Case Comment BURDEN of PROOF and FALSE STATEMENTS OF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

200708 BT Ge2020 in Numbers

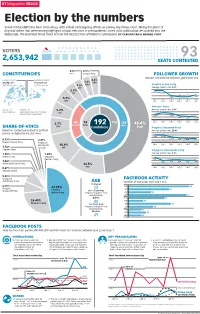

BT Infographics GE2020 Election by the numbers Social media platforms have been abuzz with virtual campaigning efforts as polling day draws close, taking the place of physical rallies that were among highlights of past elections in pre-pandemic times. With political parties pushed into the digital age, The Business Times looks at how the GE2020 has unfolded in cyberspace. BY CLAUDIA TAN & NATALIE CHOY VOTERS 93 2,653,942 SEATS CONTESTED 0.5% 0.5% CONSTITUENCIES PPP Independent FOLLOWER GROWTH Number of Facebook followers gained per day Largest GRC Smallest SMC 2.6% Ang Mo Kio Potong Pasir 2.6% SDA 185,465 electors 19,740 electors 2.6% RDU People’s Action Party SPP Average growth rate: 2.3% 3.1% 1,332 RP 1,347 338 338 653 5.2% 516 NSP July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 Workers’ Party GRCs: 17 SMCs: 14 5.2% Average growth rate: 9.5% New: Sengkang New: Kebun Baru, Yio Chu Kang, PV Marymount, Punggol West 2,699 2,098 2,421 1,474 1,271 1,336 July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 5.7% 40 74 118 152 48.4% Female New 192PSP Male SHARE-OF-VOICE SDP Candidates PAP Progress Singapore Party Based on content generated by political Average growth rate: 22.4% parties on digital media platforms 1,539 1,539 1,119 0.19% 2.29% 932 836 776 People’s Power Party Singapore Democratic 10.9% July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 1.72% Alliance WP Peoples Voice Singapore Democratic Party 1.48% 1.60% Average growth rate: 5.6% Reform Party Singapore People’s Party 813 1.46% 498 558 565 503 540 National Solidarity Party 12.5% 0.67% PSP July 1 July 2 -

Using Newspaper Reports to Glean Insight Into Current Affairs. a Case Study : the Singapore Parliamentary and Presidential Elections

Using newspaper reports to glean insight into current affairs. A Case study : The Singapore Parliamentary and Presidential Elections. NewspaperSG • Online archives of Singapore newspapers • 1831 – 2009 • URL: newspapers.nl.sg Elections in 2011 • Parliamentary Elections : 7 May 2011 • Presidential Elections : 27 August 2011 Singapore’s politics • 10 Parliamentary Elections between 1968 – 2006 • People’s Action Party (PAP) won all seats in 1968, 1972, 1976, 1980. • Opposition won 2 seats in 1984; 1 in 1988; 4 in 1991; 2 in 1997; 2 in 2001; and 2 in 2006. • 2011 : PAP lost 6 seats and garnered only 60.14% (lowest ever) of total votes casted. Presidential Elections • 1993 : Ong Teng Cheong elected • 1999 & 2005 : S R Nathan (uncontested) • 2011 candidates: – Tan Cheng Bock, Tan Jee Say, Tan Kheng Yam & Tan Kin Lian • Singaporeans politically apathetic? • Only concern about economic well-being and material wealth? • “stifling environment” • traditional media bias towards ruling party • Internet (political sites) & new media NewspaperSG usage stats in 2011 Month Unique visitors Number of visits Pages Jan 2011 35285 65453 395319 Feb 2011 36412 64109 376205 Mar 2011 49841 90780 473786 Apr 2011 42936 76677 412861 May 2011 66527 116862 611861 Jun 2011 47421 85069 522151 Jul 2011 48929 90345 517565 Aug 2011 51222 94665 523321 Sep 2011 49802 93781 509233 Oct 2011 48486 94649 506465 Nov 2011 46601 105525 495306 Dec 2011 43821 107918 490345 Total 567283 1085833 5836418 Most viewed articles in May 2011 Most viewed articles in August 2011 Top keyword -

