This Is a Pre-Print of Walid Jumblatt Abdullah (2020) “'New Normal' No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Votes and Proceedings No. 69

VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWELFTH PARLIAMENT OF SINGAPORE First Session WEDNESDAY, 5 MARCH 2014 No. 69 12 noon 509 PRESENT: Mdm SPEAKER (Mdm HALIMAH YACOB (Jurong)). Mr ANG HIN KEE (Ang Mo Kio). Mr ANG WEI NENG (Jurong). Mr BAEY YAM KENG (Tampines). Mr CHAN CHUN SING (Tanjong Pagar), Minister for Social and Family Development and Second Minister for Defence. Mr CHEN SHOW MAO (Aljunied). Mrs LINA CHIAM (Non-Constituency Member). Mr CHARLES CHONG (Joo Chiat), Deputy Speaker. Mr CHRISTOPHER DE SOUZA (Holland-Bukit Timah). Ms FAIZAH JAMAL (Nominated Member). Mr NICHOLAS FANG (Nominated Member). Mr ARTHUR FONG (West Coast). Mr CEDRIC FOO CHEE KENG (Pioneer). Ms FOO MEE HAR (West Coast). Ms GRACE FU HAI YIEN (Yuhua), Minister, Prime Minister's Office, Second Minister for the Environment and Water Resources and Second Minister for Foreign Affairs. Mr GAN KIM YONG (Chua Chu Kang), Minister for Health and Government Whip. Mr GAN THIAM POH (Pasir Ris-Punggol). Mr GERALD GIAM YEAN SONG (Non-Constituency Member). No. 69 5 MARCH 2014 510 Mr GOH CHOK TONG (Marine Parade). Mr HAWAZI DAIPI (Sembawang), Senior Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Education and Acting Minister for Manpower. Mr HENG CHEE HOW (Whampoa), Senior Minister of State, Prime Minister's Office and Deputy Leader of the House. Mr HENG SWEE KEAT (Tampines), Minister for Education. Mr HRI KUMAR NAIR (Bishan-Toa Payoh). Mr INDERJIT SINGH (Ang Mo Kio). Ms INDRANEE RAJAH (Tanjong Pagar), Senior Minister of State, Ministry of Law and Ministry of Education. Dr INTAN AZURA MOKHTAR (Ang Mo Kio). Mr S ISWARAN (West Coast), Minister, Prime Minister's Office, Second Minister for Home Affairs and Second Minister for Trade and Industry. -

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan Abstract In Singapore, the percentage of elected female politicians rose from 3.8 percent in 1984 to 22.5 percent after the 2015 general election. After years of exclusion, why were gender reforms adopted and how did they lead to more women in political office? Unlike South Korea and Taiwan, this paper shows that in Singapore party pragmatism rather than international diffusion of gender equality norms, feminist lobbying, or rival party pressures drove gender reforms. It is argued that the ruling People’s Action Party’s (PAP) strategic and electoral calculations to maintain hegemonic rule drove its policy u-turn to nominate an average of about 17.6 percent female candidates in the last three elections. Similar to the PAP’s bid to capture women voters in the 1959 elections, it had to alter its patriarchal, conservative image to appeal to the younger, progressive electorate in the 2000s. Additionally, Singapore’s electoral system that includes multi-member constituencies based on plurality party bloc vote rule also makes it easier to include women and diversify the party slate. But despite the strategic and electoral incentives, a gender gap remains. Drawing from a range of public opinion data, this paper explains why traditional gender stereotypes, biased social norms, and unequal family responsibilities may hold women back from full political participation. Keywords: gender reforms, party pragmatism, plurality party bloc vote, multi-member constituencies, ethnic quotas, PAP, Singapore DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5509/2016892369 ____________________ Netina Tan is an assistant professor of political science at McMaster University. -

