The People's Action Party and the Singapore Presidency in 2017 : Understanding the Contradictions Between State Discourse and State Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opening Remarks by Senior Minister Teo Chee Hean at the Public Sector Data Security Review Committee Press Conference on 27 November 2019

OPENING REMARKS BY SENIOR MINISTER TEO CHEE HEAN AT THE PUBLIC SECTOR DATA SECURITY REVIEW COMMITTEE PRESS CONFERENCE ON 27 NOVEMBER 2019 Good morning everyone and thank you for attending the press conference. Work of the PSDSRC 2 As you know, in 2018 and 2019, we uncovered a number of data-related incidents in the public sector. In response to these incidents, the government had immediately introduced additional IT security measures. Some of these measures included network traffic and database activity monitoring, and endpoint detection and response for all critical information infrastructure. But, there was a need for a more comprehensive look at public sector data security. 3 On 31 March this year, the Prime Minister directed that I chair a Committee to conduct a comprehensive review of data security policies and practices across the public sector. 4 I therefore convened a Committee, which consisted of my colleagues from government - Dr Vivian Balakrishnan, Mr S Iswaran, Mr Chan Chun Sing, and Dr Janil Puthucheary - as well as five international and private sector representatives with expertise in data security and technology. If I may just provide the background of these five private sector members: We have Professor Anthony Finkelstein, Chief Scientific Adviser for National Security to the UK Government and an expert in the area of data and cyber security; We have Mr David Gledhill who is with us today. He is the former Chief Information Officer of DBS and has a lot of experience in applying these measures in the financial and banking sector; We have Mr Ho Wah Lee, a former KPMG partner with 30 years of experience in information security, auditing and related issues across a whole range of entities in the private and public sector; We have Mr Lee Fook Sun, who is the Executive Chairman of Ensign Infosecurity. -

ASA 36/07/94 Distr: UA/SC UA 256/94

EXTERNAL (for general distribution) AI Index: ASA 36/07/94 Distr: UA/SC UA 256/94 Death Penalty 4 July 1994 SINGAPORE Jasbir SINGH, aged 30 Charanjit SINGH, age not known On 14 February 1994 the Court of Criminal Appeal rejected the appeal of Jasbir Singh and Charanjit Singh against their sentence of death for trafficking in 254.36 grams of diamorphine. Jasbir and Charanjit were arrested on 24 May 1988 on charges of drug trafficking. Jasbir had been staying at the flat of an acquaintance who was away on holiday. There he found a bag of powder and was arrested while trying to determine the nature of this powder. Jasbir had asked his friend Charanjit to accompany him. Both were tried and sentenced to death on 5 January 1993. They will now file an appeal for clemency with the President of Singapore, Ong Teng Cheong. BACKGROUND INFORMATION The death penalty was employed during the colonial period and was retained after Singapore became an independent republic in August 1965. Anyone found in possession of more than 15 grams of heroin, 30 grams of morphine, 30 grams of cocaine or 500 grams of cannabis is presumed guilty of drug trafficking and is liable to a mandatory death sentence. Amnesty International opposes the death penalty in all cases as a violation of the right to life and the right not to be subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, as proclaimed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. RECOMMENDED ACTION: Please send telegrams/telexes/faxes/express and airmail letters either in English or in your own language: - expressing concern at the imposition of the death sentence on Jasbir Singh and Charanjit Singh; - stating Amnesty International's unconditional opposition to the death penalty. -

Country Report Singapore

Country Report Singapore Natural Disaster Risk Assessment and Area Business Continuity Plan Formulation for Industrial Agglomerated Areas in the ASEAN Region March 2015 AHA CENTRE Japan International Cooperation Agency OYO International Corporation Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. Overview of the Country Basic Information of Singapore 1), 2), 3) National Flag Country Name Long form : Republic of Singapore Short form : Singapore Capital Singapore (city-state) Area (km2) Total: 716 Land: 700 Inland Water: 16 Population 5,399,200 Population density(people/ km2 of land area) 7,713 Population growth (annual %) 1.6 Urban population (% of total) 100 Languages Malay (National/Official language), English, Chinese, Tamil (Official languages) Ethnic Groups Chinese 74%, Malay 13%, Indian 9%, Others 3% Religions Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, Daoism, Hinduism GDP (current US$) (billion) 298 GNI per capita, PPP (current international $) 76,850 GDP growth (annual %) 3.9 Agriculture, value added (% of GDP) +0 Industry, value added (% of GDP) 25 Services, etc., value added (% of GDP) 75 Brief Description Singapore is a city-state consisting of Singapore Island, which is located close to the southern edge of the Malay Peninsula, and 62 other smaller outlying islands. Singapore is ranked as the second most densely populated country in the world, after Monaco. With four languages being used as official languages, the country itself is a competitive business district. Therefore, there are many residents other than Singaporean living in the country. Singapore is one of the founding members of ASEAN (founded on August 8, 1967), and the leading economy in ASEAN. Cooperation with ASEAN countries is a basic diplomatic policy of Singapore. -