Exclusive Frontline Interview with Dr Tan Cheng Bock

1 9 ............................. President’s Forum VOLUME 38 NO.7 J U LY 2 0 0 6 11 ........................... News from SMA Council MICA (P) 180/02/2006 13 ........................... Medical Tourism/Medical Travel (Part 2) 17 ........................... The Hobbit Speaks on Subutex 19 ........................... Tips for Creating Your Website 24 ........................... What’s Up Doc - Dr Allen Yeoh SMANEWS Exclusive Frontline Interview EDITORIAL BOARD with Dr Tan Cheng Bock Editor By Dr Toh Han Chong and Dr Tan Wu Meng Dr Toh Han Chong Deputy Editor Dr Daniel Fung Members Prof Chee Yam Cheng Dr Lee Chung Horn Dr Jeremy Lim Dr Terence Lim Dr Oh Jen Jen Dr Tan Poh Kiang Dr Tan Wu Meng Dr Teo Eng Swee Cuthbert Ex-Officio Dr Wong Chiang Yin Dr Raymond Chua Chief Administrator Ms Chua Gek Eng Editorial Manager Ms Krysania Tan Editorial Executive Ms Adeline Chua r Tan Cheng Bock obtained his medical a board member of the Land Transport Authority till degree from the then University of Singapore September 2005. The views and opinions in 1968 and went on to become a medical Besides politics, Dr Tan is also active in the expressed in all the articles D are those of the authors. practitioner. He joined the political scene in 1980 as a corporate sector, chairing Chuan Hup Holdings These are not the views Member of Parliament (MP) and has served the Ayer Limited and Dredging International Asia Pacific. of the Editorial Board nor the SMA Council unless Rajah Constituency for 25 years. In the 2001 general Though Dr Tan has since retired from the political specifically stated so in elections, Dr Tan topped the polls with a 88% win. -

Speech by Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong at the Singapore

SPEECH BY SENIOR MINISTER GOH CHOK TONG AT THE SINGAPORE SCOUT ASSOCIATION’S 100t h YEAR ANNIVERSARY DINNER AT SUNTEC INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION CENTRE ON SATURDAY, 27 FEBRUARY 2010, AT 7.30 PM Introduction 1. First, let me congratulate the Singapore Scout Association on the 100th anniversary of scouting in Singapore. This is a worthy milestone to celebrate, especially as Singapore is such a young nation. 2. Scouting was first introduced to Singapore in 1908, but only officially inaugurated two years later. Under the guidance of Scoutmaster Frank Cooper Sands who was also known as the “Father of Malayan Scouting”, the scout movement grew rapidly. From only 20 scouts 100 years ago, it has 11,000 members today, 9,000 of whom are students. Value of uniformed groups 3. Still, in my view, this is not a large number, given our current eligible student population of over 400,000. But we should not judge the impact of the scout movement by numbers but rather by the values it imparts and the leaders it has thrown up. An eminent example was the late Dr Ee Peng Liang, a former president of the Singapore Scout Association. He headed the Community Chest for many years and was known as Mr Compassion. It is also not surprising that many former scouts have held or are holding senior positions in the government and private sector. Tommy Koh and Tan Cheng Bock, both of whom are here tonight, come to mind. And it cannot just be a coincidence when both former Prime Ministers, and the present one, were all scouts. -

IPS FORUM – RESERVED PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION Mr K

1 IPS FORUM – RESERVED PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION Mr K. Shanmugam Minister for Home Affairs and Minister for Law 8 September 2017 2 OVERVIEW 1. Role of the President 2. 2016 Amendments • Eligibility Criteria • Reserved Elections 3 (1) ROLE OF THE PRESIDENT 4 ROLE OF THE PRESIDENT From 1965 From 1991 Symbolic Role Additional Custodial Role in 2 specific areas Past Key Reserves Appointments • Head of State • Unifying figure • Ceremonial duties • Traditional Westminster functions Safeguarding the Protecting the Past Reserves integrity of the Public Service 5 SYMBOLIC ROLE 6 SYMBOLIC ROLE “[The Yang di-Pertuan Negara] is not a powerful man with power of life and death over us. His role is that of constitutional Head of the State of Singapore. He is the personification of the State of which you and I are members. … Source: National Gallery He symbolises all of us. To him devotion and loyalty are due.” – Then PM Lee Kuan Yew, 3 Dec 1959, Inauguration of President Yusof Bin Ishak 7 SYMBOLIC ROLE • Our position follows the UK – • Monarch plays important role symbolizing national identity & unity • British constitutional expert, Vernon Bogdanor: “… First, there are constitutional functions, primarily formal or residual, such as appointing a Prime Minister and dissolving the legislature. Second, there are various ceremonial duties. Third, and perhaps most important, is the symbolic function, by means of which the head of state represents and symbolises not just the state but the nation. It is this last role that is the crucial one...” 8 SYMBOLIC ROLE • Hallmark of Presidential office from its inception • Prior Convention – to rotate among ethnic groups “[The] convention of rotating the Presidency among the races was important to remind Singaporeans that their country was multi-racial. -

