Elite Cohesion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

200708 BT Ge2020 in Numbers

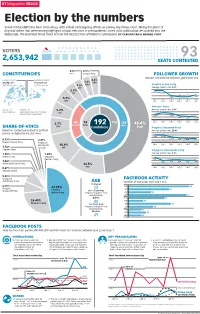

BT Infographics GE2020 Election by the numbers Social media platforms have been abuzz with virtual campaigning efforts as polling day draws close, taking the place of physical rallies that were among highlights of past elections in pre-pandemic times. With political parties pushed into the digital age, The Business Times looks at how the GE2020 has unfolded in cyberspace. BY CLAUDIA TAN & NATALIE CHOY VOTERS 93 2,653,942 SEATS CONTESTED 0.5% 0.5% CONSTITUENCIES PPP Independent FOLLOWER GROWTH Number of Facebook followers gained per day Largest GRC Smallest SMC 2.6% Ang Mo Kio Potong Pasir 2.6% SDA 185,465 electors 19,740 electors 2.6% RDU People’s Action Party SPP Average growth rate: 2.3% 3.1% 1,332 RP 1,347 338 338 653 5.2% 516 NSP July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 Workers’ Party GRCs: 17 SMCs: 14 5.2% Average growth rate: 9.5% New: Sengkang New: Kebun Baru, Yio Chu Kang, PV Marymount, Punggol West 2,699 2,098 2,421 1,474 1,271 1,336 July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 5.7% 40 74 118 152 48.4% Female New 192PSP Male SHARE-OF-VOICE SDP Candidates PAP Progress Singapore Party Based on content generated by political Average growth rate: 22.4% parties on digital media platforms 1,539 1,539 1,119 0.19% 2.29% 932 836 776 People’s Power Party Singapore Democratic 10.9% July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 1.72% Alliance WP Peoples Voice Singapore Democratic Party 1.48% 1.60% Average growth rate: 5.6% Reform Party Singapore People’s Party 813 1.46% 498 558 565 503 540 National Solidarity Party 12.5% 0.67% PSP July 1 July 2 -

170702Mindmap Copy

Who said what Numerous allegations have been made in the ongoing feud between Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and his siblings, from misuse of power to a conict Against Lee Hsien Loong of interest in preparing the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s last will. Insight charts the Against Teo Chee Hean • Allegation: PM Lee misused his claims and accusations in the dispute over the fate of 38, Oxley Road. • Allegation: Committee focused power to prevent the house from solely on challenging validity of being demolished demolition clause in Mr Lee’s will PM’s response: Denied the DPM Teo’s response: Not true that “baseless” allegations, will refute committee bent on preventing them in a ministerial statement in demolition of the house Parliament tomorrow • Allegation: Committee did not • Allegation: PM Lee made disclose options in prior exchanges, contradictory statements about only identied members and its their father’s wishes and the house terms of reference when “forced in public and private into the daylight” Ms Indranee Rajah’s DPM Teo’s response: Nothing response: Notes that secret about committee; it is like Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s numerous other committees last will specically Cabinet sets up to consider specic accepts and Against Ho Ching Against K. Shanmugam issues acknowledges that DPM Tharman Allegation: Has a pervasive Allegation: Conict of interest demolition may not take place. • • Shanmugaratnam’s inuence on government, well being on ministerial committee, response: Cabinet has beyond her job scope having advised the late Mr Lee and • Allegation: Did not challenge the numerous committees family about the house last will in court when probate was on whole range of granted • Allegation: Removed the late Mr Mr Shanmugam’s response: issues, to help think Lee’s items from house without PM’s response: Wanted to avoid a Calls the claim ridiculous; says through difcult choices approval; represented the Prime public ght that would tarnish the nothing he said precluded him from Minister’s Ofce despite not family name serving in committee. -