The Rule of Law and Urban Development

The Rule of Law and Urban Development The transformation of Singapore from a struggling, poor country into one of the most affluent nations in the world—within a single generation—has often been touted as an “economic miracle”. The vision and pragmatism shown by its leaders has been key, as has its STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS notable political stability. What has been less celebrated, however, while being no less critical to Singapore’s urban development, is the country’s application of the rule of law. The rule of law has been fundamental to Singapore’s success. The Rule of Law and Urban Development gives an overview of the role played by the rule of law in Singapore’s urban development over the past 54 years since independence. It covers the key principles that characterise Singapore’s application of the rule of law, and reveals deep insights from several of the country’s eminent urban pioneers, leaders and experts. It also looks at what ongoing and future The Rule of Law and Urban Development The Rule of Law developments may mean for the rule of law in Singapore. The Rule of Law “ Singapore is a nation which is based wholly on the Rule of Law. It is clear and practical laws and the effective observance and enforcement and Urban Development of these laws which provide the foundation for our economic and social development. It is the certainty which an environment based on the Rule of Law generates which gives our people, as well as many MNCs and other foreign investors, the confidence to invest in our physical, industrial as well as social infrastructure. -

1 Moving Fast, Far and Forward by Edwin Tong, SC, Senior Minister Of

Moving Fast, Far and Forward By Edwin Tong, SC, Senior Minister of State for Law and Health Wefie with MinLaw officers at COS 2019 The budget season is upon us again. Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Finance Heng Swee Keat just delivered his Budget Statement in Parliament on 18 February. It was a budget that addresses immediate concerns, yet is also far- sighted. We have to respond to challenges in the new decade, against a backdrop of COVID-19 outbreak, as well as global structural shifts, economic uncertainties and strategic tensions, and yet also ask what kind of Singapore we want to have in the decades to come. From tomorrow till next week, the Parliament will sit as a Committee of Supply, and examine the various ministries’ plans. This rigorous process is necessary to ensure that the budget addresses Singapore’s current and future needs, while remaining fiscally sustainable – a sacrosanct principle which has served us well. Before the Ministry of Law (MinLaw) presents our plans for the year to the Committee of Supply, I thought I would share what we had achieved last year. We Moved FAST Singapore is a small country, with small population and land area. As our Founding Father Mr Lee Kuan Yew said, “for Singapore to survive and prosper, we need to be relevant and useful to the world”. To maintain relevance, we need to be nimble and adapt to the constantly changing world. The same applies to our legal industry. We are small, with only about 1,000 law firms and 7,000 lawyers; the world’s largest law firm has more lawyers than all of Singapore! To carve out a niche for 1 ourselves in the world, we need to adapt, and adapt fast, to the evolving legal landscape – shifting client expectations, alternative legal service providers, legal technology. -

4 Comparative Law and Constitutional Interpretation in Singapore: Insights from Constitutional Theory 114 ARUN K THIRUVENGADAM

Evolution of a Revolution Between 1965 and 2005, changes to Singapore’s Constitution were so tremendous as to amount to a revolution. These developments are comprehensively discussed and critically examined for the first time in this edited volume. With its momentous secession from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, Singapore had the perfect opportunity to craft a popularly-endorsed constitution. Instead, it retained the 1958 State Constitution and augmented it with provisions from the Malaysian Federal Constitution. The decision in favour of stability and gradual change belied the revolutionary changes to Singapore’s Constitution over the next 40 years, transforming its erstwhile Westminster-style constitution into something quite unique. The Government’s overriding concern with ensuring stability, public order, Asian values and communitarian politics, are not without their setbacks or critics. This collection strives to enrich our understanding of the historical antecedents of the current Constitution and offers a timely retrospective assessment of how history, politics and economics have shaped the Constitution. It is the first collaborative effort by a group of Singapore constitutional law scholars and will be of interest to students and academics from a range of disciplines, including comparative constitutional law, political science, government and Asian studies. Dr Li-ann Thio is Professor of Law at the National University of Singapore where she teaches public international law, constitutional law and human rights law. She is a Nominated Member of Parliament (11th Session). Dr Kevin YL Tan is Director of Equilibrium Consulting Pte Ltd and Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore where he teaches public law and media law. -