GE2020 Results

Five-member GRCs Aljunied Ang Mo Kio East Coast Electors: 150,821; Electors: 185,261; Electors: 121,644; total votes cast: 151,007; rejected votes: 5,009 total votes cast: 178,039; rejected votes: 5,009 total votes cast: 115,630; rejected votes: 1,393 59.93% 40.07% 71.91% 28.09% 53.41% 46.59% (85,603 votes) (57,244 votes) (124,430 votes) (48,600 votes) (61,009 votes) (53,228 votes) WORKERS’ PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S REFORM PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ PARTY ACTION PARTY ACTION PARTY PARTY ACTION PARTY PARTY Pritam Singh Alex Yeo Lee Hsien Loong Kenneth Jeyaretnam Heng Swee Keat Abdul Shariff Sylvia Lim Chan Hui Yuh Darryl David Andy Zhu Cheryl Chan Dylan Ng Gerald Giam Chua Eng Leong Gan Thiam Poh Charles Yeo Jessica Tan Kenneth Foo Leon Perera Shamsul Kamar Nadia Ahmad Samdin Darren Soh Maliki Osman Nicole Seah Faisal Manap Victor Lye Ng Ling Ling Noraini Yunus Tan Kiat How Terence Tan 2015 winner: Workers’ Party (50.95%) 2015 winner: People’s Action Party (78.63%) 2015 winner: People’s Action Party (60.73%) Jurong Marine Parade Nee Soon Electors: 131,058; Electors: 139,622; Electors: 146,902; total votes cast: 125,400; rejected votes: 2,517 total votes cast: 131,630; rejected votes:1,787 total votes cast: 139,289; rejected votes: 2,199 74.62% 25.38% 57.76% 42.24% 61.90% 38.10% (91,692 votes) (31,191 votes) (74,993 votes) (54,850 votes) (86,219 votes) (53,070 votes) PEOPLE’S RED DOT PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ PEOPLE’S PROGRESS ACTION PARTY UNITED ACTION PARTY PARTY ACTION PARTY SINGAPORE PARTY Tharman Shanmugaratnam Alec Tok Tan Chuan-Jin Fadli Fawzi K Shanmugam -

The People's Action Party and the Singapore Presidency in 2017 : Understanding the Contradictions Between State Discourse and State Practice

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. The People's Action Party and the Singapore presidency in 2017 : understanding the contradictions between state discourse and state practice Mohamed Nawab Mohamed Osman; Waikar, Prashant 2019 Mohamed Nawab Mohamed Osman, & Waikar, P. (2019). The People's Action Party and the Singapore presidency in 2017 : understanding the contradictions between state discourse and state practice. Asian Survey, 59(2), 382‑405. doi:10.1525/AS.2019.59.2.382 https://hdl.handle.net/10356/142254 https://doi.org/10.1525/AS.2019.59.2.382 Mohamed Nawab Mohamed Osman, & Waikar, P. 2019. The People's Action Party and the Singapore presidency in 2017 : understanding the contradictions between state discourse and state practice. Asian Survey, 59(2), 382‑405. https://doi.org/10.1525/AS.2019.59.2.382 © 2019 by the Regents of the University of California/Sponsoring Society or Association. Downloaded on 26 Sep 2021 20:56:15 SGT MOHAMED NAWAB MOHAMED OSMAN AND PRASHANT WAIKAR The People’s Action Party and the Singapore Presidency in 2017 Understanding the Contradictions between State Discourse and State Practice Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/as/article-pdf/59/2/382/79470/as_2019_59_2_382.pdf by guest on 17 June 2020 ABSTRACT While the Singapore government has sought to construct the elected presidency as an institution critical to Singapore’s political system, the result in fact forces the insti- tution to contradict itself. This paradox has important implications for politics in a post–Lee Hsien Loong Singapore. KEYWORDS: People’s Action Party, Singapore presidential election 2017, state praxes, state discourse, post-Lee Singapore INTRODUCTION In September 2017, Singapore elected Halimah Yacob as the country’s first- ever female president. -