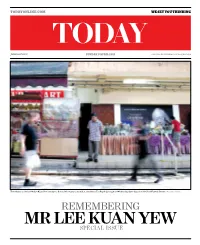

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did. -

Using Newspaper Reports to Glean Insight Into Current Affairs. a Case Study : the Singapore Parliamentary and Presidential Elections

Using newspaper reports to glean insight into current affairs. A Case study : The Singapore Parliamentary and Presidential Elections. NewspaperSG • Online archives of Singapore newspapers • 1831 – 2009 • URL: newspapers.nl.sg Elections in 2011 • Parliamentary Elections : 7 May 2011 • Presidential Elections : 27 August 2011 Singapore’s politics • 10 Parliamentary Elections between 1968 – 2006 • People’s Action Party (PAP) won all seats in 1968, 1972, 1976, 1980. • Opposition won 2 seats in 1984; 1 in 1988; 4 in 1991; 2 in 1997; 2 in 2001; and 2 in 2006. • 2011 : PAP lost 6 seats and garnered only 60.14% (lowest ever) of total votes casted. Presidential Elections • 1993 : Ong Teng Cheong elected • 1999 & 2005 : S R Nathan (uncontested) • 2011 candidates: – Tan Cheng Bock, Tan Jee Say, Tan Kheng Yam & Tan Kin Lian • Singaporeans politically apathetic? • Only concern about economic well-being and material wealth? • “stifling environment” • traditional media bias towards ruling party • Internet (political sites) & new media NewspaperSG usage stats in 2011 Month Unique visitors Number of visits Pages Jan 2011 35285 65453 395319 Feb 2011 36412 64109 376205 Mar 2011 49841 90780 473786 Apr 2011 42936 76677 412861 May 2011 66527 116862 611861 Jun 2011 47421 85069 522151 Jul 2011 48929 90345 517565 Aug 2011 51222 94665 523321 Sep 2011 49802 93781 509233 Oct 2011 48486 94649 506465 Nov 2011 46601 105525 495306 Dec 2011 43821 107918 490345 Total 567283 1085833 5836418 Most viewed articles in May 2011 Most viewed articles in August 2011 Top keyword -

Benjamin Henry Sheares, MD, MS, FRCOG

Benjamin Henry Sheares—J Sheares 25C Benjamin Henry Sheares, MD, MS, FRCOG: President, Republic of Singapore 1971-1981; Obstetrician and Gynaecologist 1931-1981 A Biography, 12th August 1907-12th May 1981 1 JHH Sheares, MA, FRCSE, FAMS Abstract From humble origins Benjamin H Sheares with self-discipline and a commitment to excel became an eminent obstetrician and gynaecologist. Beginning in 1942 under difficult conditions he pioneered many improvements in the management of obstetrical and gynaecological patients, and also improved the services and facilities at Kandang Kerbau Hospital so that maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity were markedly reduced. In January 1951 he became the first Singaporean to be appointed Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in the university, and achieved reknown in his service to patients, the teaching of undergraduates and postgraduates, and in clinical research. His surgical treatment of vaginal agenesis was acknowledged interna- tionally. He was elected President of the Republic of Singapore on 30th December 1970 by Parliament and during his three terms spanning one decade he discharged his duties with thoroughness, distinction, tolerance and a quiet dignity. When he died on 12th May 1981 85,000 people, identifying with his humble origins and his achievements through self-reliance and meritocracy, paid their last respects to him. He had set an example on how to live and depart this life. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2005;34:25C-41C Key words: Benjamin H Sheares, Biography, Development of O & G, President Singapore, Sheares operation “… let us not deny the population of Malaya (and the labour room and as it changes from a specialty Singapore) a reasonable obstetric service. -