200708 BT Ge2020 in Numbers

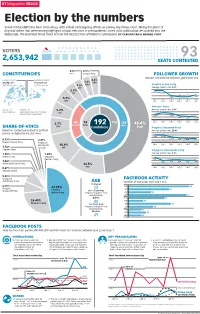

BT Infographics GE2020 Election by the numbers Social media platforms have been abuzz with virtual campaigning efforts as polling day draws close, taking the place of physical rallies that were among highlights of past elections in pre-pandemic times. With political parties pushed into the digital age, The Business Times looks at how the GE2020 has unfolded in cyberspace. BY CLAUDIA TAN & NATALIE CHOY VOTERS 93 2,653,942 SEATS CONTESTED 0.5% 0.5% CONSTITUENCIES PPP Independent FOLLOWER GROWTH Number of Facebook followers gained per day Largest GRC Smallest SMC 2.6% Ang Mo Kio Potong Pasir 2.6% SDA 185,465 electors 19,740 electors 2.6% RDU People’s Action Party SPP Average growth rate: 2.3% 3.1% 1,332 RP 1,347 338 338 653 5.2% 516 NSP July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 Workers’ Party GRCs: 17 SMCs: 14 5.2% Average growth rate: 9.5% New: Sengkang New: Kebun Baru, Yio Chu Kang, PV Marymount, Punggol West 2,699 2,098 2,421 1,474 1,271 1,336 July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 5.7% 40 74 118 152 48.4% Female New 192PSP Male SHARE-OF-VOICE SDP Candidates PAP Progress Singapore Party Based on content generated by political Average growth rate: 22.4% parties on digital media platforms 1,539 1,539 1,119 0.19% 2.29% 932 836 776 People’s Power Party Singapore Democratic 10.9% July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 1.72% Alliance WP Peoples Voice Singapore Democratic Party 1.48% 1.60% Average growth rate: 5.6% Reform Party Singapore People’s Party 813 1.46% 498 558 565 503 540 National Solidarity Party 12.5% 0.67% PSP July 1 July 2 -

Using Newspaper Reports to Glean Insight Into Current Affairs. a Case Study : the Singapore Parliamentary and Presidential Elections

Using newspaper reports to glean insight into current affairs. A Case study : The Singapore Parliamentary and Presidential Elections. NewspaperSG • Online archives of Singapore newspapers • 1831 – 2009 • URL: newspapers.nl.sg Elections in 2011 • Parliamentary Elections : 7 May 2011 • Presidential Elections : 27 August 2011 Singapore’s politics • 10 Parliamentary Elections between 1968 – 2006 • People’s Action Party (PAP) won all seats in 1968, 1972, 1976, 1980. • Opposition won 2 seats in 1984; 1 in 1988; 4 in 1991; 2 in 1997; 2 in 2001; and 2 in 2006. • 2011 : PAP lost 6 seats and garnered only 60.14% (lowest ever) of total votes casted. Presidential Elections • 1993 : Ong Teng Cheong elected • 1999 & 2005 : S R Nathan (uncontested) • 2011 candidates: – Tan Cheng Bock, Tan Jee Say, Tan Kheng Yam & Tan Kin Lian • Singaporeans politically apathetic? • Only concern about economic well-being and material wealth? • “stifling environment” • traditional media bias towards ruling party • Internet (political sites) & new media NewspaperSG usage stats in 2011 Month Unique visitors Number of visits Pages Jan 2011 35285 65453 395319 Feb 2011 36412 64109 376205 Mar 2011 49841 90780 473786 Apr 2011 42936 76677 412861 May 2011 66527 116862 611861 Jun 2011 47421 85069 522151 Jul 2011 48929 90345 517565 Aug 2011 51222 94665 523321 Sep 2011 49802 93781 509233 Oct 2011 48486 94649 506465 Nov 2011 46601 105525 495306 Dec 2011 43821 107918 490345 Total 567283 1085833 5836418 Most viewed articles in May 2011 Most viewed articles in August 2011 Top keyword -

One Party Dominance Survival: the Case of Singapore and Taiwan

One Party Dominance Survival: The Case of Singapore and Taiwan DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lan Hu Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor R. William Liddle Professor Jeremy Wallace Professor Marcus Kurtz Copyrighted by Lan Hu 2011 Abstract Can a one-party-dominant authoritarian regime survive in a modernized society? Why is it that some survive while others fail? Singapore and Taiwan provide comparable cases to partially explain this puzzle. Both countries share many similar cultural and developmental backgrounds. One-party dominance in Taiwan failed in the 1980s when Taiwan became modern. But in Singapore, the one-party regime survived the opposition’s challenges in the 1960s and has remained stable since then. There are few comparative studies of these two countries. Through empirical studies of the two cases, I conclude that regime structure, i.e., clientelistic versus professional structure, affects the chances of authoritarian survival after the society becomes modern. This conclusion is derived from a two-country comparative study. Further research is necessary to test if the same conclusion can be applied to other cases. This research contributes to the understanding of one-party-dominant regimes in modernizing societies. ii Dedication Dedicated to the Lord, Jesus Christ. “Counsel and sound judgment are mine; I have insight, I have power. By Me kings reign and rulers issue decrees that are just; by Me princes govern, and nobles—all who rule on earth.” Proverbs 8:14-16 iii Acknowledgments I thank my committee members Professor R. -