This Is a Pre-Print of Walid Jumblatt Abdullah (2020) “'New Normal' No

This is a pre-print of Walid Jumblatt Abdullah (2020) “‘New normal’ no more: democratic backsliding in Singapore after 2015,” Democratization. “New Normal” No More: Democratic Backsliding in Singapore After 2015 Introduction “Is there evidence of a global democratic recession? The answer is unfortunately, yes.”1 The ominous warning has spurred a significant volume of scholarship investigating democratic backsliding.2 Yet, within the field of Comparative Politics, scholars have almost exclusively focused on backsliding in democracies. Scant attention has been paid to democratic backsliding in hybrid regimes. If hybrid regimes are not static, but can move forward or backwards along the spectrum of autocracy and liberalization, then it is crucial to investigate democratic backsliding in hybrid regimes as much as their trajectories towards liberalization. Democratic backsliding in hybrid regimes, which can be defined as an extension of executive powers – formal or informal – and the constricting of political space for non-state actors, whether members of the opposition or civil society, needs to be interrogated, and its causes, understood.3 This article investigates the competitive authoritarian regime of Singapore and the quality of democracy in the city-state since the year 2011. 2011 is chosen as a starting point because it was the year in which the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) suffered its worst ever electoral performance, and subsequently, adopted a softer tone and promised an expansion of the political space. Many analysts expected the PAP to pursue a continued path of liberalization after 2011. Yet, after the subsequent GE in 2015, in which the PAP attained a much higher share of the votes in a resounding victory, there is an apparent democratic backsliding. -

Polling Scorecard

Kebun Baru SMC Yio Chu Kang SMC Sembawang GRC Marymount SMC Pulau Punggol West SMC Seletar Pasir Ris- Polling Sengkang GRC Punggol GRC Pulau Tekong Marsiling- Nee Soon Yew Tee GRC GRC Pulau Ubin Pulau Serangoon scorecard Chua Chu Kang GRC Holland- Ang Mo Kio Bukit Panjang Bukit Timah GRC SMC GRC Hong Kah Here’s your guide to the polls. Bukit North SMC Aljunied Tampines Batok GRC GRC You can ll in the results SMC as they are released tonight on Bishan-Toa East Coast Pioneer Payoh GRC GRC str.sg/GE2020-results SMC West Coast GRC Jalan Marine Tanjong Besar Parade Pagar GRC GRC GRC Hougang SMC Mountbatten SMC MacPherson SMC Pulau Brani Jurong Yuhua Jurong Potong Pasir SMC Island SMC GRC 5-member GRCs Radin Mas SMC Sentosa 4-member GRCs Single-member constituencies (SMCs) New GROUP REPRESENTATION CONSTITUENCIES Aljunied 151,007 Ang Mo Kio 185,465 Votes cast Spoilt votes voters Votes cast Spoilt votes voters WP No. of votes: PAP No. of votes: Pritam Singh, 43 Sylvia Lim, 55 Faisal Manap, 45 Gerald Giam, 42 Leon Perera, 49 Lee Hsien Loong, Gan Thiam Poh, 56 Darryl David, 49 Ng Ling Ling, 48 Nadia Samdin, 30 68 PAP No. of votes: RP No. of votes: Victor Lye, 58 Alex Yeo, 41 Shamsul Kamar, Chan Hui Yuh, 44 Chua Eng Leong, Kenneth Andy Zhu, 37 Darren Soh, 52 Noraini Yunus, 52 Charles Yeo, 30 48 49 Jeyaretnam, 61 • Aljunied GRC was won by the WP in 2011, making it the rst GE2015 result: • Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong made his 1984 electoral debut in Teck Ghee GE2015 result: opposition-held GRC. -

Press Statement by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong on Presidential Election 2011

