuatro años de vida de Azcona se contextua- lizan en situaciones continuadas de maltrato, abuso y abandono provocadas por diferentes integrantes del nuevo entorno familiar y el paso por varios domicilios, fruto de diferentes retiradas de custodia por instituciones públicas de protección social. El niño se encontraba en situación total de abandono, con signos visibles de abuso, de descuido y de desnutrición, y se aportan testimonios de vecinos y el entorno confirmando que el menor se llega a en- contrar semanas en total soledad en el domicilio, que no cumple las condiciones mínimas de habitabilidad. De los cuatro a los seis años Azcona empieza a ser acogido puntualmente por una familia conservadora navarra que, a los seis años de edad de Azcona, solicitan a instituciones pú- blicas la intervención para convertir la situación en un acogimiento familiar permanente. -

Amy | ‘Tis the Season | Meru | the Wolfpack | the Jinx | Big Men | Caring for Mom & Dad | Walt Disney | the Breach | GTFO Scene & He D

November-December 2015 VOL. 30 THE VIDEO REVIEW MAGAZINE FOR LIBRARIES NO. 6 IN THIS ISSUE Amy | ‘Tis the Season | Meru | The Wolfpack | The Jinx | Big Men | Caring for Mom & Dad | Walt Disney | The Breach | GTFO scene & he d BAKER & TAYLOR’S SPECIALIZED A/V TEAM OFFERS ALL THE PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND EXPERTISE TO FULFILL YOUR LIBRARY PATRONS’ NEEDS. Le n more about Bak & Taylor’s Scene & He d team: ELITE Helpful personnel focused exclusively on A/V products and customized services to meet continued patron demand PROFICIENT Qualified entertainment content buyers ensure frontlist and backlist titles are available and delivered on time SKILLED Supportive Sales Representatives with an average of 15 years industry experience DEVOTED Nationwide team of A/V processing staff ready to prepare your movie and music products to your shelf-ready specifications KNOWLEDGEABLE Full-time staff of A/V catalogers, backed by their MLS degree and more than 43 years of media cataloging expertise 800-775-2600 x2050 [email protected] www.baker-taylor.com Spotlight Review Amy HHH 2011, she died of alcohol toxicity at the age of Lionsgate, 128 min., R, 27. Drawing on early home movies, newsreel DVD: $19.98, Blu-ray: footage, and recorded audio interviews, Amy $24.99, Dec. 1 serves up a sorrowful portrait of an artist’s Publisher/Editor: Randy Pitman This disturbing, dis- deadly downward spiral. Extras include au- concerting, booze ‘n’ dio commentary by the director, previously Associate Editor: Jazza Williams-Wood drugs documentary unseen performances by Winehouse, and Copy Editor: Kathleen L. Florio about British song- deleted scenes. -

The Political Aesthetics of Global Protest : the Arab Spring and Beyond, P

eCommons@AKU Individual Volumes ISMC Series 2014 The olitP ical Aesthetics of Global Protest : the Arab Spring and Beyond Pnina Werbner Editor Martin Webb Editor Kathryn Spellman-Poots Editor Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_volumes Part of the African History Commons, Asian History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Werbner, P. , Webb, M. , Spellman-Poots, K. (Eds.). (2014). The Political Aesthetics of Global Protest : the Arab Spring and Beyond, p. 448. Available at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_volumes/3 The Political Aesthetics of Global Protest The Arab Spring and Beyond Edited by Pnina Werbner, Martin Webb and Kathryn Spellman-Poots in association with THE AGA KHAN UNIVERSITY (International) in the United Kingdom Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations The opinions expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Aga Khan University, Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations. © editorial matter and organisation Pnina Werbner, Martin Webb and Kathryn Spellman-Poots, 2014 © the chapters, their several authors, 2014 First published in hardback in 2014 by Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh eh8 8pj www.euppublishing.com Typeset in Goudy Oldstyle by Koinonia, Manchester and printed and bound in Spain by Novoprint A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 9334 4 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9335 1 (paperback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9350 4 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 0 7486 9351 1 (epub) The right of the contributors to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. -