Full Version of Cv

Adrian David Cheok AM Phone: +61423977539 or +60128791271 19A Robe Terrace Email: [email protected] Medindie, 5081 Homepage: https://www.adriancheok.info Australia https://www.imagineeringinstitute.org Personal Date of Birth: December 18, 1971. Place of birth: Adelaide, Australia Australian Citizen. Summary of Career Adrian David Cheok AM is Director of the Imagineering Institute, Malaysia, Full Professor at i-University Tokyo, Visiting Professor at Raffles University, Malaysia, Visiting Professor at University of Novi Sad-Serbia, on Technical faculty \Mihailo Pupin", Serbia, Faculty of Ducere Business School, and CEO of Nikola Tesla Technologies Corporation. He is Founder and Director of the Mixed Reality Lab, Singapore. He was formerly Professor of Pervasive Computing, University of London, Full Professor and Executive Dean at Keio University, Graduate School of Media Design and Associate Professor in the National University of Singapore. He has previously worked in real-time systems, soft computing, and embedded computing in Mitsubishi Electric Research Labs, Japan. In 2019, The Governor General of Australia, Representative of Her Majesty the Queen Elizabeth II, has awarded Australia's highest honour the Order of Australia to Adrian David Cheok for his contribution to international education and research. He has been working on research covering mixed reality, human-computer interfaces, wearable computers and ubiquitous computing, fuzzy systems, embedded systems, power electronics. He has successfully obtained approximately $130 million dollars in funding for externally funded projects in the area of wearable computers and mixed reality from Daiwa Foundation, Khazanah National (Malaysian Government), Media Development Authority, Nike, National Oilwell Varco, Defence Science Technology Agency, Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Communications and Arts, National Arts Council, Singapore Sci- ence Center, and Hougang Primary School. -

© 1998 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies Was Established As an Autonomous Organization in 1968

© 1998 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies was established as an autonomous organization in 1968. It is a regional research centre for scholars and other specialists concerned with modern Southeast Asia, particularly the many-faceted problems of stability and security, economic development, and political and social change. The Institute’s research programmes are the Regional Economic Studies (RES, including ASEAN and APEC), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS), and the ASEAN Transitional Economies Programme (ATEP). The Institute is governed by a twenty-two-member Board of Trustees comprising nominees from the Singapore Government, the National University of Singapore, the various Chambers of Commerce, and professional and civic organizations. A ten-man Executive Committee oversees day-to-day operations; it is chaired by the Director, the Institute’s chief academic and administrative officer. SOUTHEAST ASIAN AFFAIRS 1998 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Chairperson Chia Siow Yue Editors Derek da Cunha John Funston Associate Editor Tan Kim Keow © 1998 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore INSTITUTE OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES © 1998 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore Cataloguing in Publication Data Southeast Asian affairs. 1974– Annual 1. Asia, Southeastern. I. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. DS501 S72A ISSN 0377-5437 ISBN 981-3055-81-2 (softcover) ISBN 981-230-009-0 (hardcover) Published by Institute of Southeast Asian Studies 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Pasir Panjang Singapore 119614 Internet e-mail: [email protected] WWW: http://merlion.iseas.edu.sg/pub.html All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior consent of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. -