Sep 07, 2011 16:58 +08 Press Statement by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong on Presidential Election 2011 This is the first Presidential Election in 18 years. It is good that Singaporeans have had the chance to vote for their next President, and to focus on what the elected President is about. I thank the four candidates for putting themselves forward. Voters have chosen Dr Tony Tan as our Head of State, to represent us at home and abroad, and to exercise custodial powers, including over reserves and key appointments. This was an intensely fought election, and the result was very close. Dr Tony Tan and Dr Tan Cheng Bock (who had the next highest number of votes) both conveyed strong unifying messages, and declared their intention to work closely with the Government. Both have long records of public service – Dr Tony Tan in many roles in Government, and Dr Tan Cheng Bock as a highly respected backbench MP. It is reassuring that Singaporean voters recognised and valued their strengths, as well as their inclusive approach. Voters faced a difficult choice between Dr Tony Tan and Dr Tan Cheng Bock. This explains why the winning margin is so narrow, and why the winner only gained slightly more than one-third of the total votes. Nevertheless, under our first-past-the-post system, the election has produced an unambiguous winner, who has the mandate to be the next President. I have called Dr Tony Tan to congratulate him on his election, and assure him of my Government’s full cooperation. I also called Dr Tan Cheng Bock to thank him and his supporters for having fought an effective and dignified campaign. -

Round up Reply by Minister for Defence Teo Chee Hean in Parliament

Round Up Reply by Minister for Defence Teo Chee Hean in Parliament 20 Jan 2006 Mr Deputy Speaker, Sir, first of all, let me thank Members of the House for sharing their views and comments on this very important issue of National Service. Sir, I am heartened to hear Members of the House expressing their very strong support for National Service and to hear that their support is shared by their constituents. Indeed, it is such support for National Service and the commitment shown by our NSmen that make our nation's defence work. As I said, 700,000 Singaporeans have served National Service or are serving National Service and, without their commitment, we will not have the modern thriving Singapore that we have today. Sir, let me address now some of the specific issues that Members have raised. Alternative forms of National Service The need for flexibility Considering the talents and contributions of NS defaulters Post-graduate studies Pre-enlistees with special talents Citizens who left at a young age Permanent Residents' liability for National Service Alternative punishment for defaulters Conclusion As I have explained earlier, National Service has served a critical need and that is, in my view, the first principle of National Service. Firstly, criticality, secondly, universality, and thirdly, equity. That critical need is national defence and we should not be trading that off against other forms of service, whether it is in the social sector, in the arts or in sports, because they do not rank in the same way as that necessity for national defence. -

News from SMA Council by Dr Yue Wai Mun, Honorary Secretary

12 Council News News from SMA Council By Dr Yue Wai Mun, Honorary Secretary 1. ADVERTISEMENT ON “HAIR LOSS IN MEN” (STRAITS TIMES, 9 SEP 2001) The Health Sciences Authority (HSA) is very concerned and is closely monitoring the current trend of “non-product specific” advertisements appearing in the newspapers and other media. Although these “non-product specific” advertisements make no mention of any particular brand of products and do not seem to fall under the definition of product advertisement and promotion under the Medicines Act, HSA will look into the matter further and take appropriate follow-up action. 2. CONGRATULATIONS The 42nd SMA Council extends its congratulations and best wishes to the following SMA Members: a. New Appointments in the Ministries i. A/Prof Vivian Balakrishnan, Minister of State, Ministry of National Development (wef 1 Jan 2002) *Dr Balakrishnan is also an SMA Council Member. ii. Dr Sadasivan Balaji, Minister of State, Ministry of Health and Ministry of Environment iii. Dr Ng Eng Hen, Minister of State, Ministry of Education and Ministry of Manpower (wef 1 Jan 2002) b. General Election 2001 i. Dr Ong Seh Hong (Aljunied) ii. Dr Sadasivan Balaji (Ang Mo Kio) iii. Dr Tan Cheng Bock (Ayer Rajah) iv. Dr Ng Eng Hen (Bishan-Toa Payoh) v. A/Prof Vivian Balakrishnan (Holland-Bukit Panjang) vi. Dr Lily Tirtasana Neo (Jalan Besar) vii. Dr Warren Lee (Sembawang) c. Singapore Medical Council Election 2001 i. A/Prof Ho Nai Kiong (until 5 Nov 2004) ii. Dr Tan Kok Soo (until 5 Nov 2004) iii.Dr Richard Guan (until 18 May 2002) 3.