The Candidates

BT INFOGRAPHICS GE2015 The candidates Bukit Batok Sengkang West SMC SMC Sembawang Punggol East GRC SMC Hougang Marsiling- SMC Yew Tee GRC Nee Soon GRC Chua Chu Kang AngAng Mo MoKio Kio Holland- Pasir Ris- GRC GRCGRC Bukit Punggol GRC Timah Hong Kah GRC North SMC Tampines Bishan- Aljunied GRC Toa Payoh GRC East Coast GRC Jurong GRC GRC West Coast GRC Marine Parade Tanjong Pagar GRC GRC Fengshan SMC FOUR-MEMBER GRC Jalan Besar Chua Chu Kang MacPherson SMC GRC (Estimated no. of electors: 119,848) Mountbatten SMC PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY POWER PARTY Gan Kim Yong Goh Meng Seng Low Yen Ling Lee Tze Shih Pioneer Yuhua Bukit Panjang Radin Mas Potong Yee Chia Hsing Low Wai Choo SMC SMC SMC SMC Pasir SMC Zaqy Mohamad Syafarin Sarif East Coast SIX-MEMBER GRC FIVE-MEMBER GRC FOUR-MEMBER GRC SINGLE-MEMBER CONSTITUENCY (SMC) (Estimated no. electors: 99,015) PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ SIX-MEMBER GRC FIVE-MEMBER GRC ACTION PARTY PARTY Jessica Tan Daniel Goh Ang Mo Kio Aljunied Nee Soon Lee Yi Shyan Gerald Giam (Estimated no. of electors: 187,652) (Estimated no. of electors: 148,024) (Estimated no. of electors: 132,200) Lim Swee Say Leon Perera Maliki Bin Osman Fairoz Shariff PEOPLE’S THE REFORM WORKERS’ PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ Holland-Bukit Timah ACTION PARTY PARTY PARTY ACTION PARTY ACTION PARTY PARTY (Estimated no. of electors: 104,397) Ang Hin Kee Gilbert Goh Chen Show Mao Chua Eng Leong Henry Kwek Cheryl Denise Loh Darryl David Jesse Loo Low Thia Kiang K Muralidharan Pillai K Shanmugam Gurmit Singh Gan Thiam Poh M Ravi Faisal Abdul Manap Shamsul Kamar Lee Bee Wah Kenneth Foo Intan Azura Mokhtar Osman Sulaiman Pritam Singh Victor Lye Louis Ng Luke Koh PEOPLE’S SINGAPORE ACTION PARTY DEMOCRATIC PARTY Koh Poh Koon Roy Ngerng Sylvia Lim Yeo Guat Kwang Faishal Ibrahim Ron Tan Christopher De Souza Chee Soon Juan Lee Hsien Loong Siva Chandran Liang Eng Hwa Chong Wai Fung Bishan-Toa Payoh Sembawang Sim Ann Paul Ananth Tambyah Pasir Ris-Punggol (Estimated no. -

A Sentiment Analysis of Singapore Presidential Election 2011 Using Twitter Data with Census Correction

A sentiment analysis of Singapore Presidential Election 2011 using Twitter data with census correction Murphy Choy1 Michelle L.F. Cheong2 Ma Nang Laik3 Koo Ping Shung4 Abstract Sentiment analysis is a new area in text analytics where it focuses on the analysis and understanding of the emotions from the text patterns. This new form of analysis has been widely adopted in customer relation management especially in the context of complaint management. With increasing level of interest in this technology, more and more companies are adopting it and using it to champion their marketing efforts. However, sentiment analysis using twitter has remained extremely difficult to manage due to the sampling bias. In this paper, we will discuss about the application of using reweighting techniques in conjunction with online sentiment divisions to predict the vote percentage that individual candidate will receive. There will be in depth discussion about the various aspects using sentiment analysis to predict outcomes as well as the potential pitfalls in the estimation due to the anonymous nature of the internet. Introduction Social media has been widely adopted by many private enterprises to market their products as well as services. With the successful campaign of President Obama in the US presidential campaign 2008, social media platforms such as facebook, twitter as well as other sites have catapulted to great success as the leading platform to engage voters. Many political analysts (Stirland, 2008; Pasek, 2006; Xenos, 2007) have attributed his success to the active use of social media to engage voters especially the younger voters whose concerns are usually ignored or given less importance (Pasek, 2006). -