Institutionalized Leadership: Resilient Hegemonic Party Autocracy in Singapore

Institutionalized Leadership: Resilient Hegemonic Party Autocracy in Singapore By Netina Tan PhD Candidate Political Science Department University of British Columbia Paper prepared for presentation at CPSA Conference, 28 May 2009 Ottawa, Ontario Work- in-progress, please do not cite without author’s permission. All comments welcomed, please contact author at [email protected] Abstract In the age of democracy, the resilience of Singapore’s hegemonic party autocracy is puzzling. The People’s Action Party (PAP) has defied the “third wave”, withstood economic crises and ruled uninterrupted for more than five decades. Will the PAP remain a deviant case and survive the passing of its founding leader, Lee Kuan Yew? Building on an emerging scholarship on electoral authoritarianism and the concept of institutionalization, this paper argues that the resilience of hegemonic party autocracy depends more on institutions than coercion, charisma or ideological commitment. Institutionalized parties in electoral autocracies have a greater chance of survival, just like those in electoral democracies. With an institutionalized leadership succession system to ensure self-renewal and elite cohesion, this paper contends that PAP will continue to rule Singapore in the post-Lee era. 2 “All parties must institutionalize to a certain extent in order to survive” Angelo Panebianco (1988, 54) Introduction In the age of democracy, the resilience of Singapore’s hegemonic party regime1 is puzzling (Haas 1999). A small island with less than 4.6 million population, Singapore is the wealthiest non-oil producing country in the world that is not a democracy.2 Despite its affluence and ideal socio- economic prerequisites for democracy, the country has been under the rule of one party, the People’s Action Party (PAP) for the last five decades. -

A Special Issue to Commemorate Singapore Bicentennial 2019

2019 A Special Issue to Commemorate Singapore Bicentennial 2019 About the Culture Academy Singapore Te Culture Academy Singapore was established in 2015 by the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth to groom the next generation of cultural leaders in the public sector. Guided by its vision to be a centre of excellence for the development of culture professionals and administrators, the Culture Academy Singapore’s work spans three areas: Education and Capability Development, Research and Scholarship and Tought Leadership. Te Culture Academy Singapore also provides professional development workshops, public lectures and publishes research articles through its journal, Cultural Connections, to nurture thought leaders in Singapore’s cultural scene. One of the Academy’s popular oferings is its annual thought leadership conference which provides a common space for cultural leaders to gather and exchange ideas and best practices, and to incubate new ideas. It also ofers networking opportunities and platforms for collaborative ideas-sharing. Cultural Connections is a journal published annually by the Culture Academy Singapore to nurture thought leadership in cultural work in the public sector. Te views expressed in the publication are solely those of the authors and contributors, and do not in any way represent the views of the National Heritage Board or the Singapore Government. Editor-in-Chief: Tangamma Karthigesu Editor: Tan Chui Hua Editorial Assistants: Geraldine Soh & Nur Hummairah Design: Fable Printer: Chew Wah Press Distributed by the Culture Academy Singapore Published in July 2019 by Culture Academy Singapore, 61 Stamford Road #02-08 Stamford Court Singapore 178892 © 2019 National Heritage Board. All rights reserved. National Heritage Board shall not be held liable for any damages, disputes, loss, injury or inconvenience arising in connection with the contents of this publication. -

Health and Medical Research in Singapore Observatory on Health Research Systems

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Europe View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation documented briefing series. RAND documented briefings are based on research briefed to a client, sponsor, or targeted au- dience and provide additional information -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)“ . If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in “sectioning" the material. It is customary tc begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from “ photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Votes and Proceedings of the Twelfth Parliament of Singapore

VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWELFTH PARLIAMENT OF SINGAPORE First Session MONDAY, 13 MAY 2013 No. 54 1.30 pm 386 PRESENT: Mdm SPEAKER (Mdm HALIMAH YACOB (Jurong)). Mr ANG WEI NENG (Jurong). Mr BAEY YAM KENG (Tampines). Mr CHAN CHUN SING (Tanjong Pagar), Acting Minister for Social and Family Development and Senior Minister of State, Ministry of Defence. Mr CHEN SHOW MAO (Aljunied). Dr CHIA SHI-LU (Tanjong Pagar). Mrs LINA CHIAM (Non-Constituency Member). Mr CHARLES CHONG (Joo Chiat), Deputy Speaker. Mr CHRISTOPHER DE SOUZA (Holland-Bukit Timah). Ms FAIZAH JAMAL (Nominated Member). Mr NICHOLAS FANG (Nominated Member). Mr ARTHUR FONG (West Coast). Mr CEDRIC FOO CHEE KENG (Pioneer). Ms FOO MEE HAR (West Coast). Ms GRACE FU HAI YIEN (Yuhua), Minister, Prime Minister's Office, Second Minister for the Environment and Water Resources and Second Minister for Foreign Affairs. Mr GAN KIM YONG (Chua Chu Kang), Minister for Health and Government Whip. Mr GAN THIAM POH (Pasir Ris-Punggol). Mr GERALD GIAM YEAN SONG (Non-Constituency Member). Mr GOH CHOK TONG (Marine Parade). No. 54 13 MAY 2013 387 Mr HAWAZI DAIPI (Sembawang), Senior Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Education and Acting Minister for Manpower. Mr HENG CHEE HOW (Whampoa), Senior Minister of State, Prime Minister's Office and Deputy Leader of the House. Mr HRI KUMAR NAIR (Bishan-Toa Payoh). Ms INDRANEE RAJAH (Tanjong Pagar), Senior Minister of State, Ministry of Law and Ministry of Education. Dr INTAN AZURA MOKHTAR (Ang Mo Kio). Mr S ISWARAN (West Coast), Minister, Prime Minister's Office, Second Minister for Home Affairs and Second Minister for Trade and Industry. -