The Candidates

BT INFOGRAPHICS GE2015 The candidates Bukit Batok Sengkang West SMC SMC Sembawang Punggol East GRC SMC Hougang Marsiling- SMC Yew Tee GRC Nee Soon GRC Chua Chu Kang AngAng Mo MoKio Kio Holland- Pasir Ris- GRC GRCGRC Bukit Punggol GRC Timah Hong Kah GRC North SMC Tampines Bishan- Aljunied GRC Toa Payoh GRC East Coast GRC Jurong GRC GRC West Coast GRC Marine Parade Tanjong Pagar GRC GRC Fengshan SMC FOUR-MEMBER GRC Jalan Besar Chua Chu Kang MacPherson SMC GRC (Estimated no. of electors: 119,848) Mountbatten SMC PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY POWER PARTY Gan Kim Yong Goh Meng Seng Low Yen Ling Lee Tze Shih Pioneer Yuhua Bukit Panjang Radin Mas Potong Yee Chia Hsing Low Wai Choo SMC SMC SMC SMC Pasir SMC Zaqy Mohamad Syafarin Sarif East Coast SIX-MEMBER GRC FIVE-MEMBER GRC FOUR-MEMBER GRC SINGLE-MEMBER CONSTITUENCY (SMC) (Estimated no. electors: 99,015) PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ SIX-MEMBER GRC FIVE-MEMBER GRC ACTION PARTY PARTY Jessica Tan Daniel Goh Ang Mo Kio Aljunied Nee Soon Lee Yi Shyan Gerald Giam (Estimated no. of electors: 187,652) (Estimated no. of electors: 148,024) (Estimated no. of electors: 132,200) Lim Swee Say Leon Perera Maliki Bin Osman Fairoz Shariff PEOPLE’S THE REFORM WORKERS’ PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ Holland-Bukit Timah ACTION PARTY PARTY PARTY ACTION PARTY ACTION PARTY PARTY (Estimated no. of electors: 104,397) Ang Hin Kee Gilbert Goh Chen Show Mao Chua Eng Leong Henry Kwek Cheryl Denise Loh Darryl David Jesse Loo Low Thia Kiang K Muralidharan Pillai K Shanmugam Gurmit Singh Gan Thiam Poh M Ravi Faisal Abdul Manap Shamsul Kamar Lee Bee Wah Kenneth Foo Intan Azura Mokhtar Osman Sulaiman Pritam Singh Victor Lye Louis Ng Luke Koh PEOPLE’S SINGAPORE ACTION PARTY DEMOCRATIC PARTY Koh Poh Koon Roy Ngerng Sylvia Lim Yeo Guat Kwang Faishal Ibrahim Ron Tan Christopher De Souza Chee Soon Juan Lee Hsien Loong Siva Chandran Liang Eng Hwa Chong Wai Fung Bishan-Toa Payoh Sembawang Sim Ann Paul Ananth Tambyah Pasir Ris-Punggol (Estimated no. -