Report of the Ministerial Committee on 38 Oxley Road

REPORT OF THE MINISTERIAL COMMITTEE ON 38 OXLEY ROAD TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Background Chapter 2: Historical and heritage significance Chapter 3: Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s thinking and wishes on the property Chapter 4: Possible options for the property Chapter 5: Committee’s views 2 CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND 1. Founding Prime Minister Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s former home at 38 Oxley Road (henceforth referred to as the “Property”) is a single-storey bungalow surrounded by low-rise residential developments. 2. The issue of whether to preserve Mr Lee’s home after his passing, to demolish it, or some other option has become a matter of public interest. Shortly after Mr Lee’s passing on 23 March 2015, PM Lee Hsien Loong addressed this issue in Parliament on 13 April 2015, where he said that “there is no immediate issue of demolition of the house, and no need for the Government to make any decision now”, given that Dr Lee Wei Ling “intended to continue living in the Property”. He also stated that “if and when Dr Lee Wei Ling no longer lives in the House, Mr Lee has stated his wishes as to what then should be done…however, it will be up to the Government of the day to consider the matter”. 3. Though there is no immediate need for a decision, given the significant public interest in the Property, the Cabinet 1 approved setting up a Ministerial Committee (“Committee”) on 1 June 2016 to consider the various options. The Committee was asked to prepare drawer plans of various options and their implications, with the benefit of views of those who had directly discussed the matter with Mr Lee, so that a future Government can refer to these plans and make a considered and informed decision when the time came to decide on the matter. -

PRIME MINISTER's PRESS CONFERENCE HELD on 26TH AUGUST, 1965, at CITY HALL. Press : (Local) Why Have You Been So Silent Over T

1 PRIME MINISTER’S PRESS CONFERENCE HELD ON 26TH AUGUST, 1965, AT CITY HALL. Press : (local) Why have you been so silent over the last few weeks? Prime Minister: First, there was a tremendous amount of work to be done. This is a radically different situation and, you know, my colleagues and I -- we like to calculate the consequence of each and every move and overture that we make or that is being made to us. And there are times when silence is golden. And you can take it from me that what Mr. Rajaratnam, the Foreign Minister, and Mr. Lim Kim San, the Finance Minister, have been saying, is said after the closest consultation with me and my colleagues. He speaks for us all... So, it does not mean that because I do not speak, we are not thinking or working. I am meeting you today because I had to meet the Chambers of Commerce and the Trade Unions, the Manufacturer's Association, because economics is the basis of successful lky\1965\lky0826.doc 2 democracy and also because I think we have cleared the hump. You know what Africans thinks about bases and the British bases. You know my position is on that. And although I am not a stranger to President Nasser, it took about two weeks for him to accord recognition, knowing full well what my position is. All of Asia now, except for Indonesia, has recognised us and I think so will the O.A.U. (The Orgainsation for African Unity). All the member-states, will, I think, recognise us. -

The Role of the Internet in Singapore's 2011 Elections

series A Buzz in Cyberspace, But No Net-Revolution The Role of the Internet in Singapore’s 2011 Elections By Kai Portmann 2011 © 2011 Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Published by fesmedia Asia Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Hiroshimastrasse 28 10874 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49-30-26935-7403 Email: [email protected] All rights reserved. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Friedrich-Ebert- Stiftung or fesmedia Asia. fesmedia Asia does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. ISBN: 978-99916-864-9-3 fesmedia Asia fesmedia Asia is the media project of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) in Asia. We are working towards a political, legal and regulatory framework for the media which follows international Human Rights law and other international or regional standards as regards to Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom. FES in Asia The Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung has been working in Asia for more than 40 years. With offices in 13 Asian countries, FES is supporting the process of self-determination democratisation and social development in cooperation with local partners in politics and society. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung The Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung is a non-governmental and non-profit making Political Foundation based in almost 90 countries throughout the world. Established in 1925, it carries the name of Germany’s first democratically elected president, Friedrich Ebert, and, continuing his legacy, promotes freedom, solidarity and social democracy. A Buzz in Cyberspace, But No Net-Revolution The Role of the Internet in Singapore’s 2011 Elections By Kai Portmann 2011 Content ABSTRACT 5 1. -