Singapore 2017 International Religious Freedom Report

SINGAPORE 2017 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution, laws, and policies provide for religious freedom, subject to restrictions relating to public order, public health, and morality. The government continued to ban Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification (Unification Church). The government restricted speech or actions it perceived as detrimental to “religious harmony.” There is no legal provision for conscientious objection, including on religious grounds, and Jehovah’s Witnesses reported 12 conscientious objectors remained detained at year’s end. In April an Indian imam who uttered an Arabic prayer during which he asked for “help against Jews and Christians” was fined and deported for acts “prejudicial to the maintenance of religious harmony and likely to disturb public tranquility.” Three foreign Islamic preachers were banned from entering the country in October and November, and two foreign Christian speakers were banned from preaching in September because the government reportedly viewed their teaching as damaging to social harmony. The government changed a voluntary program into a mandatory requirement that all Muslim religious teachers and centers of learning register with the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (MUIS). Parliament discussed the existing prohibition on wearing the hijab for certain civil servants, but the prohibition remained. In September former Parliamentary Speaker Halimah Yacob, who wears the hijab, became president. The post was reserved in this presidential cycle for eligible Malays, who are mostly Muslim. The government made multiple high-level affirmations of the importance of religious harmony, launched an initiative to foster understanding of different religious practices, and created a fund and documentary to explore religious differences and prejudices. -

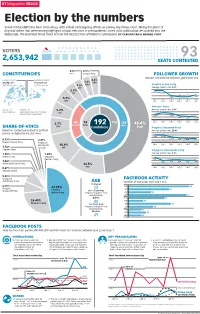

200708 BT Ge2020 in Numbers

BT Infographics GE2020 Election by the numbers Social media platforms have been abuzz with virtual campaigning efforts as polling day draws close, taking the place of physical rallies that were among highlights of past elections in pre-pandemic times. With political parties pushed into the digital age, The Business Times looks at how the GE2020 has unfolded in cyberspace. BY CLAUDIA TAN & NATALIE CHOY VOTERS 93 2,653,942 SEATS CONTESTED 0.5% 0.5% CONSTITUENCIES PPP Independent FOLLOWER GROWTH Number of Facebook followers gained per day Largest GRC Smallest SMC 2.6% Ang Mo Kio Potong Pasir 2.6% SDA 185,465 electors 19,740 electors 2.6% RDU People’s Action Party SPP Average growth rate: 2.3% 3.1% 1,332 RP 1,347 338 338 653 5.2% 516 NSP July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 Workers’ Party GRCs: 17 SMCs: 14 5.2% Average growth rate: 9.5% New: Sengkang New: Kebun Baru, Yio Chu Kang, PV Marymount, Punggol West 2,699 2,098 2,421 1,474 1,271 1,336 July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 5.7% 40 74 118 152 48.4% Female New 192PSP Male SHARE-OF-VOICE SDP Candidates PAP Progress Singapore Party Based on content generated by political Average growth rate: 22.4% parties on digital media platforms 1,539 1,539 1,119 0.19% 2.29% 932 836 776 People’s Power Party Singapore Democratic 10.9% July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 1.72% Alliance WP Peoples Voice Singapore Democratic Party 1.48% 1.60% Average growth rate: 5.6% Reform Party Singapore People’s Party 813 1.46% 498 558 565 503 540 National Solidarity Party 12.5% 0.67% PSP July 1 July 2