Early Modern Catholic Reform and the Synod of Pistoia Shaun London Blanchard Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Eighteenth-Century Forerunners of Vatican II: Early Modern Catholic Reform and the Synod of Pistoia Shaun London Blanchard Marquette University Recommended Citation Blanchard, Shaun London, "Eighteenth-Century Forerunners of Vatican II: Early Modern Catholic Reform and the Synod of Pistoia" (2018). Dissertations (2009 -). 774. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/774 EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY FORERUNNERS OF VATICAN II: EARLY MODERN CATHOLIC REFORM AND THE SYNOD OF PISTOIA by Shaun L. Blanchard, B.A., MSt. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2018 ABSTRACT EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY FORERUNNERS OF VATICAN II: EARLY MODERN CATHOLIC REFORM AND THE SYNOD OF PISTOIA Shaun L. Blanchard Marquette University, 2018 This dissertation sheds further light on the nature of church reform and the roots of the Second Vatican Council (1962–65) through a study of eighteenth-century Catholic reformers who anticipated Vatican II. The most striking of these examples is the Synod of Pistoia (1786), the high-water mark of “late Jansenism.” Most of the reforms of the Synod were harshly condemned by Pope Pius VI in the Bull Auctorem fidei (1794), and late Jansenism was totally discredited in the increasingly ultramontane nineteenth-century Catholic Church. Nevertheless, many of the reforms implicit or explicit in the Pistoian agenda – such as an exaltation of the role of bishops, an emphasis on infallibility as a gift to the entire church, religious liberty, a simpler and more comprehensible liturgy that incorporates the vernacular, and the encouragement of lay Bible reading and Christocentric devotions – were officially promulgated at Vatican II. -

Legitimacy and Criminal Justice

LEGITIMACY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE LEGITIMACY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE International Perspectives Tom R. Tyler editor Russell Sage Foundation New York The Russell Sage Foundation The Russell Sage Foundation, one of the oldest of America’s general purpose foundations, was established in 1907 by Mrs. Margaret Olivia Sage for “the improvement of social and living conditions in the United States.” The Foundation seeks to fulfill this mandate by fostering the development and dissemination of knowledge about the country’s political, social, and economic problems. While the Foundation endeav- ors to assure the accuracy and objectivity of each book it publishes, the conclusions and interpretations in Russell Sage Foundation publications are those of the authors and not of the Foundation, its Trustees, or its staff. Publication by Russell Sage, therefore, does not imply Foundation endorsement. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Thomas D. Cook, Chair Kenneth D. Brody Jennifer L. Hochschild Cora B. Marrett Robert E. Denham Kathleen Hall Jamieson Richard H. Thaler Christopher Edley Jr. Melvin J. Konner Eric Wanner John A. Ferejohn Alan B. Krueger Mary C. Waters Larry V. Hedges Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Legitimacy and criminal justice : international perspectives / edited by Tom R. Tyler. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-87154-876-4 (alk. paper) 1. Criminal justice, Administration of. 2. Social policy. 3. Law enforcement. I. Tyler, Tom R. HV7419.L45 2008 364—dc22 2007010929 Copyright © 2007 by Russell Sage Foundation. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of Amer- ica. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

The Genealogy of Nick Land's Anti-Anthropocentric Philosophy: a Psychoanalytic Conception of Machinic Desire

The genealogy of Nick Land's anti-anthropocentric philosophy: a psychoanalytic conception of machinic desire. 1 2 The genealogy of Nick Land's anti-anthropocentric philosophy: a psychoanalytic conception of machinic desire. Stephen Overy Submitted in fulfilment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy Philosophical Studies, University of Newcastle July 2015 3 4 Abstract In recent years the philosophical texts of Nick Land have begun to attract increasing attention, yet no systematic treatment of his work exists. This thesis considers one significant and distinctive aspect of Land's work: his use of a psychoanalytic vocabulary, which is deployed to try and avoid several problems associated with metaphysical discourse. Land's larger project of responding to the Kantian settlement in philosophy is sketched in the introduction, as is his avowed distaste for thought which is conditioned by anthropocentricism. This thesis then goes on to provide a genealogical reading of the concepts which Land will borrow from psychoanalytic discourse, tracing the history of drive and desire in the major psychoanalytic thinkers of the twentieth century. Chapter one considers Freud, his model of the unconscious, and the extent to which it is anthropocentric. Chapter two contrasts Freud's materialism to Lacan's idealism. Chapter three returns to materialism, as depicted by Deleuze and Guattari in Anti-Oedipus. This chapter also goes on to consider the implications of their 'schizoanalysis', and contrasts 'left' and 'right' interpretations of Deleuze, showing how they have appropriated his work. Chapter four considers Lyotard's works from his 'libidinal period' of the late sixties to early seventies. These four readings, and the various theories of drive and desire they contain, are then contextualised in relation to Land's work in chapter five. -