Transparency and Authoritarian Rule in Southeast Asia

TRANSPARENCY AND AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA The 1997–98 Asian economic crisis raised serious questions for the remaining authoritarian regimes in Southeast Asia, not least the hitherto outstanding economic success stories of Singapore and Malaysia. Could leaders presiding over economies so heavily dependent on international capital investment ignore the new mantra among multilateral financial institutions about the virtues of ‘transparency’? Was it really a universal functional requirement for economic recovery and advancement? Wasn’t the free flow of ideas and information an anathema to authoritarian rule? In Transparency and Authoritarian Rule in Southeast Asia Garry Rodan rejects the notion that the economic crisis was further evidence that ulti- mately capitalism can only develop within liberal social and political insti- tutions, and that new technology necessarily undermines authoritarian control. Instead, he argues that in Singapore and Malaysia external pres- sures for transparency reform were, and are, in many respects, being met without serious compromise to authoritarian rule or the sanctioning of media freedom. This book analyses the different content, sources and significance of varying pressures for transparency reform, ranging from corporate dis- closures to media liberalisation. It will be of equal interest to media analysts and readers keen to understand the implications of good governance debates and reforms for democratisation. For Asianists this book offers sharp insights into the process of change – political, social and economic – since the Asian crisis. Garry Rodan is Director of the Asia Research Centre, Murdoch University, Australia. ROUTLEDGECURZON/CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES Edited by Kevin Hewison and Vivienne Wee 1 LABOUR, POLITICS AND THE STATE IN INDUSTRIALIZING THAILAND Andrew Brown 2 ASIAN REGIONAL GOVERNANCE: CRISIS AND CHANGE Edited by Kanishka Jayasuriya 3 REORGANISING POWER IN INDONESIA The politics of oligarchy in an age of markets Richard Robison and Vedi R. -

S R Nathan 1924 - 2016 Our Brother-In-Arms, Workers’ Keeper , People’S Leader

Special Edition 23 AUGUST 2016 MCI (P) 028/12/2015 Our Brother-in-Arms, Workers’ Keeper, People’s Leader Remembering S R Nathan 1924 - 2016 Our Brother-in-arms, Workers’ Keeper , People’s Leader S R NATHAN 1924 – 2016 “My heart is with the Labour Movement and all that it stands for. It is in the Labour Movement that I grew and experienced the many injustices around us in the early years. As the saying goes, it is in the Labour Movement that we ‘small men and women’ earn our spurs and grow. It is in this movement that we learnt many of the realities of working life and overcame problems in our employment. All that remains so, even to this day.” Quote by Mr S R Nathan at the NTUC Industrial and Services Sectors and Membership Seminar at the Orchid Country Club on 19 July 2005. The Labour Movement and the Working People of Singapore will remember Mr S R Nathan’s contributions and honour his legacy for many generations to come. NTUC-Affiliated Unions and Associations • Air Transport Executive Staff Union • Amalgamated Union of Public Daily Rated Workers • Amalgamated Union of Public Employees • Amalgamated Union of Statutory Board Employees • Attractions, Resorts & Entertainment Union • Building Construction And Timber Industries Employees’ Union • Chemical Industries Employees’ Union • Creative Media and Publishing Union • DBS Staff Union • dnata Singapore Staff Union • Education Services Union • ExxonMobil Singapore Employees Union • Food, Drinks and Allied Workers Union • Healthcare Services Employees’ Union • Housing and Development Board