Wee Chiaw Sek Anna V Ng Li-Ann Genevieve

Wee Chiaw Sek Anna v Ng Li-Ann Genevieve (sole executrix of the estate of Ng Hock Seng, deceased) and another [2013] SGCA 36 Case Number : Civil Appeal No 140 of 2012 Decision Date : 28 June 2013 Tribunal/Court : Court of Appeal Coram : Chao Hick Tin JA; Andrew Phang Boon Leong JA; Tan Lee Meng J Counsel Name(s) : Hri Kumar Nair SC and Tan Sze Mei Angeline (Drew & Napier LLC) for the appellant; Deborah Barker SC and Ushan Premaratne (KhattarWong LLP) for the first respondent Edwin Tong, Tham Hsu Hsien, Nakul Dewan and Peh Aik Hin (Allen & Gledhill LLP) for the second respondent. Parties : Wee Chiaw Sek Anna — Ng Li-Ann Genevieve (sole executrix of the estate of Ng Hock Seng, deceased) and another Contract – Misrepresentation – Fraudulent Contract – Misrepresentation – Exaggeration Family Law – Matrimonial Assets – Division Restitution – Unjust Enrichment Trusts – Constructive Trusts – Remedial Constructive Trusts [LawNet Editorial Note: This was an appeal from the decision of the High Court in [2012] SGHC 197.] 28 June 2013 Judgment reserved. Andrew Phang Boon Leong JA (delivering the judgment of the court): Introduction 1 This is an appeal against the trial judge’s (“the Judge”) decision in Wee Chiaw Sek Anna v Ng Li- Ann Genevieve (sole executrix of the estate of Ng Hock Seng, deceased) and another [2012] SGHC 197 (“the Judgment”). 2 The threshold issue is whether the Appellant’s ex-husband, Mr Ng Hock Seng (“the Deceased”), who died in 2004, had fraudulently misrepresented to the Appellant that he had little or no assets, thus inducing her to forgo division of matrimonial assets at ancillary proceedings. -

70Th Anniversary Pooja Chathayam 2018 Charity Transparency Award

ISSUE 01. 2019 70th Anniversary Pooja Charity Transparency Award 2018 On 18 June 2018, Sree Narayana Mission (SNM) SNM won the Charity Transparency Award 2018 celebrated its 70th year anniversary. A special for the first time, a testament to its high standards of Guru Pooja attended by SNM members was corporate governance and transparency. SNM is one held at the Mission, followed by a cake-cutting of 47 charities to win this award, among the over 2000 ceremony and a vegetarian dinner. This event was the first in a series of celebrations to mark registered charities in Singapore. SNM will continue to SNM’s 70th anniversary. meet the highest levels of governance and will work towards attaining the next tier of corporate governance awards, the Charity Governance Award. Chathayam 2018 As a show of solidarity with the victims of the August 2018 Kerala flood crisis, SNM scaled down its Chathayam celebrations to mark the Guru’s 164th Birth Anniversary. It held a Chathayam Observance on Sunday, 2 Sep 2018. The Saturday Cultural Programme was cancelled and Senior Minister of State Edwin Tong was invited as Guest-of-Honour, and Minister Ong Ye Kung as Special Guest. Members of the Inter-Religious Organisation Singapore were also invited to conduct a special joint prayer for the flood victims. SNM also partnered with the Singapore Red Cross to raise $14,000.00 for the relief effort. MOU with Cycling Without Age Trained volunteers from SNM, CWA, and various other grassroots organisations will hop into specially designed e-trishaws which will take the elderly residents of SNMNH on scenic rides around the Nee Soon and Sembawang neighbourhoods. -

View Brochure

th ANNIVERSARY Artist Impression of the School of Law. CONTENTS e First Decade e Founding Years e Future 2 LAW OF SCHOOL 3 LAW OF SCHOOL e idea of the “We were audacious aer “Aer sending in the proposal, I told SMU Law School receiving encouragement – we my colleagues in the Law Department was in the minds were cautioned to take it slowly we had a 50-50 chance of getting a law of the SMU and open the school a few years school. e arguments for it – diversity, later than when we actually did. competition and SMU’s development – leadership from We took a risk but being young were compelling enough, but whether the university’s and impatient, we discarded the proposal would be accepted inception. caution and brought forward depended on the powers that be. When our vision by a few years. In the the good news came, we were elated! end, we pulled it o and the Law It was a great privilege to have been School has been acknowledged involved in the start-up of the SMU Law as one of the nest in Asia since School - a memory I will always cherish.” then. e moral? Carpe diem … seize the day!” Associate Professor Low Kee Yang, School of Law Mr Ho Kwon Ping, Chairman, Board of Trustees, SMU “A Law School was in the original plan of SMU. It’s a natural discipline that ts in well with the original concept of a management university.” Professor Tan Chin Tiong, Senior Advisor to President, SMU 5 LAW OF SCHOOL “I remember receiving a call, as president, in early 2007 saying that the opening of a new “It was vital for the School to law school at SMU had been oer a distinct law education approved.