Download the GA2014 E-Book for Free

XVII Generative Art Conference - GA2014 ,QWKHVWDQGWKFRYHUDQDQDPRUSKLFSHUVSHFWLYHIURPLQVLGHDEDURTXHFDWKHGUDO DQGDVHTXHQFHRIELUGVDOOJHQHUDWHGE\&HOHVWLQR6RGGX 7KH'9'LPDJHVRIJHQHUDWHGELUGVDUHXQLTXHDOOGLIIHUHQWDQGGHGLFDWHGWRHDFK SDUWLFLSDQWWR*$ 3ULQWHGLQ0LODQWKH1RYHPEHU 'RPXV$UJHQLD3XEOLVKHU ,6%1 page # 1 XVII Generative Art Conference - GA2014 *(1(5$7,9($57 *$;9,,,QWHUQDWLRQDO&RQIHUHQFH 5RPHDQG'HFHPEHU &RQIHUHQFHDW7HPSLRGL$GULDQR ([KLELWLRQDWWKH*DOOHU\RI$QJHOLFD/LEUDU\ /LYH3HUIRUPDQFHVDW&HUYDQWHV*DOOHU\ 3URFHHGLQJV (GLWHGE\&HOHVWLQR6RGGXDQG(QULFD&RODEHOOD *HQHUDWLYH'HVLJQ/DE 3ROLWHFQLFRGL0LODQR8QLYHUVLW\,WDO\ page # 2 XVII Generative Art Conference - GA2014 INDEX page # 7 *HQHUDWLYH$UW&ORXG ,QWURGXFWLRQE\&HOHVWLQR6RGGXDQG(QULFD&RODEHOOD 3DSHUV page # 10 &HOHVWLQR6RGGX ,WDO\*HQHUDWLYH'HVLJQ/DE3ROLWHFQLFRGL0LODQR8QLYHUVLW\ *HQHUDWLYH$UW*HRPHWU\/RJLFDO,QWHUSUHWDWLRQVIRU*HQHUDWLYH$OJRULWKPV page # 24 $ELU$FKDUMHH 8.8QLYHUVLW\&ROOHJH/RQGRQ )RUP*HQHUDWLRQDQG2SWLPLVHG3DQHOLQJIRU7KH2YDO page # 34 $OHMDQGUR/RSH]5LQFRQ )UDQFH&156 $UWLILFLDO'UDZLQJ page # 47 $QGUHD:ROOHQVDN%ULGJHW%DLUG 86$&RQQHFWLFXW&ROOHJH'HSDUWPHQWRI$UW 3K U DVH7UDQVLWLRQ$*HQHUDWLYHO\&RQVWUXFWHG,QWHUDFWLYH9LVXDODQG3RHWLF(QYLURQPHQW page # 57 %HQ%DUXFK%OLFK ,VUDHO+LVWRU\DQG7KHRU\GHSW%H]DOHO$FDGHP\RI$UWVDQG'HVLJQ 7ZLVWHGERGLHVDQQLKLODWLQJWKHDHVWKHWLF page # 79 %LQ8PLQR$VDNR6RJD -DSDQ7R\R8QLYHUVLW\5\XNRNX8QLYHUVLW\ $XWRPDWLF&RPSRVLWLRQ6RIWZDUHIRU7KUHH*HQUHVRI'DQFH8VLQJ'0RWLRQ'DWD page # 92 'DQLHO%LVLJ3DEOR3DODFLR 6ZLW]HUODQG6SDLQ=XULFK8QLYHUVLW\RIWKH$UWV